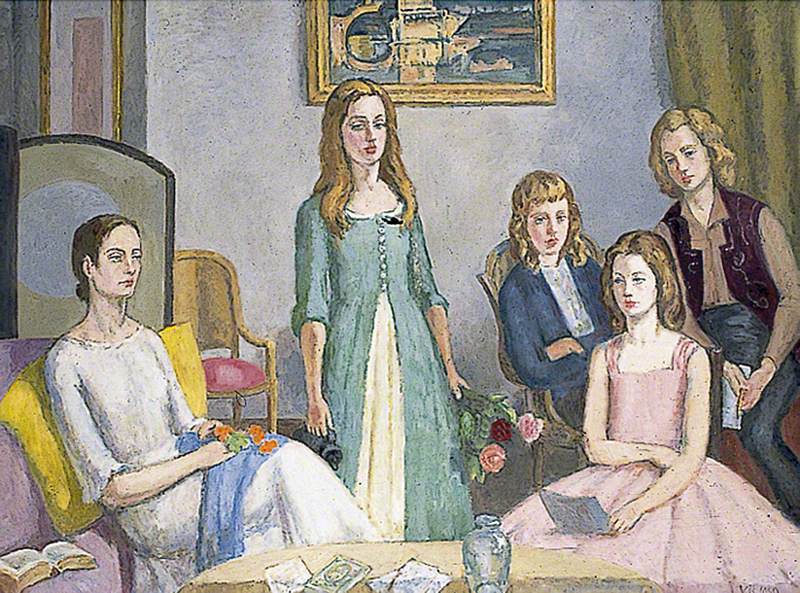

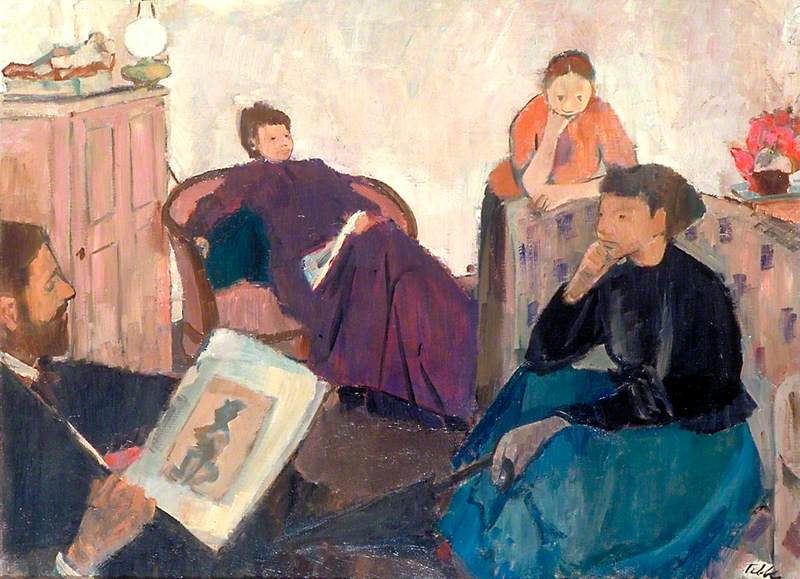

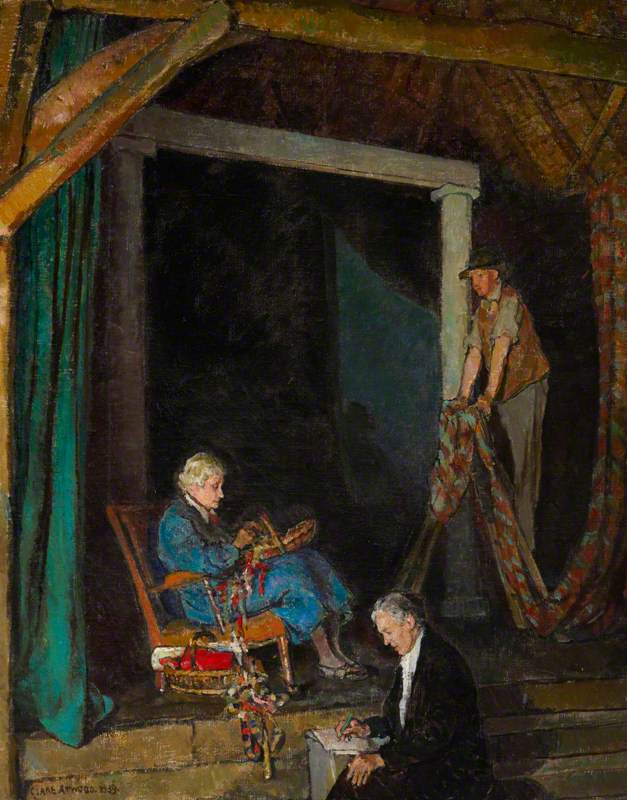

In her painting, The Memoir Club (1943), Vanessa Bell represents a group of middle aged intellectuals who have long-since devoted their lives to three things: intellect, art, and each other.

© estate of Vanessa Bell. All rights reserved, DACS 2025. Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

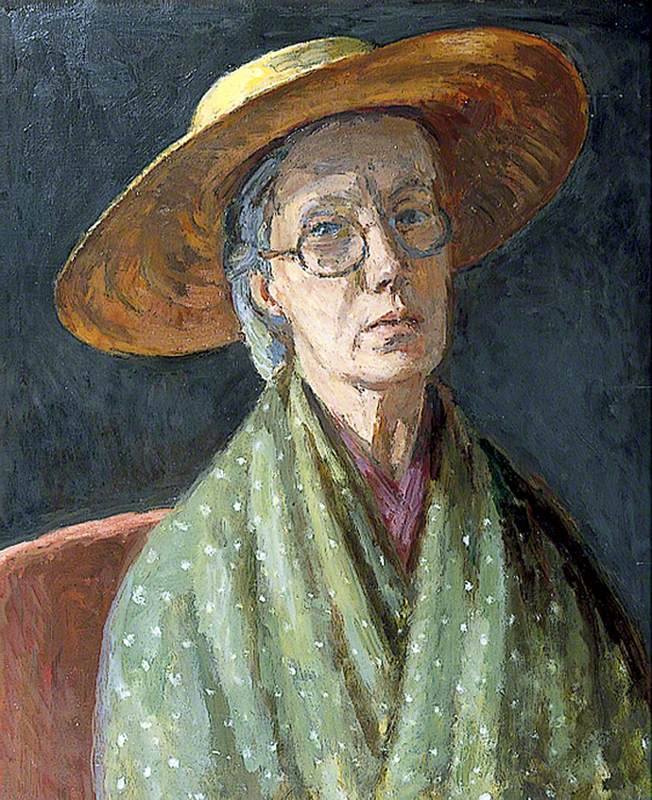

Vanessa Bell (1879–1961)

National Portrait Gallery, LondonSprawled in armchairs, or sharing a sofa, clad in jackets and ties, and even smoking a pipe, the figures themselves would appear conventional, but for Bell's rich palette of blues, pinks, reds and yellow-greens that knit up the sofa-back, cushion the armchair and frame the windows and the painting itself. The brushwork is loose, the figures – on close inspection – dissolve into blocks of colour and light.

Bell's genius is in the distinctive characterisation, achieved in spite of the blurred edges and thickly applied paint; these being typical elements of the post-impressionist style that Bell and her fellow Bloomsbury artists championed.

These figures are recognisable: Bell has caught Duncan Grant's aquiline nose (far left) and Leonard Woolf's narrow austerity (second left); John Maynard Keynes' fleshy face that Virginia Woolf once described as being like 'a gorged seal', and Lydia Keynes' distinctive bright blonde hair (centre couple).

It is a group portrait informed by intimacy, Bell's paintbrush has delineated forms and complexions as familiar to the artist, after three decades of friendship, as breathing, or painting.

In the background are three portraits hung on the plain white walls. These paintings – copies of originals painted by members of the set – memorialise missing participants in the group: Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell's sister, who lost her battle against mental illness two years previously; Lytton Strachey, a celebrated critic and biographer; and Roger Fry, painter and curator of the legendary exhibition 'Manet and the Post-Impressionists' (1910) that brought the British art-world up to date with French developments.

The Memoir Club and the cameo paintings within it, not only commemorate their sitters; they also celebrate the particular stylistic innovations that brought this group so much notoriety and, later, acclaim.

It is the link between emotional sensibility and artistic sensitivity, which came naturally to the Bloomsbury artists, that has led those initially interested in their art to pay so much attention to the complex network of relationships that bound this group together and informed their art. This line of inquiry throws many uncomfortable truths to the fore: criticisms of the Bloomsbury artists have cycled through their snobbery, exclusivity, and self-congratulatory egoism (they formed a club to write their memoirs in their very early middle age).

In their own time the Bloomsbury Group made enemies. Wyndham Lewis included them as targets in his rambling and bitter satirical novel, The Apes of God (1930), about the London art world. Today, we are disinclined to forget the huge privileges that the Bloomsbury artists were born into, and which made their pursuit of bohemia possible.

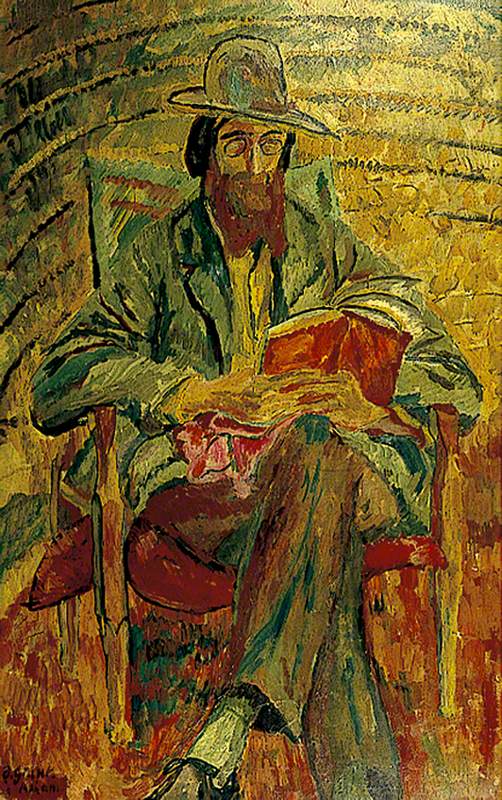

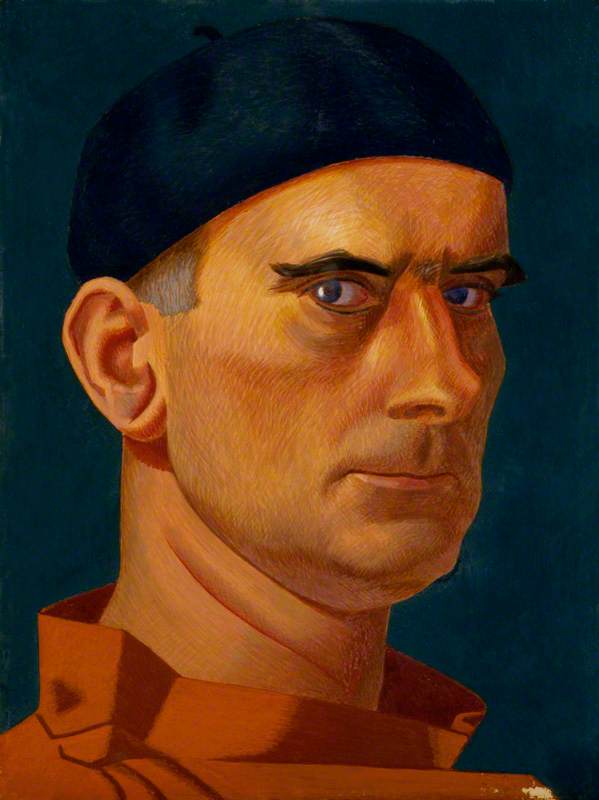

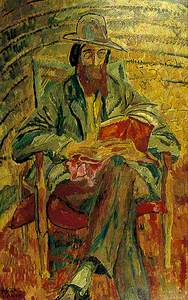

In his portrait of Lytton Strachey that hangs on the wall in The Memoir Club, Grant painted his cousin and sometime lover with a humorous eye, creating a likeness so informed by the sitter's idiosyncrasies that the result is nearly a caricature.

Grant has clearly taken on board the lessons of Vincent van Gogh, who was exhibited at the Manet and the Post-Impressionists exhibition three years previously. Van Gogh's streaky brushwork, by which textured blocks of colour are created out of a series of visible brush-strokes, is present in Grant's work, as are the distinctive black outlines that are associated with Van Gogh.

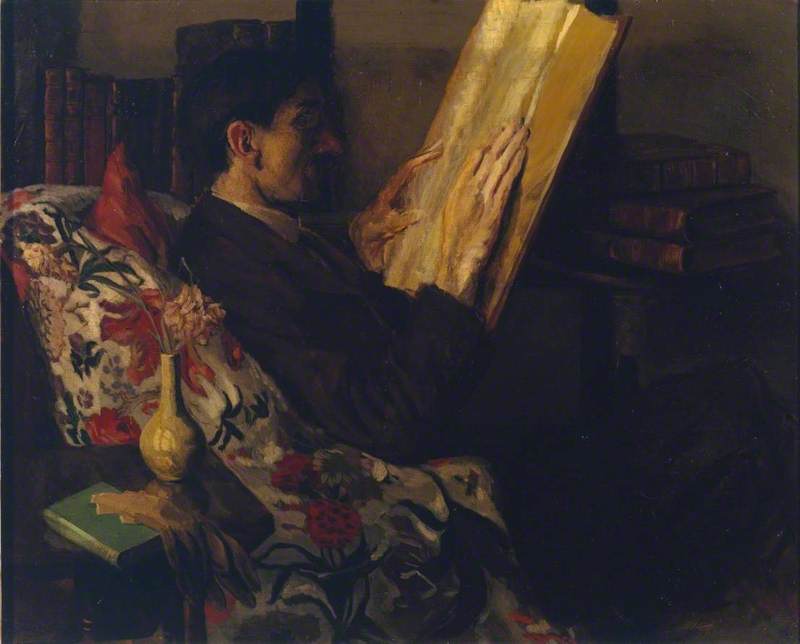

The painting is very different from Grant's earlier portrait of Strachey, dating from a couple of years before Fry's first post-impressionism exhibition.

The earlier portrait also represents the sitter busy with a book, but the deep shadows and play of light are reminiscent of nineteenth century Academy paintings and the work shows no hint of Grant's later style.

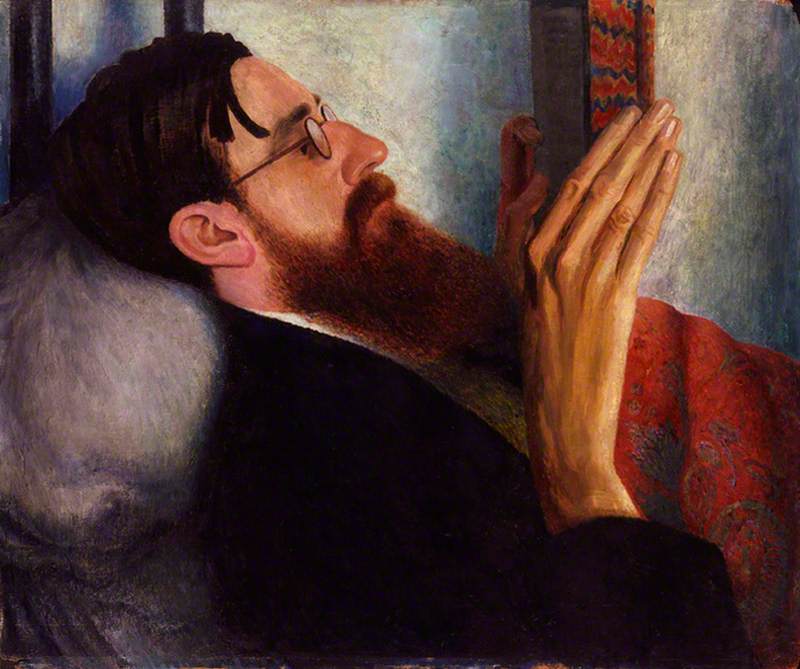

However, this painting did gain some sort of second life. Dora Carrington, an artist who lived with Strachey up until his death, must have been influenced by Grant's early portrait when she painted her own portrait of her lover: the pose is very similar, as is the prominence of Strachey's distinctively long, narrow hands. Yet Carrington has interpolated these features into a work of a very different style, her painting is more colourful, flat and decorative.

Duncan Grant was himself the subject of similarly sentimental, yet innovative, portraiture. Vanessa Bell's double portrait of the two fathers of her children is deeply moving, not only because of the way that Bell has tamed a riotous range of colours into a peaceful harmony, but also because of the specific domestic contentment that Bell is portraying.

© estate of Vanessa Bell. All rights reserved, DACS 2025. Image credit: Birkbeck, University of London

Interior Scene, with Clive Bell and Duncan Grant Drinking Wine

Vanessa Bell (1879–1961)

Birkbeck, University of LondonBell was married to Clive Bell until her death in 1961 and had two sons with him. However, early in their marriage Bell fell in love with Grant, and despite his usual homosexuality, had a child with him. Grant joined the Bell household, living with Vanessa and Clive and their children for several years. Bell's affection for the two men and their casual manner with one another, surrounded by a clutter of wine and books, are charmingly apparent in the portrait.

Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, between them, also turned their affectionate eye on their family. Angelica Garnett, their daughter, was the subject of a series of paintings by her parents that trace her growth from child to adult and mother.

Grant's painting of his daughter playing the violin places the sitter against a richly patterned backdrop that was the Bell's preferred style of interior decoration. Only a couple of years later, Angelica would meet her future husband, David Garnett, who had been a young friend and sitter of her mother's, and a lover of her father's.

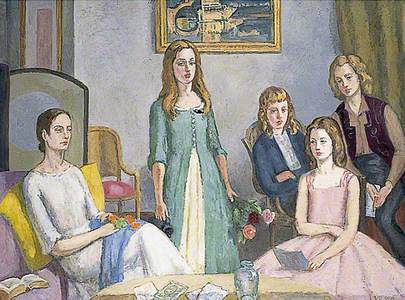

Many years later, a full decade after The Memoir Club, Bell painted a group portrait of her daughter and granddaughters, which, unlike The Memoir Club, depicts its sitters facing out to the viewer, less an exclusive social club, than an open, affectionate family.

The Memoir Club portrait exemplifies the unique blend of absolute intimacy and creative bravery that typified the character of the Bloomsbury set. The portrait seems to have been the preferred mode of the Bloomsbury artists; perhaps because it was the most appropriate art form for artists whose work was encouraged by, and fed back into, their relationships with one another.

Painting and loving, for these artists, seem to have been symbiotic creative processes. Indeed, Vanessa Bell's sister, Virginia, a writer who dabbled in painting as a teenager, wrote a novel that pivots around the connection between painting and feeling. To the Lighthouse concludes with a character simultaneously painting a coastal scene and realising that she loves a man whose boat is traversing her perspective. As painting, realisation (and book) are completed, Woolf writes: 'Yes, she thought, laying down her brush in extreme fatigue, I have had my vision.'

Victoria Ibbett, Art UK volunteer