'For me, drawing is an inquiry, a way of finding out,' the English artist Bridget Riley once observed. 'The first thing that I discover is that I do not know.' Wyndham Lewis dubbed drawing 'the frailest of the visual arts' yet one that 'possesses far greater endurance' than its counterparts: 'Mere scraps of paper that it is, in this respect it has more vitality than basalt.'

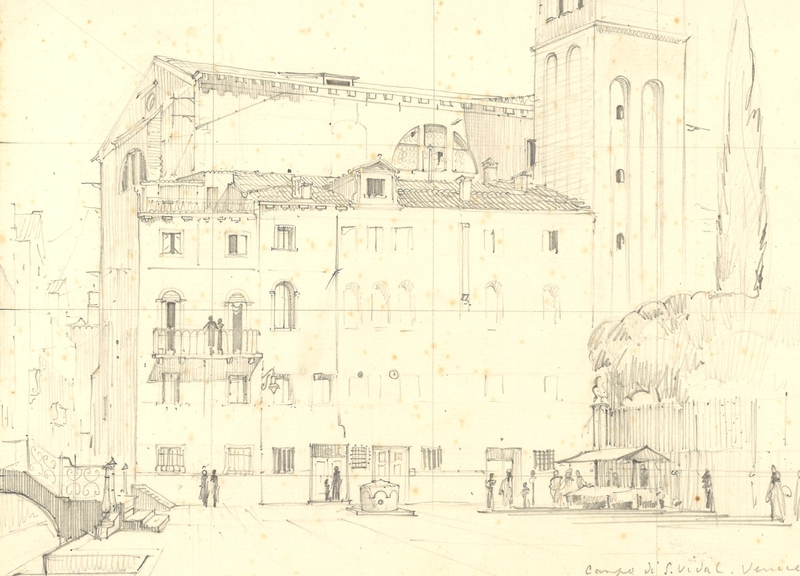

Venice, like drawing itself, is elusive, changeable, ancient but modern, fragile but enduring. Is it any wonder artists have tried and failed, again and again, to capture it with pencil and paper?

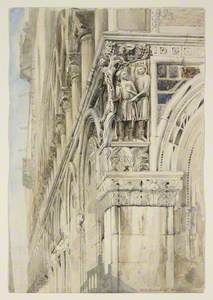

Image credit: University of Dundee Fine Art Collections

St Mark's Basilica, Venice 1898

Axel Herman Haig (1835–1921)

University of Dundee Fine Art CollectionsThere is an inherent tension at work when drawing: observing and acting, seeing and creating – a push and pull that matches the tidal movements of the Venetian lagoon. Drawing Venice can at times appear as a herculean task, a desperate attempt to freeze a thing that cannot be frozen. The floating city presents a challenge in the rippling lines of the waves, of water both in the canals and reflected shimmering upon its stones.

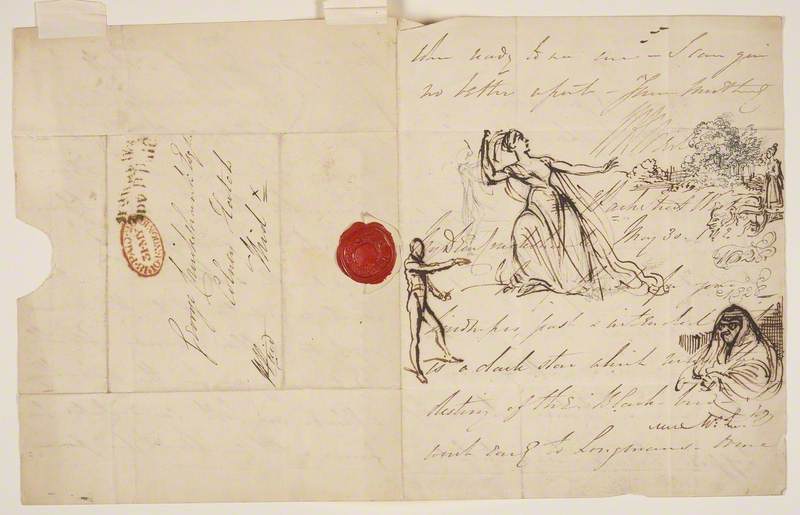

Yet people have been drawing Venice for centuries, attempting to capture the absurd phenomenon of a city on water. A few years ago, in 2020, what is now thought to be the earliest known drawing of Venice was uncovered: a fourteenth-century sketch by Niccolò da Poggibonsi, a travelling friar who was on pilgrimage to Jerusalem from Italy between 1346 and 1350. In the drawing we see his integration of the city, the buildings crammed together in a quasi-bird's eye view with boats, houses, and churches all jostling for attention, bridges reaching out across hurried dashed lines of waves. It's a reminder that a lot of what a drawing is is also what it's trying to do. Inform? Record? Express? For Poggibonsi, the simplistic style leans toward the educational. The act of drawing is an attempt at explanation, the very fact of creating it an act of evidence for the existence of such a fantastical-sounding city.

Interior of the Redentore, Venice, with Figures 1746 or 1766

Antonio Visentini (1688–1782) and Francesco Zuccarelli (1702–1788) and Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696–1770)

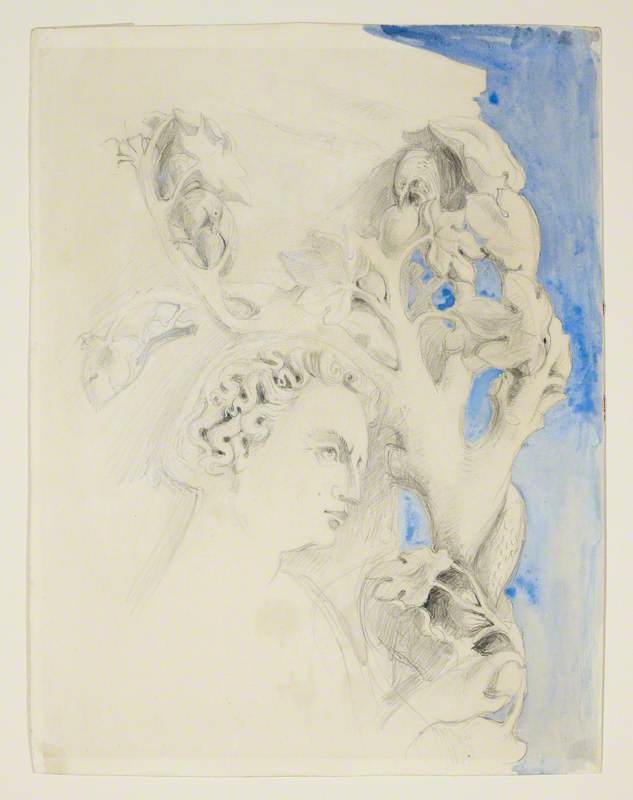

The Courtauld, London (Samuel Courtauld Trust)There are drawings, like Venice itself, that are built up in layers – different authors, different styles, coalescing in a delicious mix. In Interior of the Redentore, Venice, with Figures (1746 or 1766), Giovanni Battista Tiepolo comes together with Antonio Visentini and Francesco Zuccarelli to draw a vast interior space. The architecture of the drawing is rendered in pen, brown ink and grey wash, while black and white chalk have been used to render the figures that populate the scene, each part distinguished by a different artist's hand.

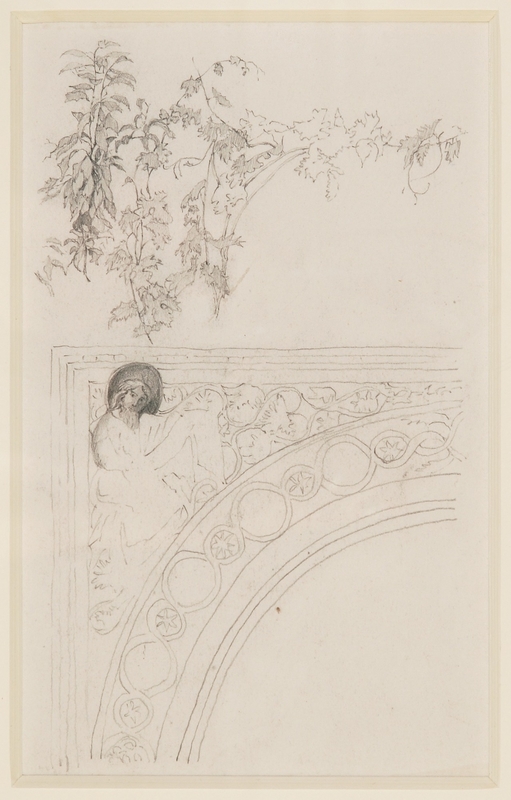

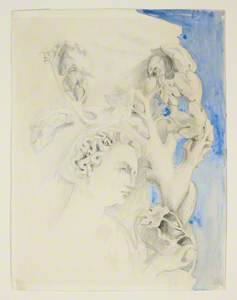

Image credit: Collection of the Guild of St George, Sheffield Museums

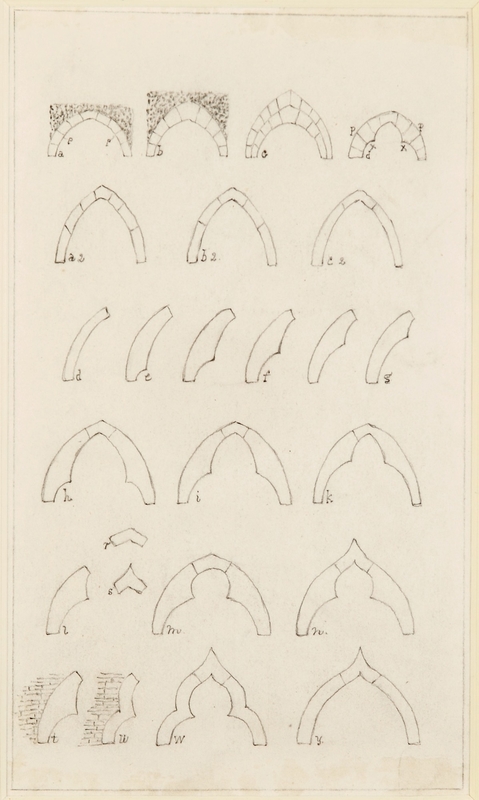

'Arch Masonry', Study towards 'The Stones of Venice', Volume I about 1851

John Ruskin (1819–1900)

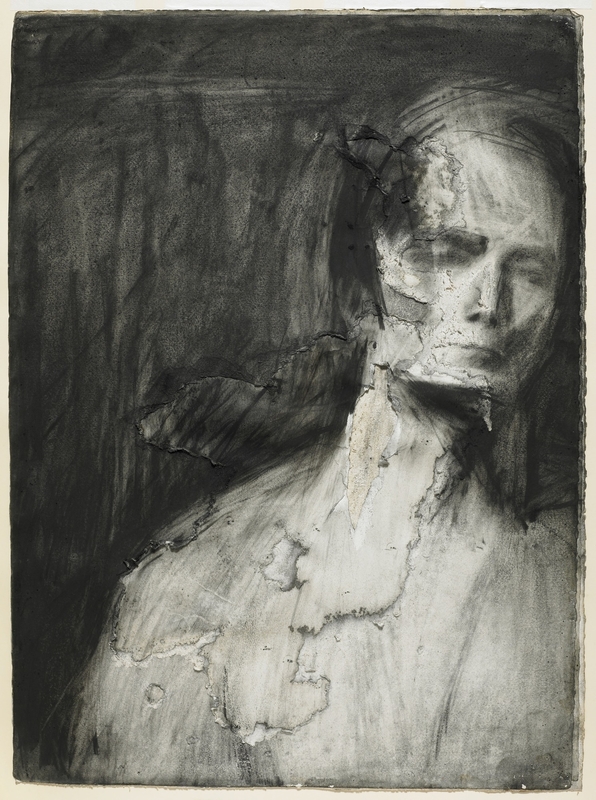

Sheffield MuseumsYet just as Venice can be built up in layers, it can also be broken down through focused attention to detail. One of the most famous recorders of Venice was John Ruskin, who practically took the city apart brick by brick in his three-volume The Stones of Venice (1851–1853). Ruskin's surgical studies for The Stones of Venice isolate and fragment the city's architecture, breaking it down into dynamic sections. Take his 'Arch Masonry', Study towards 'The Stones of Venice', Volume I, where each curve, each arch becomes akin to a bone, lifted from the skeleton of the grander picture and given new life. Isolated upon the blank page, redrawn and redrawn again from every angle, we find each structural part becomes a protagonist all of its own. Through Ruskin's drawings we see how the spirit of a building can be lifted from the world and placed on paper: his architectural specificity, the ability to concentrate and focus on the buildings of Venice so intently, gives them life.

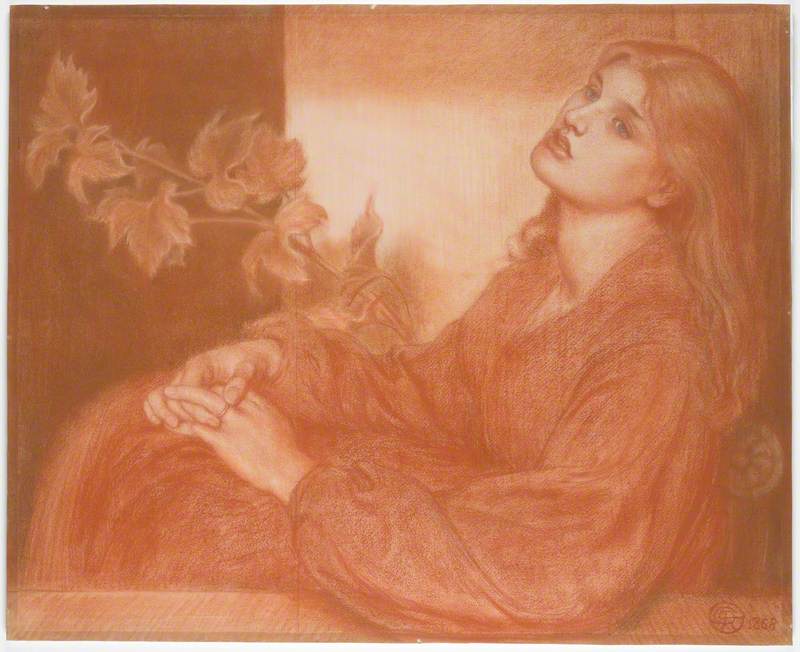

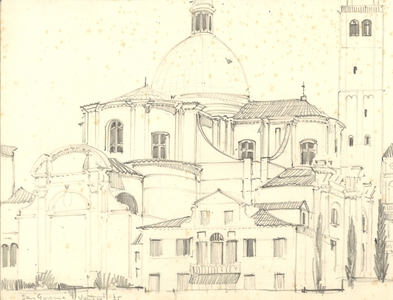

Image credit: Manchester Art Gallery

Façade of The Doge's Palace, Venice – The Vine Angle c.1870

John Ruskin (1819–1900)

Manchester Art GalleryRuskin's realism presents Venice as a test of technical precision. His drawings are a means of preserving the city. But Venice can also transform into a mirror, with drawings shifting from accurate depictions to become a reflection of the artist. We see this even within Ruskin's own sketches, which evolve and develop over time. Certain subjects thrum with energy, no longer cold stone but filled with vibrating, quivering lines of sight.

Venice is such a vast subject one can't possibly take it all in at once: like Ruskin, we must dissect. In William Callow's ghostly Grand Canal (1880), the wavering outlines of the palazzos sit as a collective community bound by energetic lines and interconnected walls. Neighbouring houses jostle for attention, united by form. Yet Callow refuses to draw the sky or water that should bracket these man-made constructions, allowing these forms to hover instead, the columns of bricole and jetties simply floating in space, removed, much like Venice, from the rest of the world.

Meanwhile in John Piper's depiction of Ca' Pesaro from 1971, a terraced window juts out, highlighted in squiggles of white chalk. Our eye is drawn to what Piper wants us to see. Similarly in the sketches of Christiana Jane Herringham, her use of colour illuminates points of interest and intrigue: in St Mark's Basilica, Columns and Arch she channels our attention to the coloured flagstone floor in chequerboard red and white.

Image credit: Royal Holloway, University of London

Italy: Venice – St Mark’s Basilica, Columns and Arch late 19th C–early 20th C

Christiana Jane Herringham (1852–1929)

Royal Holloway, University of LondonThe Bloomsbury Group's Duncan Grant almost removes our attention from the setting of Venice altogether. His View from a Window in Venice places a bowl of ripe fruit centre stage; the only clue of the drawing's location is the curved bow of a gondola in the background.

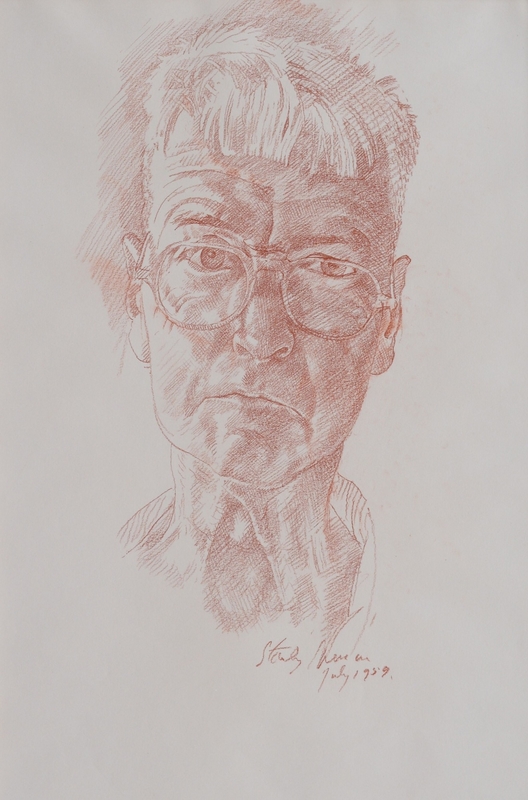

The British writer and artist Wyndham Lewis was invited to Venice by the heiress, writer, and political activist Nancy Cunard to draw her portrait in 1922. Through Lewis's eyes, Cunard is sketched standing as tall as the buildings in the background, her statuesque figure at once separate from and merging with the architecture of the floating city. Like the tower behind her, she stands straight, a hand balanced carefully on her hip, her composed contours an echo of her surroundings.

Yet Cunard's portrait was not the only drawing Wyndham would do in the city, as the title of Chapter VII in his autobiography Blasting & Bombardiering (1937) attests. 'A Duel of Draughtsmanship in post-war Venice' describes the moment when an Italian painter challenged him to a drawing competition: accepting, cheered on by the writers Osbert and Sacheverell Sitwell, Wyndham won.

Despite the frantic energy this image of drawing as a duel inspires, the irony is that the experience of drawing in Venice at most times implicitly requires one to stay still in a city that is restlessly moving, both through its crowds of people and also with the waters that overrun it. Lewis jokingly notes how he taught Richard 'Dick' Wyndham to sketch Venetian palaces: 'the fingers of one hand grasping the pencil and the fingers of the other grasping the nose, as all the best palaces are washed by cesspools.'

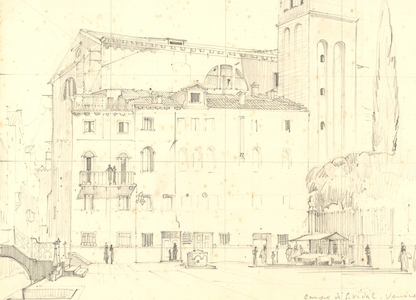

Image credit: Manchester Art Gallery

Façade of The Doge's Palace, Venice – Head of Adam (recto) c.1845

John Ruskin (1819–1900)

Manchester Art GalleryVenice is not easy to draw. Even Ruskin recalls how he 'vainly attempted to draw' the palazzo Ca' d'Oro in a letter to his father, bewailing how 'workmen were hammering it down before my face.' Yet the complexity and difficulties of drawing Venice make it such an alluring and enduring subject. It is a city that is constantly evolving. Its grand history, intricate architecture and absurd floating position can be overwhelming at times, but so too can the vitality and rawness of its day-to-day rhythm.

© the Eardley estate. All rights reserved, DACS 2025. Image credit: Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museums

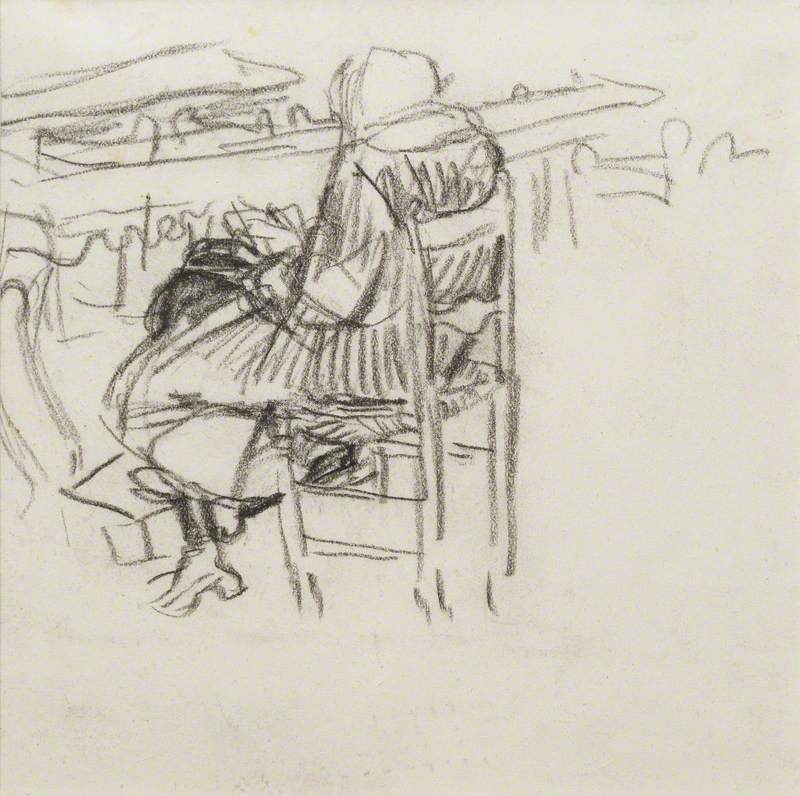

Woman in Pew Reading, San Marco, Venice 1948–1949

Joan Kathleen Harding Eardley (1921–1963)

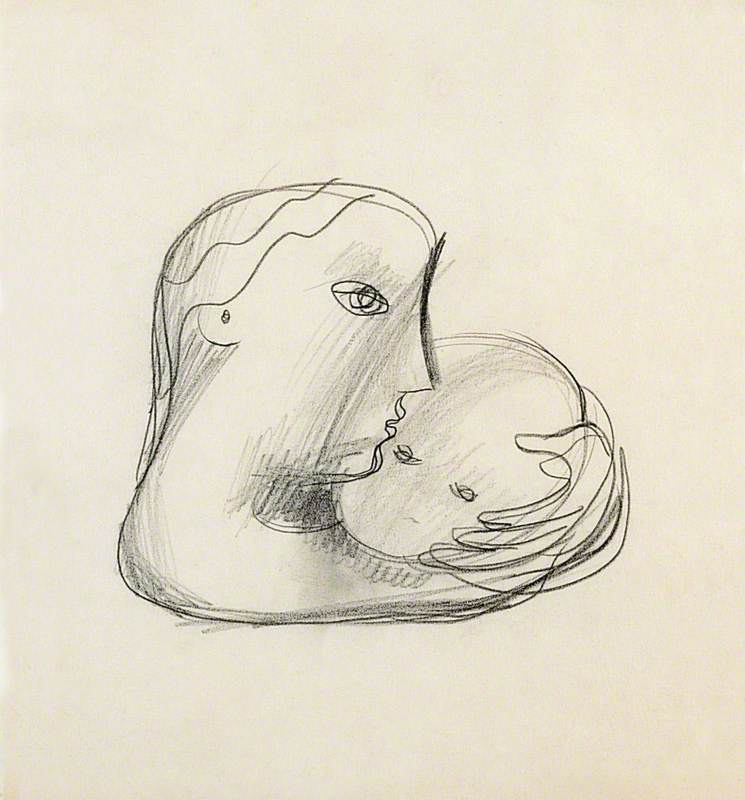

Aberdeen Art Gallery & MuseumsThe English artist Joan Kathleen Harding Eardley's drawing Woman in Pew Reading, San Marco, Venice could have been done yesterday. It's a subject as old as the stones of Venice: a woman enjoying a moment alone in her own company. Eardley would later become noted for her ability to capture the street life of Glasgow, where she lived and worked. She was famous in particular for her portraits of children in poverty. Before Scotland, it was in Venice where she noted the beggars on the street, taking them as her subject for some of the few paintings she produced from the trip. Her sketches take on similar themes, capturing the daily life of the city. Rather than the grandeur of the architecture, she focused on the quiet moments that continue to live within it.

© the Eardley estate. All rights reserved, DACS 2025. Image credit: Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museums

Fishing Nets at Burano, near Venice c.1949

Joan Kathleen Harding Eardley (1921–1963)

Aberdeen Art Gallery & MuseumsAfter all, in the end, this is Venice's true enduring fascination: it is a city that is still – against all odds – alive. It moves. It can be drawn through its stones or through its waters, rendered in stasis, in acute detail, with precision and architectural focus – or it can be all energy, spirited lines that sweep to and fro like the water lapping at the banks of its canals. It is a whirl of contradictions, but most strikingly it is a place, like drawing itself, where one must confront one's own reflection.

Thea Hawlin, writer, translator and cultural critic

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation