The main festival of Christianity is Easter, a celebration representing Christ's Resurrection after the Crucifixion. But what happened after that? And how have the following Biblical events been captured by artists throughout the centuries?

In the Bible, the four Gospels differ in their accounts, but the general consensus is that Jesus told his disciples to spread the word.

In Luke's Gospel alone, Jesus himself then ascends to heaven. The same author of the Gospel of Luke is thought to have written the Acts of the Apostles too, and this ascension is mentioned in the first chapter of that book, taking place forty days after the Resurrection.

The Gospel of Mark mentions an Ascension, but scholars largely agree that it's a later addition.

Today the Church celebrates the Feast of Ascension 40 days after Easter Sunday, on a Thursday, in accordance with the Book of Acts. Unlike Christmas or some other Christian feast days, the date is moveable, as Easter itself is.

The feast has been celebrated for many centuries, and it is one of only a handful of ecumenical feasts, meaning that for most of ecclesiastical history all Churches – Orthodox, Catholic, Protestant – observed it. (While the Anglican Communion continues to celebrate it, other Protestant denominations have abandoned the practice.) As such, over time, the moment has been represented in art in different ways.

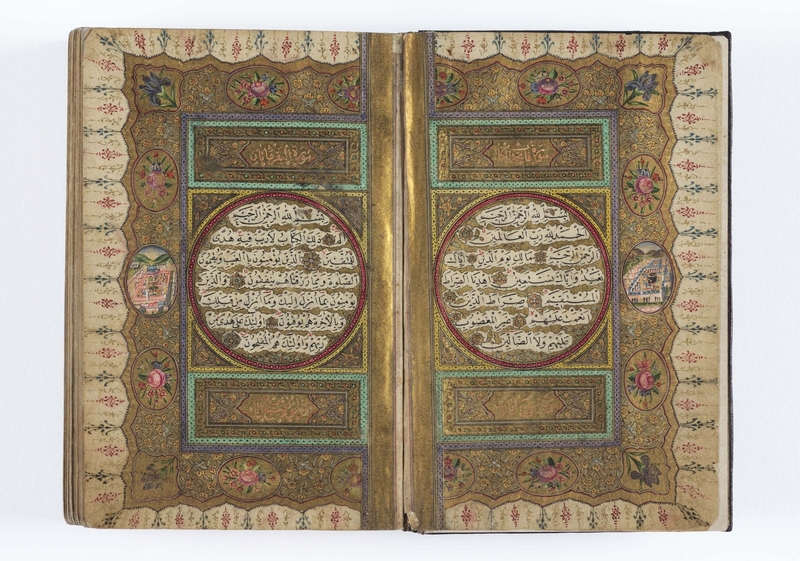

One of the earliest surviving representations is in the sixth-century Syriac Rabbula Gospels (Rabbula is the name of the scribe). This remarkable survival is now in the Laurentian Library in Florence.

View this post on Instagram

Another early type of depiction of the Ascension saw Jesus climbing up to heaven, helped by the hand of God.

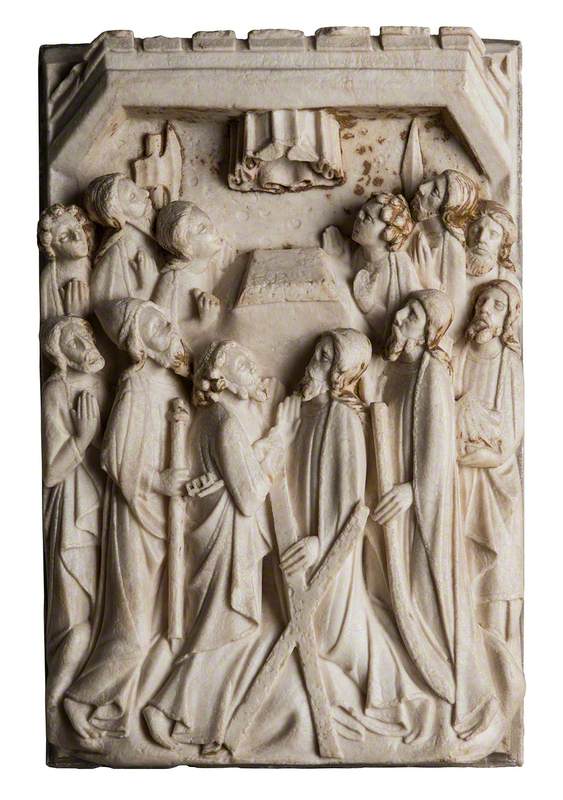

This ivory relief (the so-called 'Reidersche-Tafel') was carved around AD 400 in Milan or Rome. It is now in the Bavarian State Museum in Munich.

View this post on Instagram

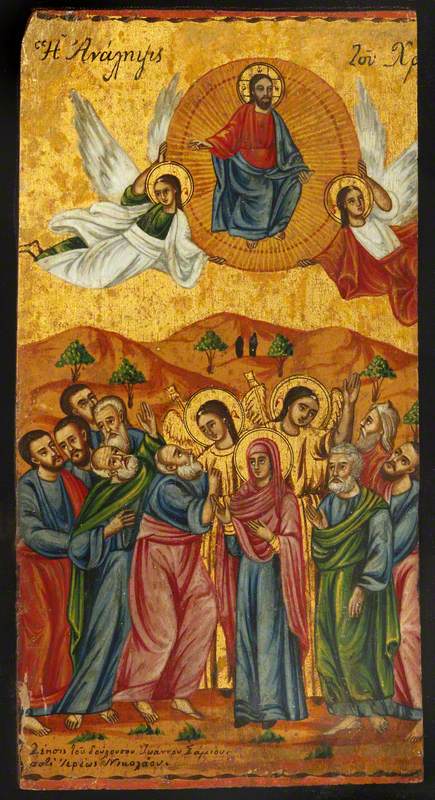

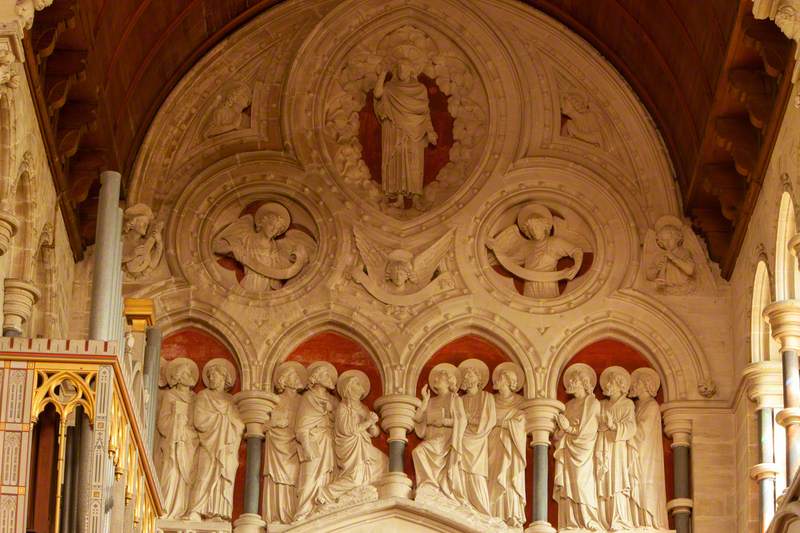

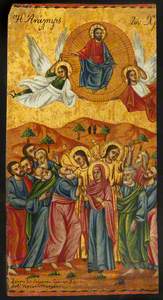

In the medieval period, from the ninth century onwards, the Ascension was portrayed on domes within churches – the literal link of Jesus ascending to heaven represented in a place where the viewer is looking up to the sky. Jesus would often be flanked by angels on his ascent. This idea would continue into the Renaissance and beyond.

The Ascension

(copy after Leandro Bassano) c.1651–1656

David Teniers II (1610–1690)

The later medieval and early Renaissance periods in western art saw the Ascension depicted in a standardised form, with the figure of Jesus up in the air, sometimes framed in a mandorla, and the disciples and the Virgin Mary on the ground, looking up.

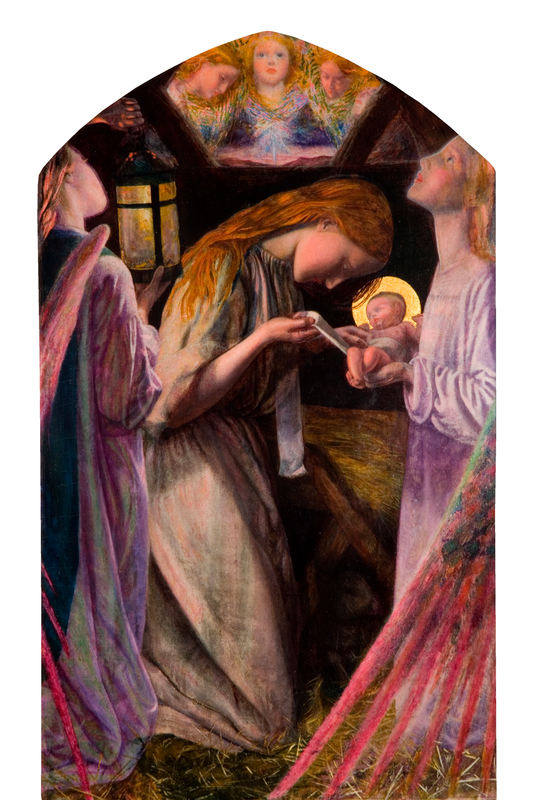

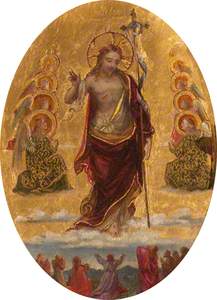

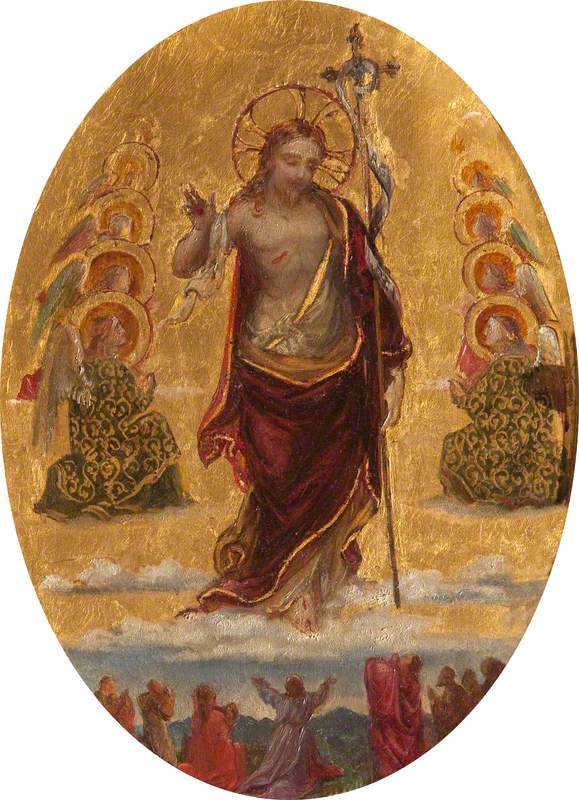

The Risen Christ (The Ascension)

c.1877

Rebecca Dulcibella Orpen (1830–1923)

Often Jesus would be making a sign of benediction with his right hand, to signify the Church was blessed.

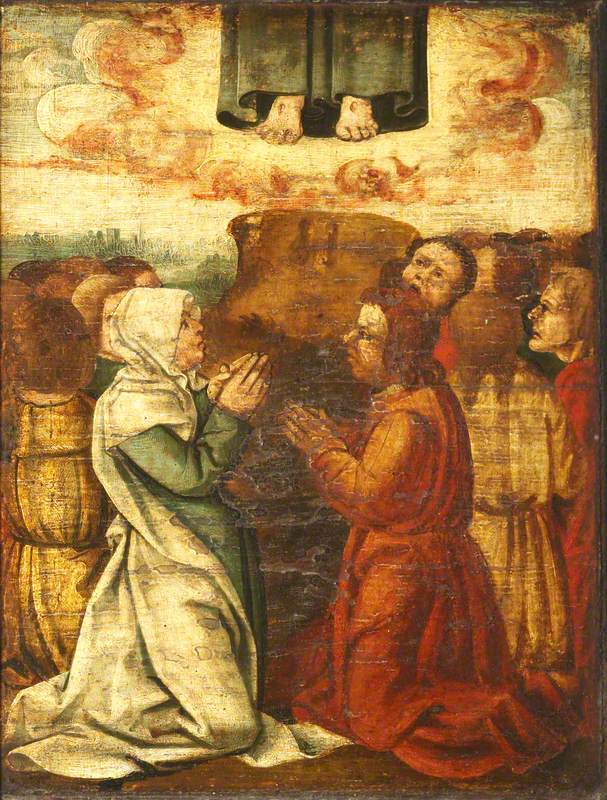

One of the variations in Romanesque and Anglo-Saxon depictions of the Ascension showed the bottom half of the overall scene, with the earthbound figures on the ground but with Jesus' feet disappearing at the top of the image.

This rendering became popular across northern Europe, and remained so longer than elsewhere. Albrecht Dürer was to use this version in his Small Passion series of 37 woodcuts.

The Ascension of Christ

c.1510, woodcut by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

Although both the 'disappearing feet' and 'hand of God' motifs seem perhaps comical to modern eyes, these artworks expressed a deep devotion. The artists were trying literally to depict a moment of miraculous religiosity – one that was only vaguely described in the written sources, and left a lot to the artist's own imagination.

As the centuries rolled on, and the Renaissance arrived, artists such as Giotto, Mantegna and Dosso Dossi completed Ascension works, usually made to be viewed in situ inside churches – a British example from the late 1600s is this ceiling from Trinity College, Oxford.

This tradition continued with the likes of Rembrandt, Rubens and Hogarth. The Hogarth in particular is of interest as it is his largest known work. Today you can see it inside St Nicholas Church in Bristol. It was originally painted for St Mary Redcliffe in 1755/1756, and the Ascension scene is just the central canvas of a vast triptych.

The Altarpiece of St Mary Redcliffe: The Ascension

(triptych, centre panel) 1755–1756

William Hogarth (1697–1764)

The painting was Hogarth's only commission from the Church of England, for which he was paid £525. Unfortunately, Hogarth's work fell out of fashion during the Victorian era and the church tried to sell it off. However, in 1859 it was given to the Bristol Fine Art Academy (later the Royal West of England Academy) but its size made it difficult to display – so it was rolled up and stored in the basement.

Fortunately, the tale has a happy ending, as Bristol Museum & Art Gallery officially acquired the triptych in 1955. It has been on display at St Nicholas Church since the 1970s.

As with many fashions in art, royalty saw the popularity of this kind of work to decorate their residences. In the late eighteenth century, American-born artist Benjamin West had moved to London and established himself as one of the leading artists of the day. He was commissioned by George III to decorate the walls of the Royal Chapel at Windsor Castle with Bible scenes, which took him twenty years.

This Ascension sketch in the Tate collection was painted in about 1782 and shows the influence of Raphael. But it was never installed in the chapel, as George appointed a new architect and the commission was cancelled. Twenty years later, West returned to the subject and produced another version which is now in the collection of Denver Art Museum.

John Constable isn't the first name you might associate with religious paintings – he's best known for his landscapes of the English countryside. He did, however, paint a version of the Ascension for a church in his native Stour Valley in Suffolk.

It is one of only three religious paintings by Constable, and was commissioned as an altarpiece for St Michael's Church, Manningtree, in 1821 – the same year he completed perhaps his most famous work, The Hay Wain.

The figure of Christ floating in the sky surrounded by clouds dates from the same period as Constable's sky studies in which he was developing his own religious and landscape ideas. It was installed in 1822 in the newly built chancel of St Michael's until the church was demolished in 1965.

The painting was acquired by All Saints, Feering, where it stayed until it became too expensive to keep properly. After efforts to allow a museum to acquire it, the Constable Trust was formed in order to buy it and return it to the area for which it was painted. It is now on permanent display in Dedham church.

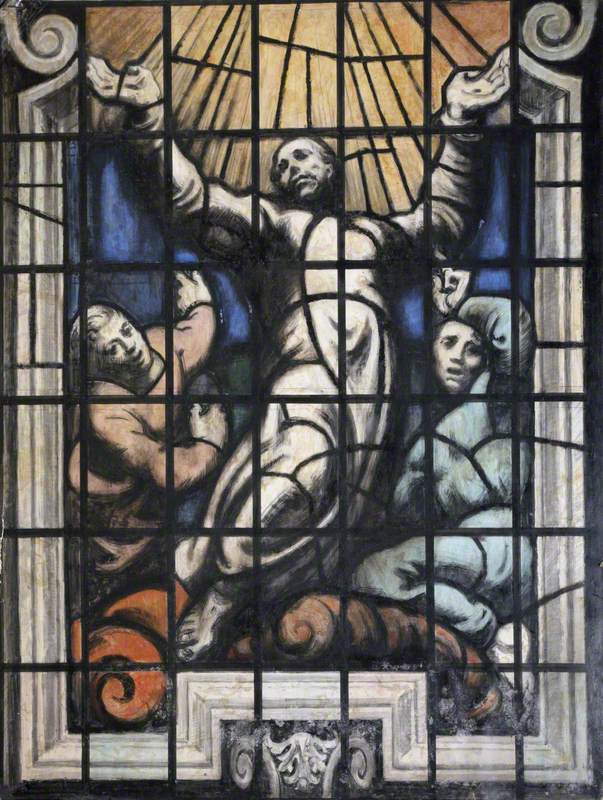

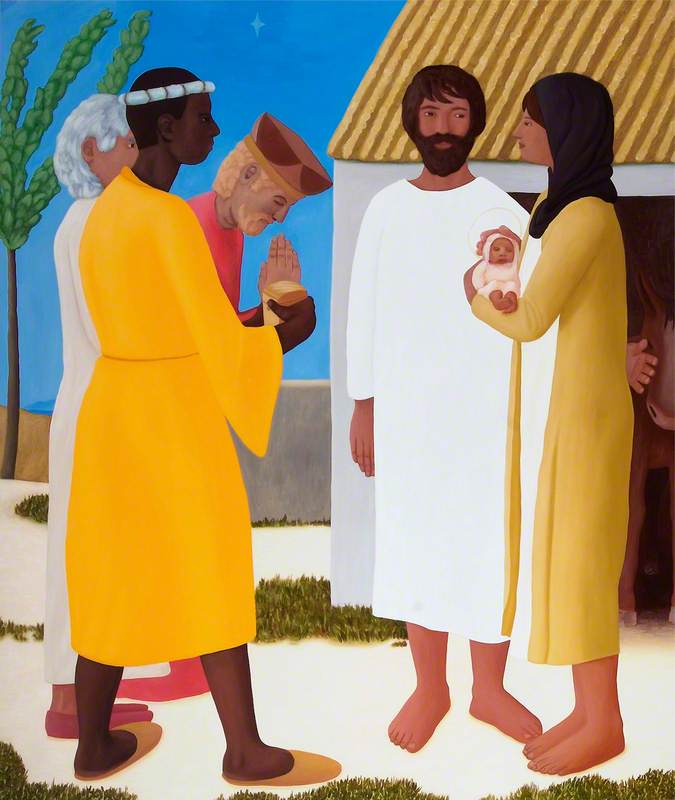

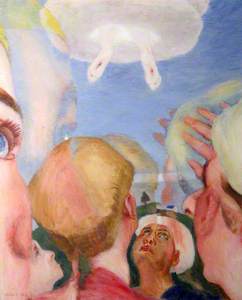

More modern interpretations of the Ascension story may seem to have broken away from tradition, but most owe some debt to the art of the past.

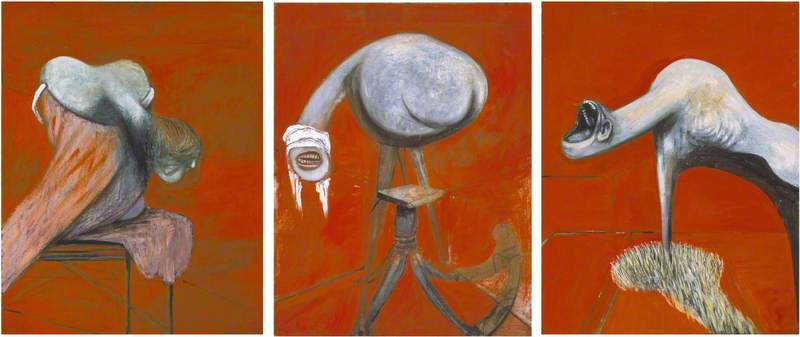

The Ascension

(triptych, centre panel) 1962

Francis Ferdinand Maurice Cook (1907–1978)

This work by Sir Francis Cook is typically vivid, with the use of bright colour and plenty of detail. But although the figures and setting are decidedly modern, it retains echoes of the works of the preceding centuries, with its composition largely unchanged from the Renaissance ideal.

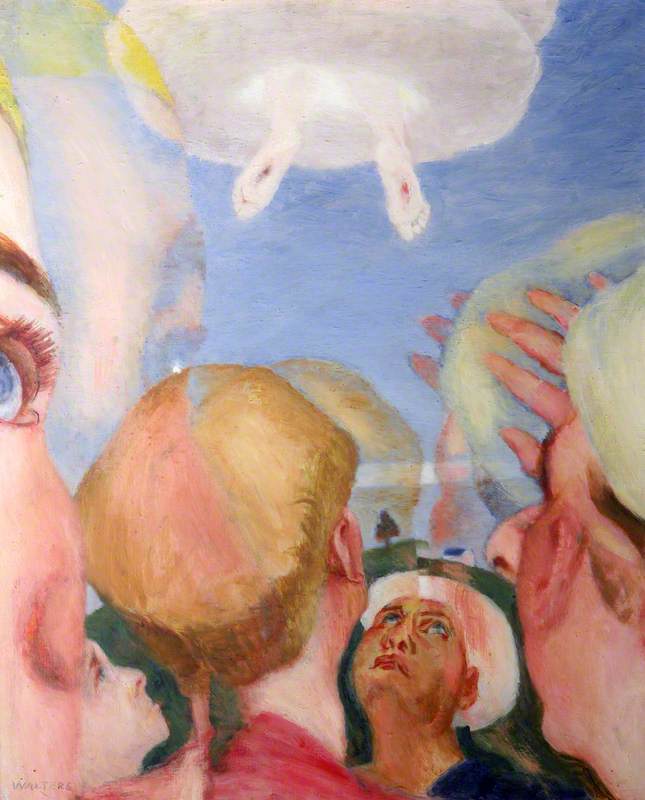

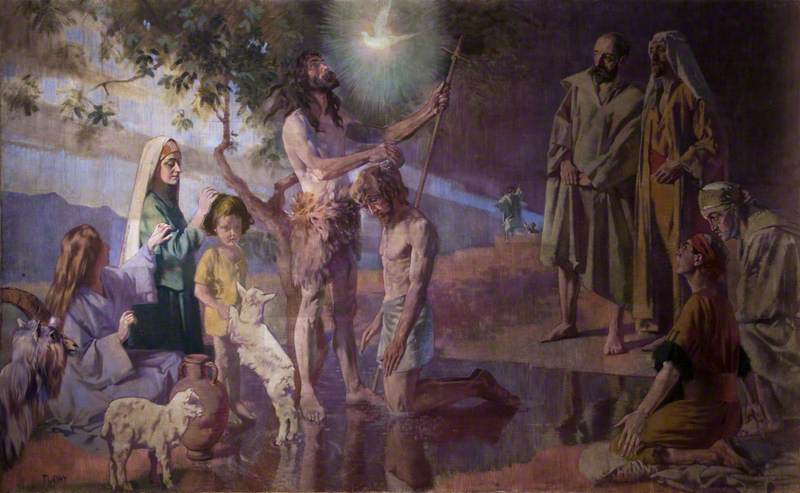

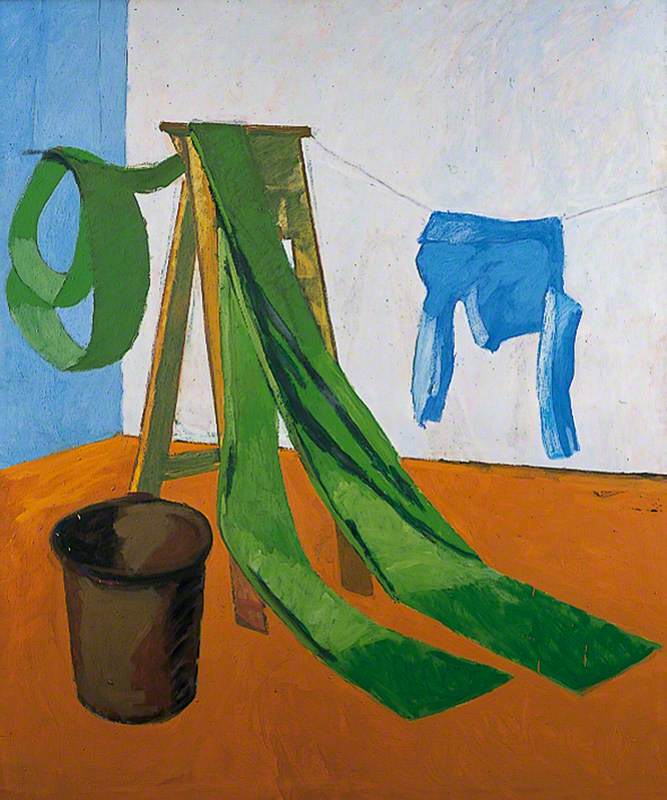

Other artists have 'put the camera' elsewhere, such as in this work by Welsh painter Evan Walters.

The confusion of the disciples is made more pressing by having the viewpoint within the assembled crowd. At heart though, it too recalls the works of the past, with it being a variation on the 'disappearing feet' style of Ascension.

Karin Jonzen's work in the chapel of Selwyn College, Cambridge is a simplified version of the overall scene, with just the heavenly aspect visible – Jesus flanked by angels. The black figures on the light background of the wall seem almost minimalist, although the central idea of Christ and angels goes all the way back to the Rabbula Gospels.

Today, straightforward religious art is not fashionable, and religious subjects are generally not undertaken by the big names of the art world, unless with a sense of irony or subversion.

However, works depicting religious subjects formed such an integral part of western art through its history, and trying to understand them can perhaps help us understand our history more generally.

Andrew Shore, Head of Content at Art UK