To some art critics, the twentieth-century British artist William Scott's kitchen-table still lifes are too timid – as Roberta Smith wrote in The New York Times, they can be seen as 'abstract paintings for people who don't like abstraction'. Others, myself included, find them enticingly reduced and for the most part easily readable, which is part of their charm.

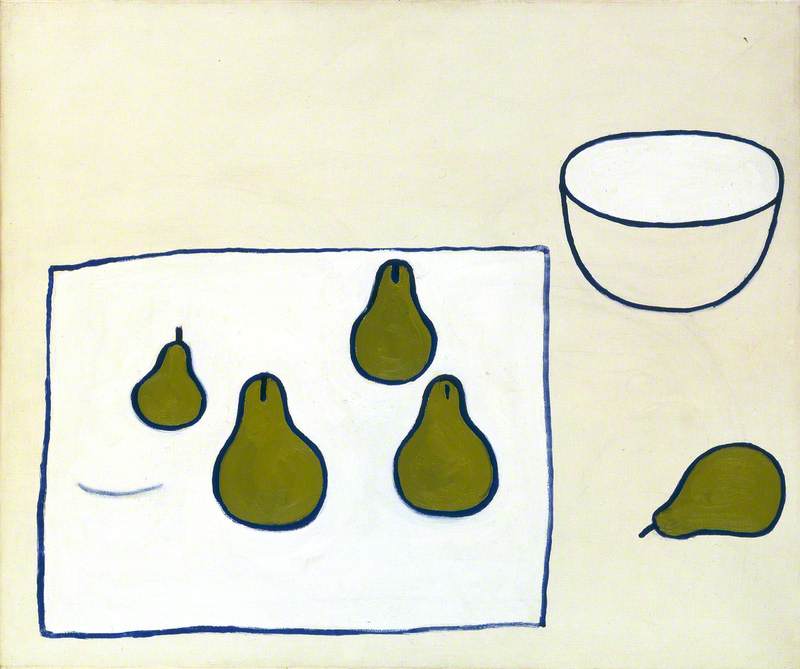

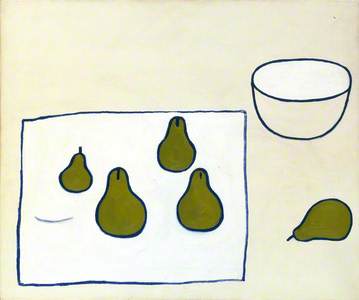

Scott's compositions are striking in their simplicity, and somehow both pleasurable and puritan, sensuous and serene. A few boiled eggs, a couple of ripe pears, fresh mackerel on a plate, pots and pans, a bunch of grapes: these are his humble subjects. As he once said, 'I find beauty in plainness'.

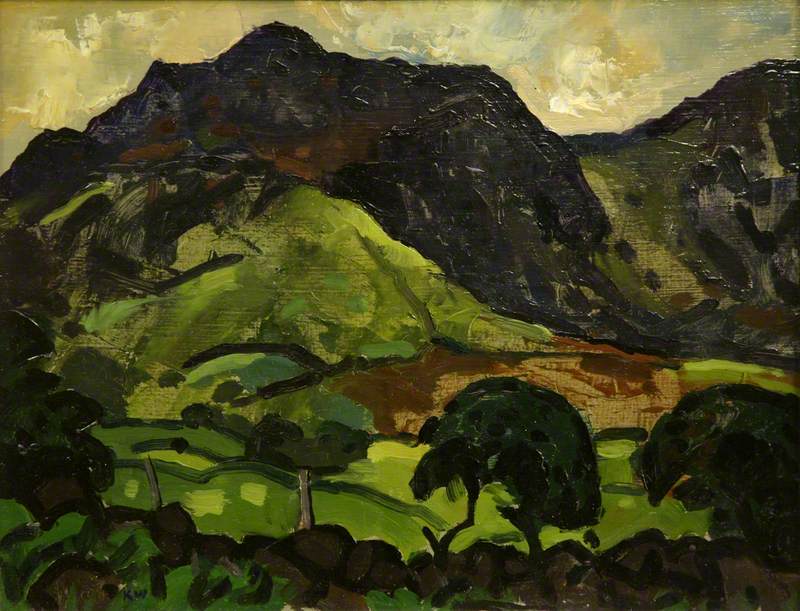

Born in Scotland in 1913 and brought up in Northern Ireland, Scott's surroundings were grey and barren, his upbringing strictly Presbyterian. The objects he painted in an often-sombre palette were, he said, 'the symbols of the life I knew best'.

After his father died trying to save some folk from a burning building, the local council raised funds to send the 15-year-old to Belfast College of Art. From there, he won a scholarship to study at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, where he bunked up with the poet Dylan Thomas and two other Welshmen and married fellow student Mary Lucas. In the Second World War, he was a cartographer, and in its wake, he was a pioneer of British abstraction.

Scott painted landscapes and nudes, with varying degrees of contouring, but his kitchen table still lifes are his trademark. He thought of The Frying Pan (1946) as something of a turning point. The titular pan has been placed on a folded white cloth along with a small bowl – its exterior eggshell, its interior crimson – and a four-pronged toasting fork.

The composition is austere, the paint surface rich: the brushstrokes on the golden-brown backdrop and the foggy silhouette of the cup are skittish. Just as he preferred his utensils to be fuss-free, Scott often rendered them roughly in paint – and they stick with us longer because of it.

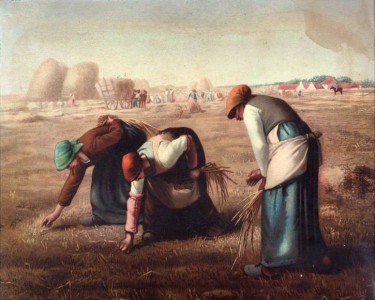

He was influenced by the still lifes of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, Pierre Bonnard and Georges Braque – 'If the guitar was to Braque his Madonna', Scott decided, 'the frying pan could be my guitar'. He was close friends with the artists of the St Ives School, with whom he spent long summers in Cornwall, though he didn't share their dedication to the pale cliffs and windswept harbours. There's joy in his work from the late 1940s, perhaps the result of a shared passion for painting, as well as shared ideas: the bright-yellow lemons and stark-white napkin pop against an otherwise shady setting in Still Life: Lemons on a Plate (1948), and the beady-eyed fish in Fish, Mushrooms, Knife and Lemons (1949 or 1950) appear to be swimming.

© estate of William Scott 2025. Image credit: Bristol Museums, Galleries & Archives

Fish, Mushrooms, Knife and Lemons 1949 or 1950

William Scott (1913–1989)

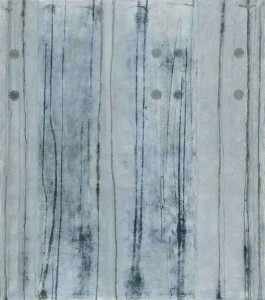

Bristol Museums, Galleries & ArchivesCreated over a 60-year career, Scott's paintings flit between figurative and abstract; the sizes vary, as do the finishes. Inspired by Ben Nicholson, for a while he aligned himself more firmly with abstraction, reducing his tabletops to flat rectangles of colour. Table Still Life (1951) could be a floorplan for all its lack of depth. It's more about the division of space – with the spindly white table legs slicing through the black ground – than the representation of it. The painterly objects on the table, which include a deep-blue bottle and a pebble-grey pan, press towards the picture plane.

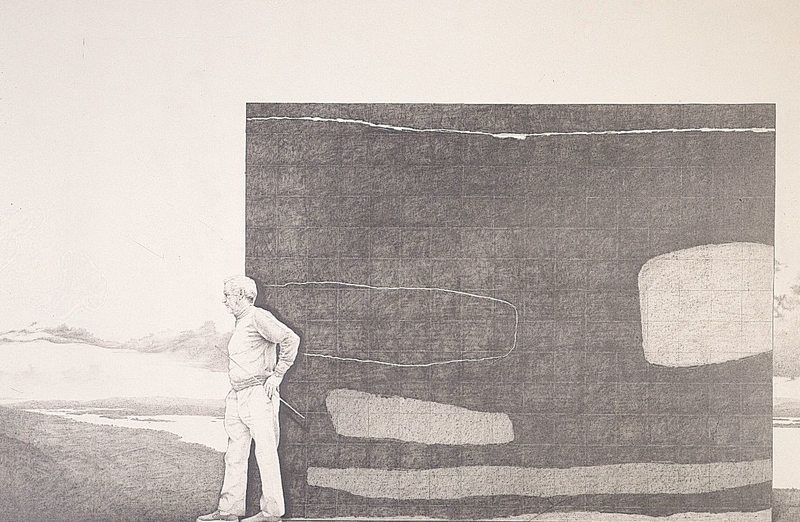

© James Scott. Image credit: Courtesy of William Scott Foundation

William Scott and Mark Rothko, Somerset

1959, photograph by James Scott (b.1941)

In 1953, he visited the US and came face to face with the colour-field paintings of Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. Rothko and Scott hit it off, and six years later the late great Abstract Expressionist visited Somerset – as documented in a black-and-white photograph taken by Scott's son, James.

Once he'd soaked up the more monumental and impulsive style of the New York School, his paintings grew bigger and bolder. In Orange and Blue (1957), distorted shapes float through a tangerine vacuum that calls to mind Rothko's more exuberant canvases. 'My pictures now contained not only recognisable imagery but textures and a freedom to distort', he said.

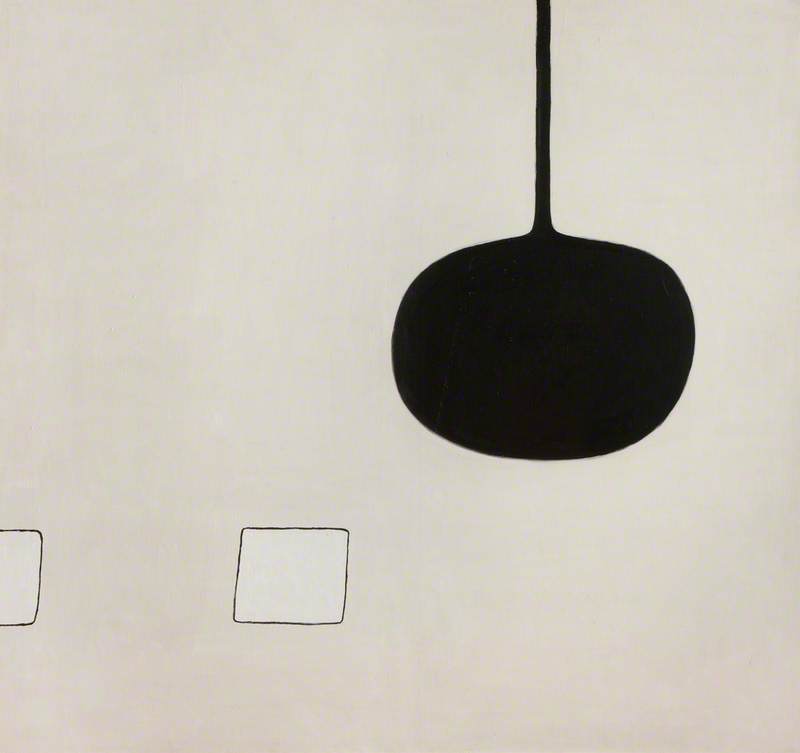

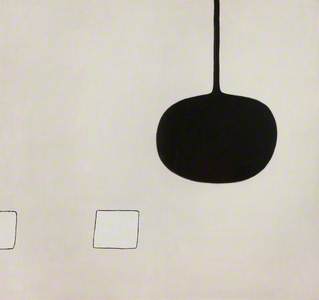

The result of all these influences was a style that was entirely Scott's own, and that blended the traditions of European art with the vanguard of twentieth-century America: he dubbed it 'primitive realism'. That style became more minimalist in the 1960s and 1970s. In White Shapes Entering (1973), empty space dominates; the creamy ground is interrupted only by a pancake-flat pan and two squared-off cups, whose dark outlines emphasise their sense of containment. Five Pears (1976) is entirely devoid of depth: the shapely pieces of fruit could slip straight off the white cloth and land at your feet.

'I like primitive art and children's art and the things that children scratch on walls and draw on pavements', said Scott, who was also fond of 'the beauty of the thing being badly done'. Some critics were less keen on his later work, regarding it as too simple, too absent. But it's in that absence that we find room to imagine.

Take Six Open Forms (1971): consider the relationship between the widely spaced shapes, as well as their relationship with the patch of colour they inhabit. There's a musicality to the carefully choreographed canvas; as in a melody, there's a succession of tones – in this case, shades of cream – that come together to form a whole.

Scott's heyday was in the 1950s. His exhibition at London's Hanover Gallery in 1953 was seen by directors at the Guggenheim and MoMA, who went on to sing his praises in the US. In 1958, he was the UK's chief representative at the Venice Biennale. In 1961, David Sylvester said that he had gained 'the soundest, all-roundest international reputation of any living British painter, Nicholson apart', and in 1973 Hilton Kramer called him 'the best painter of his generation in England'. But with the arrival of Pop Art, he fell from favour – until the 2000s, when twentieth-century British art began to gain in popularity.

And what a relief, because there's so much pleasure to be gained from looking at Scott's art, spartan as it is. He took the ordinary and made it extraordinary.

Like any good designer, he understood the power of well-placed white space – it's there, as in a well-timed pause, that we have time and space to feel. And feel you will. Because empty as Scott's paintings may seem, each is invested with emotion. That, and a lingering human presence – in a snuffed candle, a simmering pan, a sliced lemon.

Chloë Ashby, freelance writer and editor

![[Still Life: Lemons on a Plate]](https://d3d00swyhr67nd.cloudfront.net/w800h800/collection/NGS/NGS/NGS_NGS_GMA_2066-001.jpg)