There is no doubt that fashion exists in art. Just look at this painting of a barmaid at the Folies-Bergère, a little-known piece by some random painter...

A Bar at the Folies-Bergère

1882

Édouard Manet (1832–1883)

In truth, Edouard Manet's A Bar... is famed for the story it tells: it's a reportage of the social scene among Paris' nouveau riche, acting like a gossip as good as any that brims with nuanced j'accuse. Nineteenth-century artists relished the clash between the commercial revolution and the unflinching grip of morality, and as a result, implications were rife in their works.

But for the backstory and mastery of technique, there is one other element that is fetching about this well-known Folies-Bergère painting: the lady's style. Likely a uniform, it's interesting to see how much emphasis was placed on femininity – the corseted waist, the lace framing of her forearms and bust, the fashionable locket around her neck which draws the eyes towards her foliage-festooned chest.

Despite the notion of unhappiness we get from her expression, from which one might infer a sense of ennui and blasé continuity, she looks charming (particularly to the male customer glimpsed in the far right of the frame) because she is beautifully decorated. Fashion. The implied fact that she had no choice in the outfit, because it's a uniform, is by the by.

This is just one simple case in which one might wonder, en passant: what role does fashion play in empowering women – if at all?

Lovers of fashion would argue that it is an essential tool for navigating the nuanced complexities of day-to-day living. From workwear to daywear to evening attire, there seems to be a look for every occasion if you identify as female.

Au Bal – Marguerite de Conflans en toilette de bal

1870–1880

Édouard Manet (1832–1883)

The case is strong when one thinks of those instances when a woman prepares for a good time out, from a formal 'bal' to our modern-day hashtag FRIYAY moments. Style, through the carefully guarded medium of fashion, gives all an opportunity for self-expression and possibly projection to the wider world. We might think, for example, of terms like 'war paint' (makeup) and 'power suit' as indicators of sartorial protection. But from what are we trying to protect ourselves, exactly?

Others – 'haters', if you will – would argue that fashion has quite the opposite effect. They will point to the death toll resulting from the horrific Rana Plaza disaster – when a garment factory collapsed in Bangladesh –and third world exploitation, debates on fur and buzz words like anorexia, representation and objectification. There's a lot of negativity associated with fashion.

We know, too, that fashion facilitates our most narcissistic tendencies. From selfies to street-style, the shenanigans at the upcoming London Fashion Week will attest to this. But we can not merely point the finger at the fashionable glitterati – we are all culpable, if not in our obsessive participation, then in our innermost expectations when it comes to viewing others.

Giacinta Conti Cesi, formerly known as Hortense Mancini (1646–1699), Duchess of Mazarin

Jakob Ferdinand Voet (1639–c.1700) (after)

Indeed, when this portrait of a lady was being painted, the artist, model and commissioner were not focusing on the nuanced characteristics of that lady's personality. There has always been an emphasis on a woman's appearance and this visual emphasis is so often linked to her position in society. The better presented, the more agreeable the character.

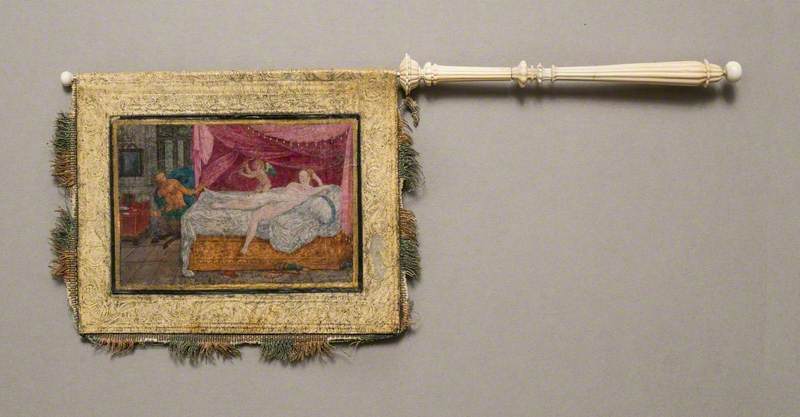

While I can understand why the Marquise of Belestat may have felt the need to be represented in all her feminine finery, what does this image described as a 'farm girl at her toilet lacing her corset' say about the subject's agency?

Farm Girl at Her Toilet, Lacing Her Corset

Eugène Modeste Edmond Lepoittevin (1806–1870)

Sure, the image is prettily depicted, but there is a lack of respect there, too. Perhaps it's the niggling sense that class factors into this fashionable portrayal of women at opposite ends of the social spectrum. This particular painting also highlights a converse point: the more 'deplorable' the character through a contemporary lens, the less favourably depicted by contemporary standards. And what is the marker of these characteristics? Fashion – festooned drapery for one lady, underwear for the other.

So which is it: friend or foe?

My guess is a bit of both, depending on the season. At the crux of this little musing is another niggling question: why are women often the ones tasked with the job of either deploring or defending fashion (a trope I am fully aware I am currently perpetuating)?

There is validity to posing the question as women are not the ones, broadly speaking, who dictate fashion's multi-billion-dollar industry. According to the findings from the 'Glass Runway' study (2018), the majority of leading fashion houses are helmed by men either in the atelier or the boardroom. This begs the question, why must women bear the responsibility of questioning fashion at all when they're not even the ones dressing themselves?

Patricia Yaker Ekall, journalist