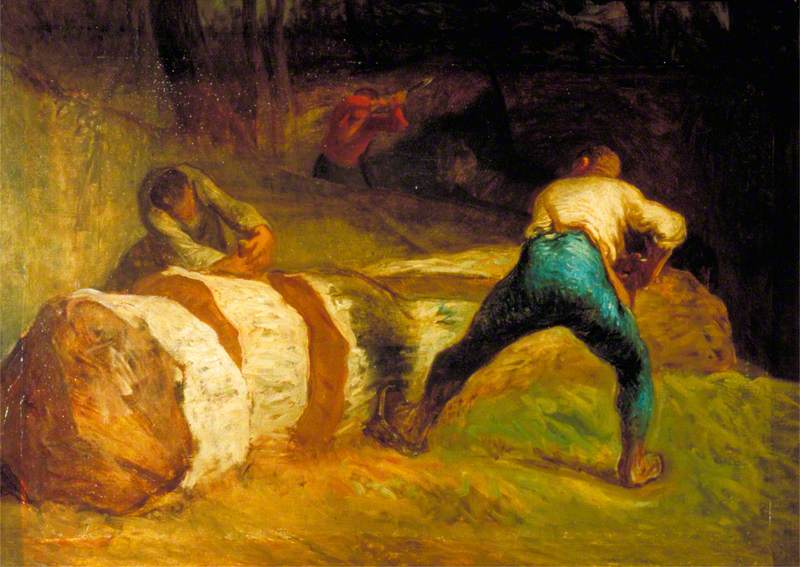

(b Gruchy, nr. Cherbourg, 4 Oct. 1814; d Barbizon, 20 Jan. 1875). French painter, draughtsman, and printmaker, born into a prosperous and cultured farming family in Normandy. After studying with local painters, he moved to Paris in 1837 and for two years continued his training under Delaroche at the École des Beaux-Arts. His early work consisted of portraits and then small mythological and pastoral scenes, but with The Winnower (NG, London), exhibited at the Salon in 1848, he turned to the pictures of rustic life from which his name is now inseparable. The Winnower perfectly caught the spirit of the time, for earlier in the year in which it was shown, King Louis Philippe had been deposed, helping to create a taste for pictures of ordinary people such as this (it was indeed bought by a minister in the new republican government).

Read more

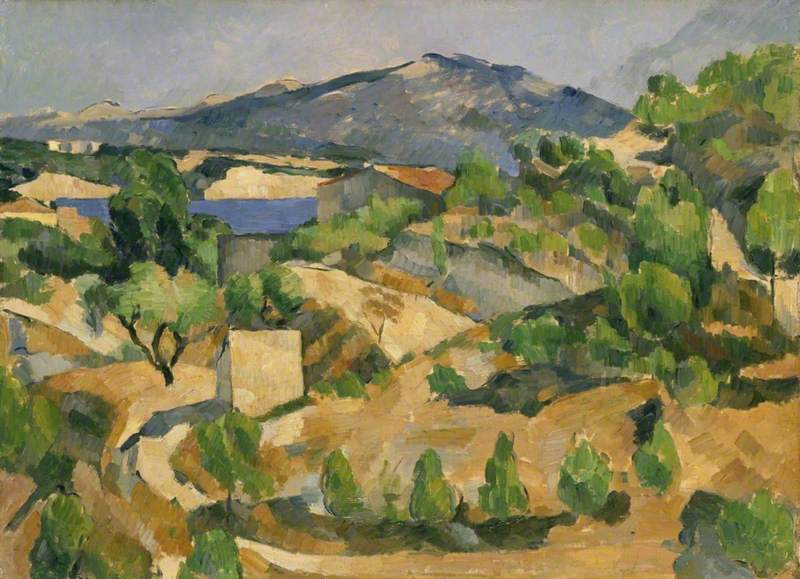

Critics of the time tended to interpret Millet's work in terms of their own social views: whereas republicans thought that he was showing the dignity of working people in a progressive spirit, conservatives regarded his paintings as coarse and subversive, the peasantry being to them a potential source of civil unrest. Millet himself, however, saw his work in aesthetic and personal rather than political terms, and the feeling of sad solemnity that so often characterizes it is an expression of his own melancholic temperament. In 1854 he commented: ‘I must confess, at the risk of being taken for a socialist, that it is the treatment of the human condition which touches me most in art…I never see the joyous side; I do not know where to find it, for I have never seen it. The happiest thing I know is the calm and the silence one so deliciously experiences in the forest or in the fields.’ This ‘calm and silence’ he expressed through figures of great strength and dignity, reflecting his admiration for Old Masters such as Poussin.In 1849 Millet settled at Barbizon, where he remained for the rest of his life apart from the period of the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1), when he took refuge in Cherbourg. Late in his career he turned increasingly to pure landscape, influenced by Théodore Rousseau, one of his closest friends. Rousseau sometimes helped Millet financially, for he spent much of his career in poverty, but in the 1860s—his work now being much less controversial—he began to prosper and to build an international reputation (he became especially popular with American collectors). By the time of his death he was an honoured figure (although still not financially secure—the ever-generous Corot supported his widow), and he had considerable influence on late 19th-century art. Seurat, for example, greatly admired the grand simplicity of his draughtsmanship, and van Gogh copied reproductions of his work when he was teaching himself to draw. As well as achieving great respect among fellow artists, Millet also pleased a large popular audience, above all with The Angelus (1859, Mus. d'Orsay, Paris), which became perhaps the most widely reproduced painting of the 19th century. This had a harmful effect on his subsequent critical fortunes, for largely on the strength of it he was pigeon-holed for much of the 20th century as a purveyor of pious sentimentality (it shows a farmer and his wife pausing in their work to pray as a church bell tolls the evening Angelus). A major exhibition of his work in Paris and London in 1975–6 was a landmark in his critical rehabilitation.

Text source: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford University Press)