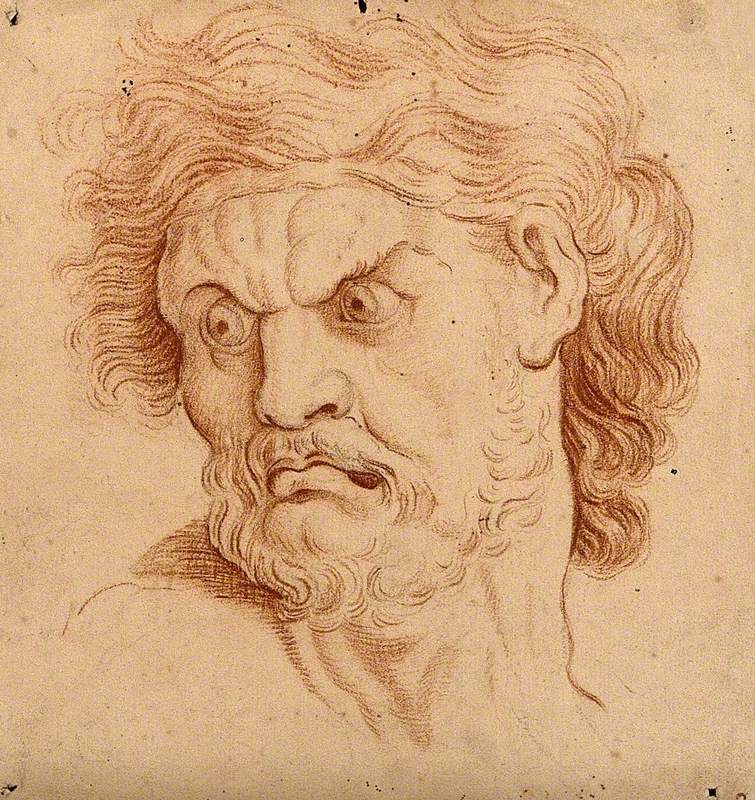

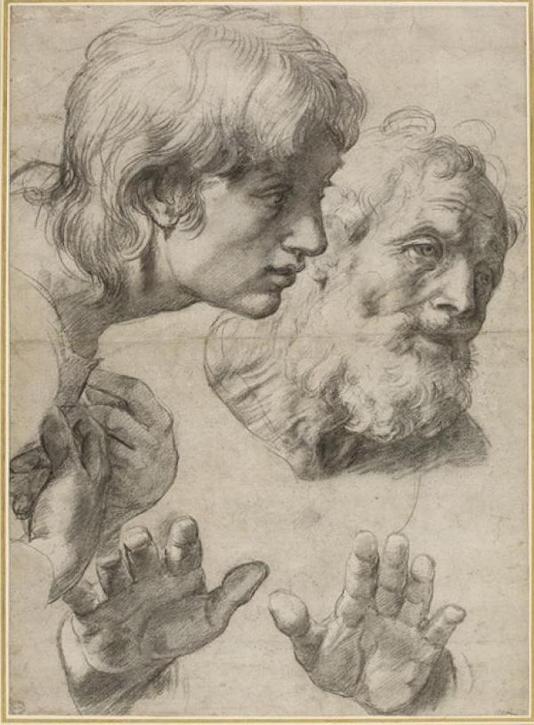

Trying to define drawing is like walking in the foothills of a mountainous region and attempting to establish the exact point at which one range meets another. The high peaks are easy. See that one rising in the centre of 'Drawings'? Oh yes: that must be Leonardo da Vinci. Towering near it are Michelangelo and Raphael, Holbein and Ingres. All indisputable draughtsmen who took sheets of paper and chalk, ink, metalpoint or graphite and observed, experimented and planned, creating some of the world's most charismatic and beautiful drawings.

Studies of Two Apostles

c.1519–1520, black chalk with faint white chalk highlights by Raphael (1483–1520)

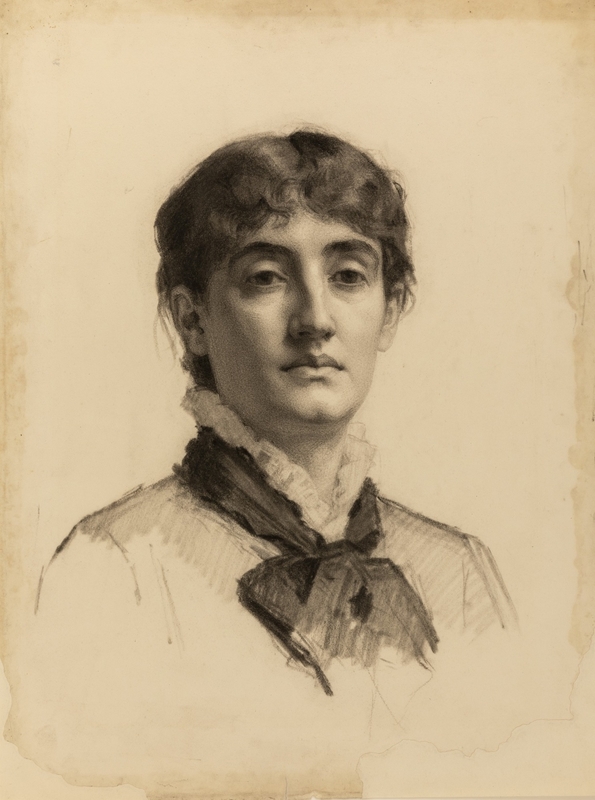

Elsewhere, towards the edge of the range, categories can be harder to judge. That one is Rosalba Carriera. In her studio in Venice, Carriera used pastel on paper, which needed no drying time like oil paint. It made financial sense: her subjects – often young men on the Grand Tour – could have their portraits collected as soon as they were complete and packed to be shipped back home. It made artistic sense, too: the soft, powdery surface of pastel could convey the sensuous lustre of skin, hair and eyes and hint at subtle psychological states. Her chosen medium persuades us to corral her portraits with drawings, but the results are so dense, so painterly, that one could argue for the territorial line to be drawn on its other side and include it in the neighbouring range of 'Paintings'.

Gustavus Hamilton (1710–1746), 2nd Viscount Boyne

1730–1731

Rosalba Giovanna Carriera (1673–1757)

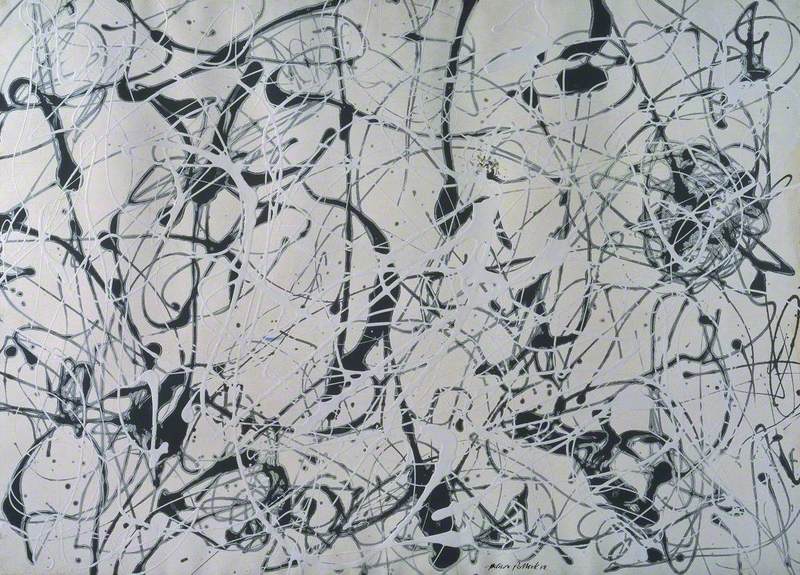

The rugged crag closer at hand is Jackson Pollock. The directness and spontaneity of his lines suggest drawing, but through repetition and layering, and his use of thick, viscous materials such as enamel and gesso, his pictures acquired the substance of paintings. Where do we draw the line? Lee Krasner described his works as 'monumental drawing, or maybe painting with the immediacy of drawing – some new category'.

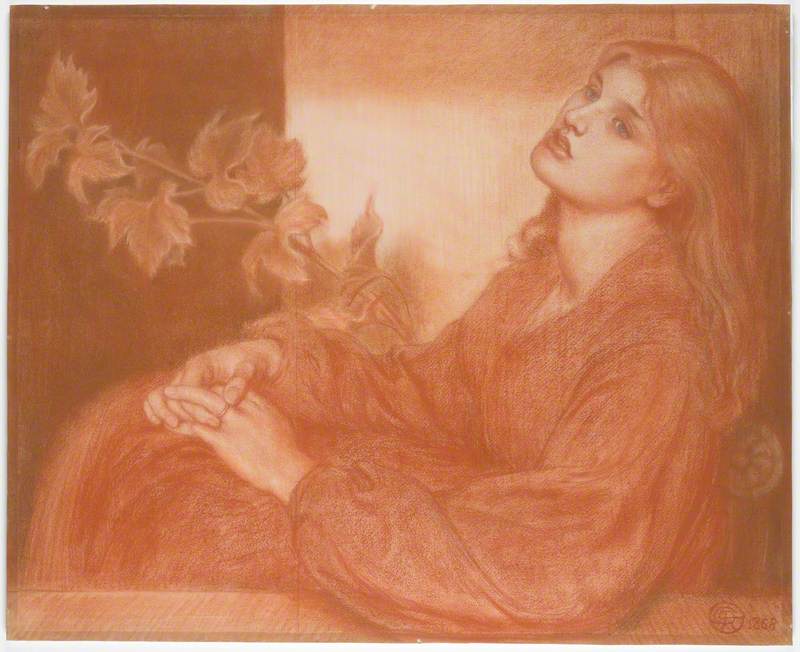

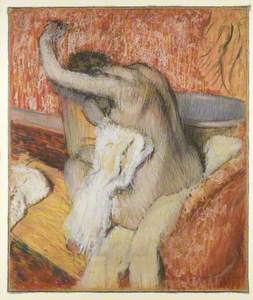

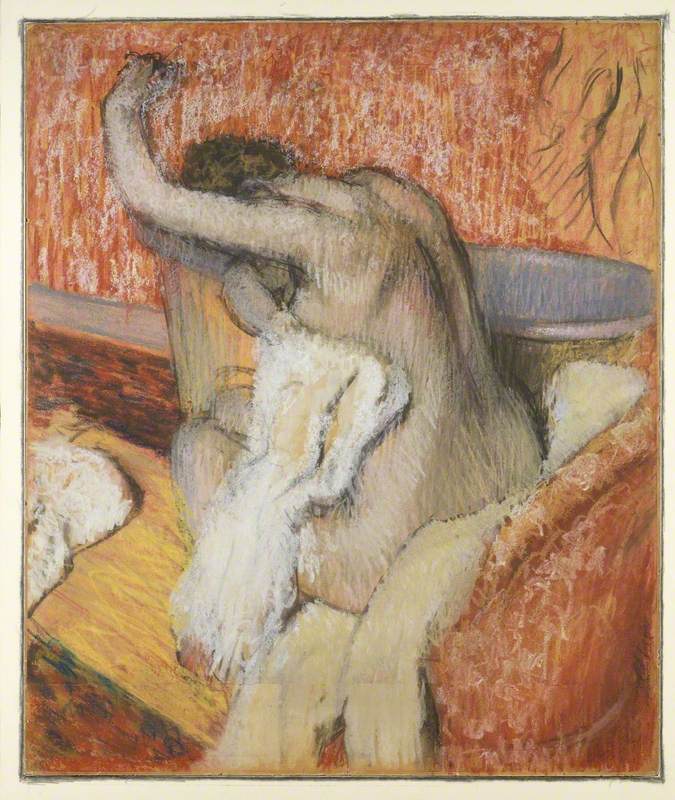

Whenever a certain density of pigment is reached – whether as the result of a medieval illuminator adding touches of bodycolour to the inked outlines of an initial letter, or Edgar Degas dragging dazzling pastel colours across the paper, layering and experimenting with wet and dry pigments – we find ourselves in debatable land.

After the Bath – Woman Drying Herself

c.1895

Edgar Degas (1834–1917)

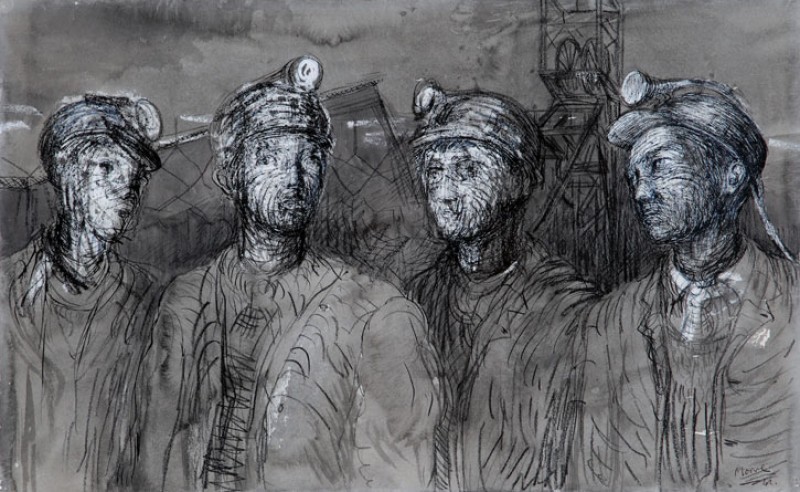

Definition began to be an issue in the second half of the nineteenth century, when Impressionist artists such as Degas and Berthe Morisot stopped regarding drawing as a means of planning sculptures or oil paintings and seized on media such as pencils, watercolours and pastels because they allowed them to capture events in the fleeting and fragmented ways in which they actually unfolded. It was only through drawing that their hands could keep pace with the kaleidoscopic, fast-moving visual world. This group of lateral thinkers began to use drawing media to make independent works of art – Krasner's 'new category' wasn't so new after all. Though the question of which of these disparate works can be called 'drawings' remains moot: when in 2023 the Royal Academy held an exhibition of Impressionist drawings, the organisers were careful to call them 'works on paper'.

Berthe Morisot Drawing, with Her Daughter (Berthe Morisot dessinant, avec sa fille)

1889

Berthe Morisot (1841–1895)

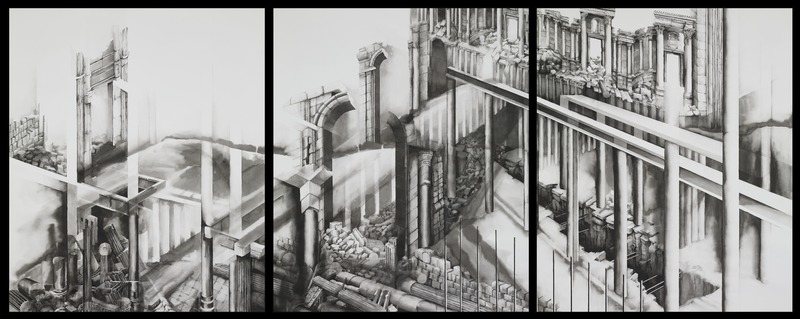

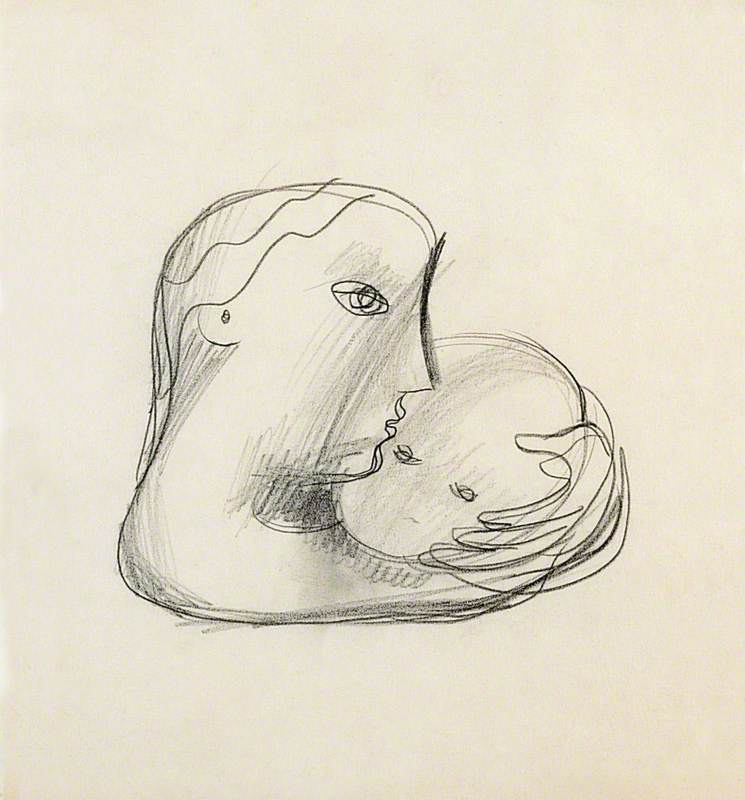

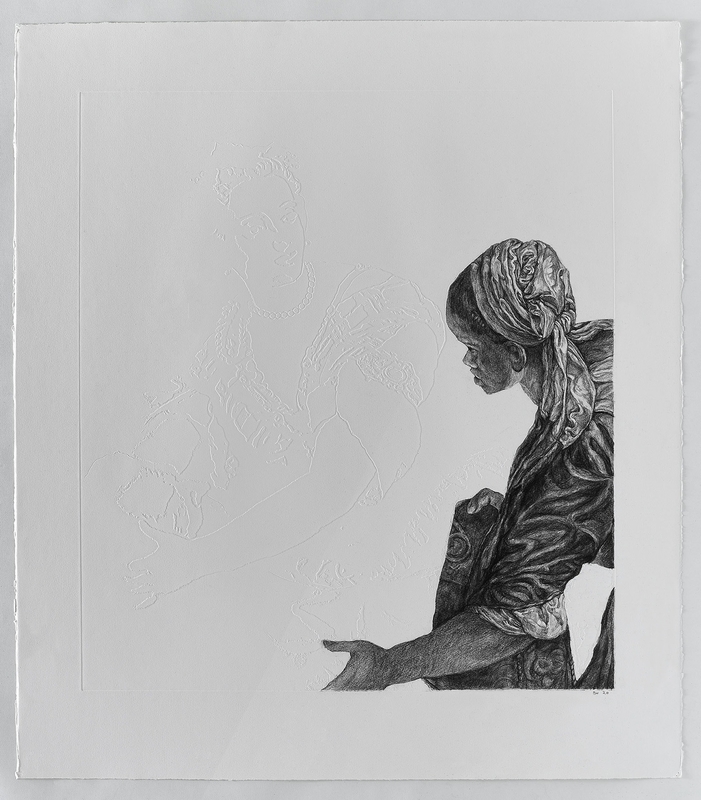

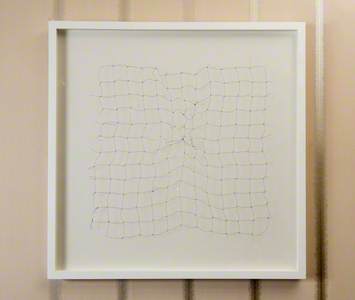

Another great period of change came in the 1960s and 1970s, when categories of art practice were radically rethought. New ones like video and conceptual art were introduced and boundaries between movements dissolved. Drawing, operating as a fully independent medium, became a way to explore some of the most fundamental questions: how to express one's sense of self, one's place in the world? Subtle truths about the human condition?

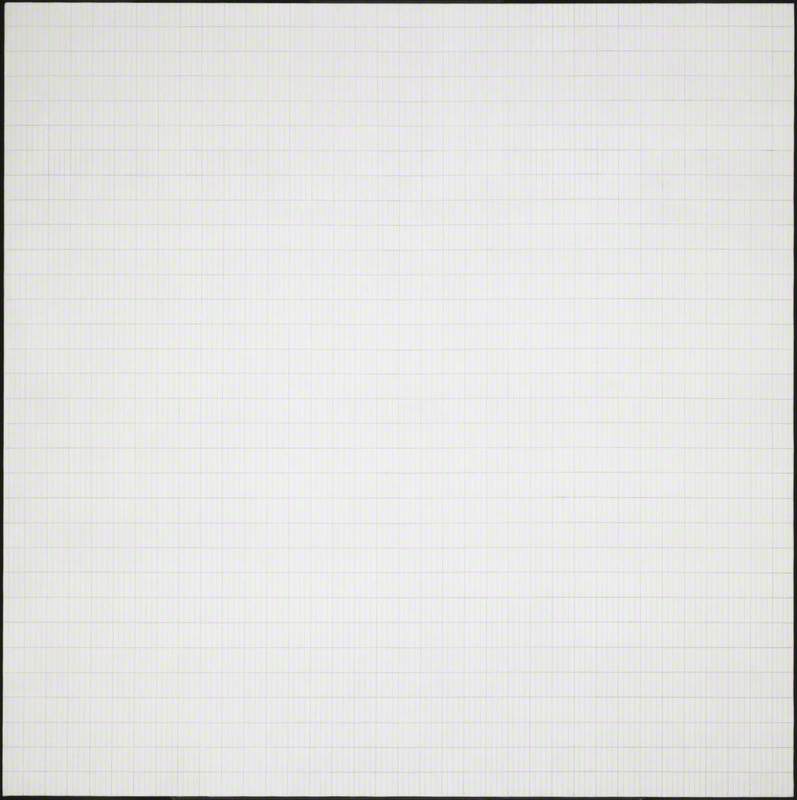

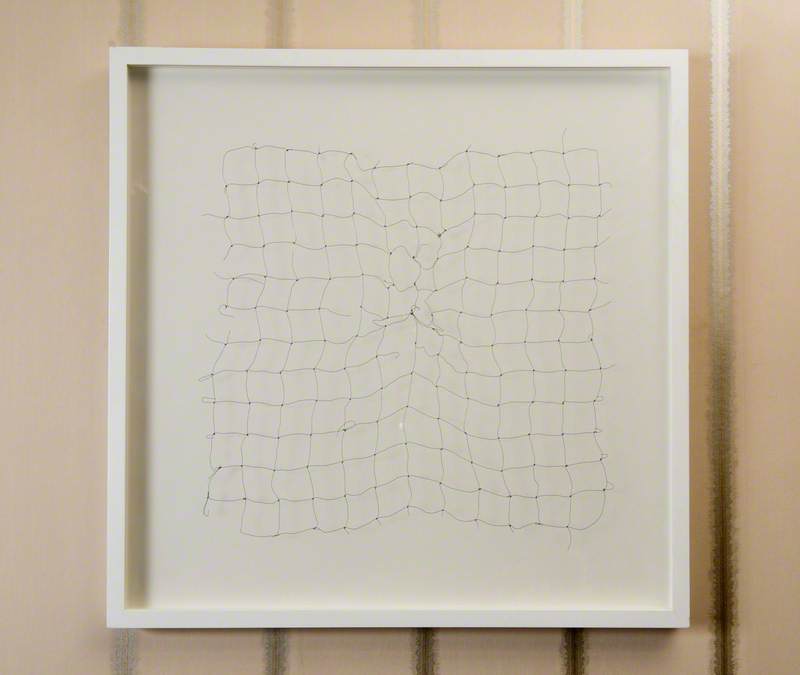

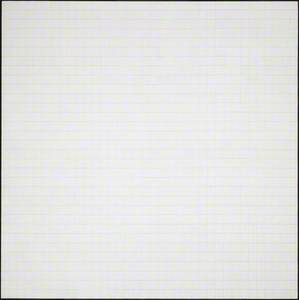

Around 1960, when living in a block of artists' lofts in lower Manhattan, Agnes Martin devised a hybrid work of art that took elements from both painting and drawing: she began by staining the canvas with a wash, then covered it with an even grid of delicate, ruled pencil lines. The network of a work like Morning (1965) imposes order on its environment like a clock ticking as it marks the slow passage of time. This large-scale drawing unfolds its meanings over time, slowly drawing its viewers into its emotional force field.

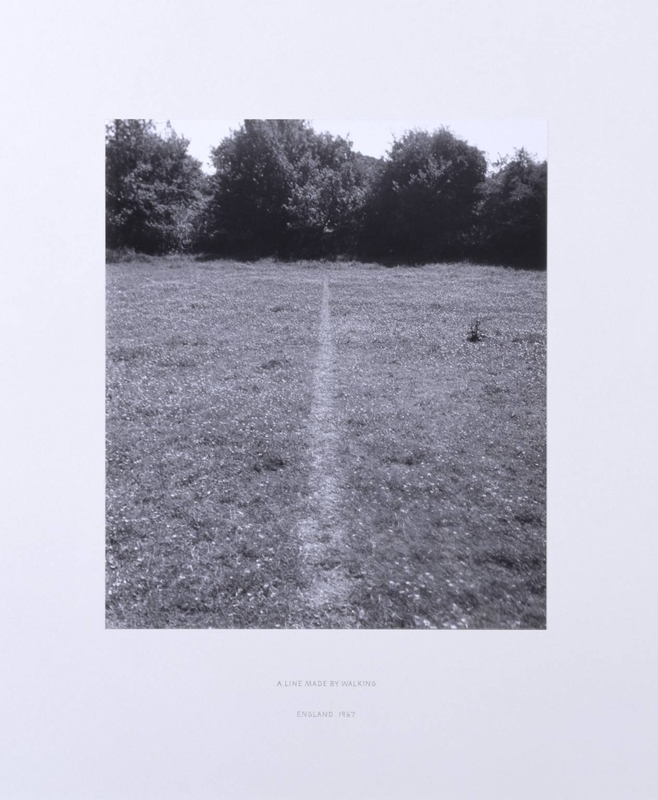

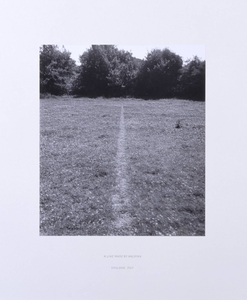

Land art comes into the story too. Was Richard Long making a drawing when in 1967 he walked up and down a field to create A Line Made by Walking? Never mind taking a line for a walk – he was taking a walk for a line. And if we allow Long his turf-drawing, what about the late Bronze Age people who cut into the chalk downland near what is now Uffington in Oxfordshire to create a gigantic linear image of a horse? Or the Nazca people who made vast geoglyphs of hummingbirds and spiders in the Peruvian desert? And since we are on the subject of prehistory, it seems a good moment to point out that it would be more accurate to describe most cave 'paintings' – outlines of humans and animals inscribed onto the rock with charcoal and earth pigments – as cave drawings.

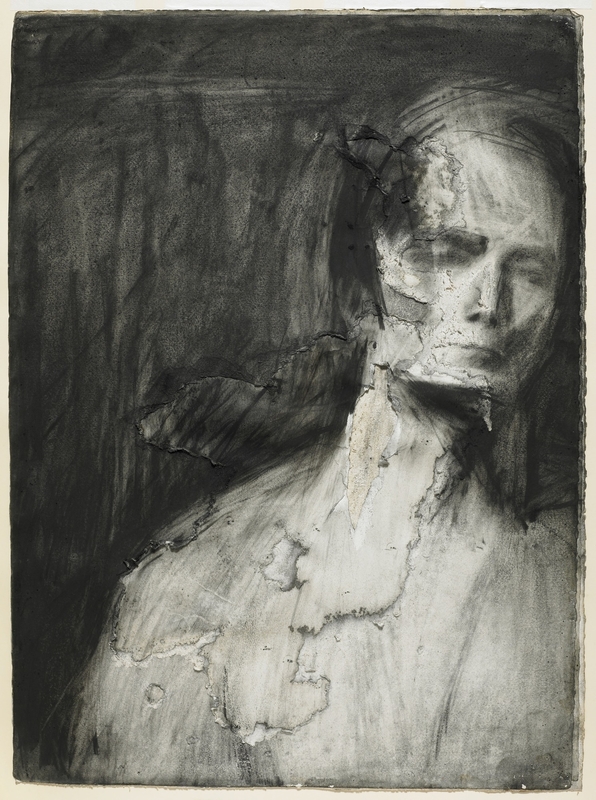

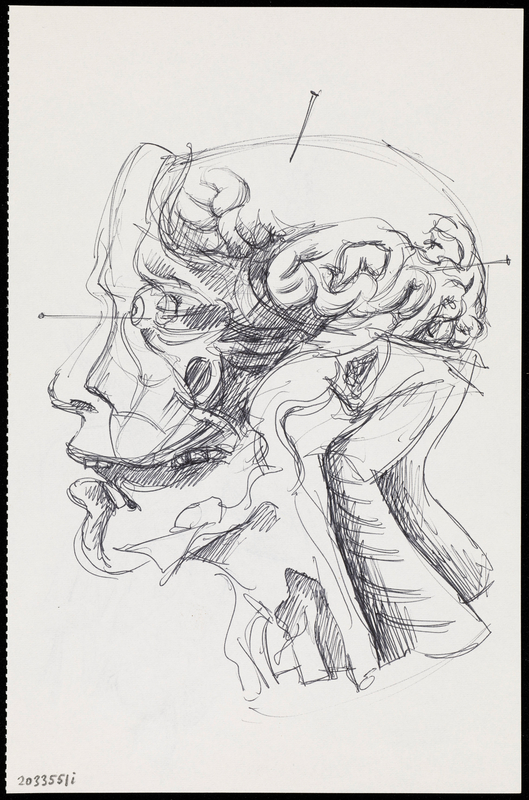

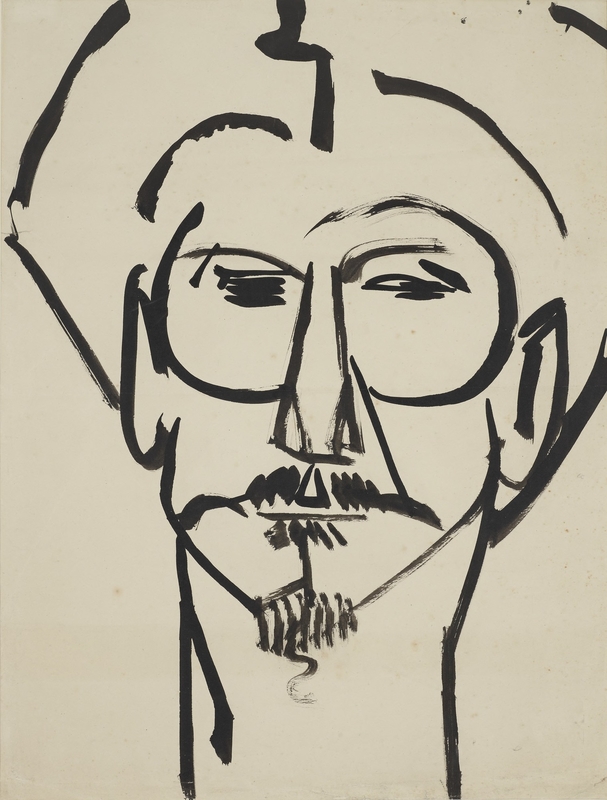

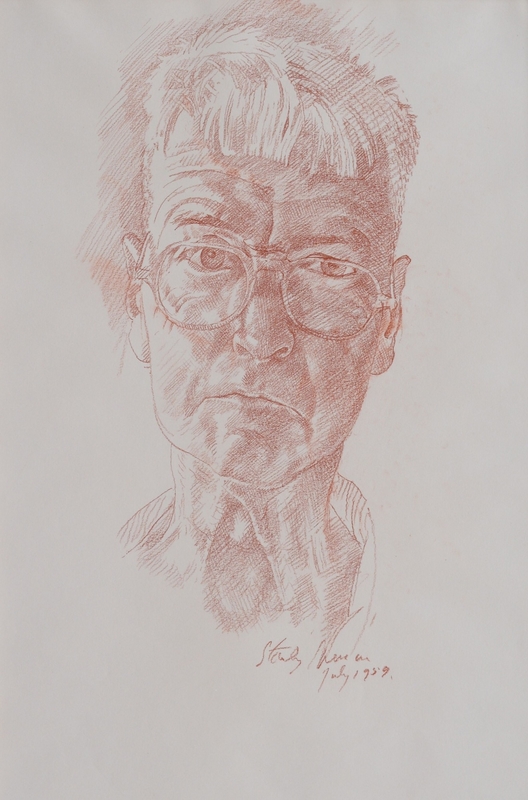

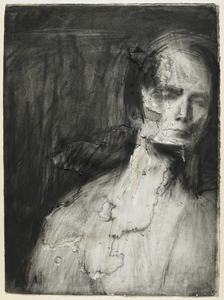

But is it a question only of medium or density – could drawing also be described as a state of mind? William Blake once wrote: 'Let a Man who has made a Drawing go on & on and he will produce a Picture or Painting but if he chooses to leave off before he has spoild it he will Do a Better Thing.' What Blake means, I think, is that the best drawings are speculative, sketchy and full of potential. They are imagination in action, before it gets weighed down and compromised. They are part of a process. Think, for instance, of how Frank Auerbach creates portraits by drawing and erasing, drawing and erasing until the paper is scuffed and abraded: searching with charcoal and eraser until he feels he has expressed something of the presence of that person sitting in his studio.

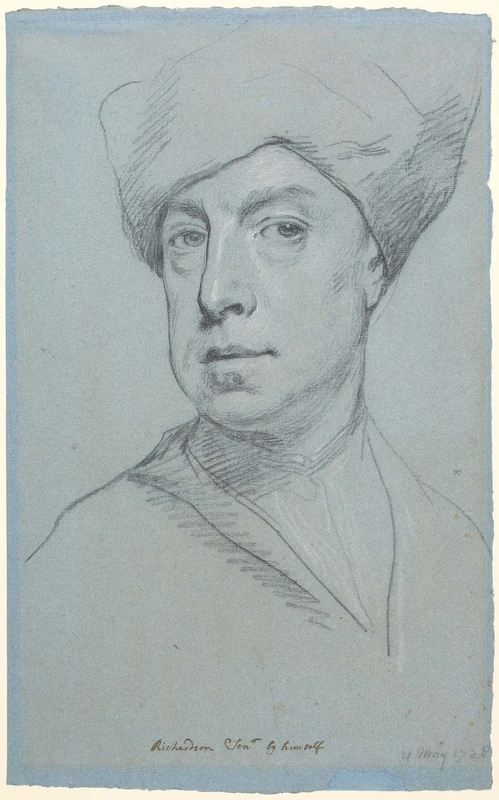

In his use of drawing to discover profound truths of identity and selfhood, Auerbach is successor to the eighteenth-century portraitist Jonathan Richardson. Richardson thought that a painted portrait should be grand and dignified, but his focus on the outer person at the expense of the inner self eventually came to nag at him. Later in life, he made hundreds of self-portrait drawings in a sustained attempt to explore private aspects of his own character and his changing moods. In some of these drawings, he is playful and strikes a pose; in others, he is quizzical and vulnerable. The privacy and licence of drawing allowed him to confront his own ageing features with unflinching honesty, and explore corners of the self he could never reach with his paintbrush.

Perhaps it is in the nature of drawing to be marginal: an arena for experimentation and questioning. This licence is apparent in the expansion of materials artists draw with. The days when you could specify charcoal, chalk, graphite, ink, pastel, crayon and watercolour are long gone. Any attempt to devise a definitive list of rules and regulations would be quixotic. What constitutes a drawing is being reimagined right now in ways that are playful, inventive, experimental and provocative.

Today, artists draw with fire, wire, pinpricks and neon. Rebecca Salter draws by burning thin Japanese paper with a heated tool, creating tiny repetitive marks that build up into subtly undulating shoals; Cornelia Parker with rattlesnake venom and bullets melted down and extruded. Emma McNally creates immersive environments with room-sized, drawing-crammed chalkboards and hybrid drawing-sculptures. The mountain range is expanding, its borders becoming ever more blurred. These are exciting times for drawing – however, you choose to define it.

Susan Owens, writer and art historian

Susan's latest book is The Story of Drawing: An Alternative History of Art, published by Yale University Press

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation

Further reading

Bernard Harper Friedman, Jackson Pollock: Energy Made Visible, Da Capo Press, 1972