In September 1443, Margaret Paston, wife of a Norfolk landowner, wrote to her husband in London. John Paston had been unwell for some time but had begun to recover. To give thanks for John's recovery, and to ensure his continued progress, Margaret wrote that her mother had promised to place an 'ymmage of wax' at the shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham. The 'ymmage' was a wax ex-voto, an object left as a gift for a saint or divinity either in request or in thanks for miraculous favour (in this case John's recovery) granted to the person leaving the object.

Similar objects (below), though likely smaller than those given by Margaret Paston's mother, were found at the tomb of Bishop Edmund Lacy (c.1370–1455) at Exeter Cathedral which was damaged in an air raid in the Second World War. These are the only documented surviving wax ex-votos from England dated to the late fifteenth/early sixteenth century. The Walsingham 'ymmage' wasn't, however, the first wax ex-voto the Pastons had employed in their quest to cure John – another had already been presented at the shrine of Our Lady of Undercroft at Canterbury Cathedral.

Wax votive body part fragments

found at the tomb of Bishop Edmund Lacey at Exeter Cathedral in around 1943

Wax ex-votos were just one part of a much wider votive culture. Votive pledges such as that made by Margaret's mother could take on an almost infinite multiplicity of forms and sizes: building a chapel; commissioning an altarpiece; donating a chasuble; making a gift of commodities or money; leaving a physical token of the misfortune from which the votary had been delivered (for example, shackles, fishbones, tapeworms) and offering wax objects of differing kinds.

Votive offerings have been part of human religious experience since antiquity and continue to be used in the present day. Historically, their use spanned religious and cultural boundaries. They were particularly prevalent among the ancient Greeks and Romans, as well as in other ancient civilisations of the Mediterranean basin. Like many other pre-Christian religious practices, rituals and occasions, votive offerings became interwoven into Christian practice over the centuries.

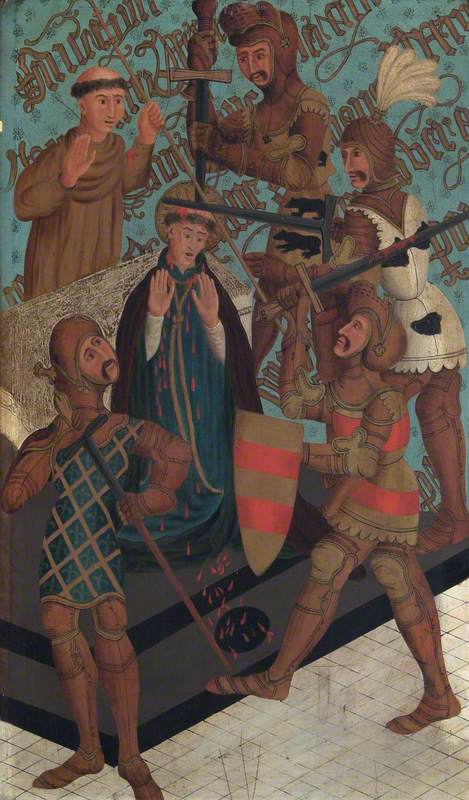

The Oxburgh Retable: Pilgrims at an Altar Begging the Intercession of Saint James

c.1530

Pieter Coecke van Aelst the elder (1502–1550) (follower of)

The terms 'ex-voto' and 'votive' both have their roots in the idea of a vow. The vow was the lynchpin of the agreement made between the votary (person pledging an ex-voto) and the chosen saint or divinity. The votary made a request to a particular saint for divine grace in a situation of extremis (for example, to be freed from captivity or to recover from sickness) and then promised to leave a particular ex-voto in a specific place associated with that saint or significant for the votary. The vow was complete when the votary carried out their promise via the votive act.

In the above scene from the Oxburgh Retable (c.1530), pilgrims, with their distinctive staffs and headgear, are asking for intercession from Saint James of Compostela. In the case of an ex-voto, an important part of that act was placing the ex-voto at the shrine. While some votaries may have been able to place the object themselves, as suggested by the stylised image below, most likely handed over the objects to the clergy in charge of the shrine to make the final placement.

A Man Presenting a Votive Offering to Saint Ferma, Protector of Navigators

Italian School

The Pastons seem to have appealed to the Virgin Mary for help, as they left ex-votos at two shrines associated with devotion to her. As locations to which votaries flocked, shrines dedicated to saints were an important part of votive culture. Reports of ex-votos routinely occur in source material such as letters and inventories, as well as hagiographical accounts from the early medieval period onwards. These accounts functioned as proof of the 'efficacity' of the miracle-working power of shrines and the saints whose relics or remains they held, which in turn attracted more pilgrims. The promise to undertake a particular pilgrimage could in itself be a votive act, although pilgrims might combine it with the leaving of an ex-voto.

Some shrines became renowned sites of pilgrimage because they contained a saint's tomb, such as the tomb of Saint Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral. Becket was murdered in 1170 by four knights who believed they were undertaking the wishes of Henry II, initially a close friend of Becket's before the two became embroiled in a bitter dispute.

A cult soon grew centred on Becket's remains, attracting numerous pilgrims to the site of his death and burial, many seeking his miraculous intervention; 703 miracles were recorded at the tomb by contemporary chroniclers in support of his canonisation. Some of these are depicted in the stained-glass windows of Canterbury Cathedral's Trinity Chapel, which contained the shrine to Becket in the pre-Reformation period. Becket officially became a saint in 1173.

'Miracle Windows' in the south aisle of the shrine of Saint Thomas Becket

Trinity Chapel, Canterbury Cathedral

Others may have possessed relics of one or more saint, such as conserved body parts or items of clothing associated with the saint. Such relics were usually kept in intricately designed reliquaries, such as this sixteenth-century bust of a bishop, which may only have been revealed to the faithful on certain occasions such as saints' feast days.

Some reliquaries were made from high-value materials, such as this reliquary saint from the first decades of the sixteenth century, which was fashioned from gilded silver and blue enamel. Still more shrines, such as Walsingham where one of the Paston ex-votos was destined, were linked to holy apparitions. This shrine had been founded thanks to Richeldis de Faverches, a Saxon noblewoman who received three visions of the Virgin Mary in 1061.

The case of Margaret and John Paston was, therefore, by no means unique. Medieval and Renaissance Christians across Europe frequently deployed wax ex-votos either in request or in thanks for the intervention of their chosen holy intercessor. Margaret describes the ex-voto sent to Walsingham as an 'image', but what did it look like? Perhaps it was a small figure of a man, similar to that of the unique wax ex-voto of a woman standing with her hands held in prayer, which also survives from the Exeter Cathedral bombing.

Wax votive figure of a young woman

found at the tomb of Bishop Edmund Lacey at Exeter Cathedral in around 1943

However, for medieval and Renaissance votaries, likeness and resemblance could mean many things. The term 'image' was equally used in contemporary sources for many different kinds of ex-votos – including those which did not 'look like' the votary in conventional terms. Some wax ex-votos were like the votary in that they were a piece of wax in the same weight or the same height of the individual concerned.

Although wax was a common material for ex-votos during this period, these objects could also be made from precious metals such as gold and silver, base metals such as iron or bronze, a type of what would now be called papier mâché, or even wood. By the end of the fifteenth and beginning of the sixteenth century, votive tablets came into use in continental Europe.

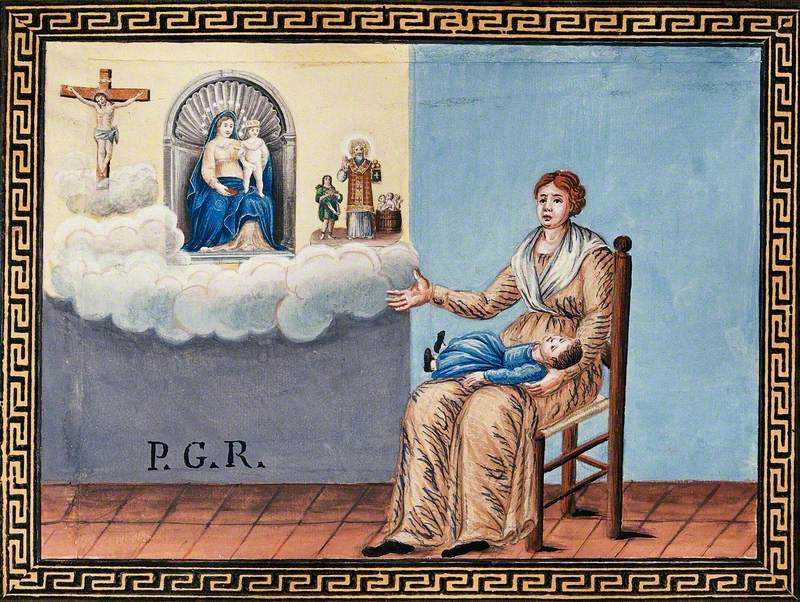

The use of these was particularly widespread in Italy. Such tablets were usually of small format, and depicted the votary's misfortune. In this example, a sick woman suffers in bed, attended to by physicians. In the top right-hand corner floats the Virgin and Child as if transposed from Heaven. These figures represent the sick woman's divine intercessors, by whose grace she has recovered from the illness which has kept her bedbound. Such divine lunettes became a classic feature of votive tablets.

Some Italian versions also include the letters 'P. G. R.', which stands for per grazia ricevuta ('for received grace'), seen in the below example from the late eighteenth/early nineteenth century. These initials symbolise the votive transaction: the votary has received the grace they asked for – salvation from danger or disease – and thus the votive tablet is given in thanks for the answered prayer.

The use of votive tablets continued well into the twentieth century, with photos of the votary or an object (such as a motorbike in the case of a road traffic accident) replacing painted scenes. Their use also became particularly prevalent in Mexico.

A. Votive Rags, Holy Well, Youghal, B. Prayer Tally, Gouganebarra

William Alfred Green (1870–1958)

Although the Reformation halted widespread votive giving in England, the practice continued in Catholic countries. At Gougane Barra in County Cork, for example, a Holy Well attracted hundreds of votive rags, each one attesting to the power of the water (associated with Saint Finbarr) to heal those who needed it. To this day, ex-votos remain in use and feature prominently at pilgrimage sites throughout the world.

Dr Louisa McKenzie, art historian based at the Warburg Institute in London

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation