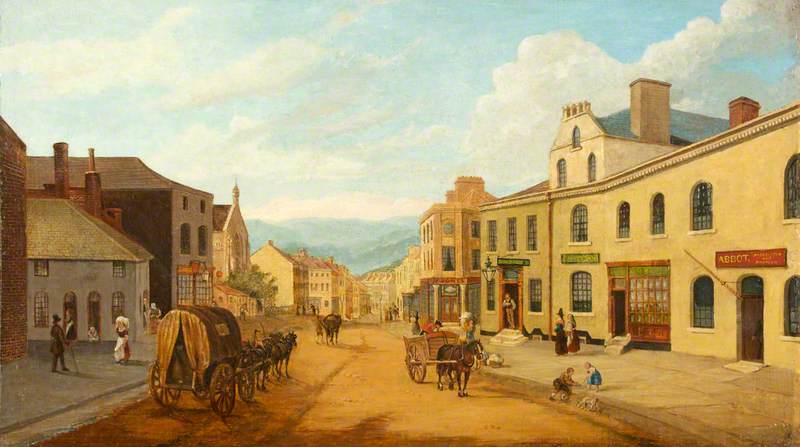

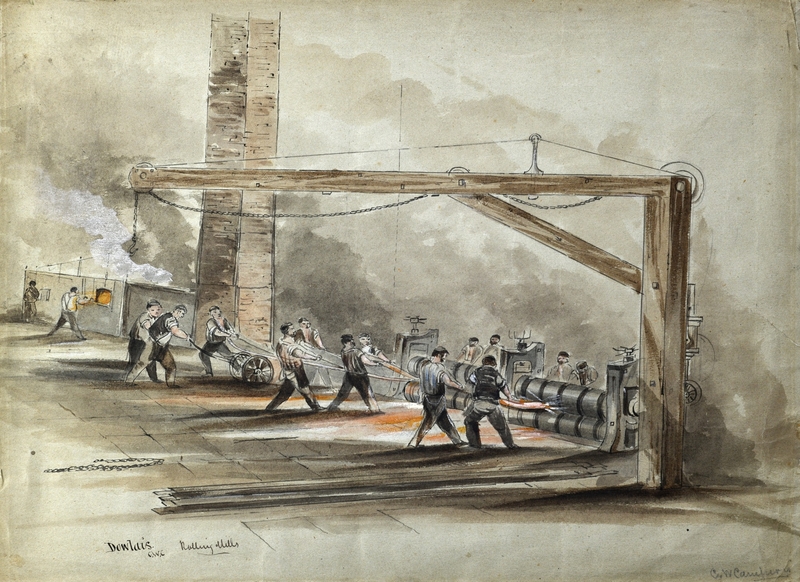

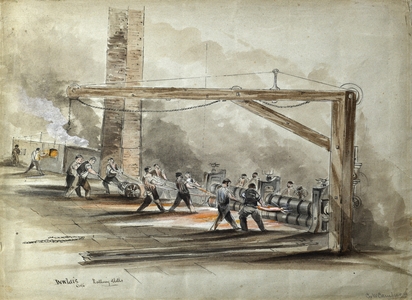

'At Dowlais, in Glamorganshire, where I lived when a child, I heard the roar of the great ironworks day and night in my ears, and I heard the music in the deep thunder of the steam engines and hammers' – Megan Watts Hughes, Pall Mall Gazette, 12th February 1890.

From a young age, Margaret Watts Hughes – or Megan, as she preferred – was fascinated with noises, be they furnaces, hammers, penny whistles or singing. Sound spoke to her: she felt its power, and it came to define her life.

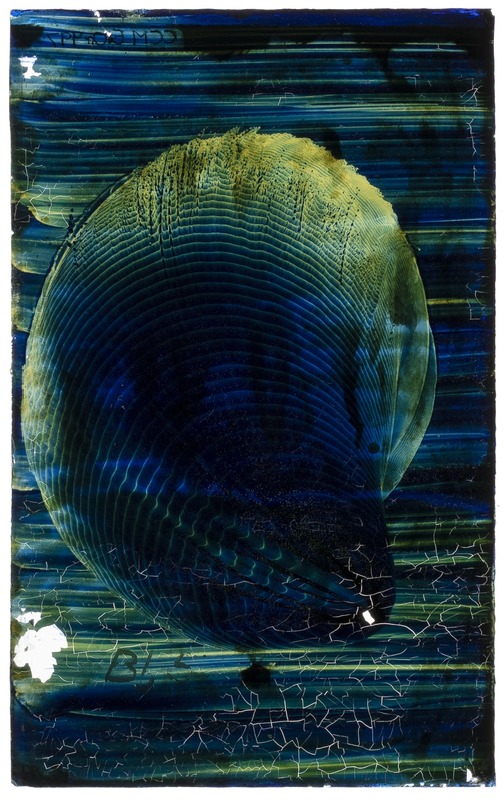

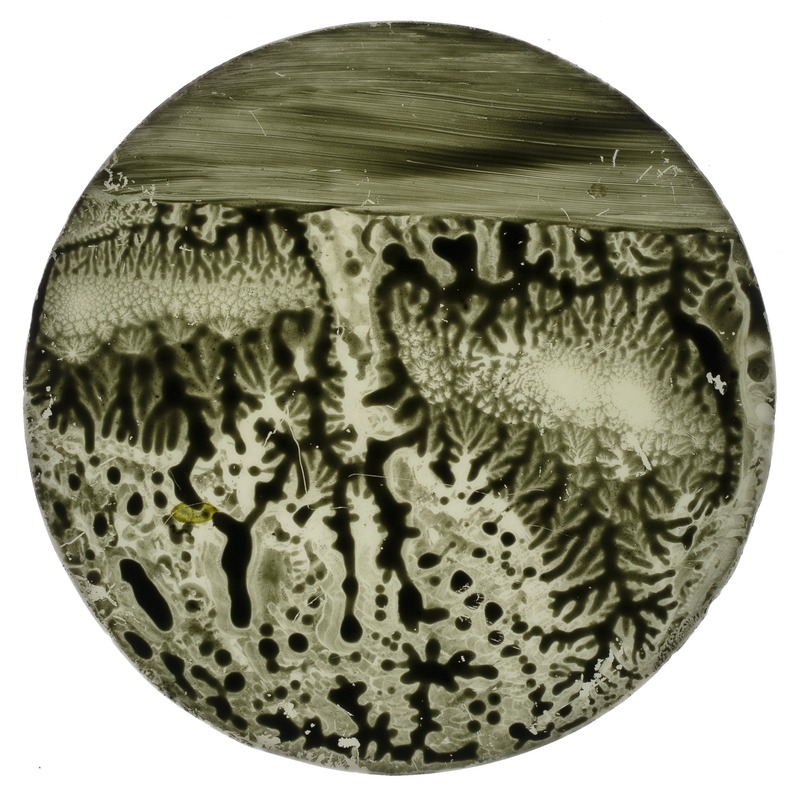

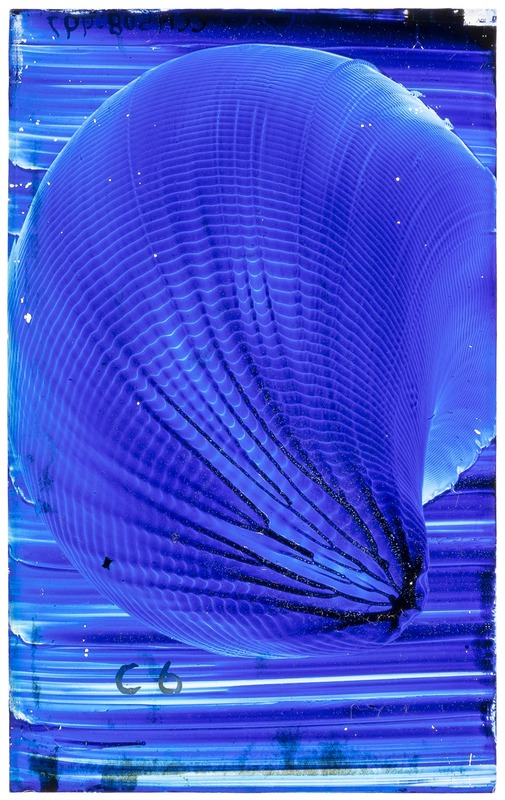

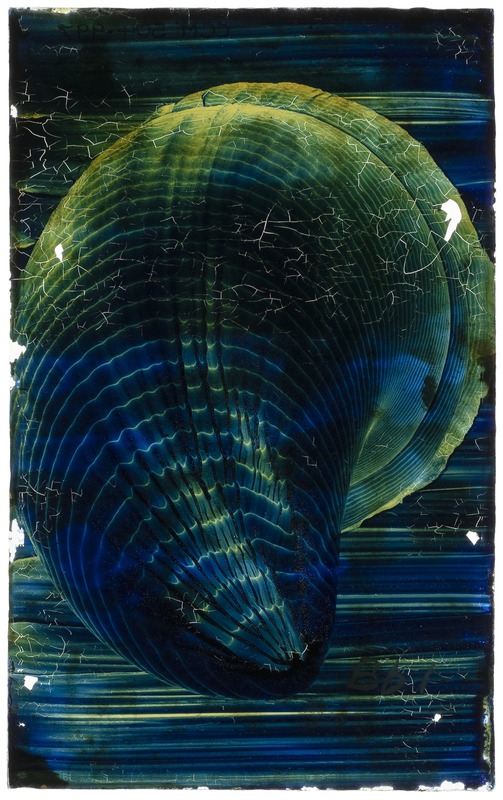

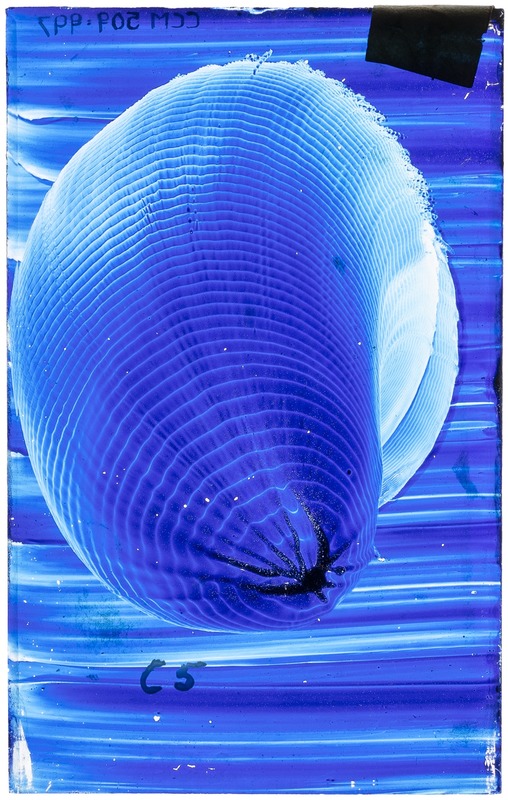

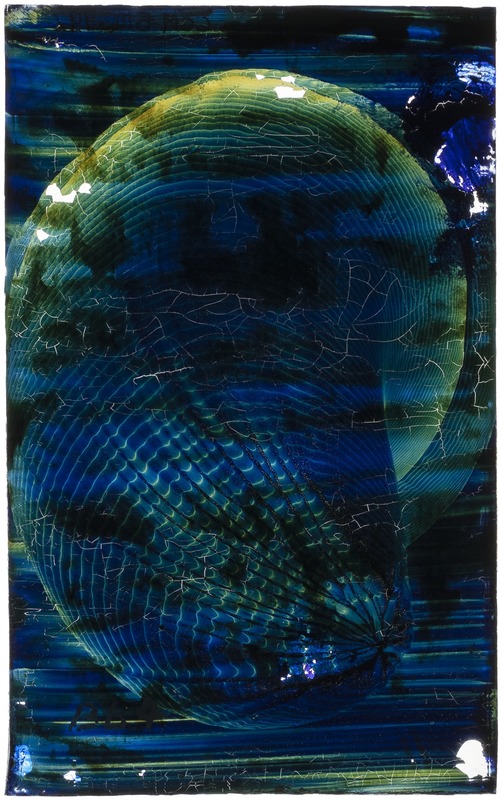

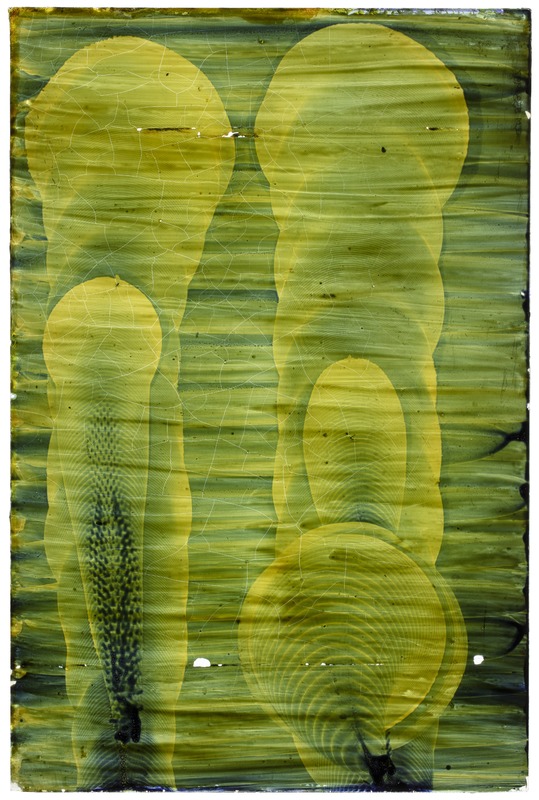

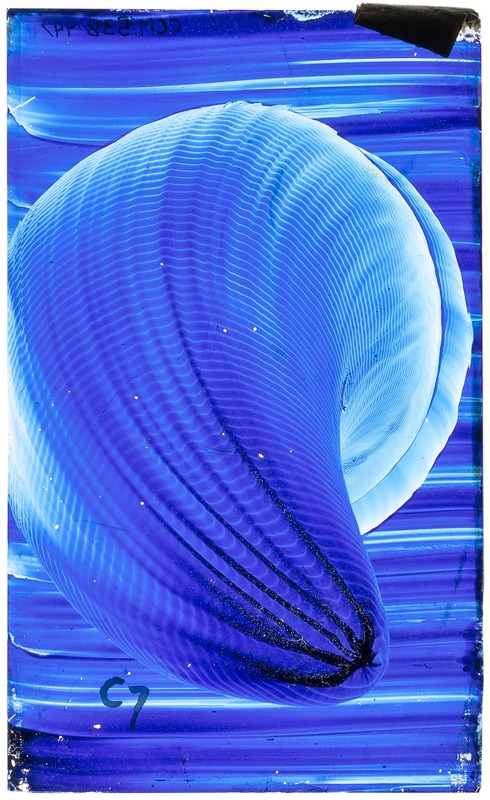

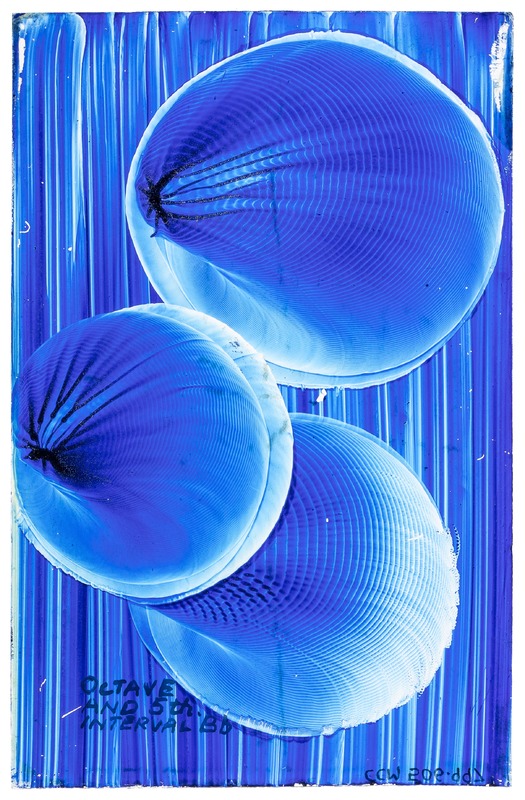

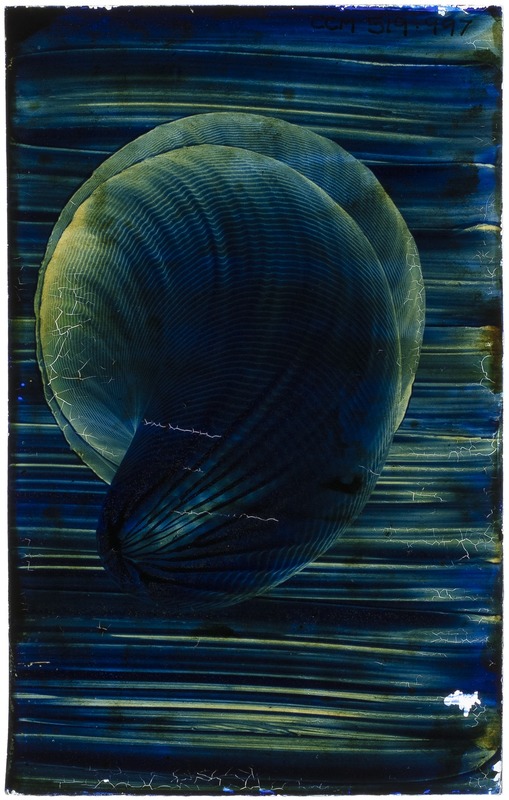

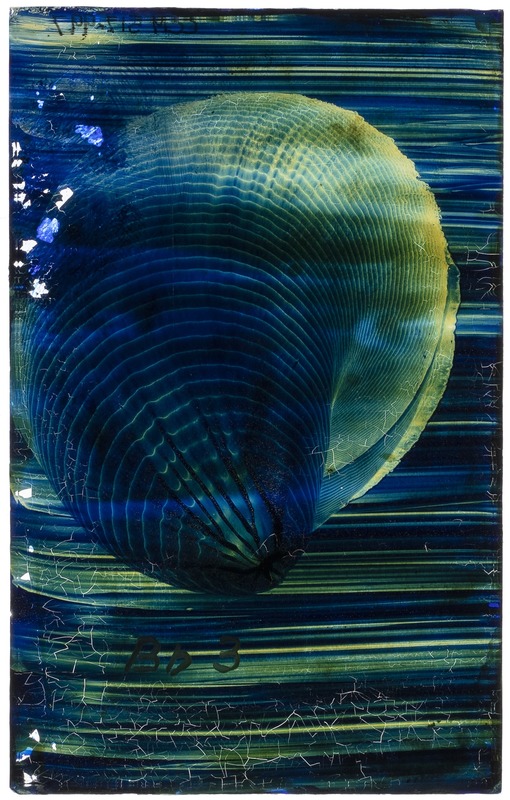

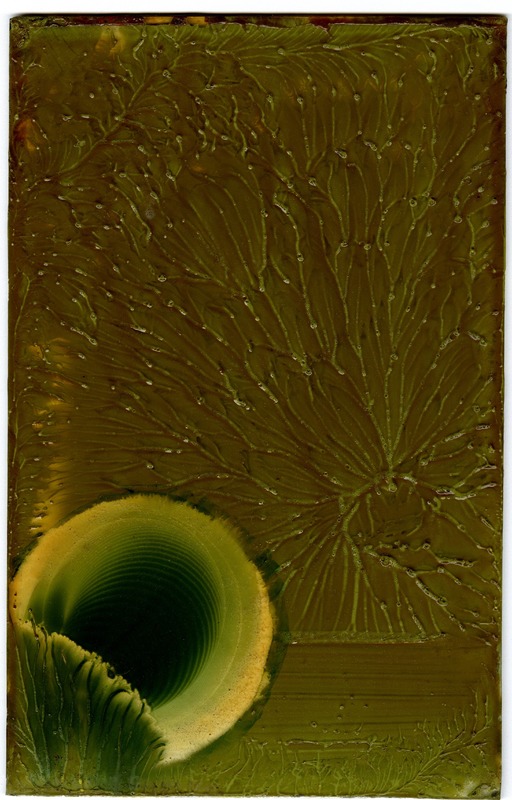

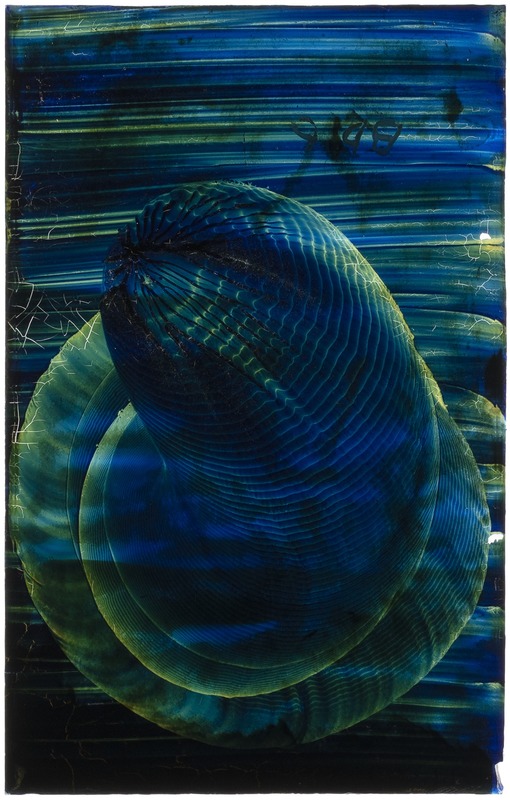

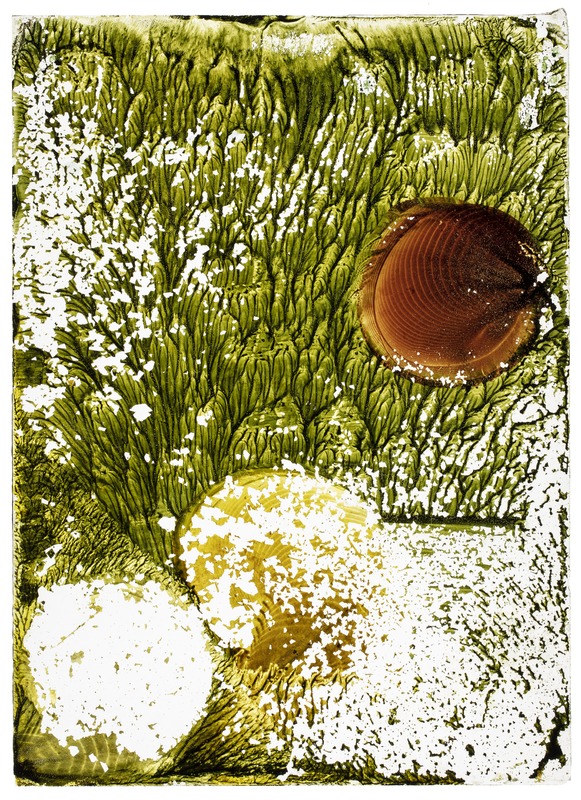

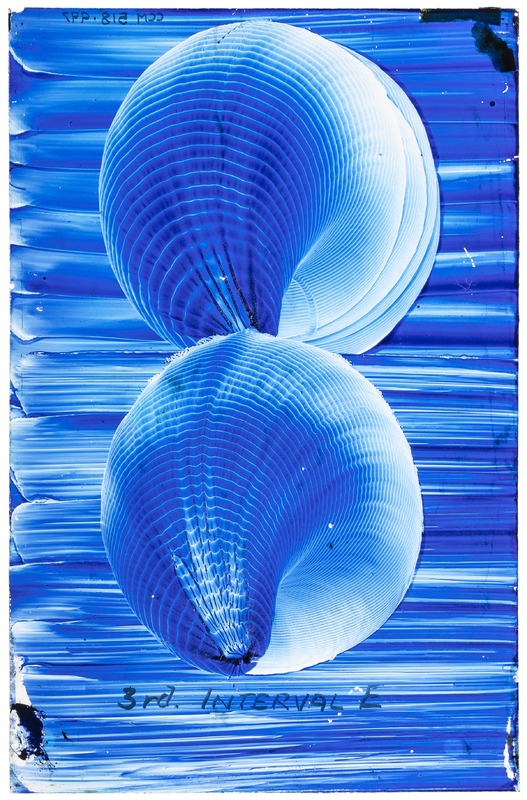

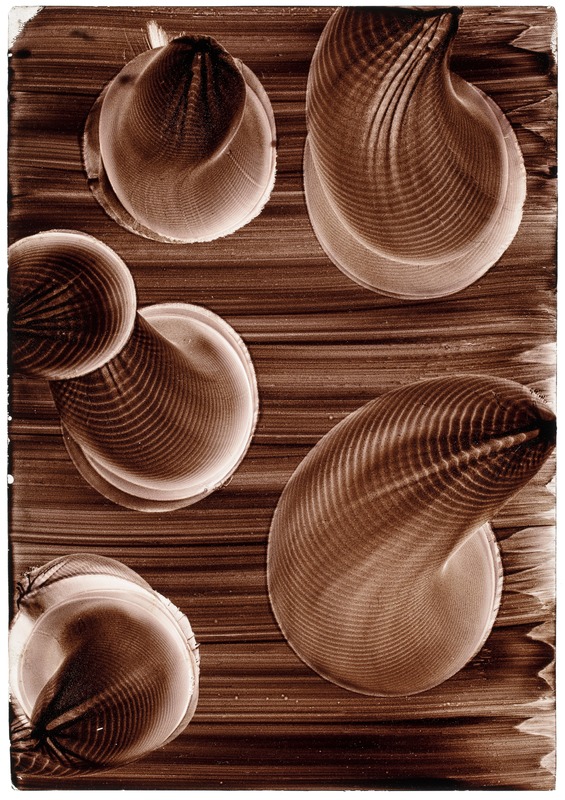

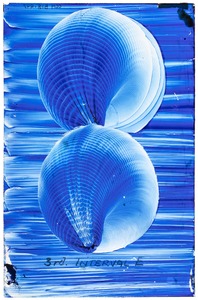

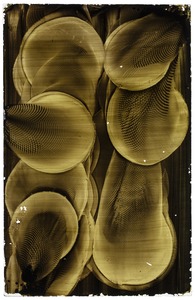

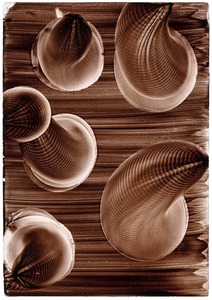

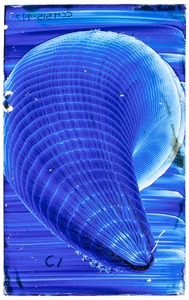

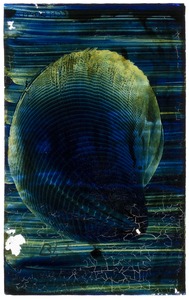

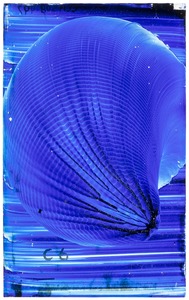

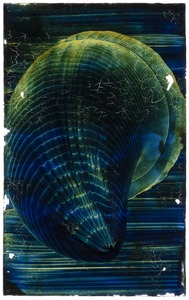

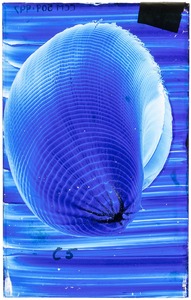

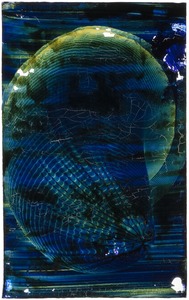

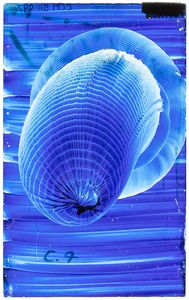

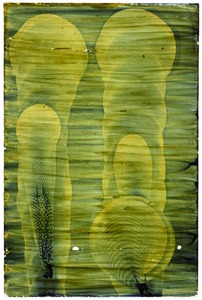

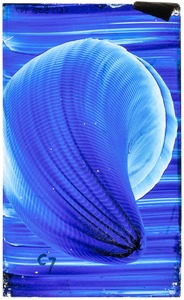

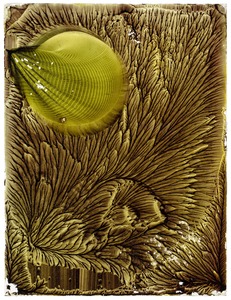

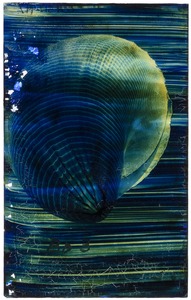

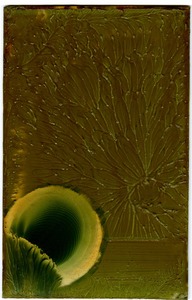

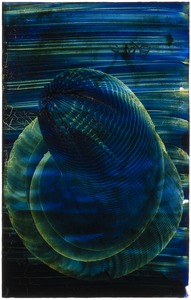

Her relentless ambition to discover the mysteries of sound pushed her to visualise her voice and create an astounding visual record of the human voice. Her 'Voice Figures' caused a sensation in the late nineteenth century. Today they are held in the collection of Cyfarthfa Castle Museum and Art Gallery in Megan's hometown, Merthyr Tydfil. Vibrant, colourful and utterly unique, they bring to life the mysterious world Megan Watts Hughes knew existed but which is invisible to the naked eye.

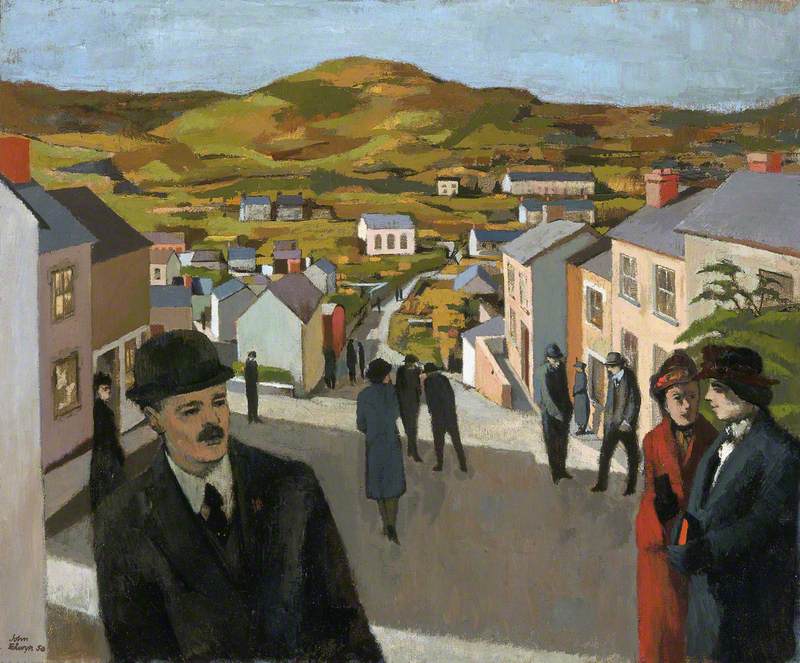

Born in Dowlais, Merthyr, in 1847, Megan was one of eight children. Her family – along with thousands of others – later moved from an agricultural area to the industrial capital of Wales.

Her father, Henry, was one of 7,000 people employed by Dowlais Ironworks in the 1840s. Staunchly religious, the family sang 'sacred songs' all day, every day. The only artwork on the walls of their two-up, two-down stone cottage on Ivor Street was four saintly figures, and the only outings were to the chapel for prayer, socialising and – most importantly – for choir practice.

It was in the Dowlais chapels that Megan's talents were first noticed and nurtured. Her vocal abilities earned her a spot in Dowlais's Number One Temperance Choir. Everyone locally was astounded by Megan's skills, but the family had no funds to further her musical education until the people of Dowlais and surrounding areas stepped in. They raised money and held benefit concerts with the express intention of nurturing this extraordinary vocalist.

The money raised paid for her tutelage at Cardiff, which led to Eisteddfod victories and cash prizes from the Royal Academy of Music. In 1868, Megan made her first stage appearance at St James's Hall in London, a city that eventually became her home. By 1869, she was a student at the Royal Academy of Music and by 1872 she had married Hugh Lloyd Hughes, the deacon of Jewin Welsh Presbyterian Chapel, the oldest Welsh church in London.

Megan believed sound had a hidden power. She was amazed at how impactful song and music were and how they could engage people more than the spoken word. She recounted a story of visiting a woman who had given up on the church. They spoke and read from the Bible, but the woman showed little interest until Megan began to sing passages. Megan saw it as evidence that music had some mysterious power.

A similar thing happened when she began a Bible class in her own home. The children were disengaged until the music began, and the Bible class soon turned into a singing class. When her classes ended, Megan would have to turn the children back onto the streets of London. She could not bring herself to do this, so she turned her home into an orphanage, changing the lives of hundreds of orphaned children.

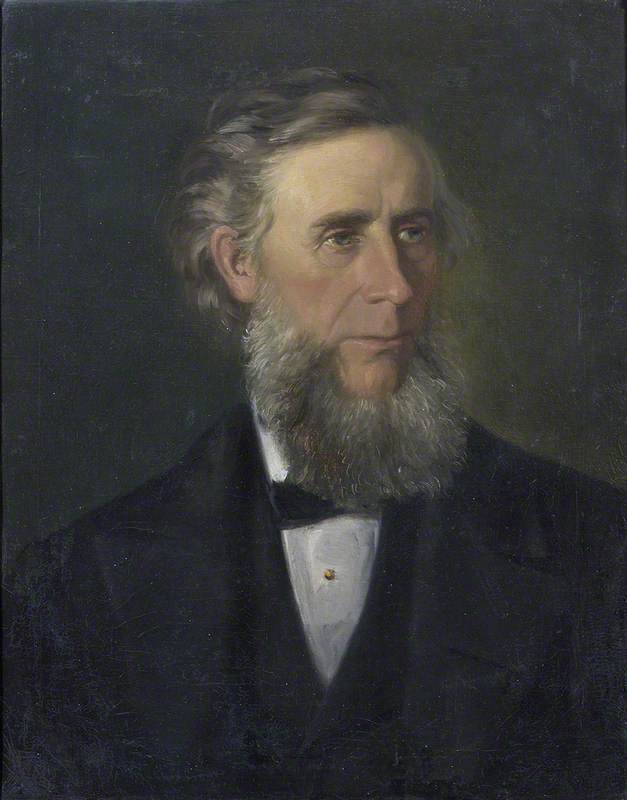

Throughout the 1880s Megan's fascination with music intensified and she began to approach it from a scientific standpoint. She studied the work of scientists who had made discoveries in the world of sound. John Tyndall, Sedley Taylor and Ernst Chladni all influenced her; the latter's experiments visualising sounds hugely influenced Megan's later work.

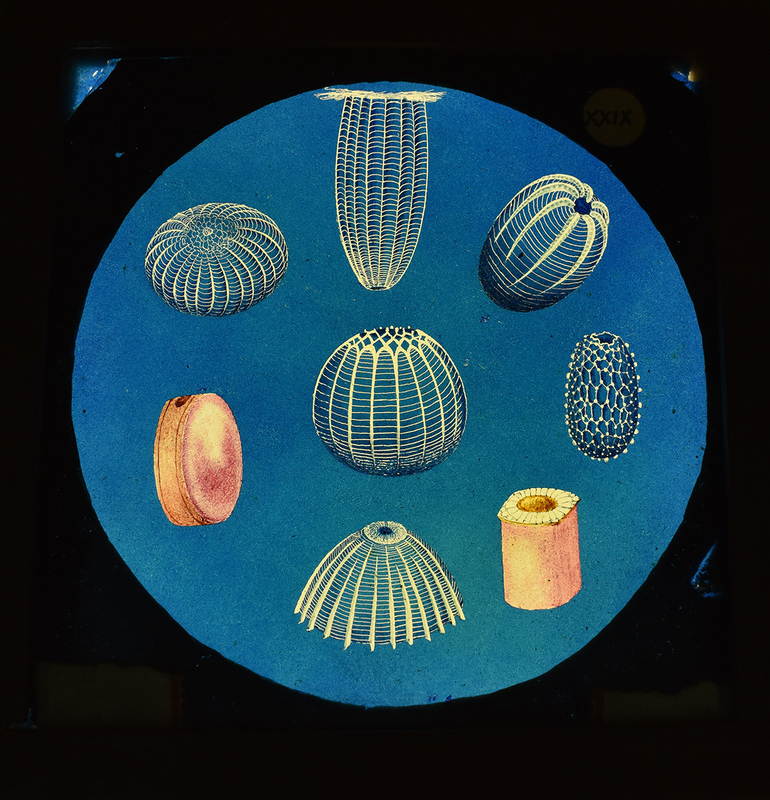

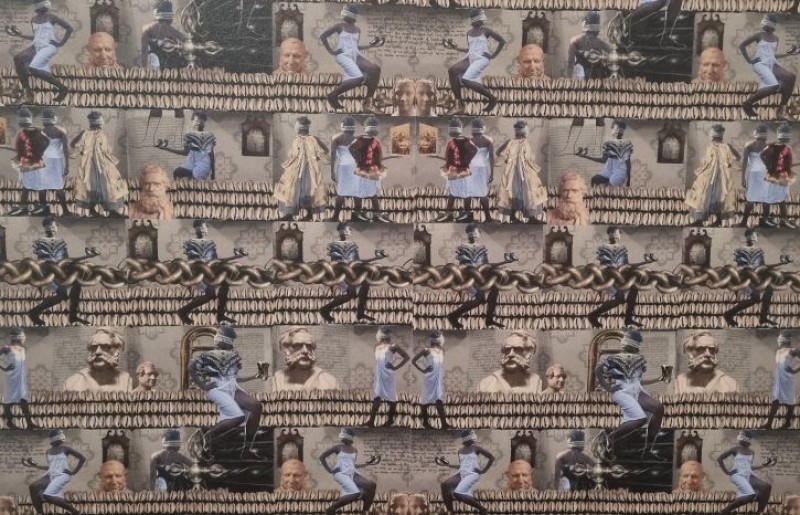

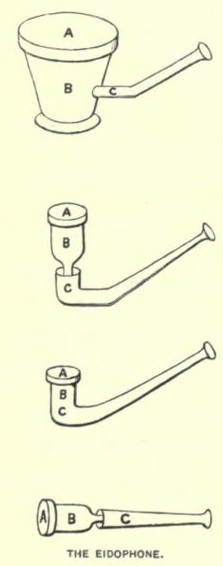

From 1885, Megan began to visualise her own voice. She created a scientific instrument, the eidophone, which she would sing into; it would capture an image of the sound using sand and powders. The materials would react to the vibrations on the elastic membrane, and adding colour allowed Megan to capture the vibrations on glass and ceramic plates. She called the resulting images 'Voice Figures'.

The Eidophone

1891, diagram by Megan Watts-Hughes (1847?–1907) for 'Century Magazine'

She was astonished at how similar the forms produced by the human voice appeared to forms in nature. Figures that resembled ferns, pansies, daisies and trees were just a few of the natural images the human voice could create.

Megan's Voice Figures became a sensation when they were displayed around London, and she was interviewed by many publications who were desperate to discover more. Her discoveries began important conversations among scientists about the significance and importance of sound and its effects on the world.

From the late 1880s onwards, she displayed them at the Musical Association rooms, the Royal Institution and The Royal Society. The Royal Society was a particularly noteworthy display as they only began allowing women to exhibit scientific work in 1876. In 1888 Megan, with her display of Voice Figures and the eidophone, became the first woman to present an invention there.

Megan believed the power of sound was mysterious and spiritual. She, and many Christians of the time, saw her discoveries as a connection to God. Many believed that just as he spoke the world into existence, humans could bring natural shapes and forms into existence, in ways hidden from the naked eye.

Megan hoped her findings linked to God in some way, but she also knew her theories were just that and she was keen to allow her work to be taken to the next stage of scientific experimentation: 'There lies a whole hidden world behind these forms, which the future may perhaps reveal.' (Pall Mall Gazette, 12th February 1890)

Megan died in 1907. Her brother tried to keep her legacy alive by touring the Voice Figures around the UK, but her work became less and less well known, to the point that few have heard of her today, even in her hometown.

There are no recordings of Megan's voice. Instead, her fascination with sound has left behind a visual record: something that is unique to her and shows the varied dimensions of human expression.

Christopher Parry, Digital Learning Officer at Amgueddfa Cymru

Some of Megan Watts Hughes' voice figures are on display in 'Out of this World' at the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery in Swansea from 12th July 2024 to 26th January 2025

The publication of this content was made possible through Welsh Government funding

Further reading

Brewminate, 'Picturing a Voice: Margaret Watts-Hughes and the Eidophone', 2020

Christian Herald Company, Margaret Watts Hughes, The Eidophone Voice Figures: Geometrical and Natural Forms Produced by Vibrations of the Human Voice, 1904

Dr Rob Mullender, 'Divine Agency: Bringing to light the voice figures of Margaret Watts-Hughes', Sound Effects, 8, 2019