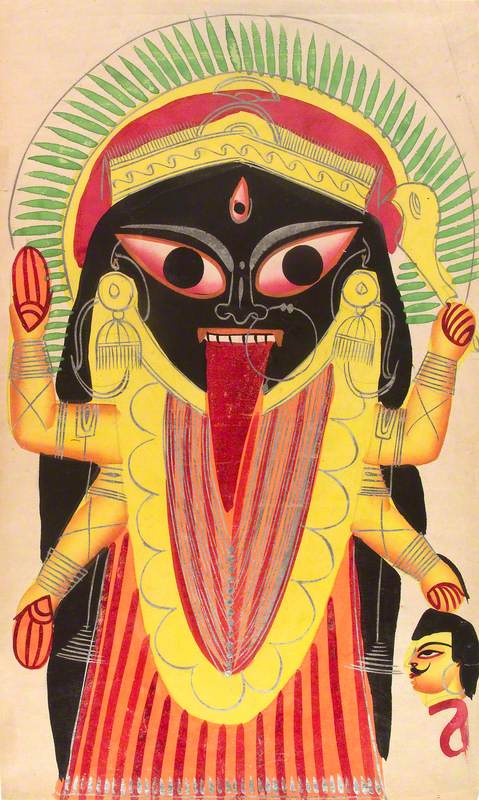

In the early 1800s, Katsushika Hokusai created a series of woodblock prints of Mount Fuji, including the now-iconic Great Wave. He may have dreamed of his work one day travelling across Japan's borders and gaining global recognition. Yet he never could have realised the impact his prints – and the prints of his contemporaries – would have on a group of artists living and working in Paris at the end of the nineteenth century.

Under the Wave off Kanagawa, or The Great Wave

Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

The Japanese 'artists of the floating world' and the French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists they influenced lived tens of years and thousands of miles apart, but they had an artistic connection: the desire to paint and glorify real life scenes. Both groups wanted to recreate what they saw all around them in all of its romantic, mundane or sometimes sordid nature.

Japanese artists tackled this through 'ukiyo-e' woodblock prints, which, while created primarily for commercial use (they were both popular and cheap), were highly original in their use of colour and composition, and contained radical elements which entranced the French artists looking to break away from tradition. They played with bright colour and flattened perspectives, sometimes leaving the middle ground of a painting empty, sometimes artificially compressing compositions and cropping figures. They showed the French artists a radically different way their art could be.

Geisha Walking through the Snow at Night

c.1797, polychrome woodblock print, ink & colour on paper by Kitagawa Utamaro (c.1754–1806)

For 200 years, Japan had been an intentionally isolated nation, accessible only to a small number of Dutch traders via the island port of Dejima. In 1853, just four years after Hokusai's death, Japan started to reopen to the rest of the world, and its art and artifacts began to make their way around the globe – and into the hands of artists open to being inspired and influenced. When the Floating World arrived in Paris, it was perfectly timed to give the Impressionists and post-Impressionists a template to create the work they desired.

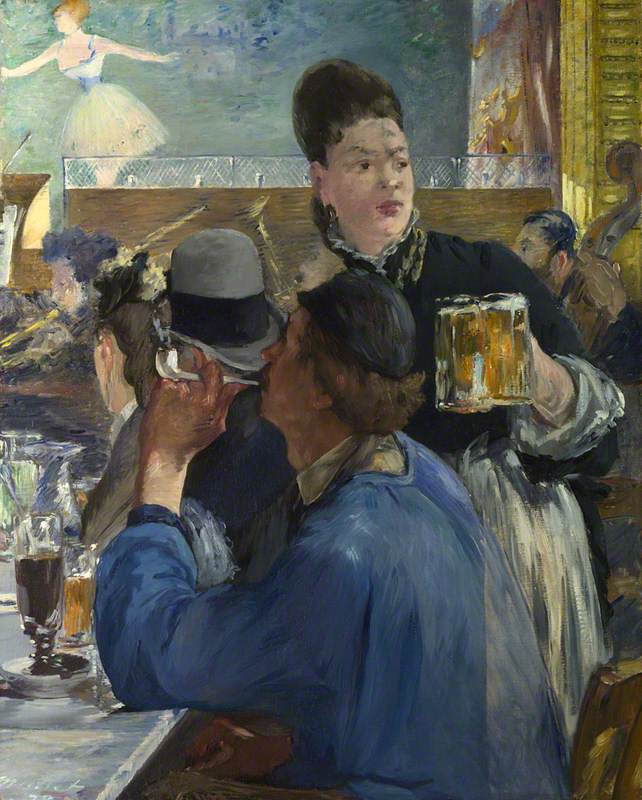

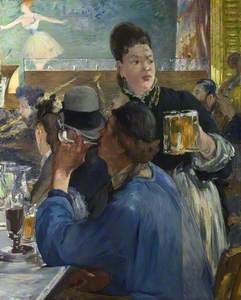

Édouard Manet

Manet, the father to the Impressionists, was the first major painter to create artworks in response to ukiyo-e prints. Keen to break with tradition and yet still represent the here and now of daily life in Paris, the prints he saw from Japan showed him how this could be achieved. They gave Manet permission to do away with perspective, to use flat colours instead of careful light and shade, yet still represent his subjects with all-important authenticity.

Manet's works, with their learned flatness of colour and static style, mark the start of artists considering their own takes on ukiyo-e art. Manet began to bring to life the 'floating world' of Paris – the bars, the cafes, and the people who frequented them – much as Japanese artists had captured the floating world of Edo (Tokyo) before him.

Vincent van Gogh

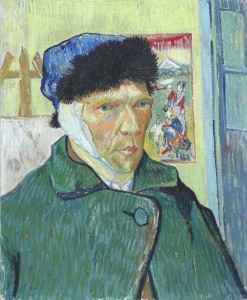

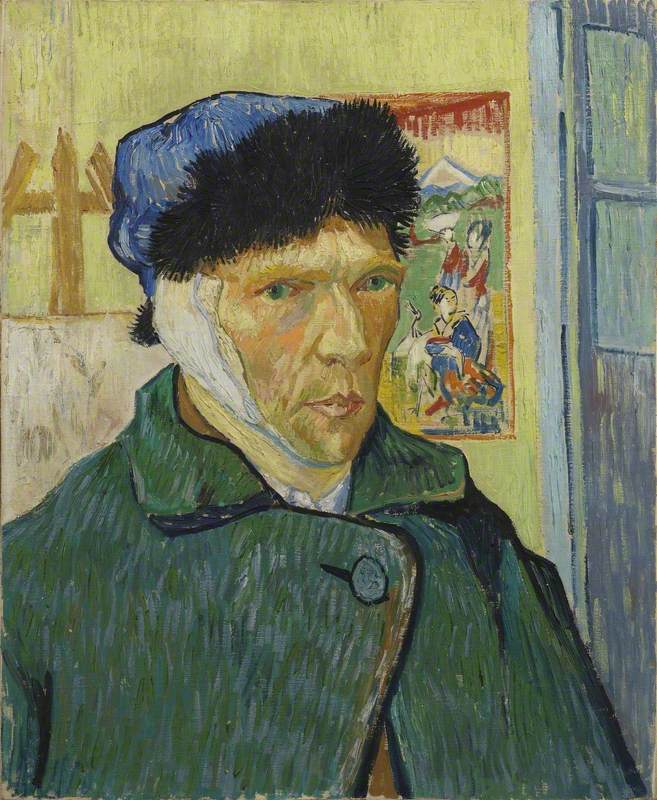

Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear

1889

Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890)

Van Gogh was certainly not the first to fall under the spell of Japanese art, but he eventually embraced it so eagerly that he and his brother, Theo, amassed a collection of hundreds of ukiyo-e woodblocks – now held by the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. The self-portrait above, with a prominent Japanese print, shows that he was thinking of Japan even when absorbed in himself as a subject.

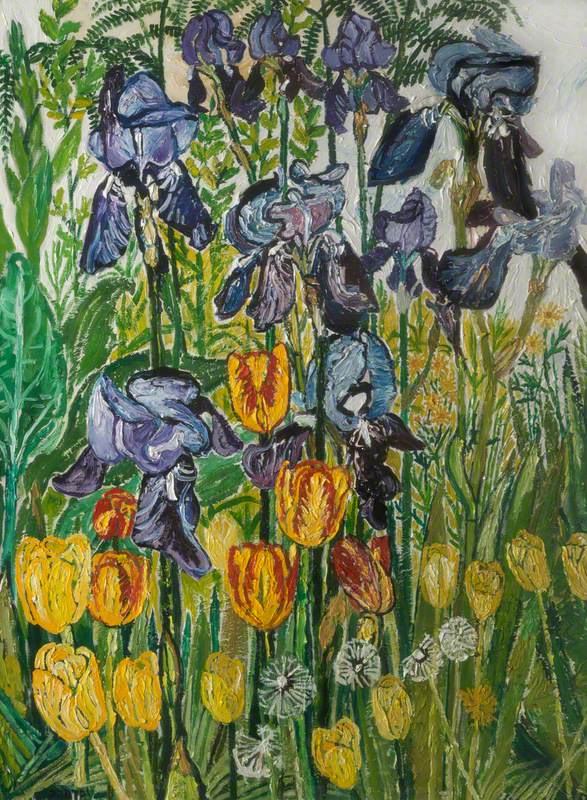

When he first came across Japanese prints, Van Gogh was inspired to make several direct copies – including his Bridge in the Rain (after Hiroshige) – before allowing the influence of ukiyo-e to take centre stage in his original works. He began to play with depth and perspective, combining the flatness from Japanese prints with his swirling brushwork, and making use of smooth black outlines: all of which can be seen in this portrait, La Berceuse.

La Berceuse (Woman Rocking a Cradle; Augustine-Alix Pellicot Roulin, 1851–1930)

Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890)

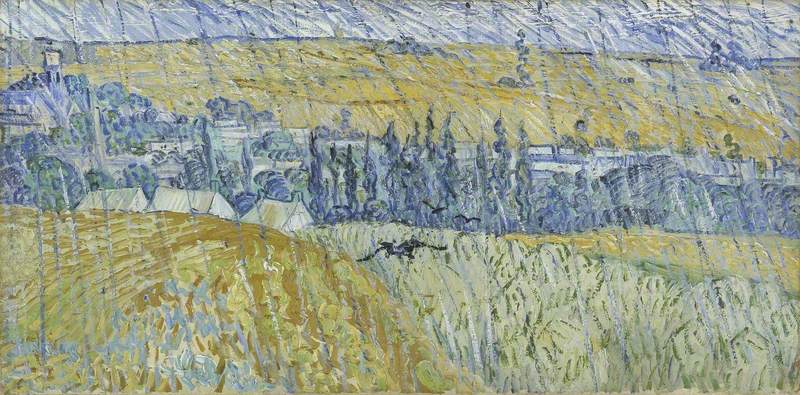

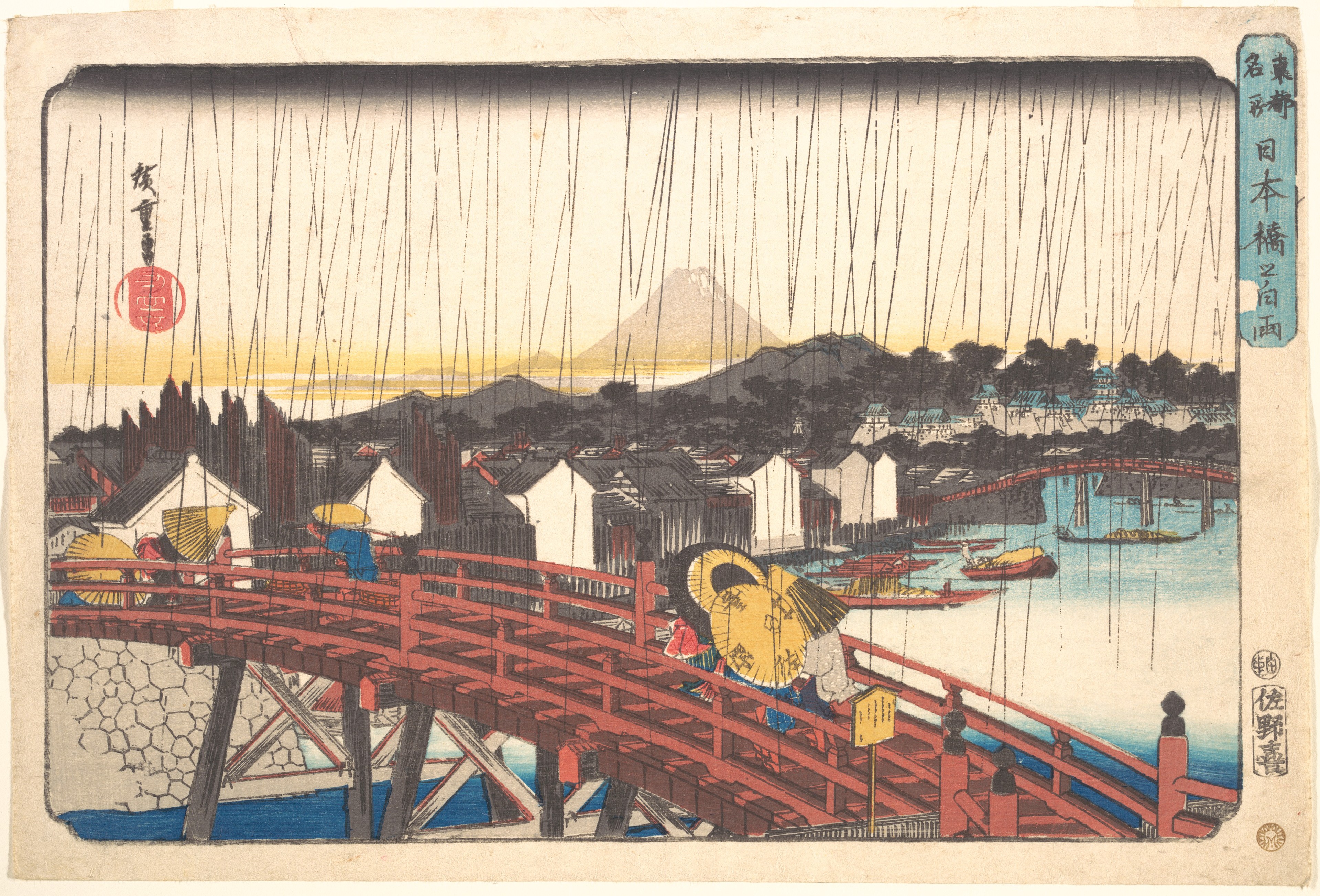

This newfound influence is front and centre in Rain, Auvers. As described by Axel Rüger, director of the Van Gogh Museum, for Art UK: 'The most striking features of the painting... are the thin strokes that cut across the picture in vertical lines, representing the pouring rain. With this motif Van Gogh reaches back to Hiroshige's famous woodcut print of the Bridge in the Rain.'

Sunshower at Nihonbashi

Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858)

'Japonisme' was a term coined to describe the craze for Japanese prints among Western artists, though Van Gogh himself used the term 'Japonaiserie'. In letters to his brother, dated towards the end of his life, the artist wrote:

'All my work is based to some extent on Japanese art... Japanese art, in decline in its own country, is taking new roots among French Impressionist artists.'

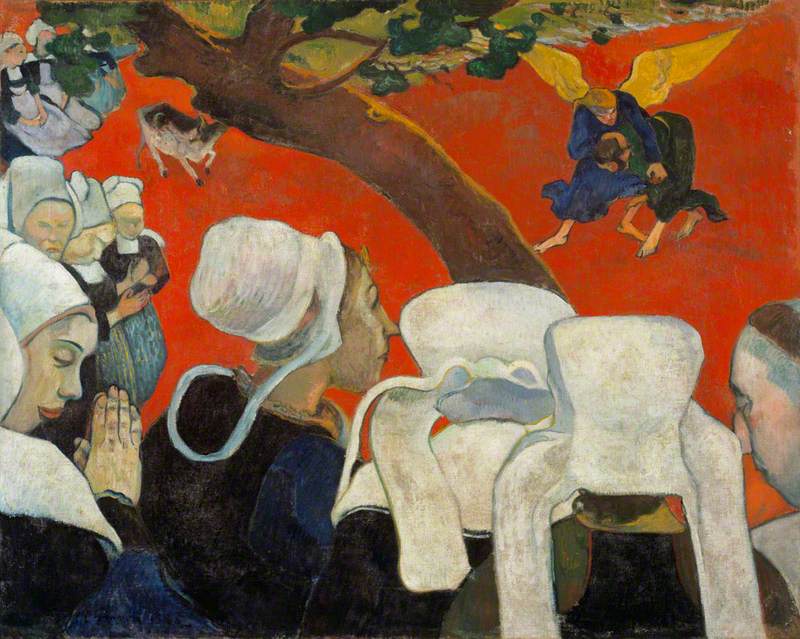

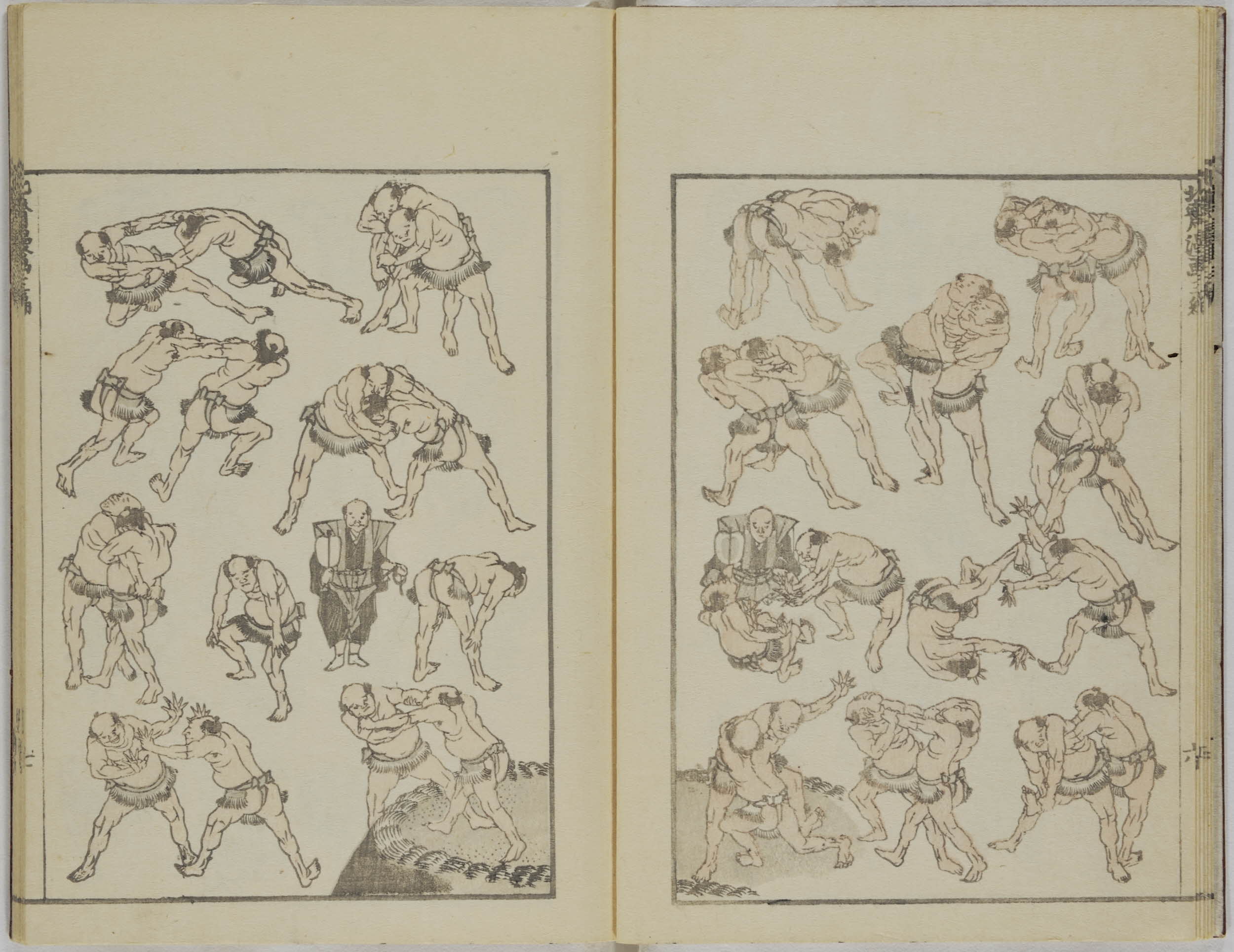

Van Gogh's contemporary and friend Paul Gauguin also fell under the spell of Japonisme. The painting below, with its swathes of bold colour and flattened perspective, marks the point at which Gauguin started to look towards Japan for influence, with the wrestling Jacob and angel figures taken from Hokusai's manga.

Vision of the Sermon (Jacob Wrestling with the Angel)

1888

Paul Gauguin (1848–1903)

Page from Hokusai's 'Manga'

Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Edgar Degas

He's famous for his representations of dancers and the moving form: but Degas, along with his friend James Tissot, were also among the earliest collectors of Japanese art in France. As put by writer Colta Feller Ives:

'Degas made no secret of his admiration for Japanese prints... when his personal print collection was sold in 1918, it included over a hundred Japanese woodcuts and albums by Utamaro, Hokusai, Horoshige, Kiyonaga, Toyokuni, and other ukiyo-e masters... he shared with the ukiyo-e masters a heightened awareness of the world about him, an eye for the unusual in the everyday, the remarkable in the ordinary, the timeless in the momentary.'

The greatest Japanese influences on Degas' art can be seen in his fascination with intimate female scenes (one colourful example is Combing the Hair in The National Gallery, and his composition.

In his paintings, figures are often placed to one side of the artwork, leaving empty space, rendered in blocks of colour, in the centre. In some, the figures are cropped almost cruelly.

We can only see half of the girl at the right hand side, and the spiral staircase restricts the view of the figures on the left: composition learned from ukiyo-e.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Degas had set the scene for making works inspired by Japanese art: and Toulouse-Lautrec, in turn, was inspired by Degas. Toulouse-Lautrec is a well-known figure from the Belle Époque, featuring in films such as Baz Luhrmann's Moulin Rouge, and he too created paintings depicting modern subjects, like music halls, bars and brothels: his artworks are a catalogue of decadent, absinthe-soaked Montmartre party life.

In a Private Dining Room at the Rat Mort

c.1899

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901)

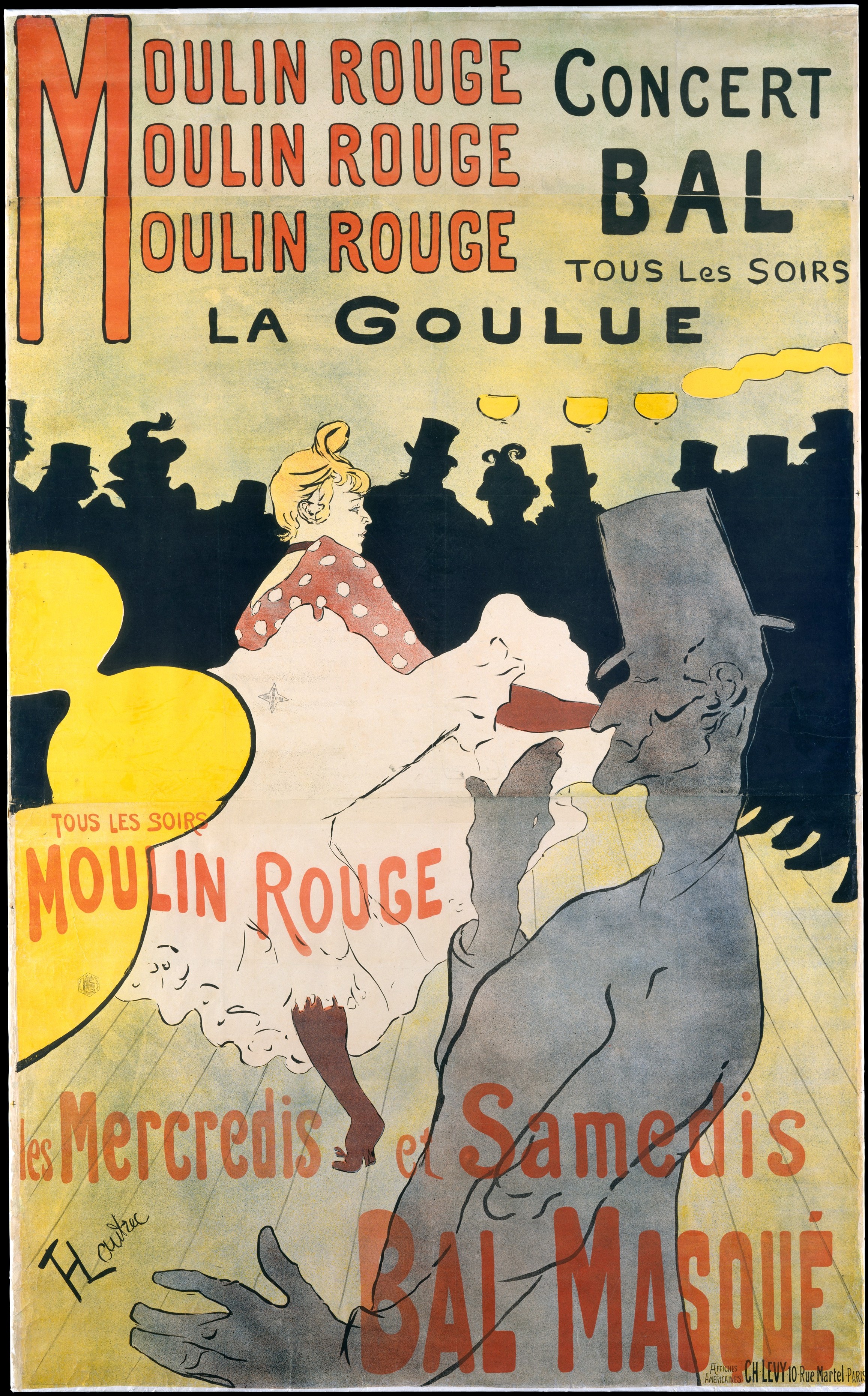

However, it is in the prints that Toulouse-Lautrec created as advertisements for the Moulin Rouge (and other, less famous, establishments) that the Japanese influence really shines through. The figures are bold, and outlined in smooth black lines, there is not a hint of traditional light and shade: the prints look markedly different to Toulouse-Lautrec's western predecessors, and markedly similar to Japanese woodblock prints. Toulouse-Lautrec had taken the Japanese woodblock and repurposed it completely for his own ends.

Moulin Rouge: La Goulue

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901)

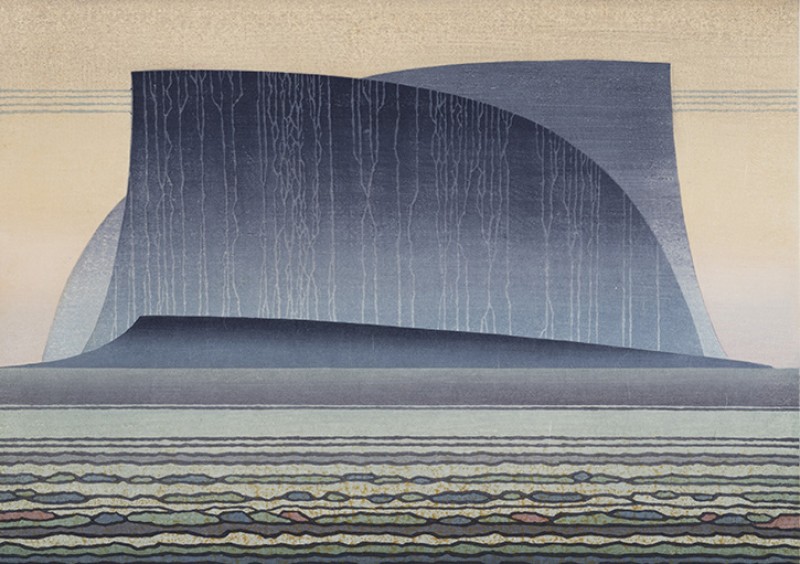

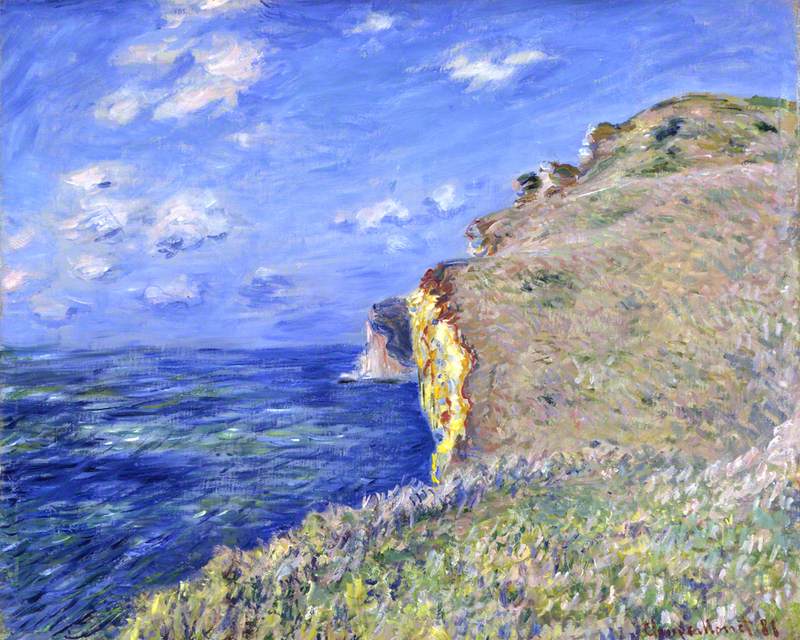

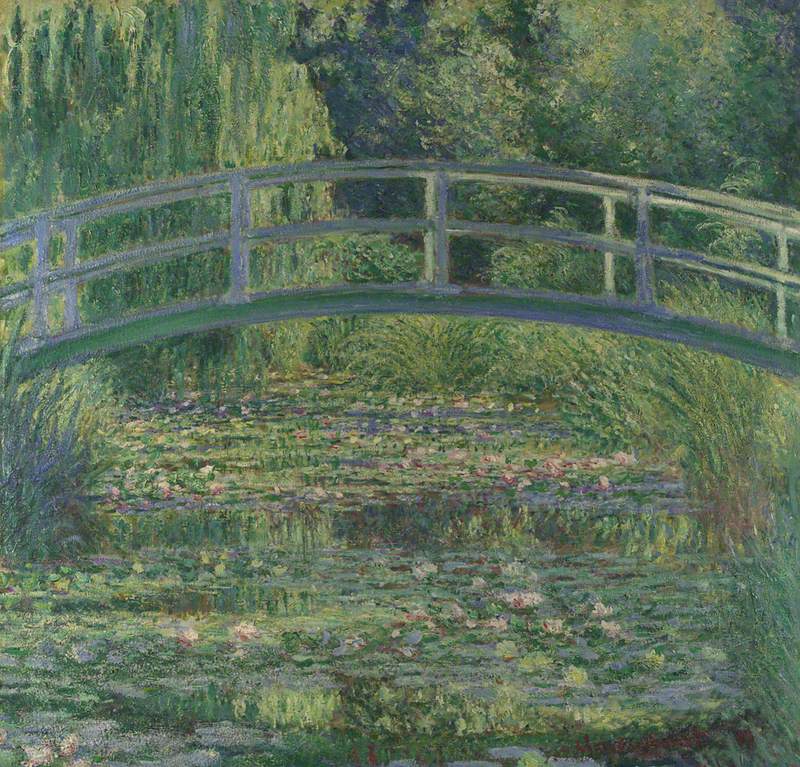

It's worth noting that Japonisme, while at its peak in France, was not unique to the Impressionists. Artists across the West felt the influence of art from Japan, and the Japanese aesthetic and way of thinking crept into the work of artists in London and New York. It also went beyond painting, with the creation of imitation gardens, textiles and furniture: Monet modelled parts of his Giverny garden, including the famous bridge over the lily pond, on Japanese gardens.

The impact on the French artists was the greatest because of the timing: the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists were looking for something different, and found it in ukiyo-e prints. The decorative depiction of the 'floating world' united artists thousands of miles apart, from very different cultures.

As Toulouse-Lautrec said, 'I have tried to do what is true and not ideal.'

Molly Tresadern, Art UK Content Creator and Marketer