(b Aberdeen, 19 Sept. 1806; d Streatham, Surrey [now in London], 14 Feb. 1864). Scottish painter, designer, and administrator, active mainly in London. In the 1820s he twice visited Italy, where he was influenced by Renaissance painting and by the Nazarenes, with whom he became friendly. Dyce was highly cultured and widely talented (he was an accomplished musician and wrote learned essays on antiquities and a prize-winning paper on electromagnetism), but initially he was successful mainly as a rather conventional portraitist in Edinburgh. In 1837 he moved to London to work for the newly founded Government School of Design (which developed into the Royal College of Art) and he made a tour of state art schools in France and Germany to study their methods.

Read more

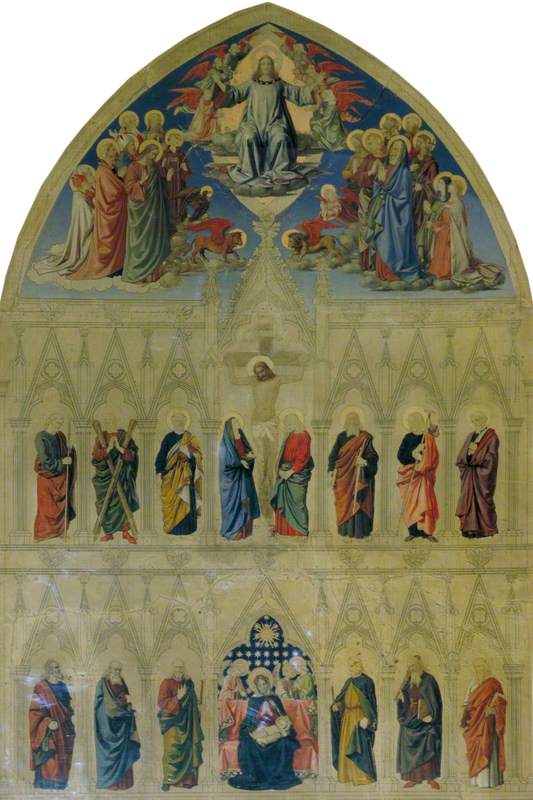

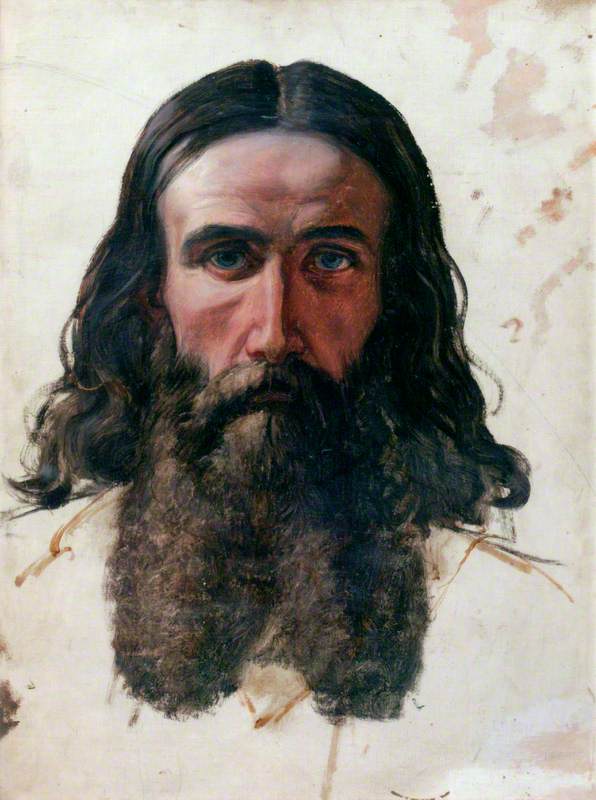

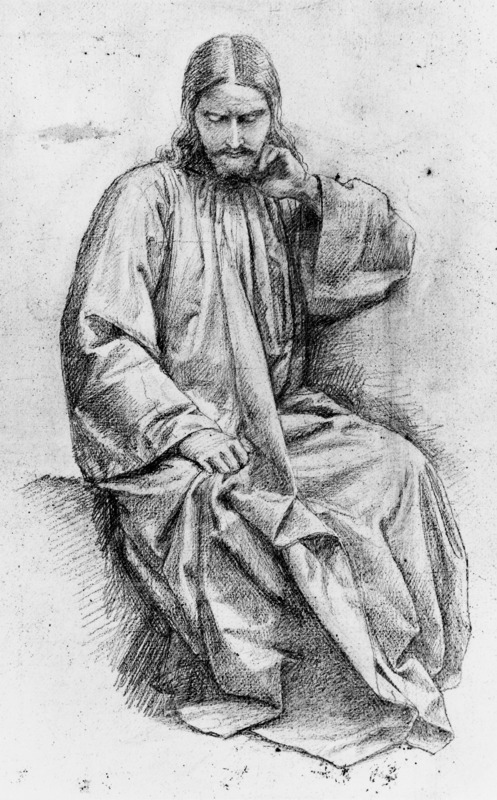

His report on his findings led to his appointment as superintendent (director) of the School in 1840. He resigned in 1843, but he remained a central figure in the art world—indeed ‘there was no major [artistic] undertaking in mid nineteenth-century Britain in which he did not play either an executive or advisory role’ (David and Francina Irwin, Scottish Painters at Home and Abroad, 1975). In particular he was a key figure in the revival of fresco painting, which was stimulated mainly by the mural decoration (begun 1843) of the new Houses of Parliament. Dyce's own work there has deteriorated badly, but his Neptune Resigning to Britannia the Empire of the Sea (1847, Osborne House, Isle of Wight) is one of the best preserved of all Victorian frescos. This was one of several royal commissions for Dyce, who was a favourite of Prince Albert. In addition to murals, he produced a varied range of easel paintings, from high-minded religious scenes (he was a devout Christian) to the delightfully sentimental Titian's First Essay in Colour (1856–7, Aberdeen AG); his Pegwell Bay, Kent (1859–60, Tate, London) is considered one of the most remarkable of all Victorian landscapes. Dyce's strong colours, firm outlines, naturalistic detail, and thoughtful sincerity of approach formed a bridge between the Nazarenes and the Pre-Raphaelites, and Ruskin said that it was Dyce who gave him his ‘real introduction’ to the Pre-Raphaelites when, at the 1850 Royal Academy exhibition, he ‘dragged me literally up to the Millais picture of the Carpenter's Shop, which I had passed disdainfully, and forced me to look for its merits’.

Text source: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford University Press)