Celebrated internationally for the large-scale abstract paintings he produced from the late 1950s, two exhibitions at the Millennium Gallery, Sheffield and one at the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds draw attention to a playful group of ceramic sculptures John Hoyland made in 1994, commissioned by Christie's Contemporary Art and first shown that year.

© the artist's estate. Image credit: The John Hoyland Estate

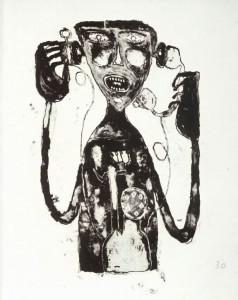

The World

1994, ceramic by John Hoyland (1934–2011)

Superficially anomalous in the scheme of his wider work, their hieroglyphic forms reveal a language through which his painting might be decoded. And yet, located in conversation with installations by Phyllida Barlow, Hew Locke and others, the importance of 'these mad little hybrids' – as Hoyland referred to the 25 creature-like 'beings' – becomes apparent. Not merely interventions, they are standalone, powerful works of art with lives of their own.

© the artist's estate. Image credit: The John Hoyland Estate

The King

1994, ceramic by John Hoyland (1934–2011)

Together, 'These Mad Hybrids' and 'Strange Presence' at the Millennium Gallery, and 'Imaginary Beings' at the Henry Moore Institute reevaluate Hoyland's work from this perspective. Initially grounded in the High Modernist tradition, the Sheffield-born artist absorbed sculptural influences from his London contemporaries (notably Anthony Caro). Although remaining dedicated to painting throughout his career, they formed a thread shaping its structure, balance and composition.

Also sympathetic with Picasso, Hoyland felt that the Cubists' paintings were 'blueprints for sculpture'. For Sam Cornish, curator of The John Hoyland Estate, the 'hybrids' fully realise this sentiment, seeming 'to be pulled out of the limited space of painting into three dimensions'. This is clearly evident in the structural relationship between Maverick Days (1983) and Ocean Man (1994).

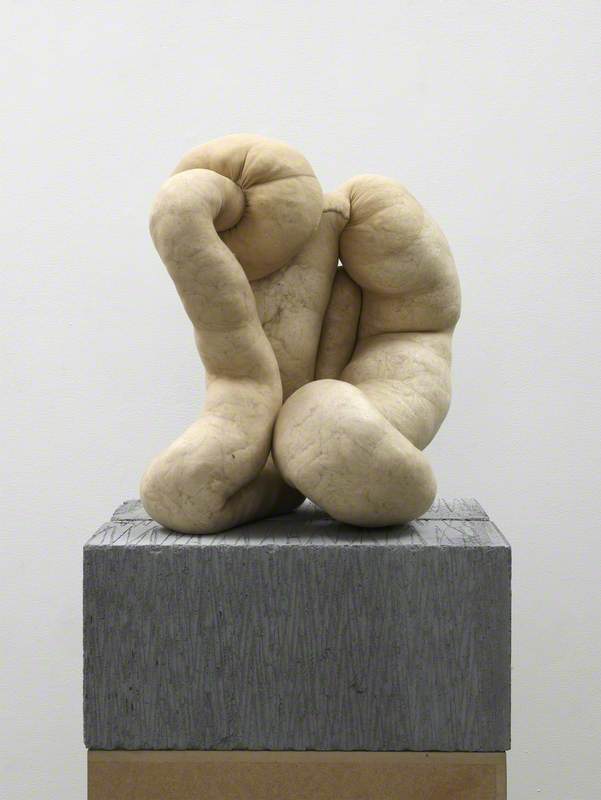

© the artist's estate. Image credit: The John Hoyland Estate

Ocean Man

1994, ceramic by John Hoyland (1934–2011)

However, while explicable as outcomes of his painterly exploration, drawing upon imagery from the years preceding their creation, the ceramic works do not need to be interpreted solely within the trajectory of Hoyland's career. The current iteration of 'These Mad Hybrids', which previously featured at RWA Bristol (February to May 2024), has adopted a new curatorial approach.

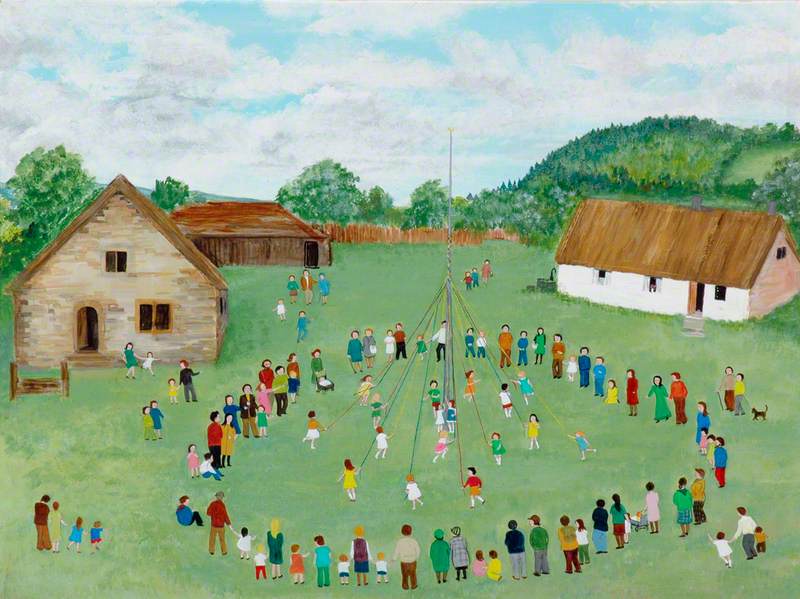

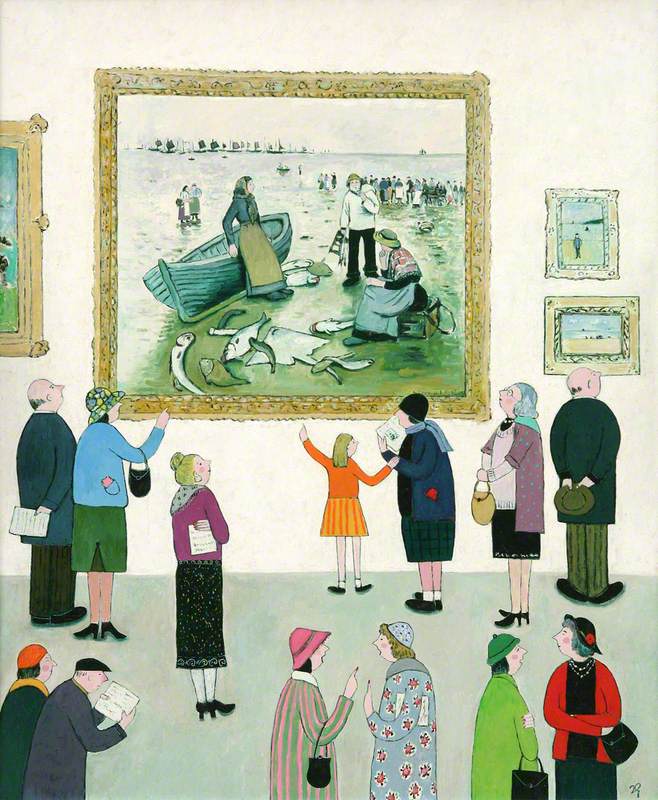

Where the first exhibition included paintings alongside the sculptures, this is no longer the case. 'Strange Presence' focuses on Hoyland's acrylic adventures in an adjacent room, while in the main gallery, the hybrids are arranged on two tables at opposite ends of the space, competing for attention with otherworldly entities united by their bold colouration and anthropomorphic forms. The unfolding scene suggests movement, animation and telepathy.

Image credit: Sheffield Museums

'These Mad Hybrids' exhibition at the Millennium Gallery

Through their curation, artist (and former studio assistant to Caro) Olivia Bax, Wiz Patterson Kelly (editor of the catalogue raisonné at the Hoyland Estate) and Sam Cornish, assert the hybrids' deserving place within the contemporary sculptural landscape.

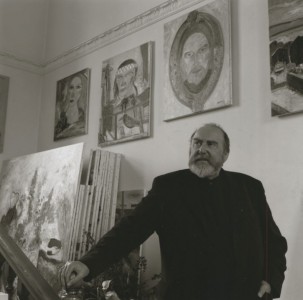

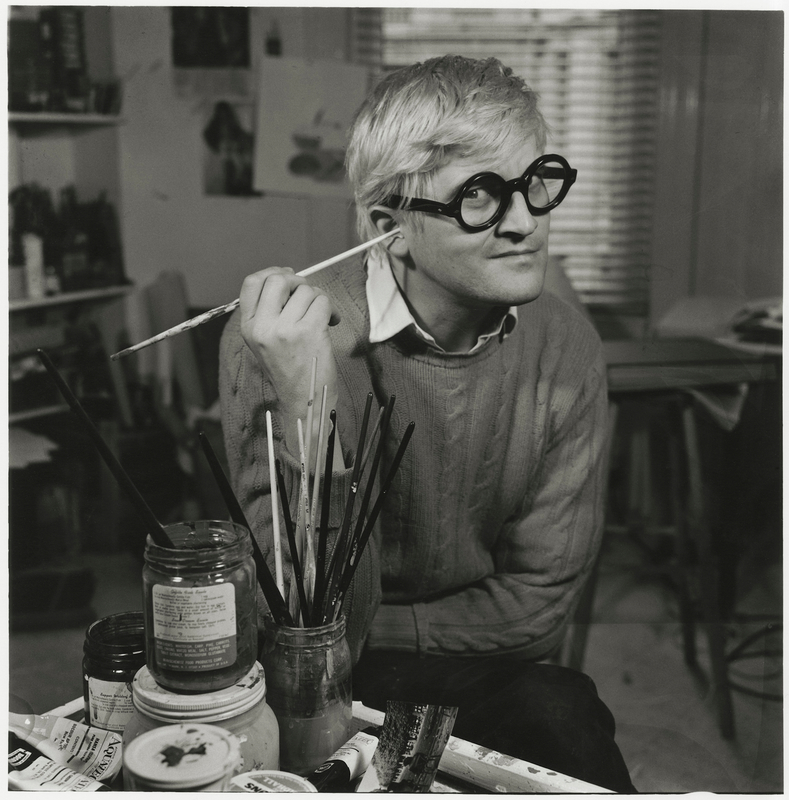

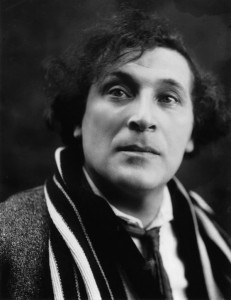

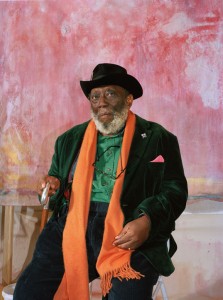

Image credit: Nick Smith

John Hoyland in his studio, July 2010

At the Henry Moore Institute, where four of Hoyland's sculptures are exhibited alongside an equal number of his paintings, this attitude is reinforced, with no hierarchical dominance afforded to any given piece. Leeds Art Gallery's recent acquisition of Sun Animal and Sorcerer, both featured within 'Imaginary Beings', confirms the significance of the ceramic works.

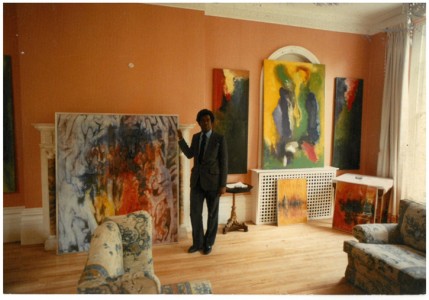

First experimenting with sculpture as a young child, Hoyland created figurines out of plasticine and glitter wax, and trees out of twigs for them to climb. Perhaps unwittingly, these naïve, human-like creatures anticipated the hybrid nature of his mature work, and non-conformist approach to making art.

Image credit: Sheffield Museums

'These Mad Hybrids' exhibition at the Millennium Gallery

If for Clement Greenberg, the influential art critic and advocate of abstract impressionism, High Modernist painting was defined by a sense of purity and the casting aside of artefacts alien to it, Hoyland rejected this stance, believing both that painting could be sculptural and sculpture could be painterly.

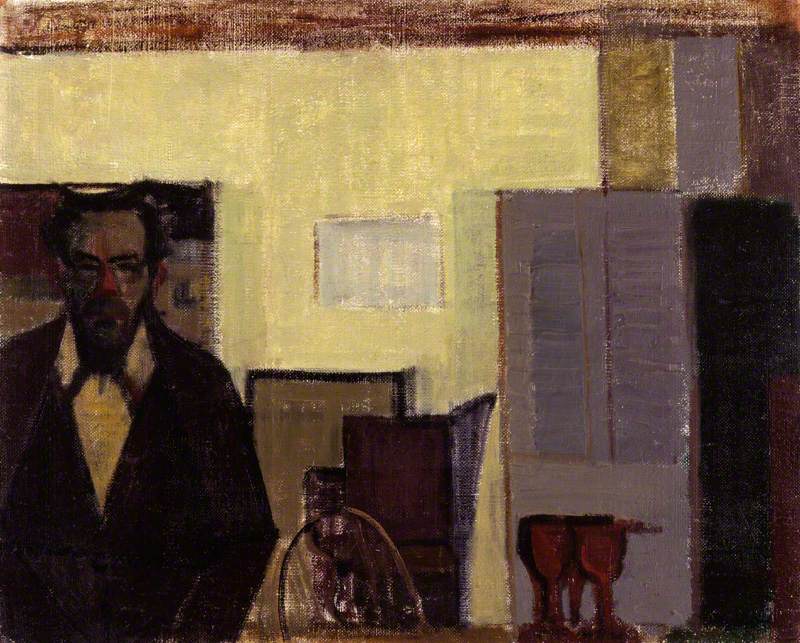

By the 1980s, at a time when he was moving away from the geometric forms and vertical structures which defined his earlier work into a more expressive and cosmic realm, the resulting offerings resembled 'stacked sculptural units', according to Cornish. These increasingly incorporated triangular and circular shapes suggesting contorted limbs and faces, perhaps alluding to a new influence – Borges and Guerrero's The Book of Imaginary Beings – a compendium of mythical beasts.

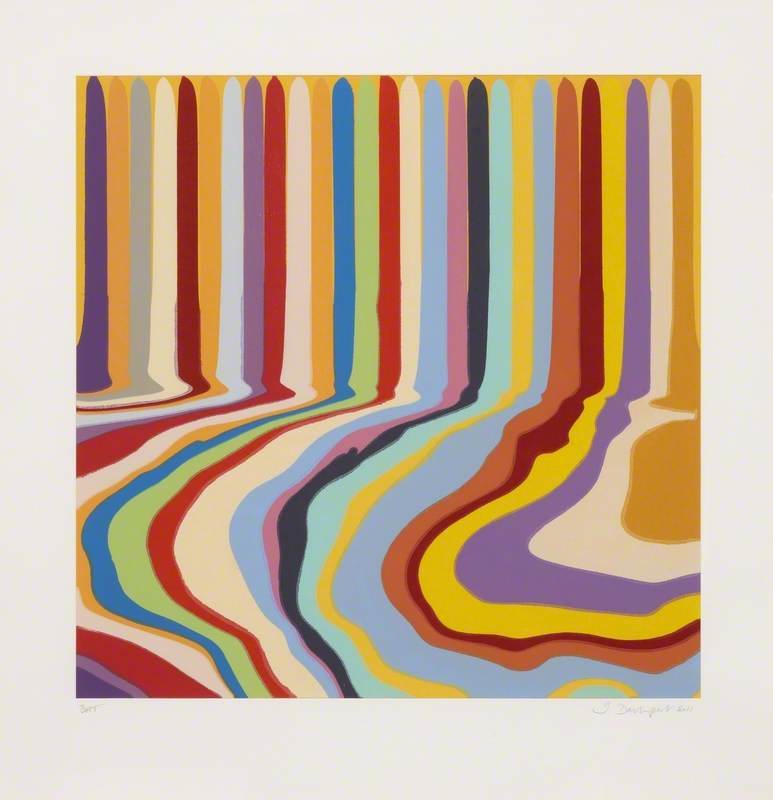

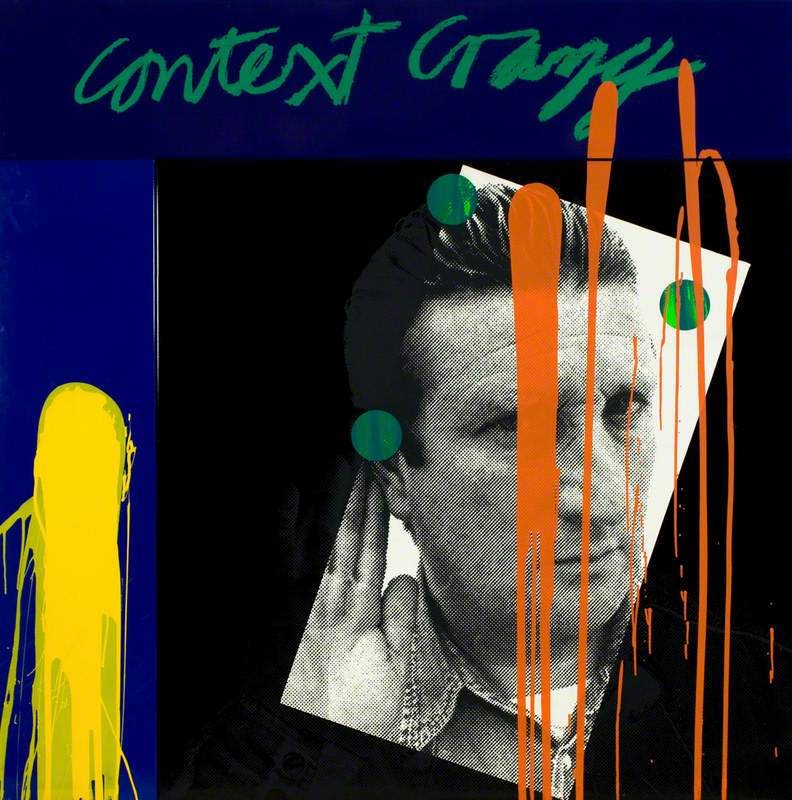

Image credit: Sheffield Museums

'Strange Presence' exhibition at the Millennium Gallery

Arvak, painted the year before Hoyland created his ceramics and on show in 'Strange Presence', is emblematic of this new direction. A surreal, abstracted figure traverses a psychedelic plain, foretelling the work that would follow.

The anarchistic energy of the painting suggests a sense of freedom and humour which his previous output lacked, and which the hybrids would amplify. With no imperative to engage in a formalised process demanding calculated outcomes, the artist enjoyed the unpredictable nature of ceramics, which yielded unexpected results emerging out of firing (most notably to do with colour).

Image credit: Sheffield Museums

'These Mad Hybrids' exhibition at the Millennium Gallery

On viewing Hoyland's sculptures, these themes manifest in several striking ways. Firstly, unlike his often-monumental paintings, the hybrids are small-scale, most no larger than a table lamp. Their size and close proximity to each other simultaneously suggest a sense of fun, awkwardness and community – these small creatures are like alien pets, materialised from another dimension. Dragon, a shrunken prehistoric animal explores its habitat, while Ocean Man and Ruler appear to survey the gallery though painted eyes.

Image credit: Henry Moore Institute, Leeds

'Imaginary Beings' exhibition at the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds

Secondly, unlike the relative precision with which his pre-1980s work was completed, the sculptures are crude objects crafted without the same attention to detail. The hybrids seem to possess free-spirited personalities which reflect Hoyland's carefree approach to the layering of paint onto their surfaces.

Image credit: Sheffield Museums

'These Mad Hybrids' exhibition at the Millennium Gallery

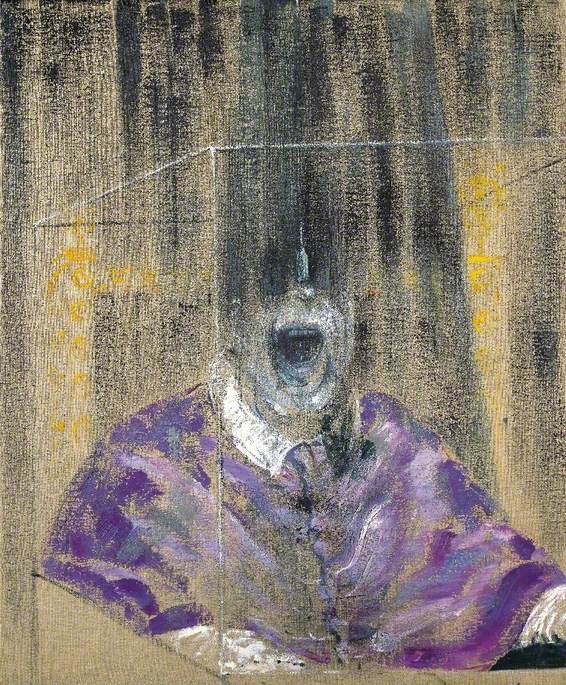

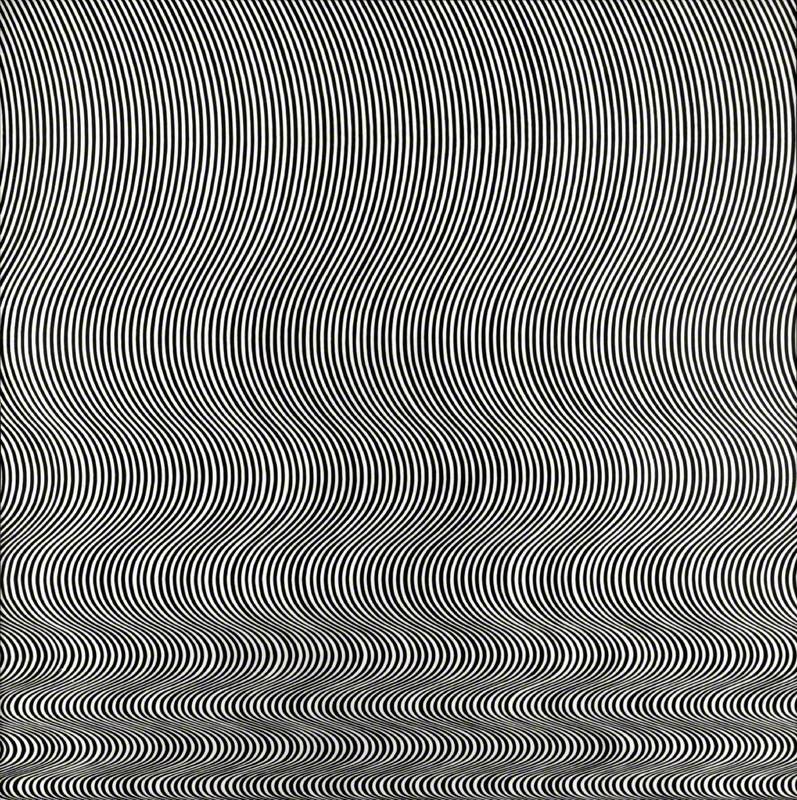

Thirdly, Hoyland's embrace of hybridity is revealed not only to be material, but also cultural. Considering European art, the hybrids' organic shapes playfully recall Joan Miró's elemental forms, contrasting the Abstract Expressionism of Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, giants of the American scene who were early influences on the artist.

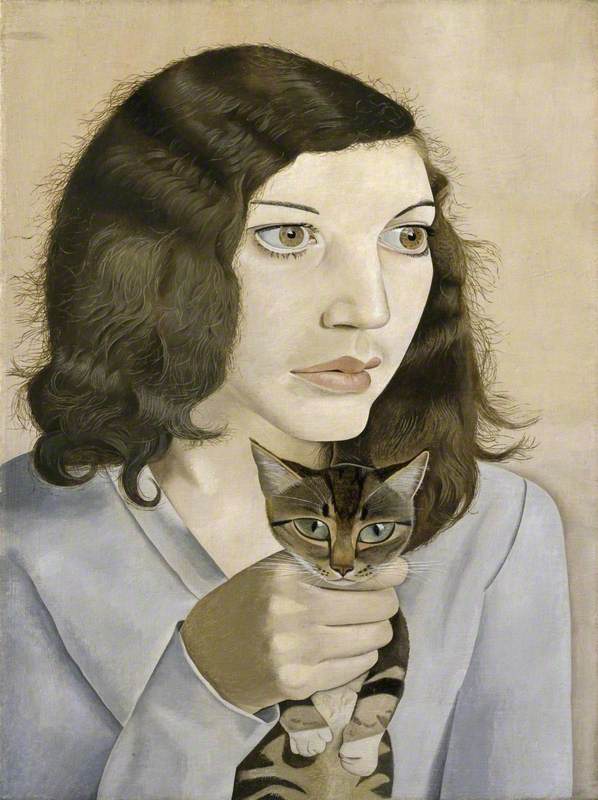

© the artist's estate. Image credit: The John Hoyland Estate

Thupelo Memory

1994, ceramic by John Hoyland (1934–2011)

Seeking inspiration further afield, Hoyland travelled to Johannesburg in 1992 to attend a residency at the Thupelo Workshop which encouraged experimental approaches toward art, partly grounded in the landscape beyond the city. One of the hybrids, Thupelo Memory, featuring red and pink curved tubes and a triangular base adorned with red and blue stripes, was titled after this experience.

Immediately following completion of the hybrids, the artist would travel to Bali, heralding a dramatic departure from his previous abstraction into the ornamental detail of Indonesian culture and its arboreal environments. Although isolated incidents, his sculptures represent the conclusion of the years which preceded them, and this shift in thinking.

Image credit: Sheffield Museums

'These Mad Hybrids' exhibition at the Millennium Gallery

Locating Hoyland's ceramic sculptures in dialogue with other contemporary works that embody a hybrid nature in 'These Mad Hybrids' powerfully demonstrates their importance and enduring legacy. Co-curator Bax's bright yellow How Do You Do (2019), which combines steel, chicken wire, newspaper and other materials to ornithological effect, reflects the hybrids' playful personas.

Andrew Sabin's polyurethane and steel From Time to Time (2018), a surreal dinosaur-like creature dominating the room, affectionately mocks Hoyland's diminutive Dragon. Both Phyllida Barlow's Untitled: Badplace; 2020 Lockdown (2020) and Hew Locke's The Kingdom of the Blind (2008) conjure dreamlike atmospheres charging the gallery with a sense of mystery, mirrored by their hybrid companions.

Image credit: Sheffield Museums

'These Mad Hybrids' exhibition at the Millennium Gallery

'Strange Presence' and 'Imaginary Beings' reassess Hoyland's work on its own terms, while simultaneously acting as conduits linking it to the wider sculptural world. The three exhibitions raise important questions about the nature of sculpture, outlining a compelling case for hybridity, while advocating the 'mad little hybrids' position as having confounded their origins.

Dominic Blake, freelance art writer and theorist

'These Mad Hybrids' and 'Strange Presence' run until 18th May 2025 at the Millenium Gallery, Sheffield

'Imaginary Beings' runs until 16th March 2025 at the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds

Further reading

Olivia Bax and Sam Cornish, These Mad Hybrids: John Hoyland and Contemporary Sculpture, Riding House, 2024