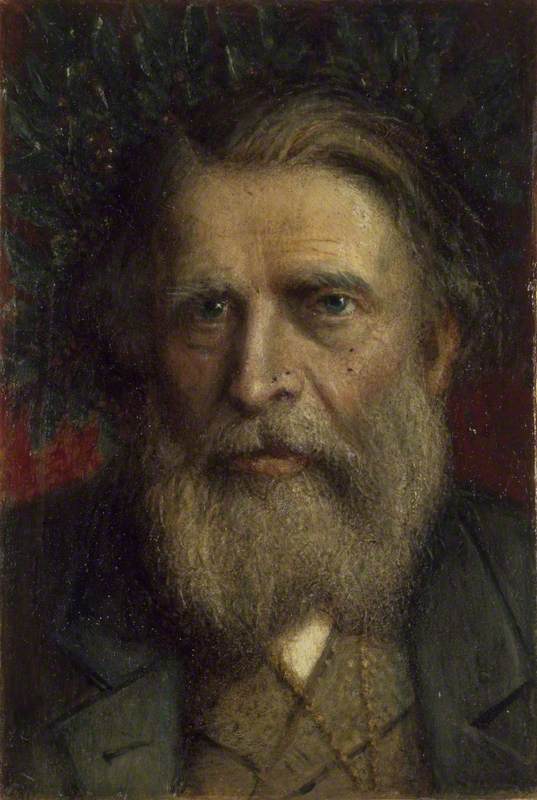

John Ruskin was born at 54 Hunter Street, Brunswick Square, London, England on 8 February 1819 and moved with his parents to 54 Hunter Street in Herne Hill, Surrey in 1823. In 1837 he enrolled at Christ Church, Oxford. Because of ill-health he was forced to withdraw in 1840 but returned in 1842 to take his degree. In 1839 he won the Newdigate Prize for poetry. During a break from Oxford, he developed a passion for the work of the painter J.M.W. Turner (1875-1851) whom he met and whose paintings he began to buy.

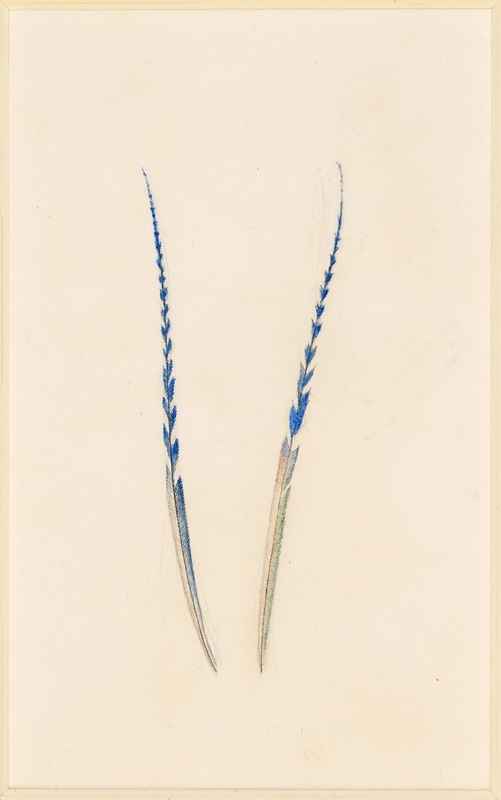

During this period, he also visited Venice, which left a lasting impression, and discovered his vocation as an art critic. In 1842 he read a newspaper review of that year's Royal Academy Exhibition, which included an attack on Turner's contribution. Ruskin was incensed and announced his intention "to write a pamphlet and blow the critics out of the water". What was to be a pamphlet subsequently evolved into a five-volume work, Modern Painters: their Superiority in the Art of Landscape Painting to the Ancient Masters (1843, 1846, 1854, 1860). In Modern Painters he heaped praise on Turner and asserted that modern painters were. in many respects, superior to the old ones. In 1851 Ruskin was to come to the defence of the Pre-Raphaelitite Brotherhood when three of its members: John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt and Charles Allston Collins were attacked in The Times of 7 May 1851 which asserted that they had "no real claim to figure in any decent collection of English painting." Within weeks Ruskin fired off two letters to The Times. In the second, published on 30 May, he claimed that as they gain experience the PRB may "lay in our land the foundations of a school of art nobler than has been seen for three hundred years”. Later that year Ruskin followed the letters up with a pamphlet entitled, Pre-Raphaelitism (1851) in which he further clarified his views about the group. The Pre-Raphaelites in turn were inspired by Ruskin. They took his call to return to nature seriously, and like him, they idealised the mediaeval era.

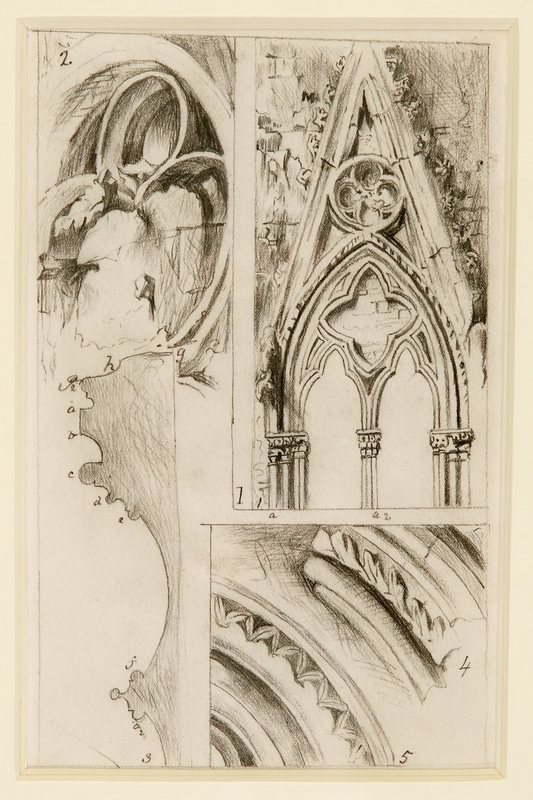

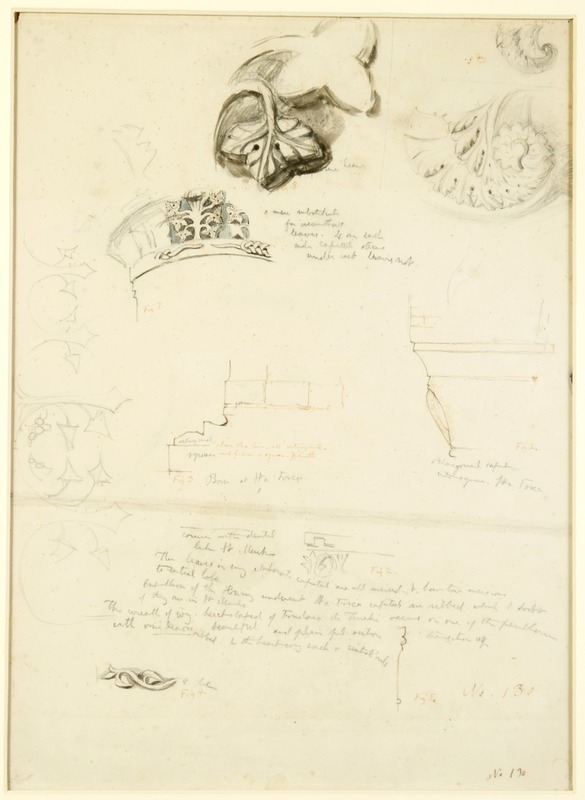

Just as he championed modern painting, Ruskin was equally enthusiastic about the Gothic style of architecture which he believed could be adapted to the Protestant church. He outlined his views on Gothic architecture in his book The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849) and in the chapter, "The Nature of Gothic" in the second volume of his three-volume work The Stones of Venice (1851-53).

In August 1869, Ruskin was appointed the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford University and in 1871 he founded his own art school at Oxford, The Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art.

From the 1860s Ruskin became increasingly concerned with the cultural condition of his age and through his inheritance, he was able to finance idealistic social causes. In 1871 he founded the Guild of St. George. [prior to 1878 it was called the St George's Fund, and then St George's Company]. The Guild "represented Ruskin's practical response to a society in which profit and mass-production seemed to be everything, beauty, goodness and ordinary happiness nothing." Through the Guild he hoped to "promote the understanding and appreciation of good art, to encourage craftsmanship rather than mass production, and to revive what we should now call sustainable agriculture and horticulture." [Website of the Guild of St. George].

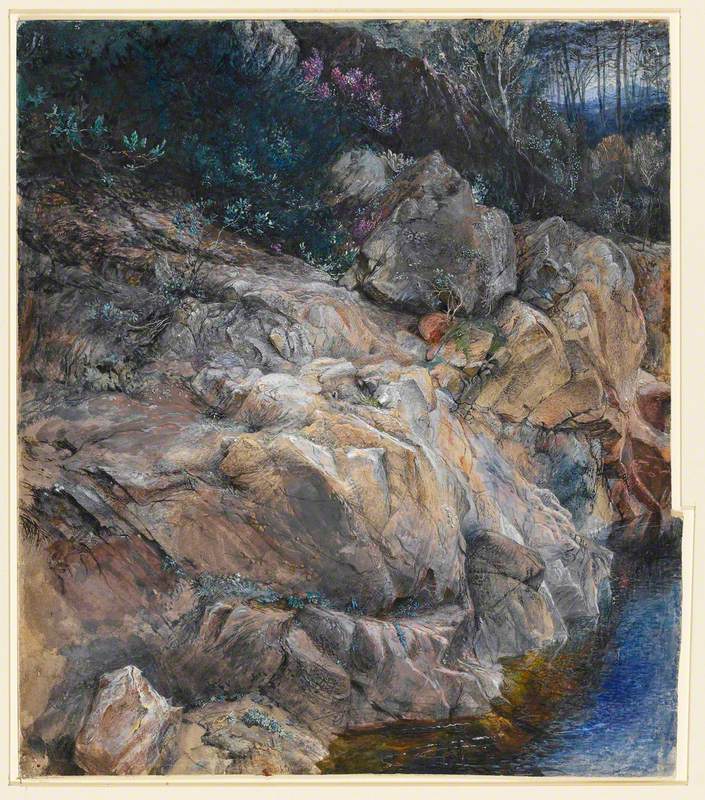

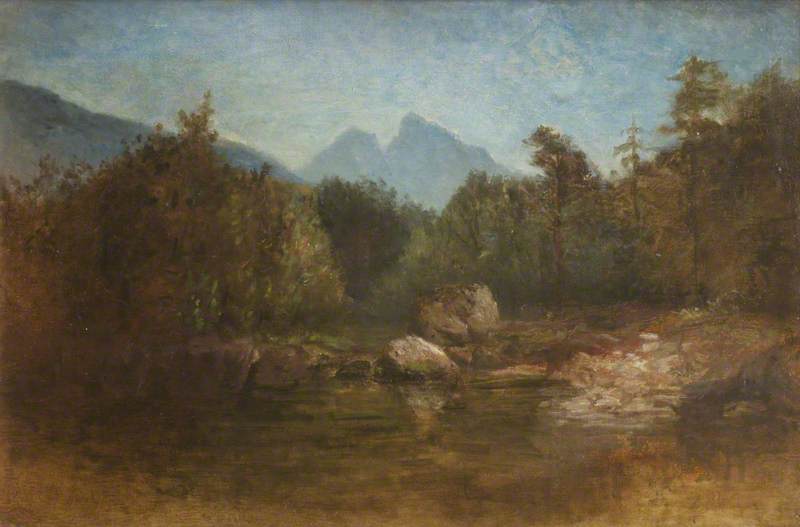

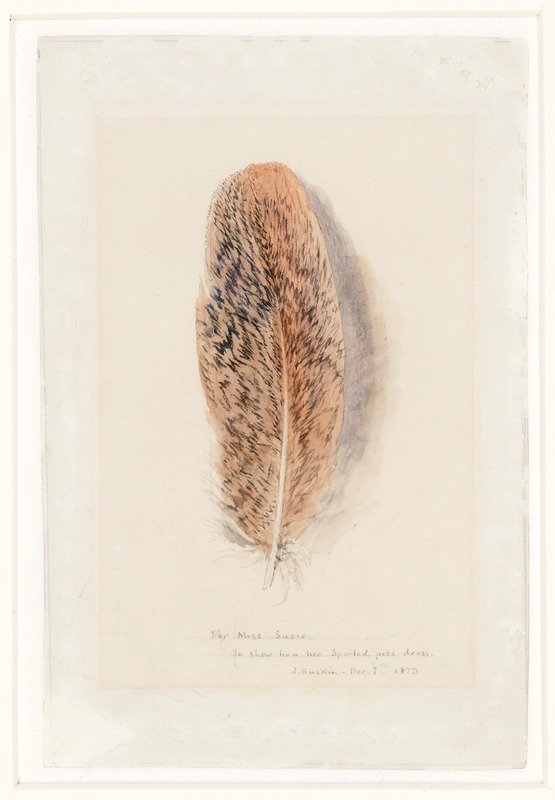

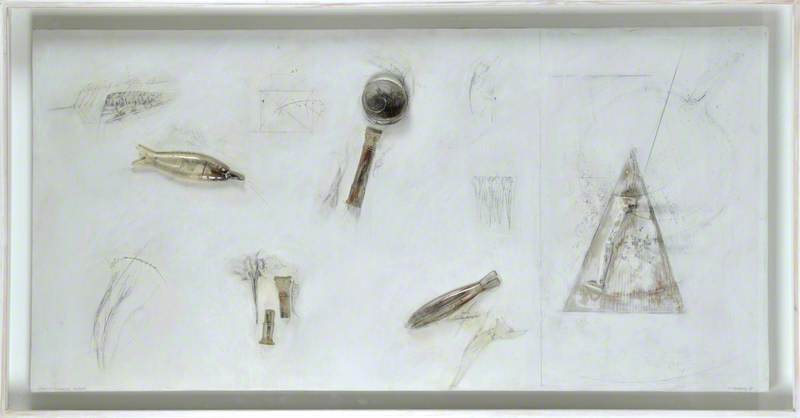

Ruskin was a talented watercolourist and between 1873 and 1884 exhibited at the Old Watercolour Society and elsewhere.

The last decade of Ruskin's life were blighted by mental illness. He died at his home, Brantwood, in Coniston, Lancashire on 20 January 1900.

Ruskin had a profound influence not just on his contemporaries but on later generations of artists and writers worldwide. In his essay How I Became a Socialist (1894), William Morris wrote ". . . how deadly dull the world would have been twenty years ago but for Ruskin! It was through him that I learned to give form to my discontent, which I must say was not by any means vague. Apart from my desire to make beautiful things, the leading passion of my life has been and is hatred of modern civilisation."

Text source: Art History Research net (AHR net)