(b Paris, 2 Dec. 1859; d Paris, 29 Mar. 1891). French painter and draughtsman, the founder and greatest exponent of Neo-Impressionism. Seurat was the son of comfortably-off parents and his career took an unusual course: he never had to worry about earning a living and pursued his artistic researches with single-minded dedication. In 1878 he entered the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, but his studies were interrupted by military service in 1879. He returned to Paris in 1880 and for the next two years devoted himself to drawing (he was one of the subtlest and most original draughtsmen of the 19th century, typically working with very broad, velvety areas of tone, using a conté crayon on textured paper). In spite of this mastery of black and white, as a painter he turned for inspiration to artists in the colourist tradition—notably Delacroix and the Impressionists.

Read more

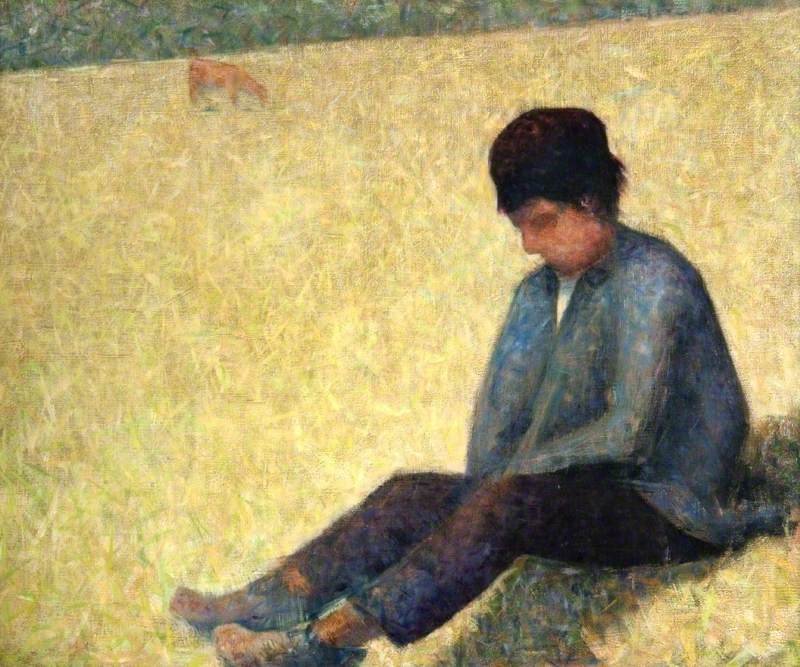

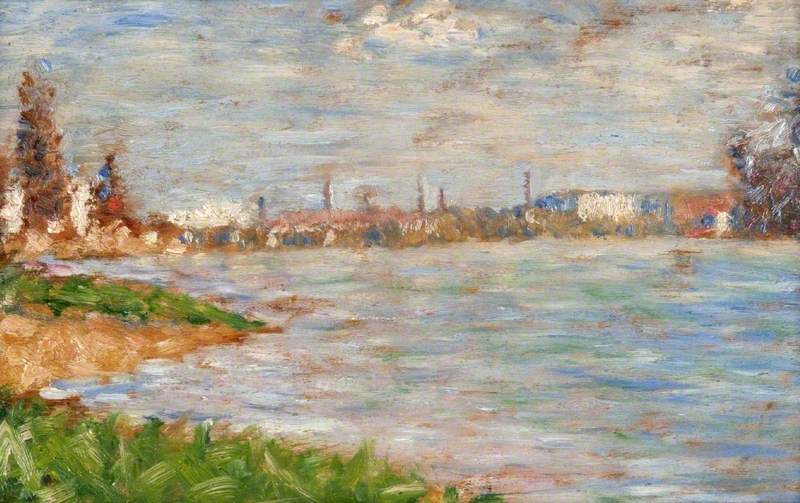

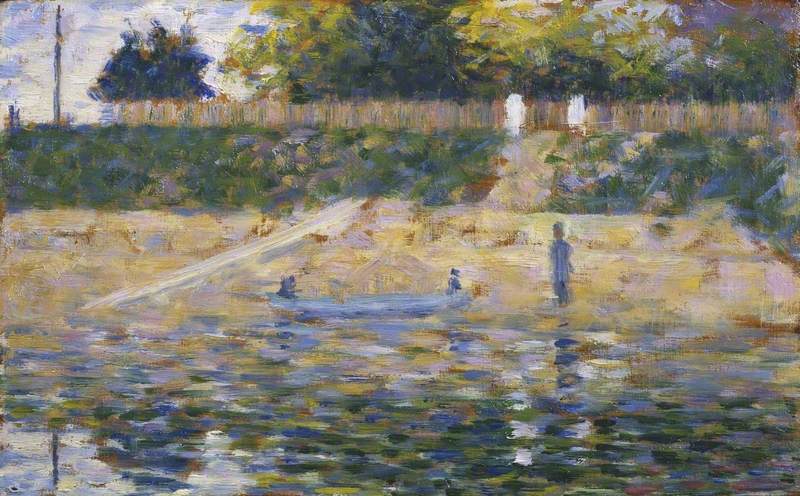

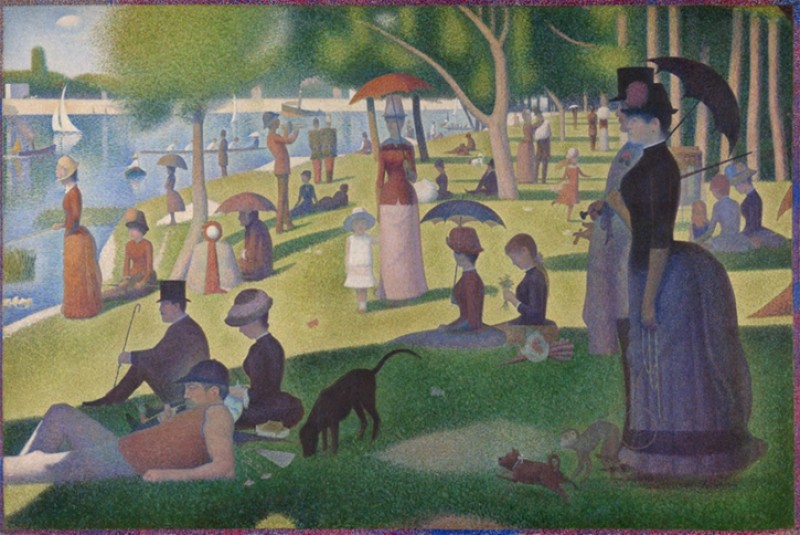

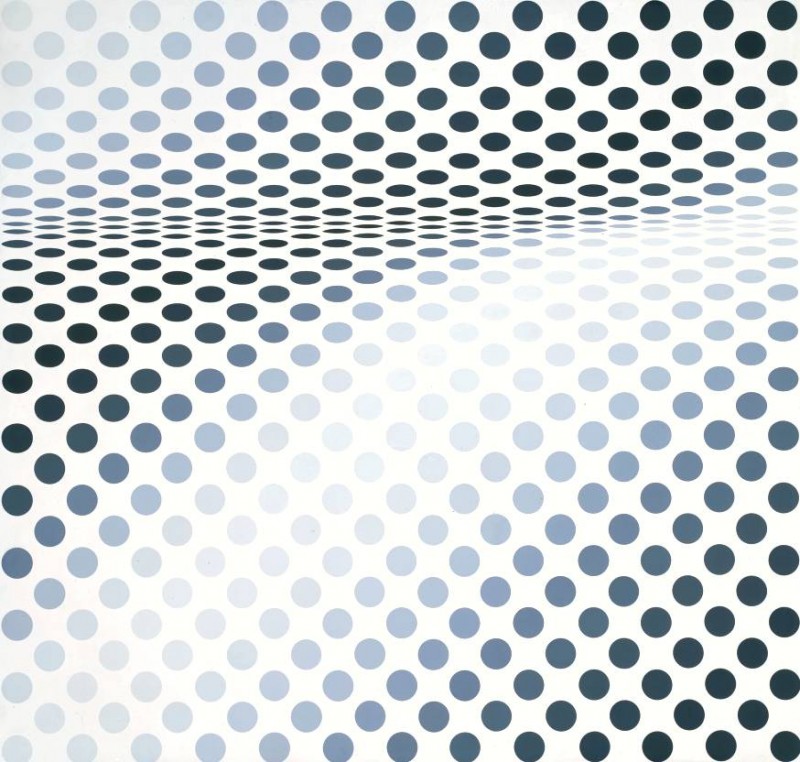

In addition to studying the work of such painters, Seurat read aesthetic and scientific treatises, and he made it his aim to create a rational system for achieving the kind of vibrant colour effects that the Impressionists in particular had arrived at instinctively. The method he evolved was to place small touches of unmixed colour side by side on the canvas, producing an effect of greater luminosity by this ‘optical mixture’ than if the colours had been physically mixed together on the palette. In his first major painting, Bathers at Asnières (1883–4, reworked 1887, NG, London), Seurat was still experimenting with his technique, but his next large work, Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884–6, Art Inst. of Chicago), is a completely mature statement of his ideals. La Grande Jatte was shown at the final Impressionist exhibition in 1886 and led to the recognition of Seurat as a leader of the avant-garde. The critic Félix Fénéon coined the term pointillism in reference to this painting to describe the technique of using myriad dots of colour, but Seurat himself preferred the term divisionism.From 1887 Seurat began to turn his attention to the significance of line in painting, believing that certain directions of lines could express specific emotions: horizontal lines represented calmness, for example, while upward- and downward-sloping lines represented happiness and sadness respectively. He embodied his ideas in works such as Le Chahut (1890, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo), in which the raised legs of the dancers performing ‘Le Chahut’ (a sort of cancan) express ‘happiness’. Seurat died very suddenly at the age of 31, evidently from meningitis, although his friend Signac said that he ‘killed himself by overwork’. He was so dedicated to his art and kept himself to himself to such an extent that until his death few people knew he had a mistress and son. His mistress, Madeleine Knobloch, is represented in Woman Powdering Herself (1890, Courtauld Gal., London). Seurat's work was highly influential, but his disciples rarely approached his skill, and even less his level of inspiration, in applying his theories: their paintings often look mechanical and lack his gently satirical humour. In power of composition he stands above not only his followers, but also virtually all other painters of his period. He planned his pictures with extraordinary care, and they have nothing of the sense of the passing moment associated with Impressionism. Rather, they have a highly formalized quality and a conscious grandeur that has caused Seurat to be compared with such revered masters as Piero della Francesca and Poussin.

Text source: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford University Press)