George Frederic Watts (1817-1904) is best known as a painter, the 'portraitist to the Nation' and the creator of large-scale symbolist pictures. However, from the 1860s until his death in 1904, he began to dedicate substantial amounts of time to working on sculpture.

A Fragmented Legacy: G F Watts and Sculpture draws inspiration from the fascinating, if fragmentary, sculpture collection at Watts Gallery - Artists' Village, which was saved from the artist's London and Surrey studios following his death.

Visit the exhibition in person here: https://www.wattsgallery.org.uk/whats-on/g-f-watts-sculpture-fragmented-legacy/

Cast of G F Watts's Hand

The cast of an artist’s hand, especially with their tools, was a way to preserve the image of the individual ‘genius’ at work. Casts of hands could be used for drawings, or as mementoes for a marriage.

However, this cast stood as a reminder of Watts’s ambition as a sculptor. It immortalised the hand of the artist, even if he did not do most of his marble carving or bronze casting himself.

George Frederic Watts (1817–1904)

Bronze

H 11 x W 34 x D 14 cm

Watts Gallery – Artists' Village

Medusa

In Greek mythology, Medusa was a Gorgon: a terrifying winged figure with snakes for hair. Those who gazed into her eyes turned to stone. Perseus used a mirrored shield borrowed from the goddess Athena, to slay Medusa by cutting off her head.

The head of Medusa is Watts's earliest sculptural design. It dates from around 1846, and was likely made during the young artist's extended stay in Florence, Italy.

It is not known how much of this sculpture was carved by Watts himself. In her biography of her husband, Mary Watts suggests that assistants carried out the majority of the carving work, with 'the last chiselling being done by [Watts's] own hand'. The names of the assistants were not recorded.

George Frederic Watts (1817–1904)

Alabaster

H 30 x W 38 x D 32 cm

Watts Gallery – Artists' Village

Long Mary

This is an informal study of Watts's favourite model Mary Bartley. She first modelled for Watts in 1860. She modelled for numerous life-drawing sittings, the studies from which Watts continued to use, even decades later to inform his paintings and sculpture.

In this portrait Bartley is captured in a full-frontal pose (left) and a three-quarter profile view (right). The focus of Watts's attention is on the head, face and hair, which has been brushed back to fully expose her features. The background and Bartley's clothing appear as flat masses of colour, which demonstrates their insignificance to this study of the human head from multiple angles.

George Frederic Watts (1817–1904)

Oil on panel

H 53.3 x W 66 cm

Watts Gallery – Artists' Village

Clytie

In Greek mythology, the water nymph Clytie fell in love with the sun-god Helios. Rejected by her beloved, Clytie was subsequently transformed into a heliotrope (meaning ‘sun-turning’) flower, and was destined to forever turn her head to follow Helios’s daily crossing across the sky. By the 19th century the legend had evolved with the symbol of the heliotrope, a small purple flower, being replaced by the yellow sunflower, as seen in Watts’s painting. Both the painting and the bust are life-size, evoking the physical presence of Clytie. The critic William Michael Rossetti, a friend of Watts’s, described the painting as ‘perhaps his most vigorous piece of flesh-painting.’ Yet, unlike its sculpted counterpart, this version was never exhibited.

George Frederic Watts (1817–1904)

Oil on panel

H 61 x W 51 cm

Watts Gallery – Artists' Village

Clytie

Clytie was the only sculpture to be exhibited in Watts’s lifetime. When the original marble was shown in 1867 at the Royal Academy, Watts still considered the work of art unfinished.

The work was enthusiastically reviewed and in 1894, the poet and critic Edmund Gosse hailed it as the precursor of the New Sculpture movement. Clytie was seen to be a rejection against late Victorian sculpture, which was viewed as sentimental and romantic with its reliance on stiff and stylised nudes inspired by classical subjects and models.

The version you see here is an original bronze which was made around the same time as the marble bust.

Daphne

In Greek mythology, Apollo, after being struck by one of Eros's arrows, fell in love with Daphne, the daughter of a river-god. However, Daphne who vowed never to marry or let a man touch her, rejected Apollo, despite his relentless pursuit. To escape, she begged her father to rescue her. Watts's sculpture depicts the metamorphosis (transformation) of Daphne, as her father turned her into a laurel tree.

Today, the bust is strikingly angular as it was left in an unfinished state, with the marks of the sculptor's chisel still visible. The combination of the laurel leaves climbing up her arm and shoulder, and the block carving, suggests her metamorphosis is in its advanced stages.

Study of Orpheus for 'Orpheus and Eurydice'

Many of Watts's sculptural creations were temporary experiments. Rather than being finished works of art, they played a key role in the artist's creative process. Watts often made small sculptural figures in wax, clay, and plaster to use as models for his paintings. These allowed him to work out the pose and composition for the figures in his paintings without using a living model.

George Frederic Watts (1817–1904)

Plaster

H 44 x W 30 x D 23 cm

Watts Gallery – Artists' Village

Orpheus and Eurydice

Watts experimented with the story of Orpheus and Eurydice throughout his career, making multiple paintings, drawings, and sculptures based on the Greek myth. Poisoned by a snake, the oak nymph Eurydice dies and is sent to the underworld, Hades. Her husband, Orpheus, plots to rescue her by bewitching the gods with music. The gods agree to release Eurydice, on the condition that Orpheus does not look back at her as they flee.

All of Watts’s works depict the same moment of high drama in which Orpheus, having crossed to the upper-world, glances behind him. Tragically Eurydice remains on the cusp of the threshold and is drawn back into the underworld. He clings to her as she slips away.

George Frederic Watts (1817–1904)

Oil on canvas

H 66 x W 38.1 cm

Watts Gallery – Artists' Village

Study for 'Love and Life'

This large-scale plaster model is split into two parts. This demonstrates Watts working out the moment of contact and interaction between the male, winged figure of Love (right) as he tenderly guides the female figure of Life (left) up a rocky, mountainous path.

George Frederic Watts (1817–1904)

Gesso duro

H 64.4 x W 55.3 x D 41.2 cm

Watts Gallery – Artists' Village

Love and Life

This oil sketch is probably the first of more than seven canvases of the symbolic figures of Love and Life that Watts developed throughout the 1880s. He considered the work to be his 'best composition'.

This scene illustrates the notion that the strength needed to face life's challenges can only by found when faith is placed in love. Here, the two figures are brought closer together, than they are in the plaster model, with the face of Life more drastically upturned to gaze at the figure of Love.

George Frederic Watts (1817–1904)

Oil on canvas

H 66 x W 43.2 cm

Watts Gallery – Artists' Village

Study for Mary Magdalene

Mary Magdalene is one of the most famous women from the Bible. She played a crucial role in the life and death of Jesus Christ.

Created in a rather unusual three-quarter format, this head study reflects Watts's work as a leading portraitist. When painting a portrait, Watts would make studies of his sitters, both face-on and in profile to build up a more complete image of their appearance. Here, Watts has taken that process a step further by creating a three-dimensional model.

In the final painting, Mary appears in profile, but in this plaster study, Watts has captured a more complete impression of her pain and suffering.

George Frederic Watts (1817–1904)

Plaster & wood

H 27 x W 22.5 x D 12.5 cm

Watts Gallery – Artists' Village

Mary Magdalene

In this painting, Mary is shown with long flowing hair. This is because she is usually viewed as the 'woman who was a sinner' who washed Jesus's feet with her tears and dried them with her hair. Jesus forgave her sins, and she became a symbol of the repentant sinner.

This painting was originally much larger and showed Mary alone at the foot of the cross. It was damaged and subsequently cut down to leave only this expressive head study. A version of the full oil painting is in the collection of National Museums Liverpool.

George Frederic Watts (1817–1904)

Oil on canvas

H 36.2 x W 30.5 cm

Watts Gallery – Artists' Village

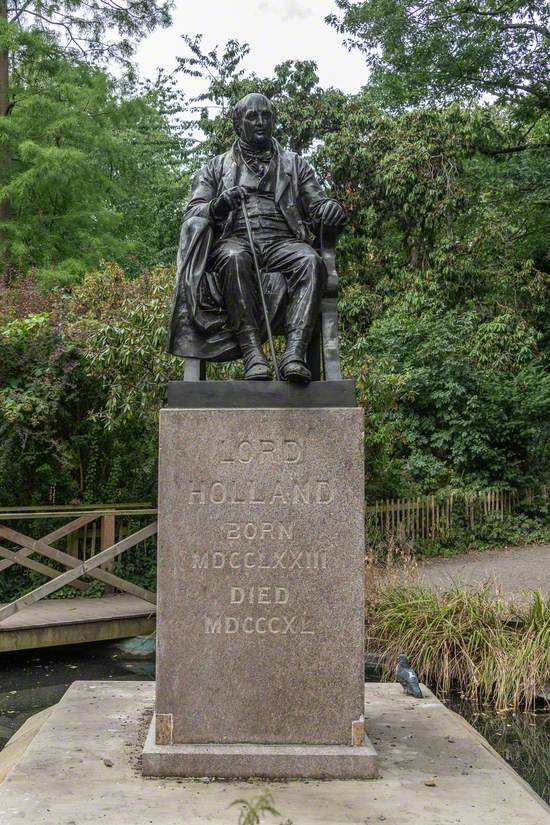

Lord Holland

This portrait is one of Watts's earliest patrons. Located in Holland Park, London, it can be regarded as the artist's first public sculpture. Henry Richard Vassall Fox, 3rd Baron Holland (1773-1840) was a politician and absentee slave-owner. He co-owned the estates of Friendship and Greenwich, and Sweet River Pen in the Westmoreland parish of Jamaica.

It is believed that Watts initially modeled the statue in clay, to be cast in bronze, as was the custom. However, due to his inexperience with the casting process, Watts asked Austrian-born sculptor Joseph Edgar Boehm to help.

George Frederic Watts (1817–1904) and Joseph Edgar Boehm (1834–1890)

Bronze & granite

H 152 x W 140 cm

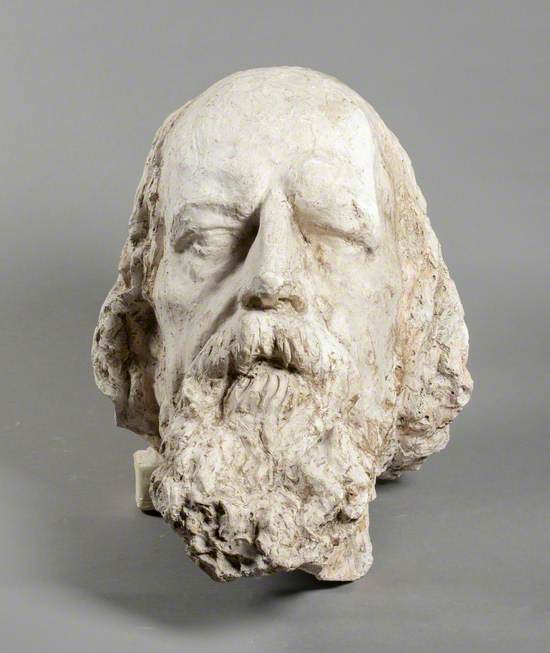

Study for Monument to Lord Tennyson

This preparatory model for Monument to Lord Tennyson is smooth and naturalistic. In contrast, in the final version, Watts was more experimental creating a heavily textured surface. This is particularly evident across the forehead and cheeks.

Watts began to work on Monument to Lord Tennyson in 1898. That year ‘the Great Barn Studio’ was bought near Limnerslease, his home here in Compton. This provided Watts and his assistants with ample room in which to work. A small railway track was also added so that the sculpture could be wheeled outdoors, enabling Watts to view it from a distance and in an open space.

George Frederic Watts (1817–1904)

Gesso grosso

H 53 x W 35 x D 40 cm

Watts Gallery – Artists' Village

Monument to Lord Tennyson

Appointed as the nation's Poet Laureate in 1850, Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-1892) was one of the most influential poets of the Victorian era. Following Tennyson's death in 1892, Watts offered to make a memorial statue of his close friend of over 30 years. The finished statue can be seen in its original location outside Lincoln Cathedral. Tennyson is depicted pondering over a small flower in his palm, while his dog, Karenina, sits patiently at his feet.

During the 19th century, studio assistants were often employed to sculpt works based on an artist's original design. Despite being in his 80s, it is believed that Watts did much of the modelling himself.

George Frederic Watts (1817–1904)

Bronze & ashlar

H 250 x W 180 x D 170 cm

Study for High Lupus and Physical Energy

Watts created this model to work out the composition and proportions of the horse and rider for his Hugh Lupus commission. Although roughly finished, Watts showed it to the newly named Duke of Westminster. Watts modified the design so that in the final sculpture, the horse's front legs are in a more naturalistic pose.

This model reveals Watts's original vision for the piece, which was intended to be a more universal depiction of a nude rider on horseback. The patron's requests, however, forced Watts to move away from his intended design, towards a more literal portrait of a historical figure. After the commission, Watts returned to the model and began on Physical Energy.

George Frederic Watts (1817–1904)

Plaster & metal armature

H 90 cm

Watts Gallery – Artists' Village

Physical Energy

Watts created this large sculpture over a 20-year period. For Physical Energy he aspired to:

'create a figure that should suggest man as he ought to be - part of creation, of [the] cosmos in fact, his great limbs to be akin to the rocks and to the roots, and he head to be the sun.'

However, during the course of its creation, and indeed after the artist's lifetime, the sculpture assumed a range of different meanings. The most problematic of which is its association with businessman and empire-builder Cecil Rhodes. You can learn more about Watts, Rhodes and Physical Energy, here: https://www.wattsgallery.org.uk/about-us/physical-energy/

George Frederic Watts (1817–1904) and A. B. Burton (active 1874–1939) and Pethick Brothers

Bronze & granite

H 300 x W 380 x D 145 cm

Explore artists in this Curation

-

Image credit: The National Horseracing Museum

Joseph Edgar Boehm (1834–1890) -

Image credit: Sally Norris / Art UK

Pethick Brothers -

Image credit: Tate

George Frederic… -

Image credit: Gordon Baird / Art UK

A. B. Burton