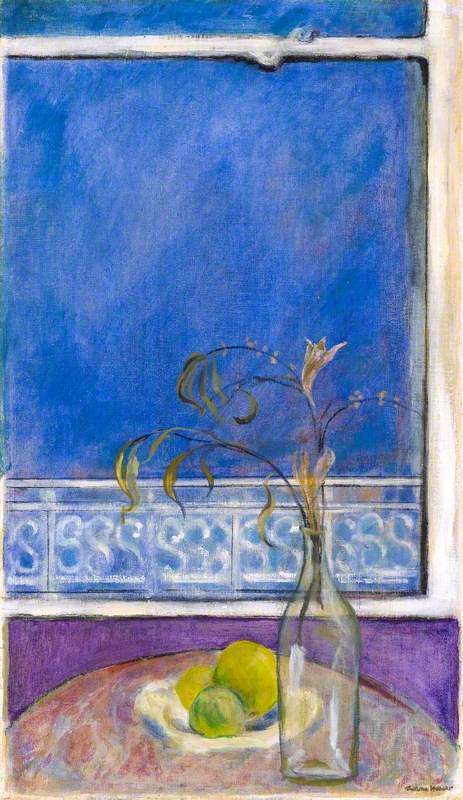

Thelma Hulbert (1913–1995) is one of those artists who has fallen out of fashion. Her painting – still life, often with plants and flowers, and some landscape, in colours that are delicate, with flashes of strength – is not modish, being harmonious and restrained rather than challenging or conceptual.

The danger that Hulbert might disappear from art history was noticed during her lifetime. In a Guardian review of her solo exhibition of 1958 at the Leicester Galleries, the critic Frederick Laws warned against dismissing her: 'Because her themes are apt to be domestic and her colours pale there is a danger that her pictures may be graciously labelled "feminine." They are as ladylike as Bonnard and Turner.'

The poet Frances Cornford, art collector and granddaughter of Charles Darwin, quoted in the catalogue for the same show, described her work as 'almost Proustian in its elaboration of space and light and emotional atmospherics'.

Laws suggested that Hulbert's sex was the problem, and there is something in that – women being more commonly discounted than men in the art world, especially during the years of Hulbert's painting life, the 1930s to the early 1980s. But there is more to it. Although Hulbert allied herself with the celebrated Euston Road School, she never really fitted, her work being – as the critics noted – largely in the tradition of French modernism, with a nod to Turner's evanescent light and luminous colour.

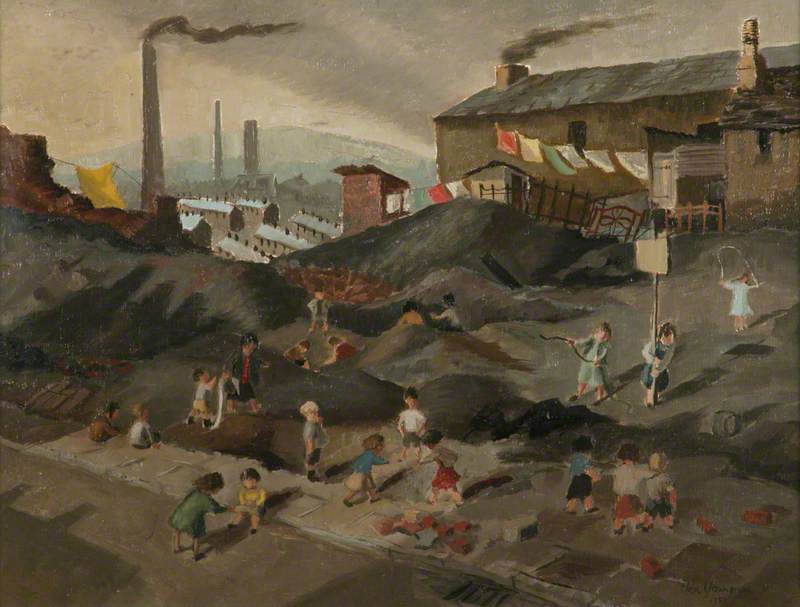

Hulbert, who was from a working-class background (in contrast to many of her female contemporaries), had trained in Bath and at the Central School of Art and Design in London. She launched herself into that city's art world in what the poet W. H. Auden famously described as 'the low dishonest decade' before the Second World War. There was a new austerity in figurative painting afoot, a reflection of the times.

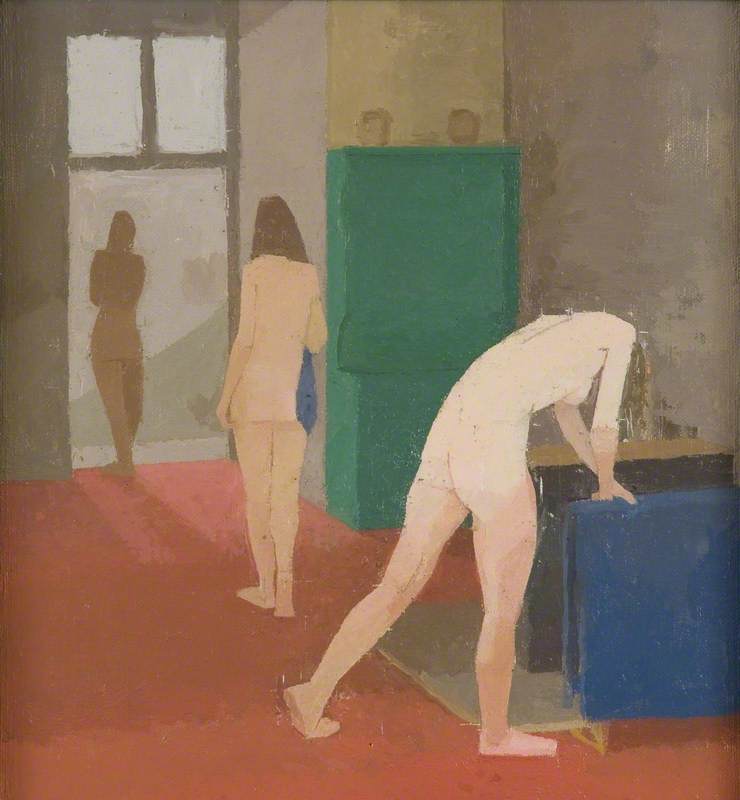

The great depression and the desperate hand-to-mouth existence it meant for many were translated into low tones and downbeat subject matter (brick terraces, bare rooms, impassive sitters in shabby clothes) in the work of William Coldstream, Victor Pasmore and Claude Rogers, who founded and ran the Euston Road School in London between 1937 and 1939.

Hulbert joined the school as organising secretary (women artists often took this kind of support role in the art world at this time) but her work was always different.

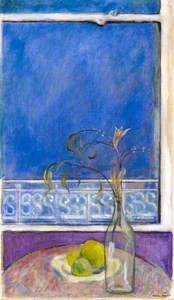

© the copyright holder. Image credit: Royal Albert Memorial Museum & Art Gallery

Dressing Table and Flowers 1939

Thelma Hulbert (1913–1995)

Royal Albert Memorial Museum & Art GalleryThere was an atmosphere of macho dourness about Euston Road, a conviction that lightening the tone and widening the range of the palette meant a lack of seriousness, a distasteful, feminine frivolity, that Hulbert never shared.

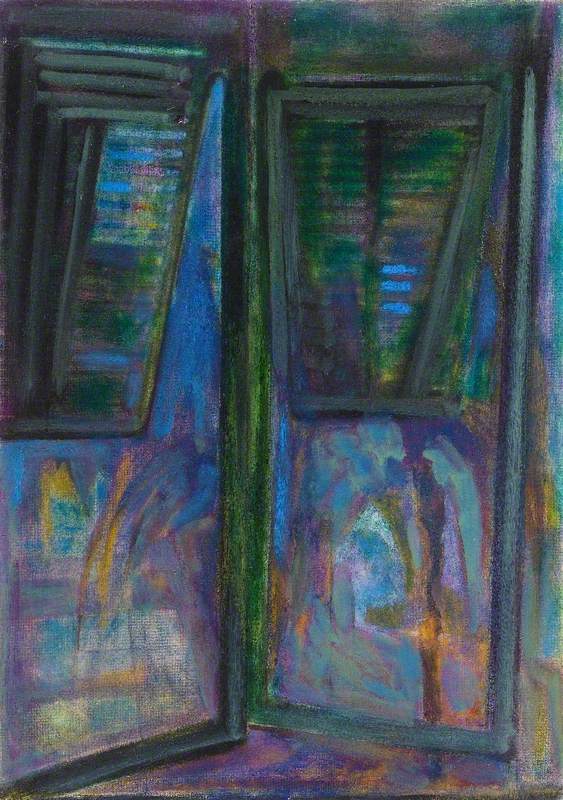

Hers was a more poetic approach that allowed glimpses of light and beauty (literally and metaphorically), often using the motif of transparent fabrics hanging by windows, hence, perhaps, Frances Cornford's admiration. Cornford had been a purchaser of Gwen John's work, an artist from an earlier generation who found poetic resonance in curtained, sunlit windows.

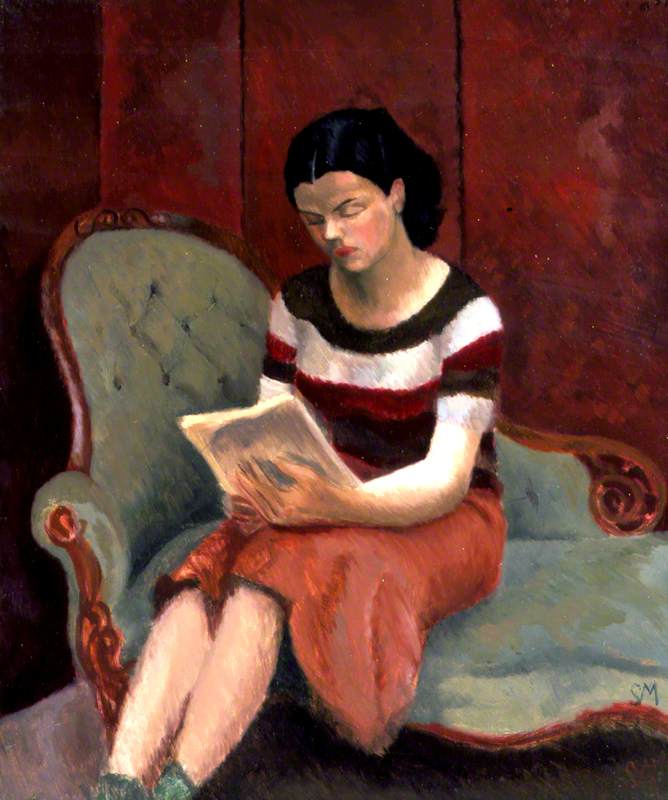

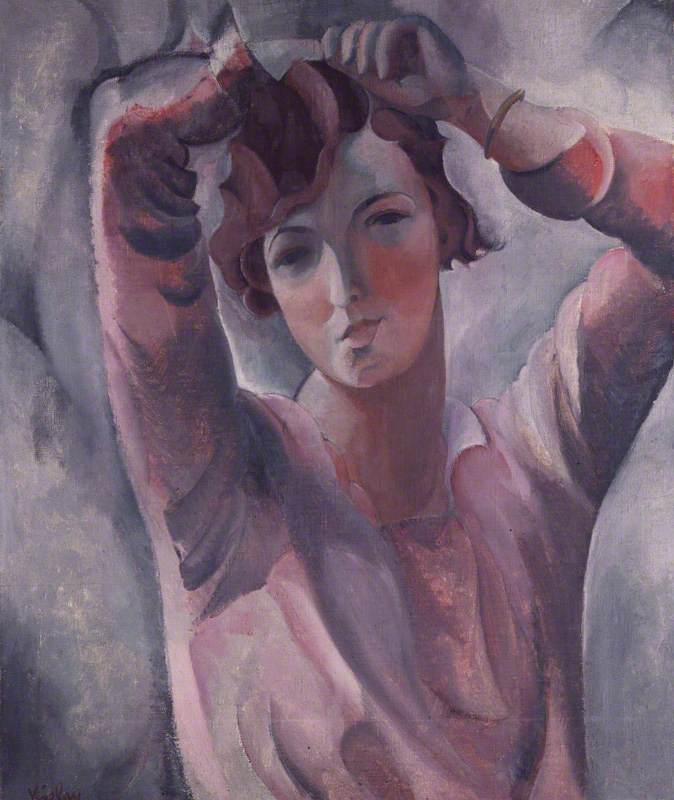

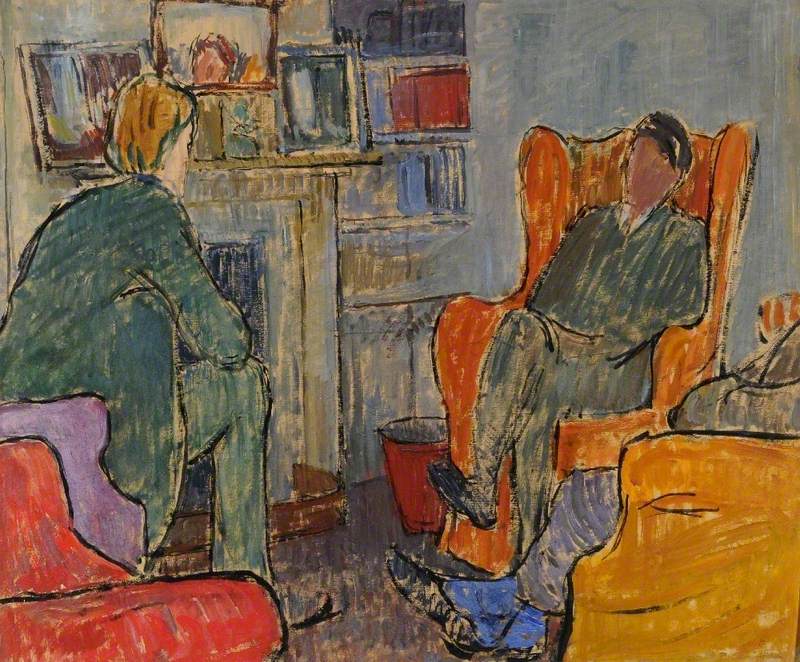

Being drawn to, but also at odds with, the Euston Road School meant that Hulbert was more in sympathy with a student there: Sylvia Melland. Melland was seven years older than Hulbert, a figurative painter like her and, also, as Hulbert was, influenced by French modernism. In Melland's case, this was a predilection for the brilliant colours of Van Gogh and the sinuous lines and compositional inventiveness of Matisse.

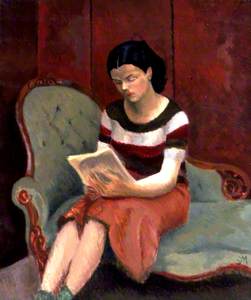

Their shared artistic roots in French painting brought the pair together in a close friendship and they held a joint exhibition at Basil Jonzen's Weekend Gallery in 1948. Melland's portrait of Hulbert from around this time is vivid and direct.

Though she sits on an antique chaise longue she is a picture of modern youth in her striped t-shirt, bright skirt and short socks. Hulbert enjoyed experimenting with her appearance and was known for wandering the artists' locale of Fitzrovia dressed in Edwardian clothes she found second hand on the Caledonian Street market.

The outbreak of war put an end to the Euston Road School and Hulbert worked for a time in a canteen for refugees in Gibraltar. As a young woman she had paid her way by painting flowers on china in a sweatshop and teaching ballroom dancing, and when she returned to London after the war she earned her living teaching, at Camden High School for Girls (which owns one of her paintings) and then at the Central School of Art and Design where she had trained herself.

She continued to exhibit – before the war, she had shown with the London Group – and in 1962 she was given the accolade of a solo show at the Whitechapel Art Gallery. A number of abstract landscapes from the 1960s mark a departure from her flower works in her depiction of rocks and choppy seas.

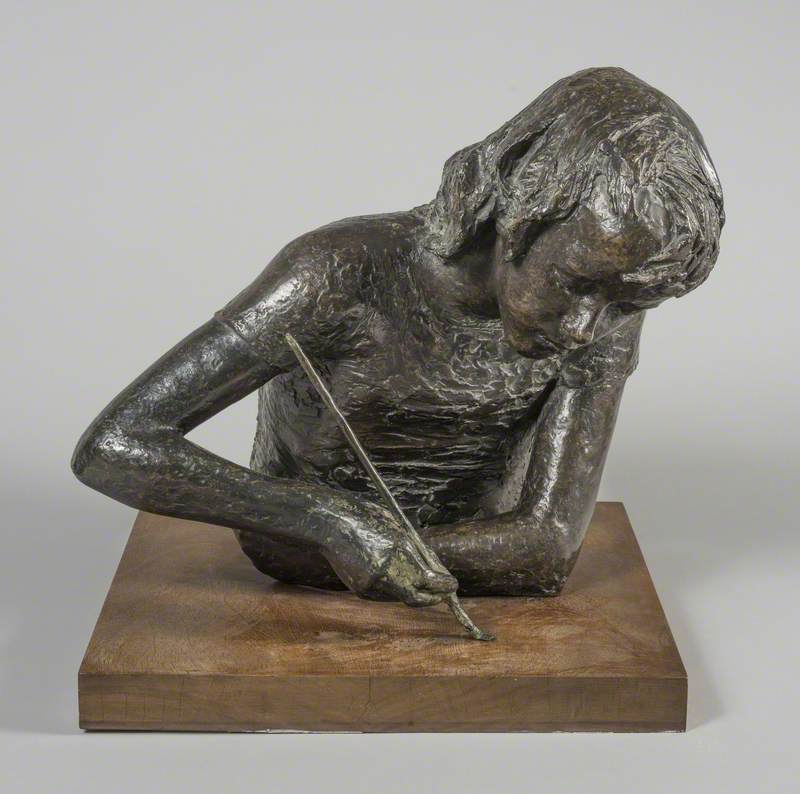

Hulbert shared her commitment to education with her women artist friends, all of whom also worked as teachers: Elsie Few (wife of Claude Rogers), Nan Youngman (who was the originator of the 'Pictures for Schools' exhibition in 1947) and Youngman's partner, the sculptor Betty Rea.

This was not only a way of surviving financially – women being less likely to earn their living from their art alone – but also prompted by their mutual desire to democratise art. Rea's tender but clear-eyed bust of a young girl intent over her sketchbook is a moving and necessary reminder of the often-overlooked role these women had in bringing art to the generations that followed them.

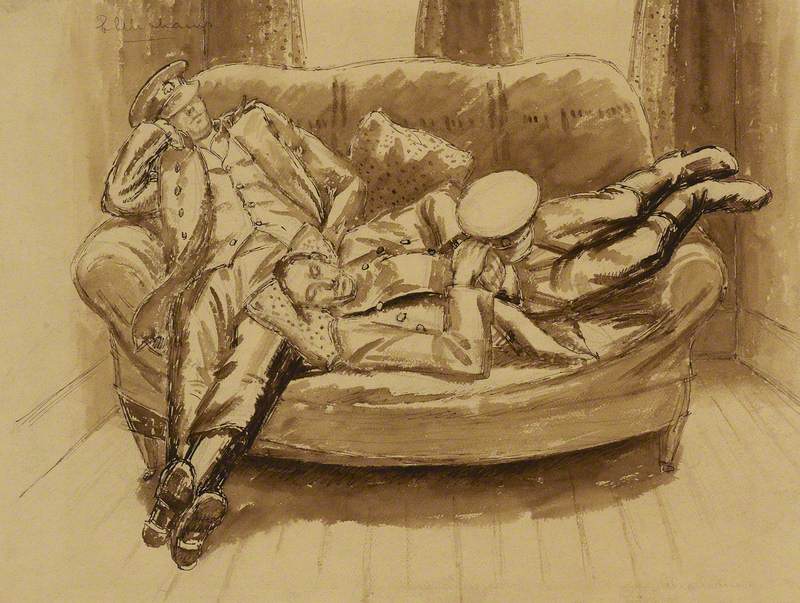

Elsie Few's record of her friendship with Hulbert, a portrait of her painting at the Euston Road School, is now sadly lost. It was shown at the major 1948 exhibition of Euston Road artists and students held at the Wakefield City Art Gallery. But when, in the same year, the Arts Council mounted a concentrated version of the show in London, Few's portrait, along with every other work by a woman artist, had been edited out.

In 1984 Hulbert retired and left London for Honiton, Devon, where she spent her final decade. Her home there, Elmfield House, is now that very rare thing, a museum devoted to a woman's work. The Thelma Hulbert Gallery, which reopens in March 2025 following refurbishment, preserves her art and shows it alongside contemporary exhibitions.

Alicia Foster, writer and curator

For more information, visit www.thelmahulbert.com

This content was supported by Jerwood Foundation