In a letter written in the early 1930s, Helen Sutherland described herself as having a 'rather Abbess-like feeling in this Abbey-like house of Rock'. Rock Hall – the 'Abbey-like house' – was not so much an austere monastery (although Sutherland was renowned as a frugal and fastidious hostess), as it was a decadent, comfortable Regency era manor house – decorated with modern art, beautiful furniture, and books and magazines sent for from London.

Rock Hall School, Northumberland

As the 'Abbess', Sutherland's charges were not a worshipful gaggle of young nuns or unruly monks, but instead a revolving cast of painters, poets, and writers. The artist-couple Ben Nicholson and Winifred Nicholson, the painter and modernist poet David Jones and the critic and scholar Kathleen Raine all stayed with Sutherland, along with an ever-changing rabble of friends and children.

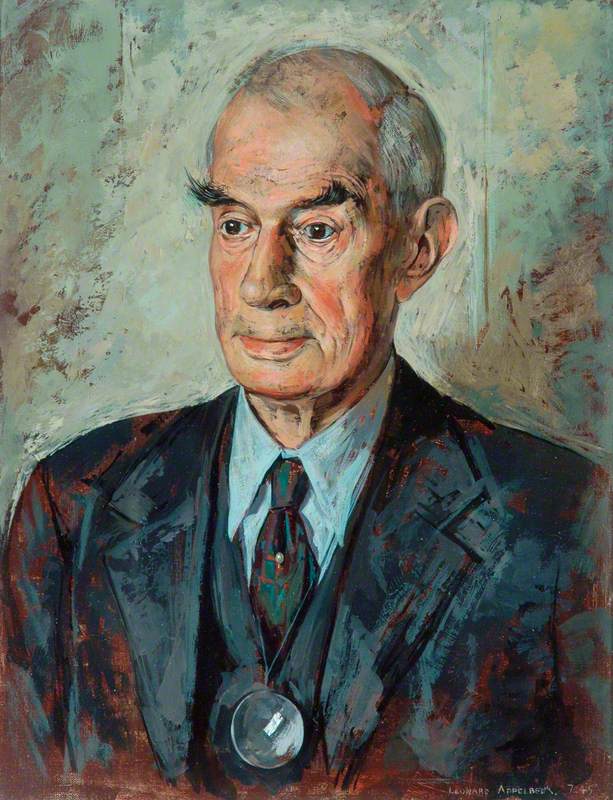

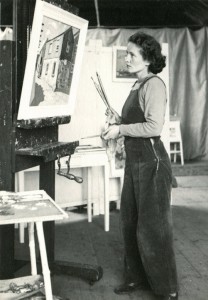

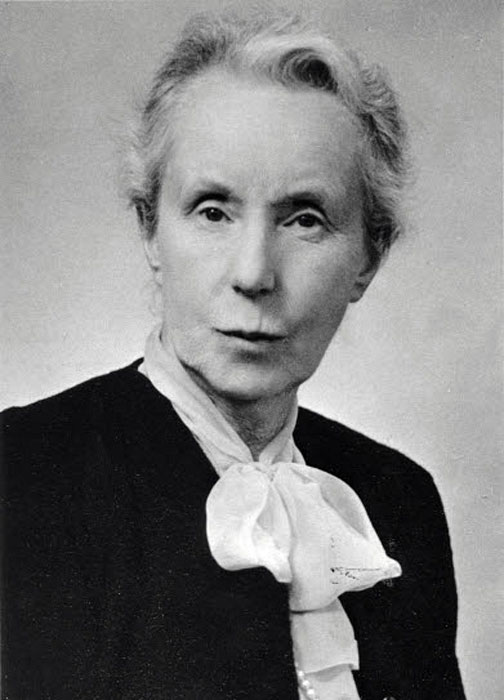

Helen Sutherland

photograph, c.1966 by unknown artist

By the time she moved to Northumberland's Rock Hall, Sutherland was something of an incongruous 'Abbess' of the modern art world. Born in 1881 into a stuffy, Victorian environment, Sutherland's early life was more fitting for an existence of religious contemplation than radical art collecting. She grew up in the quiet countryside of Hampshire, and, after a spell at boarding school in Barnet, spent time at a convent in Paris. She was married at the age of 23 to the politician Richard Denman, but initiated an annulment nine years later: the marriage had never been consummated.

After her mother Alice, Lady Sutherland died in 1920, and her father Sir Thomas Sutherland died in 1922, Sutherland came into a considerable fortune – her two brothers had died, and left her as the sole heiress. But, rather than frittering her money away on the temptations available to a single woman in 1920s London (dresses, balls, society gatherings), Sutherland retreated to an ascetic life of art collecting: she supported artists and writers, and filled her rural houses with paintings, drawings, and sculptures – many of which now make up the exhibition 'Truth and Beauty – The 20th Century British Art of pioneering art collector Helen Sutherland' at The Maltings in Berwick, Northumberland.

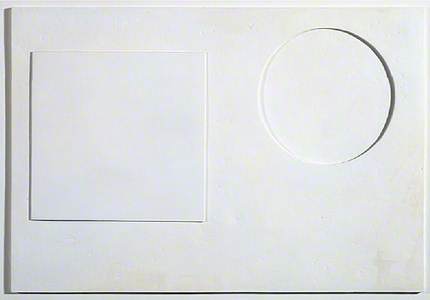

Installation view of 'Truth and Beauty' at The Granary Gallery

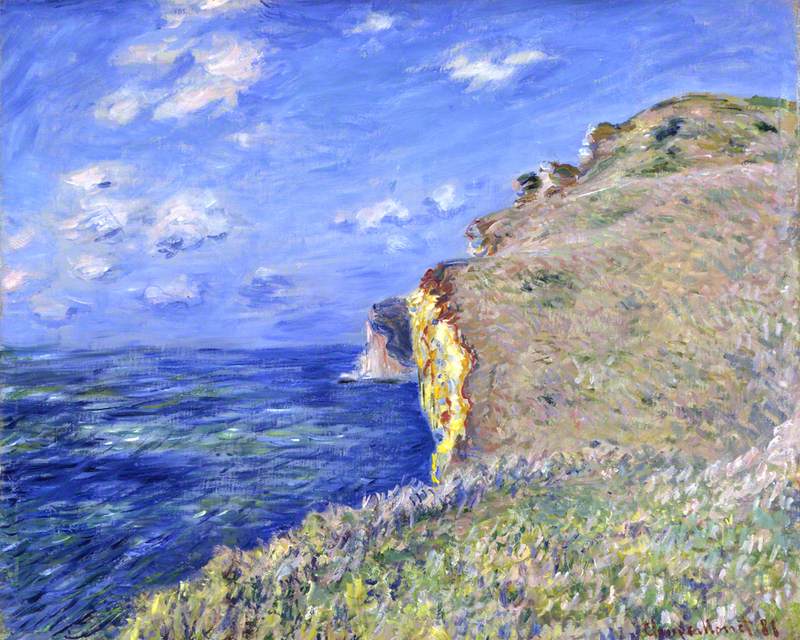

In the early twentieth century, modern art was not revered in Britain. In 1910, the painter, critic, and member of the Bloomsbury Group, Roger Fry staged an exhibition at the Grafton Galleries in London called 'Manet and the Post-Impressionists'. Londoners were not delighted by the possibility to see works by the group Fry designated as 'Post-Impressionists' following in the style of Édouard Manet: Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Henri Matisse. The bold, abstract paintings and vivid, unnatural colours were a shock to visitors.

Virginia Woolf remembered crowds in 'paroxysms of rage and laughter', whilst one critic claimed that the show was part of a 'widespread plot to destroy the whole fabric of European painting'. The year 1910 was too early for such modernity in Britain: gallery-goers had only just gotten over the shock of the countercultural Pre-Raphaelites.

By the 1920s, little had changed in the British public's artistic sensibility. In 1925, a carved relief by the sculptor Jacob Epstein was installed in Hyde Park.

As a memorial to the much-loved Victorian naturalist writer William Hudson, the relief should have been adored and appreciated. But Epstein had made a cardinal mistake: his 'Rima' – the goddess of nature who features in one of Hudson's novels – was depicted nude. Outroar and horror ensured, and a petition that declared that the work was an 'inappropriate and even repellent' piece of 'artistic anarchy' was signed by all from the Sherlock Holmes author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to the artist Alfred Munnings.

It was into this world of artistic prudishness that Sutherland entered in the early 1920s. Amidst a whirlwind of seeing ballets, plays, and concerts (she was a friend of the pianist Vera Moore, who gave her lessons), and reading modernist literature (books by James Joyce and Virginia Woolf littered her houses), she began to collect art.

She ignored the hysteric response to Fry's 1910 Post-Impressionist exhibition, and bought a painting by Georges Seurat which is now in the National Galleries of Scotland, A Study for 'Une Baignade' (c.1883) – an earlier version of his far more famous work, Bathers at Asnières (1884).

Sutherland did not agree with the critic who had hailed the Post-Impressionists as the death knell for the 'whole fabric' of European art, and instead wrote in her diary that it was such 'a tiny picture but so lovely, simple and full of significance'. She appreciated the elements which had so scared the other critics. She was not put off by the bold colours, but instead praised 'such loveliness in the shadows and the air and spirit over it all'.

Sutherland was a fan of other contemporary artists: she travelled to Paris to see works by Cézanne, and bought paintings by André Derain. And nor did she have a solely European focus. She bought Persian and Mughal miniatures – some of which were later exhibited at the Royal Academy in their International Exhibition of Persian Art.

But, in 1925, Sutherland's art collecting altered and, along with it, the history of contemporary British art. In November, her artist friend Constance Lane introduced her to Ben and Winnifred Nicholson. The tea party was a success, and, in just over a month, Sutherland had bought two works already.

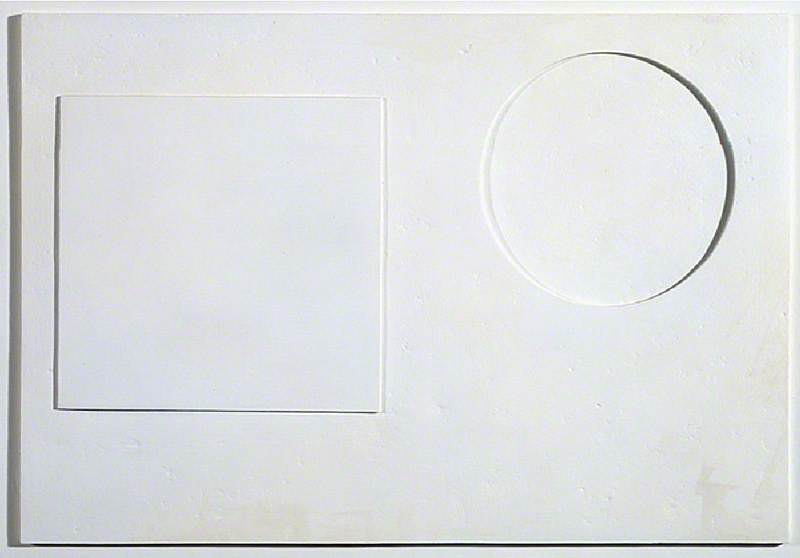

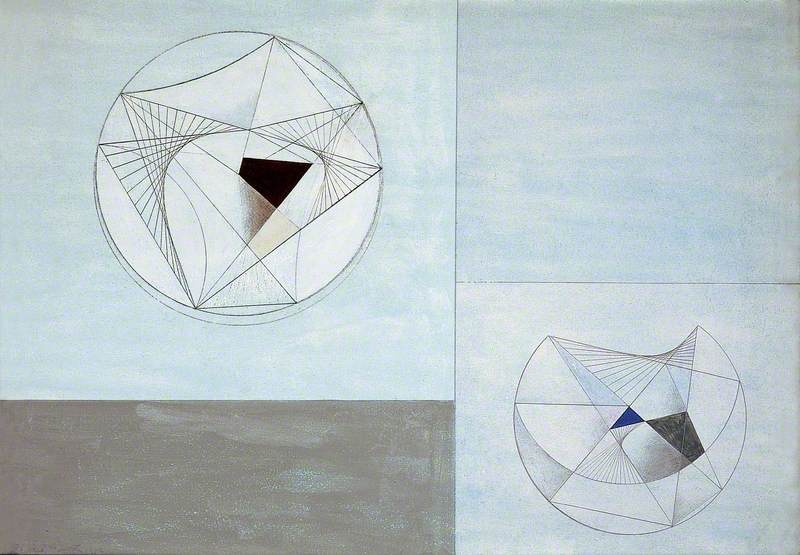

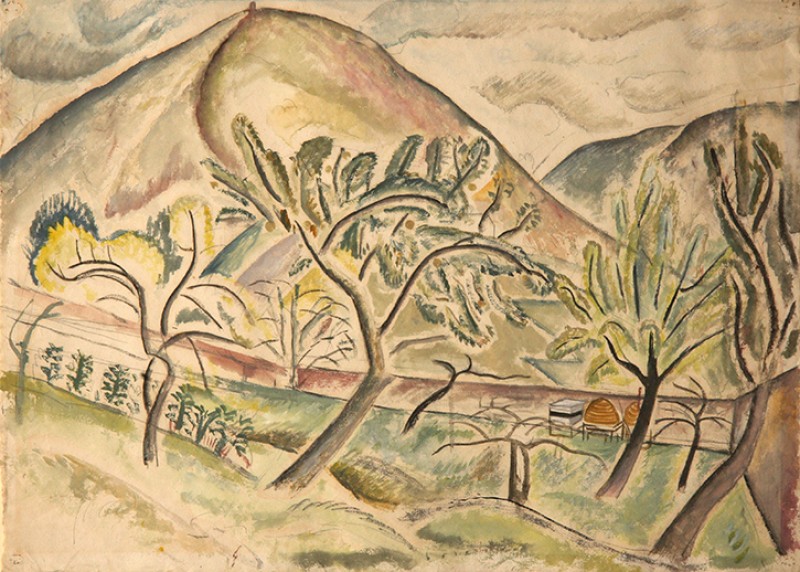

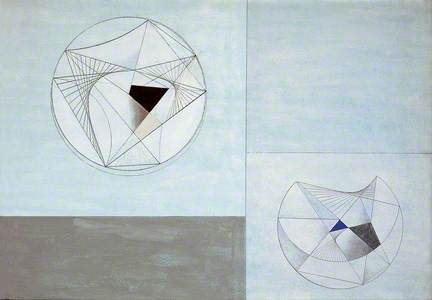

By the 1920s, Ben Nicholson had started to work with abstract, geometric forms – akin to the later white reliefs he is now most famous for. Winifred's paintings (his wife until they divorced in 1931, and Ben and Barbara Hepworth began a relationship) are more representational. In her diaries, Sutherland described Winifred's world as 'a lovely world of flowers and a few people', and Ben's as one of 'strange brooding figures and radiant clouds'.

Daffodils and Hyacinths in a Norman Window

c.1950–1955

Winifred Nicholson (1893–1981)

At the time that Sutherland met the Nicholsons, their work was not popular: Sutherland's lifelong friend Edward Hodgkin would later write that it required 'courage as well as taste' to buy these works by 'young artists who were known to a few and admired by even fewer'. Courage and taste Sutherland had in spades: by the time of her death, she owned 47 works by Ben Nicholson, and bequeathed another 42 to public collections.

She owned a considerable number by Winifred too, but as Nicolette Gray – a curator and long-time friend of Sutherlands – once wrote, Sutherland 'kept a record of the wine she bought... of plants for her garden, but none of her paintings'. As such, it is sometimes hard to ascertain which works she did buy, but she certainly owned two paintings by Winifred which are now in Kettle's Yard.

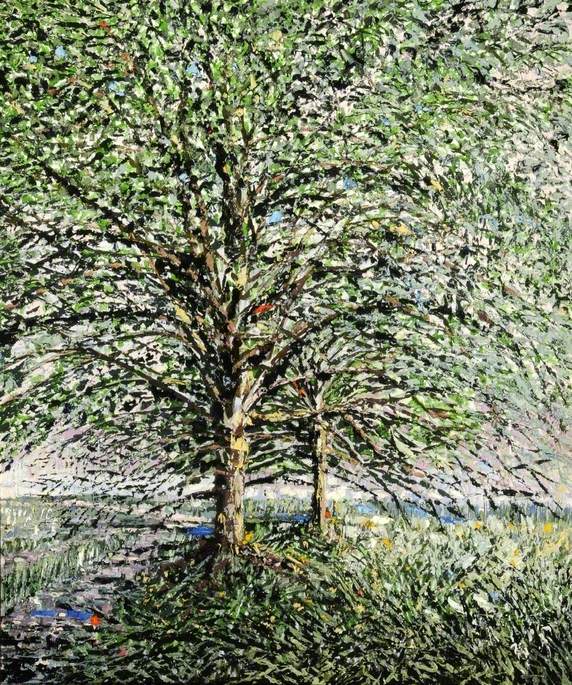

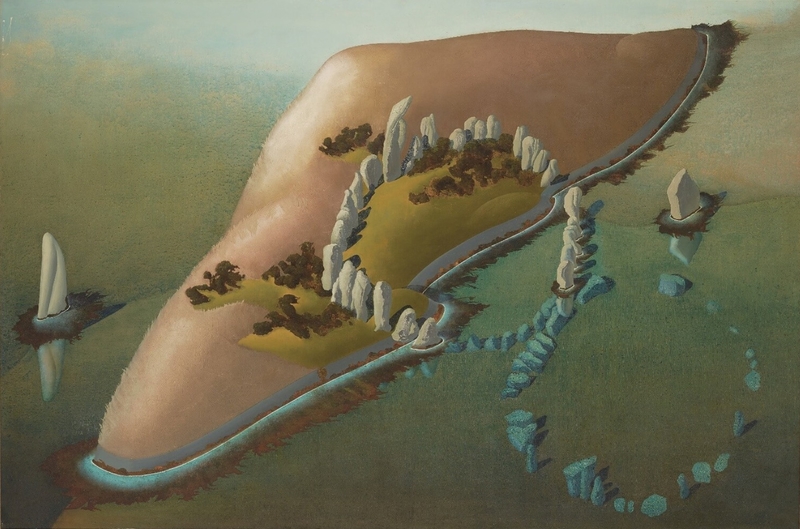

But it was not just through buying works that Sutherland helped these artists. In 1928, she bought Rock Hall – the 'Abbey-like' house in Northumberland. This rural, large house became the home of a band of itinerant artists who were encouraged to stay and work there. David Jones even had his very own room in the house – and painted the view from his window in The Chapel in the Park (1932), which is now in the Tate collection.

The Chapel in the Park

1932, watercolour on paper by David Jones (1895–1974)

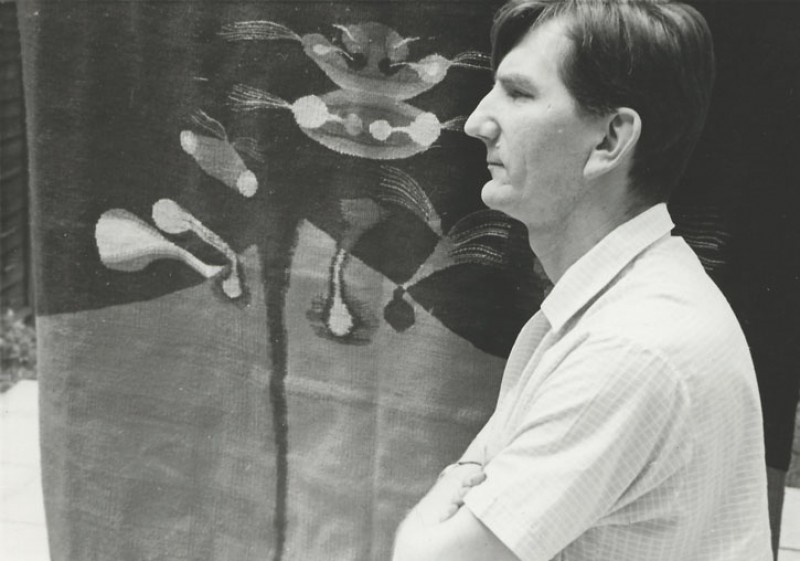

Jones was a particular favourite of Sutherland's, and she doted on him after his first breakdown in 1932 (caused, in part, by his experience of the First World War). He often painted from his room at Rock, and Sutherland came to own the largest collection of paintings by him – many of which are now in public collections.

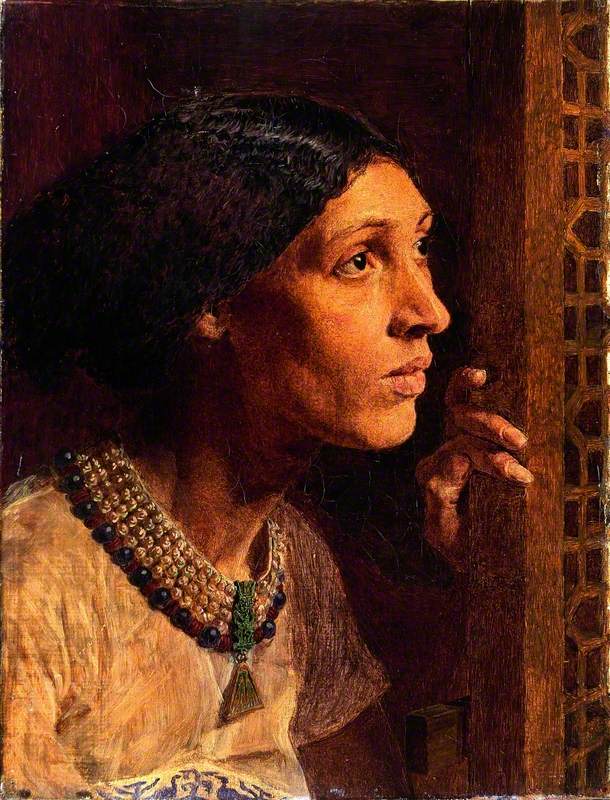

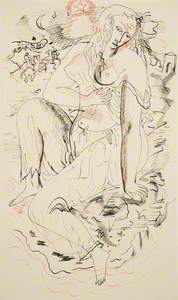

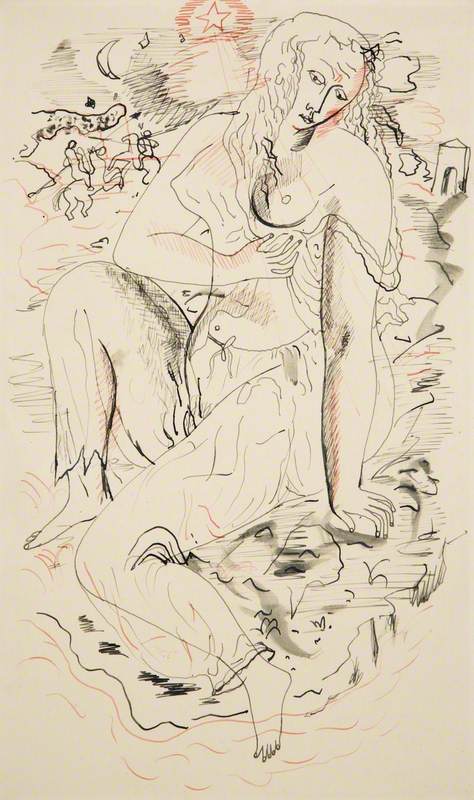

Woman Seated in a Landscape

(also known as 'Aphrodite in Aulis') c.1940

David Jones (1895–1974)

When talking about her collection in later years, Sutherland would note that her works form a 'family party in which some of the members probably disapprove of the others, yet they share this family connection'. This was true of the breadth of her acquisitions: after she was introduced to the Nicholsons, she very rarely collected art to which she did not have a connection to the artist, but her collection still ranged across the avant-garde of British art, from the sculptor Henry Moore to the St Ives-based artist Wilhelmina Barns-Graham.

But this 'family' connection was also true in the way she treated the artists who fell into her circle. She was unfailingly generous – and even helped Barbara Hepworth buy the workshop and garden in St Ives that would be so crucial to her later work. Sutherland encouraged collaboration and bought art into the village community at Rock: both Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson designed aspects of the village chapel – the same chapel that David Jones had drawn from the window.

One part of this 'family party' was the Ashington Miners Group – a group of miners who, under the tutelage of Robert Lyon, began to paint and formed 'The Pitman Painters'. Sutherland counted one of the founding members, Arthur Whinnom, as a lifelong friend – and collected his work alongside her other artistic darlings.

After her death in 1966, much of Sutherland's 'family' of art was split up and vanished into private collections, but this exhibition – and the works that remain in public collections – are a chance to see the evidence of her wonderful taste, judgment, and artistic encouragement.

Francesca Peacock, freelance writer

'Truth and Beauty – The 20th Century British Art of pioneering art collector Helen Sutherland' at The Maltings in Berwick, Northumberland is on until 9th October 2022