Narrative Art was the reality television of the Victorian era. While the artistic elite rejected it, the public loved it. Accessible and sensational it transported viewers into the scenes shown and let them identify with the characters depicted.

This art tells us much about the Victorian Age, what people feared and desired, their dark secrets and prejudices as well as their hopes and dreams. ‘Telling Tales’ explores Victorian attitudes to life and death, love and loss, animals and childhood, war and empire and the struggles of women in a man's world.

Guest curated by author and art historian Kirsty Stonell Walker, this exhibition is a collaboration with Southampton City Art Gallery, featuring masterpieces from both collections.

Love and Loss

For the Victorians there was no sweeter story than that of love. For women, marriage and children were the ultimate aim, even though childbirth brought its own dangers. Stories of love denied, or the natural order shockingly broken were equally as popular, if only to see the transgressors, usually women, get their just desserts. The risk of seduction and desertion would ruin a reputation. The risk of a bad marriage meant no escape as divorce was unthinkable for the majority.

For those blissfully in love, the spectre of separation by death made the love all the sweeter. In an era marked by the mourning of the Queen for Albert, the Victorians remained obsessed with love and death, in the certainty that one could never stop the other.

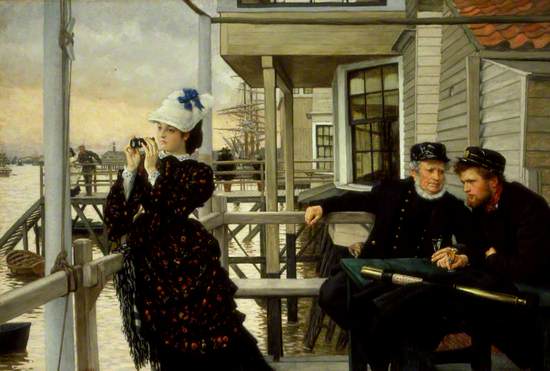

The Captain's Daughter (The Last Evening)

A young man with a very sour expression listens to the Captain’s verdict on his prospects in love. The men plan her life for her while the Captain’s daughter gazes through her telescope, unconcerned by matters of the heart as she has other things in her sights.

Despite the young suitor’s state of the art telescope, decorated with the newly invented International Code of marine signals, the Captain’s Daughter has her own opera glasses, her own vision and her own ideas of how her life will go. Her journey into her own future is blocked by the white pillar of the balcony and she is visually trapped with the men. Is she wilful and strong enough to make her own way?

James Tissot (1836–1902)

Oil on canvas

H 72.4 x W 104.8 cm

Southampton City Art Gallery

Tea in the Conservatory (Near Neighbours)

Three friends gather in a conservatory, sharing tea and gossip. However pleasant the scene, there is something amiss with the woman on the right. Her dropped gloves suggest that she has been discarded. Possibly she has suffered a heartbreak and is being comforted by her neighbours. The surrounding pots of chrysanthemums mean ‘a heart left to desolation’, indicating the romantic distress.

You might wonder if the neighbour in the middle has found a piece on her friend’s lost love in the newspaper she is reading. Has he died or married someone else? At least she has loyal friends to comfort her.

Henry 'Harry' Edward John Browne (1859–1917)

Oil on canvas

H 92 x W 122.5 cm

Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum

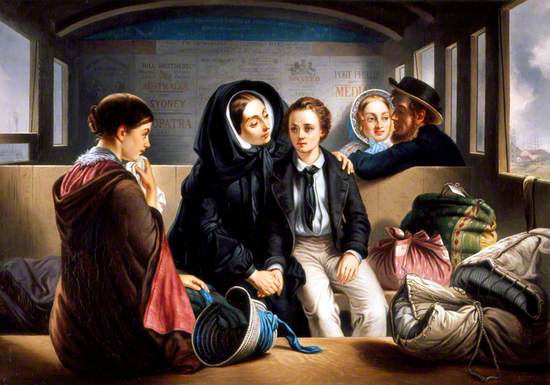

Second Class, the Parting

The subtitle of the painting is Thus Part We: Rich in Sorrow, Parting Poor. A widowed mother is bidding farewell to her son in the spartan surroundings of a second-class railway carriage. The pale, weeping daughter and the mother’s dignity, together with the halo effect of the mother’s bonnet suggests this is a once-wealthy family impoverished by bereavement.

The only decoration in the carriage are posters offering opportunities in Australia. Out of the window, boats in a harbour suggest that this young man is seeking his fortune in the Australian goldrush of 1851, but his fearful expression and youth make it an uncertain opportunity. A ruddy faced sailor looks sympathetically on, possibly recognising his own parting, many years ago.

Abraham Solomon (1823–1862)

Oil on canvas

H 54.5 x W 76.3 cm

Southampton City Art Gallery

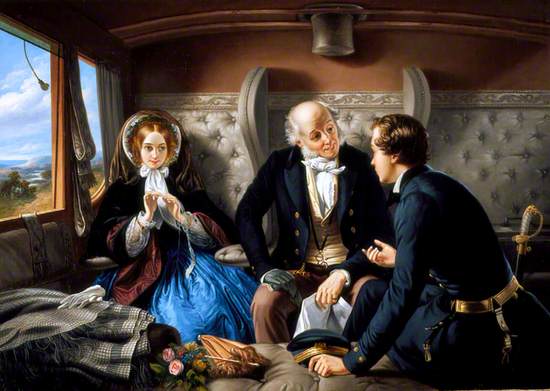

First Class, the Meeting

By contrast to its companion piece, First Class, the Meeting is a far more luxurious scene. The seats are padded, with privacy wings. The windows have tassels and curtains, with a looped tapestry cord and are almost as finely decorated as the privileged travellers who are comfortably seated within.

The subtitle for First Class, the Meeting was ‘And at First Meeting Loved’, emphasising the elegant space as a location for courtship within the appropriate social sphere. The wealthy and handsome young naval officer engages a father in conversation while the daughter demurely gazes on. Her bag reveals pink roses symbolising her gentle, sweet love which she waits for this handsome stranger to reciprocate.

Abraham Solomon (1823–1862)

Oil on canvas

H 54.5 x W 76.3 cm

Southampton City Art Gallery

Love Locked Out

After Anna Lea Merritt’s husband died soon after they were married, she painted a monumental tribute to their lost love in 1889. The sad figure of Cupid is barred from the tomb, with nature dying all around, neglected. This image of being unable to be with the one you loved resonated with the public, especially after Oscar Wilde’s (1854-1900) trial in 1895. It remained popular into the twentieth century, with the title ‘Love Locked Out’ being used for newspaper headlines, a comedy play and even a piece of jazz music.

The popularity of the painting made Sir Merton Russell-Cotes seek out a copy for his collection, which he obtained from Henry Justice Ford, a popular artist and illustrator.

Henry Justice Ford (1860–1941)

Oil on canvas

H 109 x W 58 cm

Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum

Beasts and Babies

The Victorian love of dogs culminated in Charles Cruft’s first dog show in 1891. In art, dogs were used to display very human emotions and to make statements about society. Likewise, for the Victorians, children in art represented complex themes. Thanks to improvements in medicine, the spectre of childhood mortality had receded for some, and there was an expectation that children would grow to be adults. In art, sweet girls foreshadowed their transition into wives and mothers, and little boys forged ahead as leaders and providers. There were inevitably the bad apples, children who teased and bullied who were destined to be a problem to society.

Tick-Tick

An inquisitive pug puppy has made her way into a cupboard and has discovered a pocket watch. Its ticking is of great interest, and she seems to be watching the time tick on. Is she waiting for the return of her master or for her dinner? Is she just waiting to grow up?

Pugs were extremely with the Victorians, as they are today. Queen Victoria had a small herd of pugs among her many dogs, and all had the short noses that Rivière’s has, which has sadly been lost through overbreeding. One of England’s most popular and well-regarded animal painters, Rivière insisted “you can never paint a dog unless you are fond of it”, so this little puppy had endeared herself to the artist before she became a popular engraving.

Briton Riviere (1840–1920)

Oil on canvas

H 36.5 x W 48 cm

Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum

Her First Love

A girl cradles her docile rabbit, absolutely besotted. She looks out towards the viewer inviting us to admire her pet. Is the painter suggesting that in time, this pretty girl is destined to become someone’s doted pet as well?

The title comes from James Sheridan Knowles’ (1784-1862) comic play The Love Chase (1800) - ‘Her first love is her last!’ It could be that the girl will never love anyone as much as she loves her rabbit and will in fact never love again. This is a rather bleak outlook for the girl’s future – if she is not destined to be a wife and mother, then what will become of her? Even worse, she may marry but will not love her husband, remaining a decorative pet for others to admire.

George Sheridan Knowles (1863–1931)

Oil on canvas

H 81.5 x W 62.5 cm

Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum

Always Welcome

The scene is in a 17th century Dutch interior and a little girl is paying a visit to her mother who is in bed, unwell. Beside the bed, lies open a Bible. The outcome seems uncertain as the mother seems to fade into the darkness of her curtained bed. However, she holds tightly to her tiny daughter’s hand, who seems to pull her from the darkness. The daughter’s clothing seems very grown up, like a costume, possibly hinting that the little girl might have to grow up quickly if her mother dies.

Laura Alma-Tadema was the second wife of Dutch painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912), and the stepmother to his two daughters, writer Laurence and artist Anna. She had a passion for 17th century Dutch art, which was often reflected in her art.

Laura Theresa Epps Alma-Tadema (1852–1909)

Oil on canvas

H 37 x W 54 cm

Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum

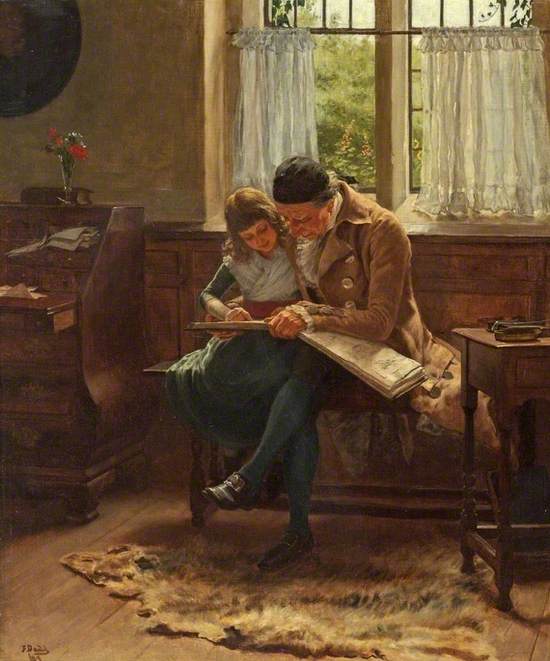

The Scrap Book

A little girl sits beside an older man, possibly her grandfather, on a window seat and looks at his scrapbook. The fur rug at their feet suggests that the grandfather has had a few adventures to tell, which is why his granddaughter is so enthralled, but possibly he is encouraging her to go on her own adventures. In the bright garden outside the window are some fox-gloves, a plant which to the Victorians symbolised ‘I am ambitious for you, not for myself’ suggesting the grandfather’s stories are meant to inspire.

Frank Dadd (1851–1929)

Oil on canvas

H 60 x W 50 cm

Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum

Gods and Generals

One thing an Englishman knew for certain in the Victorian era was that God was on his side. Expanded travel opportunities meant that artists bent on truth in their paintings could travel to the Holy Lands and paint real landscapes and people which proved controversial to audiences used to seeing a blonde-haired and blue-eyed Jesus.

Christian ideals were an important justification for the era's wars. Even when the battles depicted were defeats, the fallen Imperial heroes are shown as the modern equivalent of Christian martyrs, winning the moral victory. A common thread in war art of this period is that the enemy rarely appears on the canvas, the attention focused on the soon-to-be fallen heroes.

'To the Memory of Brave Men': The Last Stand of Major Allan Wilson at the Shangani, Rhodesia, 4 December 1893

Subtitled ‘The Last Stand of Major Allan Wilson at the Shangani, Rhodesia, 4 December 1893’, this monumental painting depicts Wilson and his 33 men in the moments prior to their death. They are cut off from any supporting troops in a clearing, surrounded by Ndebele warriors in Zimbabwe. The warriors are hidden in the haze, othered to the point of abstraction, only suggested by the presence of discarded shields. All around the trees are torn up from bullets and the men are poised for the final, fatal onslaught that will ensure their immortality. The First Matabele War, primarily an Imperial war of expansion, is framed within familiar Christian imagery of martyrs. This is a military defeat, yet still a moral victory.

Allan Stewart (1865–1951)

Oil on canvas

H 141 x W 222.5 cm

Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum

The King's Drum Shall Never Be Beaten for Rebels, 1798

Left behind by the retreating English after the Battle of Goree in 1798, Hunter, a boy drummer of the Antrim Regiment, was commanded to beat his drum for the rebel army. With his fallen comrades at his feet, the boy kicked a hole in the instrument, retorting ‘The King’s Drum shall never be beaten for rebels’. The pikemen advance on him, bent on ending his life.

The scene depicted in the painting is entirely fictitious and there to bolster both anti-Catholic sentiment and a sense of nationalism. Like other works in this section, a painting of a defeat served many purposes, including celebrating sacrifice and bravery in the face of overwhelming odds and creating martyrs to Imperial ideal.

George William Joy (1844–1925)

Oil on canvas

H 116 x W 152.2 cm

Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum

Penance

Without the title, this painting seems to have a dreamlike quality. A young woman walks in the snow, shoeless and in a white gown. She holds a baby and a candle, with an expression of misery. Is she an outcast? Why is she risking her life and that of her child by being out in such bleak weather?

The title reveals the cause of the woman’s state. Her act of penance is to walk barefoot dressed in a robe that symbolises her baptism dress, holding a candle. The baby in her arms is the reason for this punishment. Traditionally, both unwed parents were forced to perform the penance by Hennessy chose to only show the female penitent, reflecting the societal and Biblical idea that women were to blame for sin.

William John Hennessy (1839–1917)

Oil on canvas

H 221 x W 143.2 cm

Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum

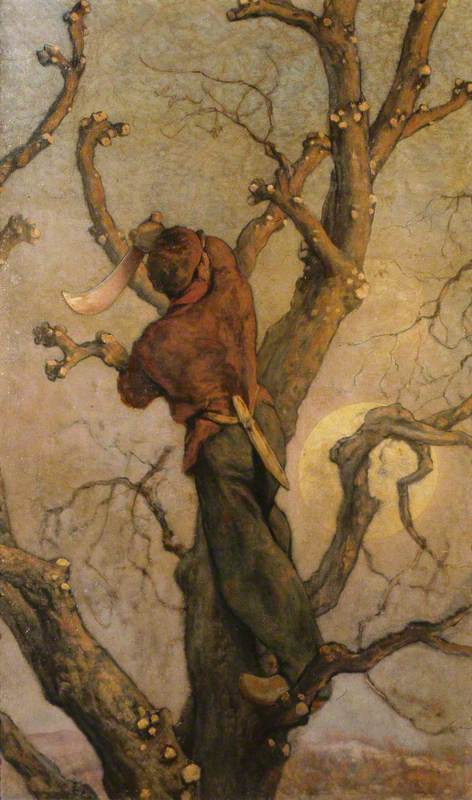

Judith

She has entered the tent of Holofernes, the leader of an invading Assyrian army, and only she can save Israel, through the power of her faith in God. The viewer can’t see Holofernes, drunk and sleeping after Judith plied him with alcohol, all we can see is Judith, poised and ready to win the war, her sword in her hand.

As a Biblical hero, Judith displays faith and beauty, typical feminine attributes but also strength and cunning, normally seen as male qualities. Depictions of Judith focus on different moments in her story, from her seduction of Holofernes, to the beheading itself, finishing with her carrying the head away to claim victory, assisted by her maid. Landelle shows Judith alone, thoughtful before her grisly victory.

Charles Landelle (1821–1908)

Oil on canvas

H 138 x W 99.5 cm

Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum

Explore artists in this Curation

View all 12-

George Sheridan Knowles (1863–1931)

George Sheridan Knowles (1863–1931) -

Briton Riviere (1840–1920)

Briton Riviere (1840–1920) -

Frank Dadd (1851–1929)

Frank Dadd (1851–1929) -

George William Joy (1844–1925)

George William Joy (1844–1925) -

William John Hennessy (1839–1917)

William John Hennessy (1839–1917) -

Abraham Solomon (1823–1862)

Abraham Solomon (1823–1862) -

Henry 'Harry' Edward John Browne (1859–1917)

Henry 'Harry' Edward John Browne (1859–1917) -

Charles Landelle (1821–1908)

Charles Landelle (1821–1908) -

Laura Theresa Epps Alma-Tadema (1852–1909)

Laura Theresa Epps Alma-Tadema (1852–1909) -

Henry Justice Ford (1860–1941)

Henry Justice Ford (1860–1941) - View all 12