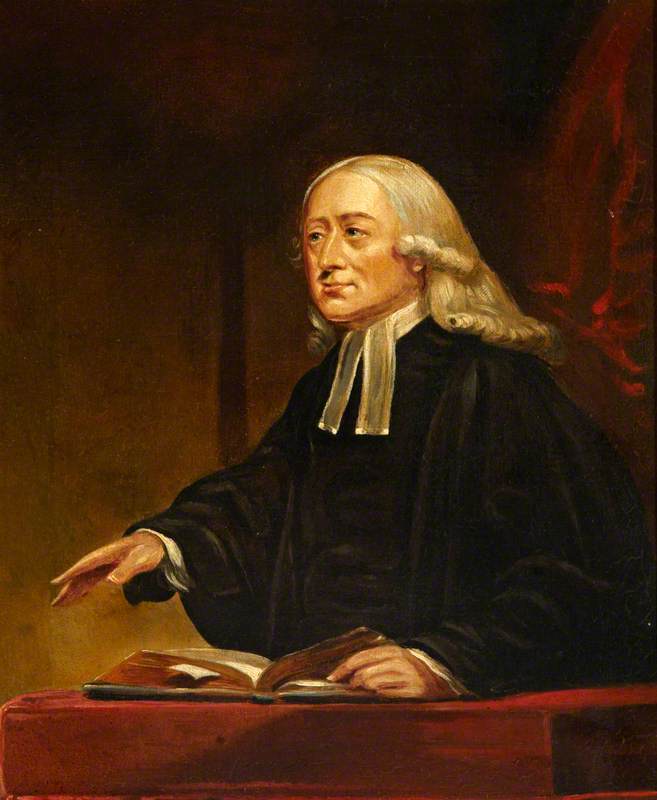

A Church of England clergyman, John Wesley (1703–1791) is often labelled the 'Founder of Methodism'.

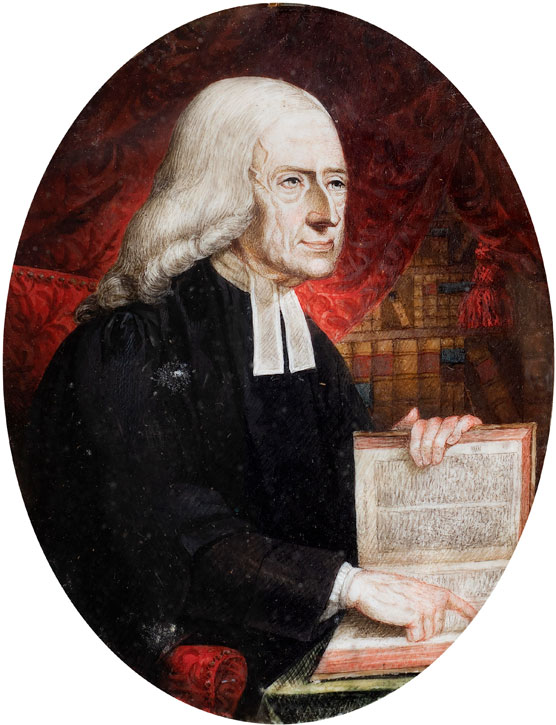

John Wesley

1790, oil on ivory attributed to John Barry (active c.1784–1827). Although signed 'Arnold', an attribution to the miniature artist John Barry seems likely, in which case this was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1790

But he did not set out to start a new denomination. Rather he established an organisation of religious 'societies' within the national church, though it was almost inevitable that after his death these would separate from it.

The son of the Rector of Epworth parish in Lincolnshire, Reverend Samuel Wesley (1662–1735), he was particularly close to his mother Susanna (1669–1742). After school at the Charterhouse, London, he studied at Oxford University's Christ Church between 1720 and 1724. He was elected a Fellow of Lincoln College, Oxford, in 1726; and was also ordained (deacon 1725, priest 1728), spending much of 1727–1729 helping in his father's parish.

Meanwhile, his younger brother Charles (1707–1788), then taking his degree at Oxford (also at Christ Church), had joined with friends to form a group of religious enthusiasts which became called (among other derogatory terms) as 'Holy Club' or 'Methodists'. On his return to Oxford, John Wesley became its main leader.

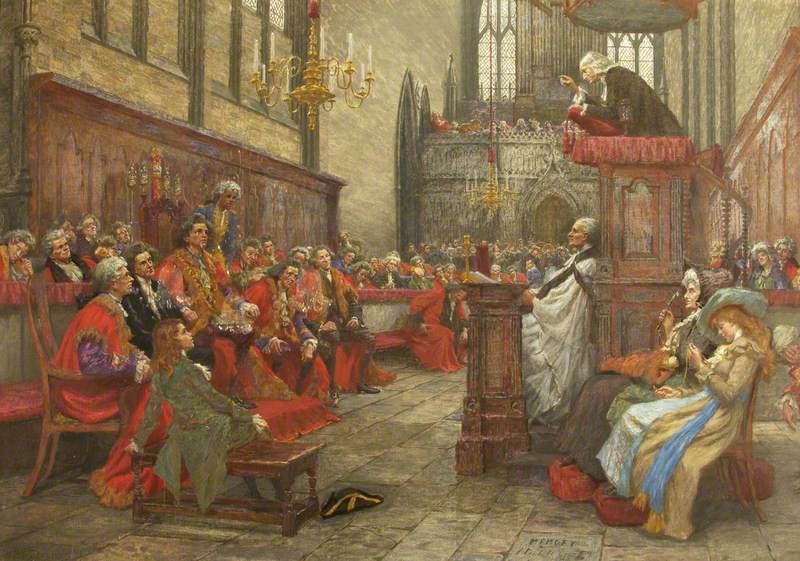

John Wesley and His Friends at Oxford

1858

Marshall Claxton (1813–1881)

Both Wesleys went to America in 1735, to the new colony of Savannah, Georgia, but they returned to Britain disappointed. In May 1738, both had an evangelical experience: the following year, John (encouraged by George Whitefield (1715–1770), who had been among the Oxford 'Methodists') started preaching in the open air, flouting church laws and also the bounds (and jurisdiction) of parishes.

For the next 50 years, John Wesley travelled throughout Britain and Ireland, mostly preaching several times each day, often in the open air, but – more significantly – forming small groups ('Methodist societies') which he linked together in local 'circuits'. In 1744 he met with a group of key leaders, the first of what became the annual 'conference' which governed the movement.

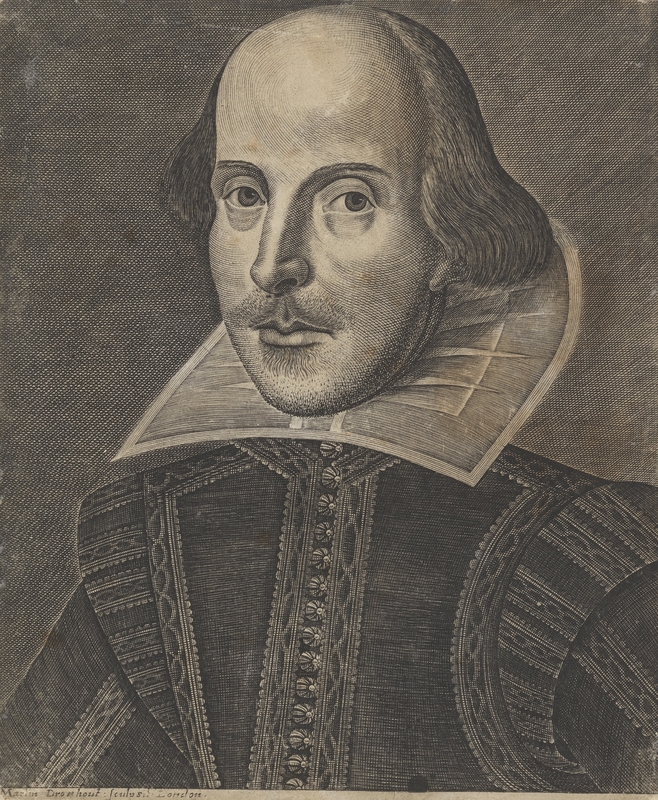

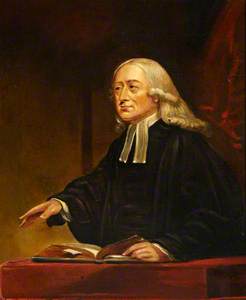

The first confirmed portrait of Wesley was made around this time: in September 1743 the London engraver Johannes Faber advertised a mezzotint print of Wesley, after the picture by John Michael Williams. At a time when Wesley was attracting much criticism for his religious 'enthusiasm', unseemly for a clergyman and an Oxford don, he was painted in clerical and academic gowns, surrounded by (mostly religious) books, emphasising his establishment credentials.

Around 1760 Wesley's 'connexion' (as the movement was becoming termed) became more formalised, and started building preaching houses for societies. There were already buildings in London (a former cannon factory – The Foundry in Moorfields), Bristol (a purpose-built multi-functional meeting room with accommodation above), and Newcastle upon Tyne (called the Orphan House, but in reality more a residential centre). Wesley was keen that Methodist buildings should not be licensed as 'preaching houses', which would suggest they were independent of the Church of England, which he always insisted was not the case. His groups were required to attend services in their local parish churches, and take communion when possible.

Wesley was an incessant writer, penning thousands of letters. He kept a detailed diary (in shorthand), which he wrote up and published as his Journal. He wrote or edited some 400 titles, making him probably the most prolific author of the eighteenth century. Many of these were hymnbooks: his brother Charles wrote around 7,000–9,000 religious verses, of which some 2,000 were used as hymns. These included 'Hark, the Herald-angels sing', 'Love Divine, all loves excelling', 'Hail the day that sees Him rise' and many others still sung today, well beyond the bounds of Methodism.

Reverend Charles Wesley (1707–1788), MA

1771

John Russell (1745–1806)

The vast majority of portraits of John Wesley were taken in the last decade of his life, when he was in his 80s, though still active.

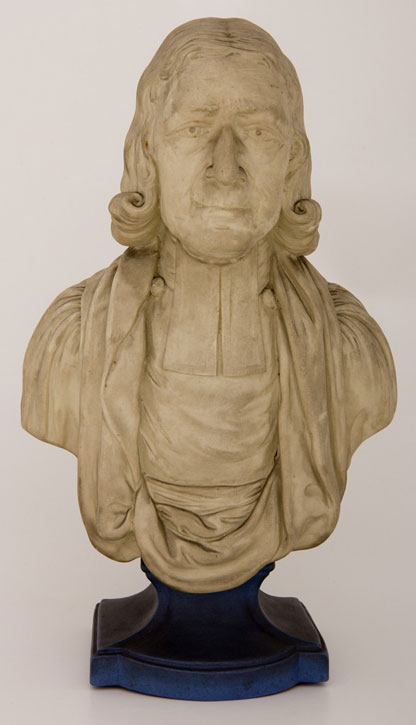

The Reverend John Wesley (1703–1791)

after 1791, white biscuit sculpture by Enoch Wood (1759–1840)

The 1781/1784 bust by the Staffordshire potter Enoch Wood was reckoned to be the best likeness of him.

In 1789 the leading portrait painter George Romney showed him as a man who seemed to have aged little over the years.

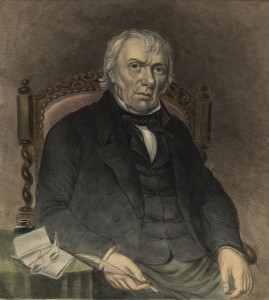

John Wesley (1703–1791)

(after George Romney)

Kate Gray (1840–1918)

This painting after Romney is one of two portraits of Wesley known by a woman artist – Kate Gray was Charles Wesley's great-granddaughter.

A miniature of a year later shows a face which has all the marks of age; by then Wesley was nearly blind.

John Wesley

1790, oil on ivory attributed to John Barry (active c.1784–1827). Although signed 'Arnold', an attribution to the miniature artist John Barry seems likely, in which case this was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1790

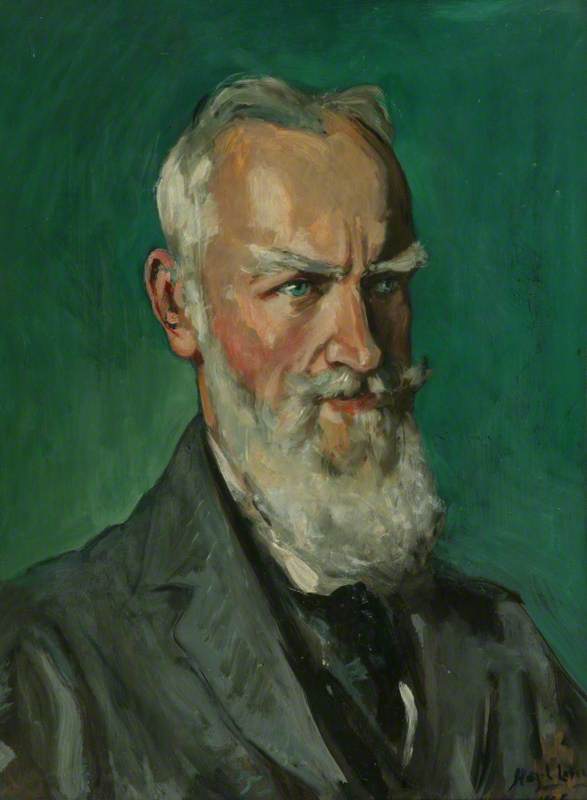

After Wesley's death in March 1791, portraits of him continued to appear but the likeness started to become less realistic. By the 1820s the Wesleyan Methodists (as they had then become) decided to produce a 'standard' image, by John Jackson – a leading portrait painter who was also a Wesleyan – as the frontispiece for a new edition of the hymnbook.

However, this was soon criticised by people who remembered Wesley as not being like him. Nevertheless, millions of prints were made over the years, and numbers of painted copies exist.

In the twentieth century, portraits of Wesley were still painted: the society artist Frank Salisbury (done around the time the various British Methodist denominations reunited in 1932) showed a statuesque larger than life John Wesley, hardly the slight, 5 foot 3 inches energetic man he was.

John Wesley (1703–1791), as an Old Man

1932

Frank O. Salisbury (1874–1962)

During the nineteenth century, artists started painting scenes from Wesley's life. The first was from Ireland, in a recreated scene, surrounded by the artist's children, born long after Wesley's death!

John Wesley Preaching in Ireland, 1789

early 19th C

Maria Spilsbury (1777–1820) (attributed to)

Often these were intended for public exhibition, such as Henry Perlee Parker's depiction of the rescue of John Wesley (then five years old) from the fire which destroyed his childhood home.

The previous year Parker had painted another heroic rescue: Grace Darling rowing out to rescue the crew of the Forfarshire, which was iconic for the growing lifeboat movement.

William and Grace Darling Going to the Rescue of the SS 'Forfarshire'

1838 (?)

Henry Perlee Parker (1795–1873)

John Wesley's dramatised deathbed scene was painted in 1842 by another Methodist artist, Marshall Claxton.

The Holy Triumph of John Wesley in His Dying

c.1842

Marshall Claxton (1813–1881)

Wesley actually died in a small room in his home in London: Claxton depicted all those recorded as visiting the dying man in the last day or two of his life. Both Claxton and Parker made dramatic use of light and composition in these large pictures.

John Wesley Preaching from His Father's Tomb at Epworth

c.1859–1860

George Washington Brownlow (1835–1876)

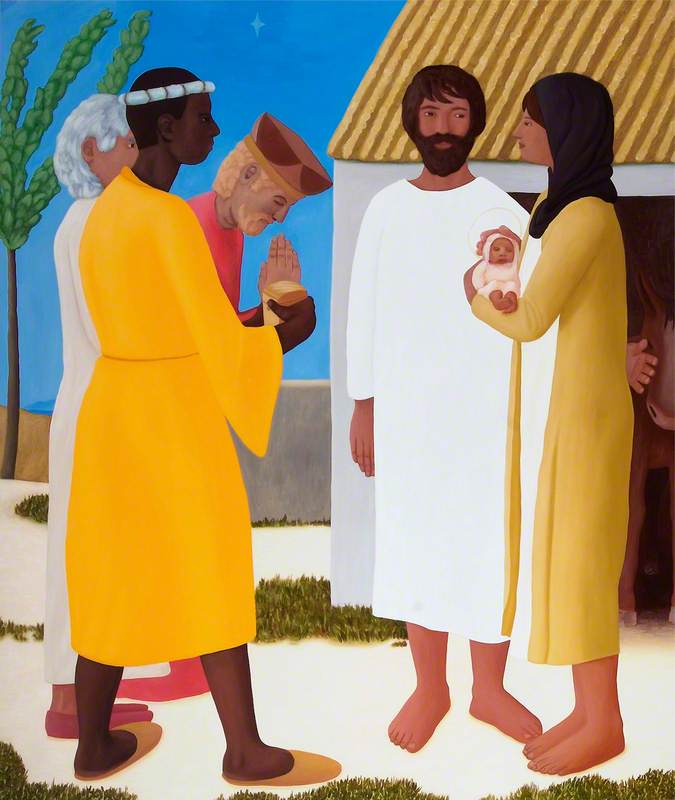

They fostered an image of John Wesley more legendary than lifelike which continued in other 'scene paintings' such as preaching from his father's tomb or before the Lord Mayor and Corporation of Bristol.

John Wesley Preaching before the Mayor and Corporation of Bristol, 1788

1918

William Holt Yates Titcomb (1858–1930)

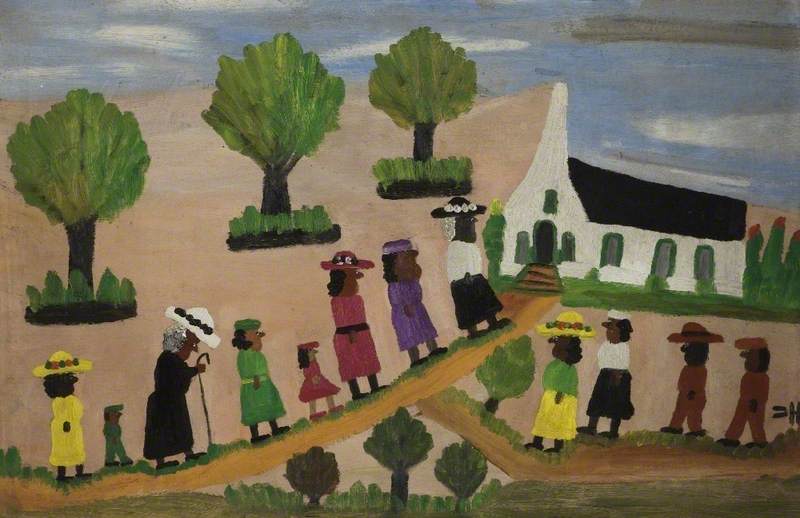

The Methodist family of churches now counts a membership of over 50 million globally, for whom the life, writings and example of John Wesley, and Charles Wesley's hymns, remain formative. His image is central to this consciousness, and is recognised beyond the bounds of the church – from postage stamps to prints and oil paintings to sculpture.

Peter Forsaith, Research Fellow of the Oxford Centre for Methodism and Church History at Oxford Brookes University