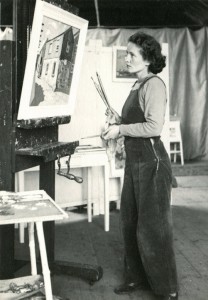

'Rules to Keep the World Away' are the words that Welsh artist Gwen John (1876–1939) began her notebook with, in 1912.

There were ten rules. On her list were: 'Do not listen to people (more than is necessary)', 'Do not look at people (ditto)', 'have as little intercourse with people as possible'... 'when you have to come into contact with people, talk as little as possible'… 'do not look in shop windows.'

Against the backdrop of today's social distancing, John's diary excerpts feel a little too close to home. All that is missing is the designated 'two-metre distance'.

Around 94 years after John wrote in her diary, author Margaret Forster borrowed the artist's words for the title of Keeping the World Away, a book that opens with a semi-fictional take on John's struggles as an artist, and her fraught relationship with sculptor, Auguste Rodin.

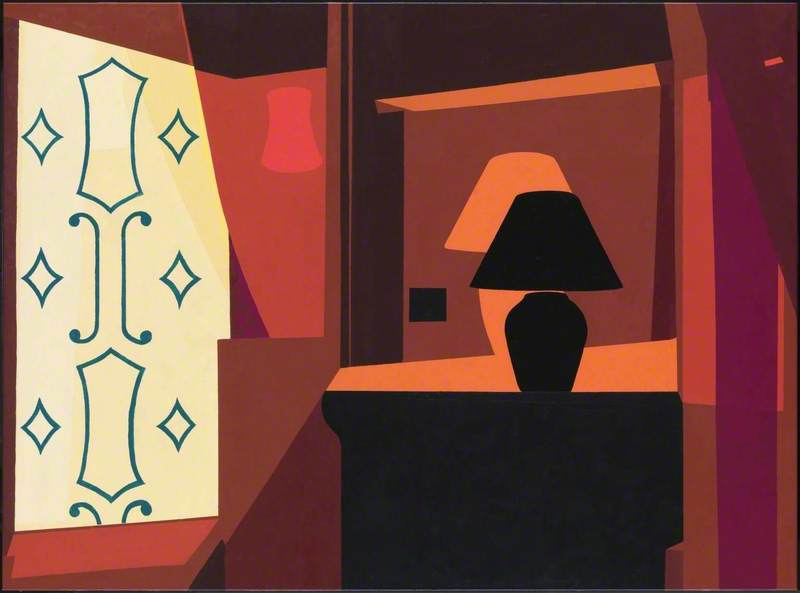

The book carried a cropped image of her painting A Corner of the Artist's Room in Paris on its cover. John loved the corners of empty rooms. Her ghostly interiors are frequently paired with Virginia Woolf quotes (but I'll spare you yet another comparison here).

Since John's death in 1939, there has been a fascination with her perceived 'reclusiveness' that has reached the point of mythology.

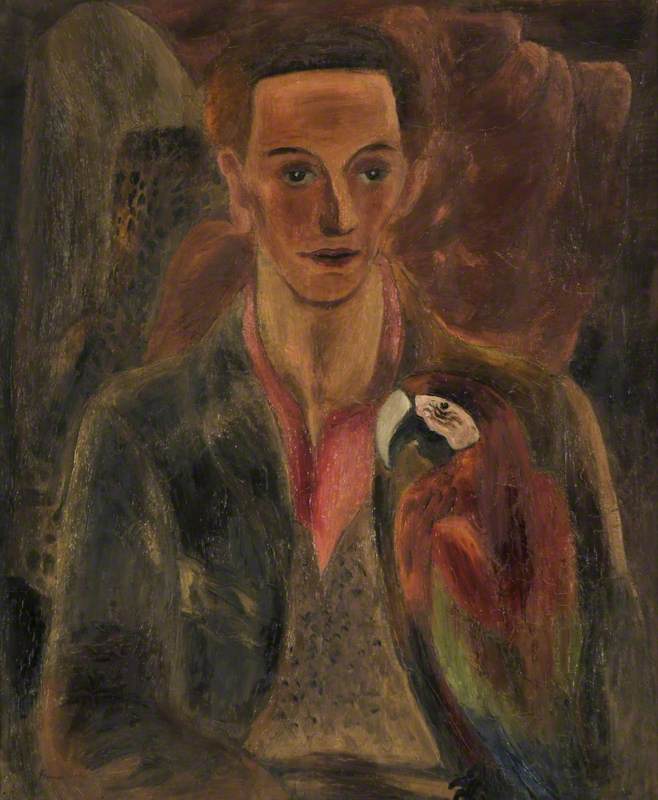

The story, as it's usually told, is of an artist eclipsed in her lifetime by her more famous and gregarious brother, Augustus Edwin John. She is often remembered first and foremost as an artist who fell in love with Rodin while working as his model to support her own painting. She later becomes obsessed with him, and a long, complicated affair followed. Eventually, she was rejected by Rodin and turned to Catholicism, spending the rest of her life in seclusion, painting the nuns and small children that attended the convent near her home in Meudon, in the suburbs of Paris.

It's sometimes suggested she replaced her need for Rodin with God, as though the flaming myth of untouchable genius needed any more fuel. Even her death was fairly mysterious – after getting an urge to visit the sea, she travelled to Dieppe without any luggage, and collapsed in the street.

John's position as an outlier who did not follow a line of influence or formal art movement has fed into the marginalisation of the 'woman artist' from that period – where she is treated as the exception to a rule.

It's true that many of her female peers at the Slade School of Fine Art saw their artistic careers stalled by marriage. Edna Waugh struggled to produce work and meet the demands of domesticity her husband placed on her. Ida Nettleship (John's sister-in-law) gave up painting completely.

For John, solitude may have been a form of self-preservation, a chance to keep the trappings of traditionalism on the outside. But she never retired from life. She remained in touch with many of her family members and friends until it came to an end; she was a part of a religious community in Meudon.

Her 'nun paintings' from that period are among her most impressive works. Her portrait of Mère Marie Poussepin – the founder of the local convent which John painted from a prayer card – is an almost supernatural oddity. It has shades of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, and Pierre Bonnard – a dry, mottled canvas from which mother superior stares out at you with an almost-perceptible smirk.

It is far from hagiographic, with just the slightest touch of menace, like a still from the 1947 film Black Narcissus.

The idea that John drifted into solitude along with her newfound Catholicism is not necessarily true either, it had always been a part of her. As a young woman she wrote to Rodin saying, 'I was a little solitaire, no-one helped me or awoke me before I met you.'

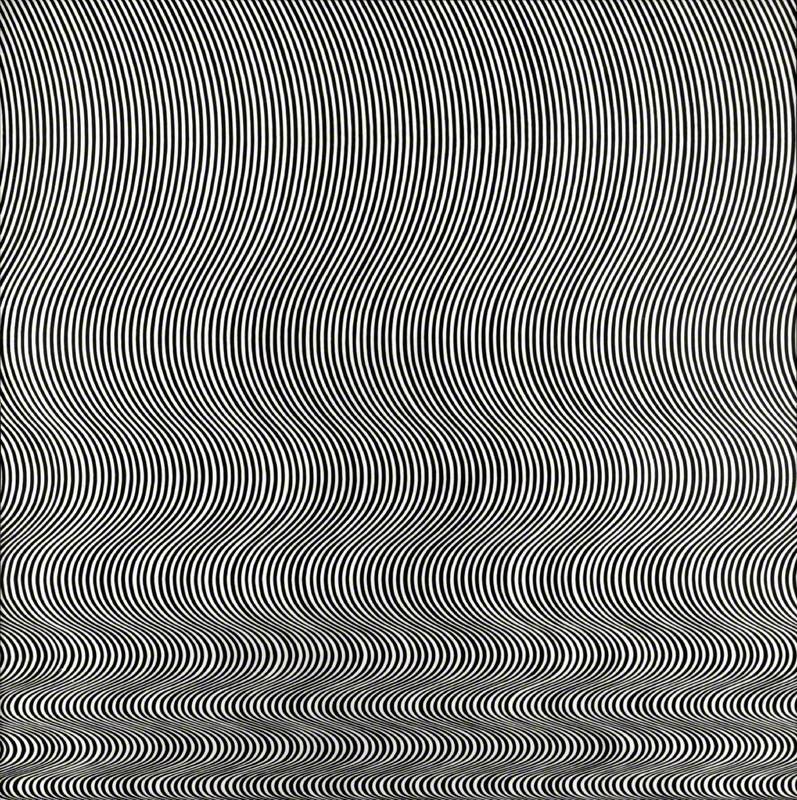

At her bare-walled, dilapidated home in Meudon, John could immerse herself completely in the repetition and rumination of her painting style. When art historian John Rothenstein was granted access to her papers, he found multiple copies that John had made of her own letters. It's exactly how she approached her art: looking back. Reworking. Making new versions of portraits. Redrafting.

Like a novelist, she was always 'editing'. Finding Catholicism gave her a new kind of discipline: a piety toward painting.

'Decide on the subject, before sleeping, for the unconscious mind' she once wrote. It took effort and courage to commit herself to this kind of isolation, to create art from nothingness, to sit with nothing but her memories.

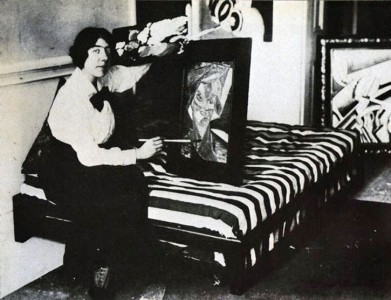

When she studied under James Abbott McNeill Whistler, he would say, 'art is the science of beauty', something John approached literally. Her painting technique was planned out in notebooks, with numbered guides that read like a page in a chemistry paper.

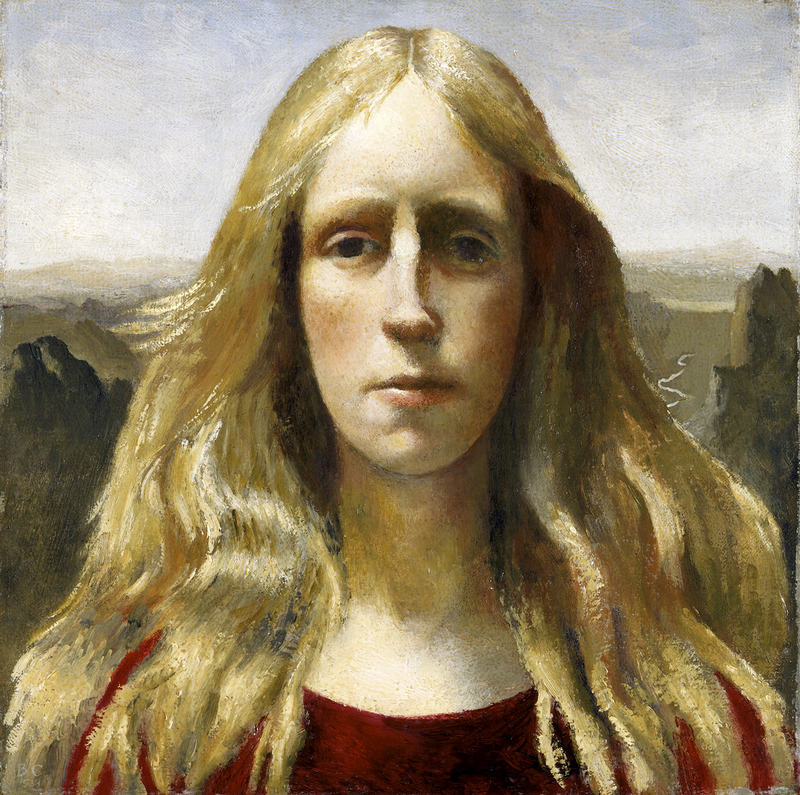

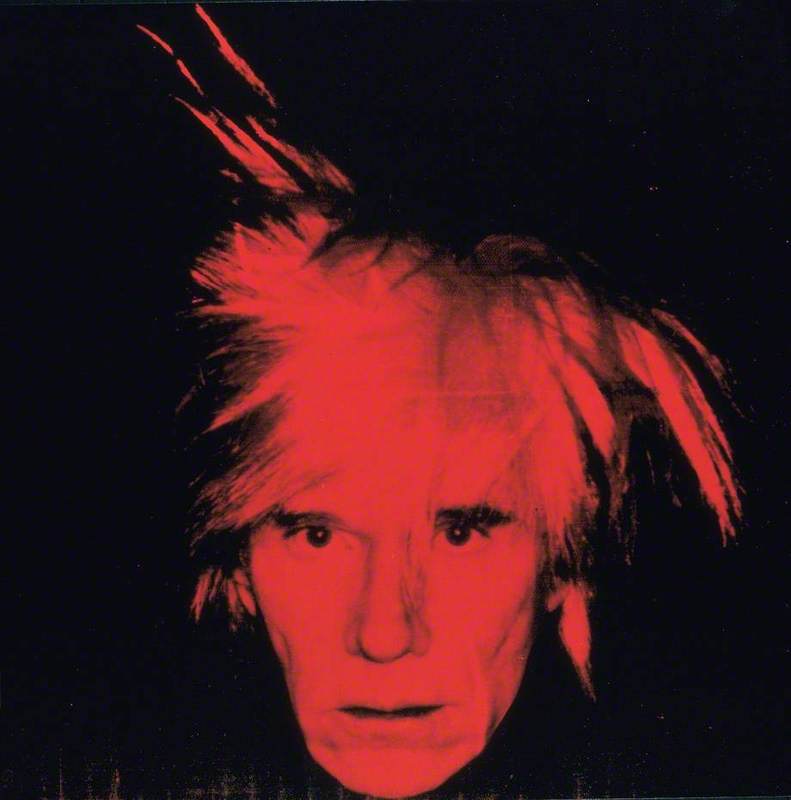

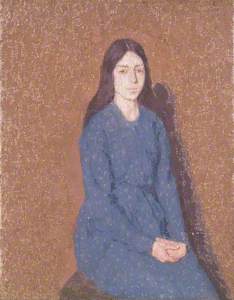

She was never sentimental or twee, but her methodical approach did not rob her paintings of emotion either. The light, chalky palette seen in portraits such as Girl in a Blue Dress makes it feel as though we lived with them for years, like old photographs of grandparents that have been bleached by the sun.

Image credit: Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

Girl in a Blue Dress probably 1914–1915

Gwen John (1876–1939)

Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum WalesTo remove yourself from society doesn't always spell tragedy. For John, isolation was a solution.

There is an obsession with women's choices when they choose to be alone. John's life is often interpreted as a sad tale, though in reality, we have applied our own image of the 'right' way for a woman's life to unfold.

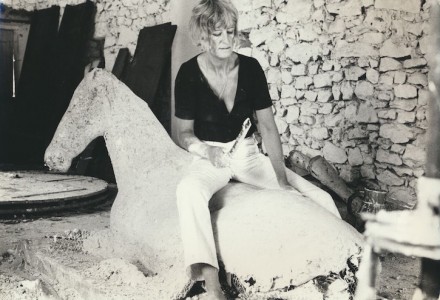

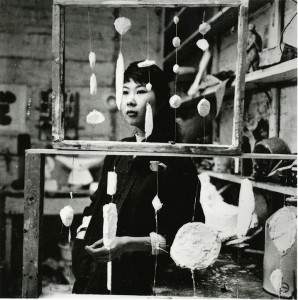

Partial seclusion was her choice, just as it was for abstract painter Agnes Martin when she packed up her life in a pickup truck in the 1960s to go off-grid. Or as it was for Helene Schjerfbeck (sometimes described as the 'Finnish Edvard Munch'), whose adventurous life does not tally with the myth of the artist as a frail but fashionable recluse.

As John's biographer, Sue Roe put it, 'The real mystery of Gwen John's life may turn out to have less to do with her own elusiveness than with the problem of why we find it so difficult to imagine the lifestyle and frame of mind of a woman artist living alone.'

Katie McCabe, author of More than a Muse