The splendid portrait of master printer and 'father of the English novel' Samuel Richardson (1689–1761) is one of the treasures of The Stationers' Company collection. It was painted by Richardson's friend and direct contemporary Joseph Highmore (1692–1780). Both men's careers touched at several points over the years.

Richardson, one of our most famous Stationers, was a Derbyshire lad. He was bound apprentice to a London printer, John Wilde, at an early age. Consolidating commercial and family ties through marriage first to the daughter of his master and then, after her death, to the sister of a successful bookseller in Bath, Richardson first acquired and then successfully grew his printing business to become an important figure in the London publishing and bookselling worlds.

He played an active part in our Company for nearly 50 years, becoming a Freeman in 1715, a Liveryman in 1722, and ultimately Master towards the end of his working life.

In 1740, at the age of 50, Richardson wrote the first of three novels on which his fame depends. This was Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded. Richardson was encouraged in this venture by his friend and fellow Derbyshireman Charles Rivington, founder of the Rivington publishing house and forebear to a family who would go on to contribute no fewer than twelve Masters to The Stationers' Company. Rivington had discovered Richardson as a 13-year-old apprentice composing ardent love letters for fellow apprentices less gifted with words than himself.

Told in the form of letters, Richardson's Pamela – often listed among candidates for 'the first English novel' – concerns a virtuous lady's maid whose heartfelt missives home reveal her daily battles against an aristocratic employer's relentless attempts at seduction. Pamela's steadfast virtue is rewarded: she reforms her employer and ultimately receives his hand in marriage. The novel aroused strong feelings both for and against its heroine, and the book became an instant best-seller.

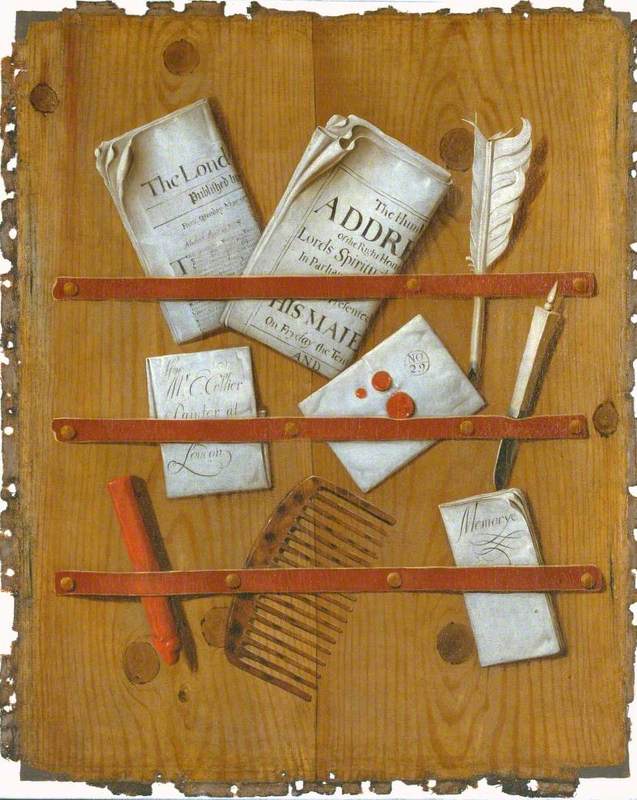

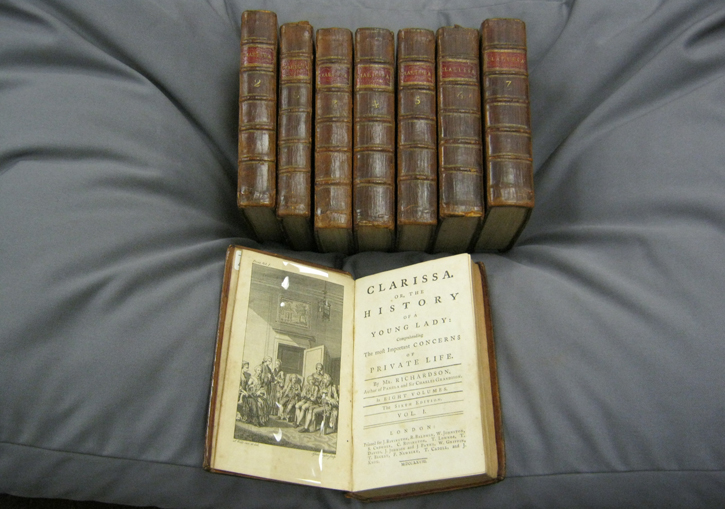

Samuel Richardson's books

Richardson, now a substantial figure in literary London and an associate of Dr Johnson, William Hogarth, David Garrick and other luminaries of the day, repeated this triumph eight years later with a second and rather more sombre novel, Clarissa; or, The History of a Young Lady. And his final novel, Sir Charles Grandison, in which the eponymous male character echoes the virtuous qualities of Pamela and Clarissa, completed a trio of literary sensations. Taken together these high moral tales of social manners ensured the widescale reach and success of the 'sentimental novel', creating a literary genre that remained in vogue for many decades thereafter.

Our artist Joseph Highmore benefited no less from the success of Richardson's works. Already a prolific and versatile producer of portraits, history paintings and literary illustrations for a predominantly middle-class audience, Highmore made a series of twelve paintings in the years following the publication of Pamela. These works depicted morally uplifting scenes from the story, in that rather stiff and doll-like idiom of many 'conversation pieces' of the period. Here is Pamela herself, now happily married, instructing her children on how they should behave.

In short order, Highmore had the series engraved and published as prints, the standard route at this time to widen one's audience and extend income. But as a well-established artist, Highmore was also more than ready to give back: like his London contemporaries Handel and Hogarth, he was in that circle which supported Thomas Coram's Foundling Hospital through its early years, donating a painting of Hagar and Ishmael which remains part of their collection to this day.

Highmore maintained a successful portraiture business to the end of his working life, and although he never attained the same status as the later generation of more famous eighteenth-century portrait painters such as Gainsborough or Reynolds, his work was sought after and widely appreciated in its day.

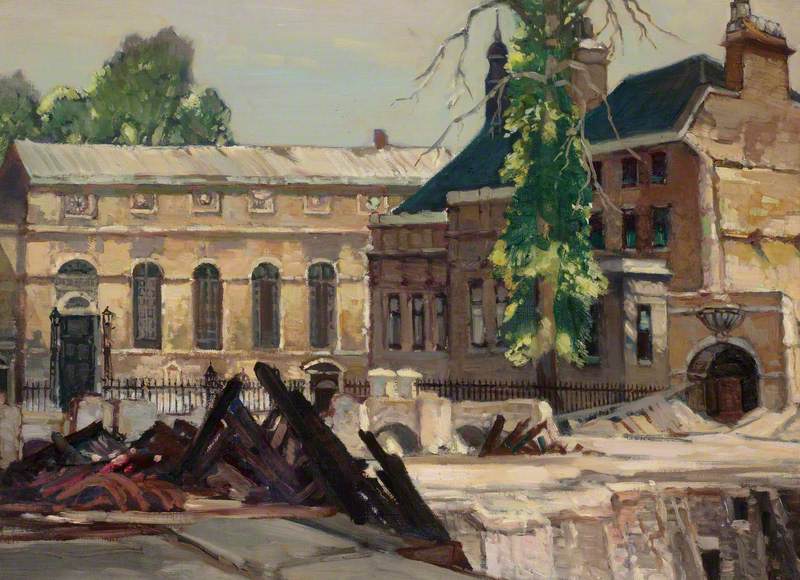

Our forceful portrait of Samuel Richardson is not the only Highmore The Stationers' Company has possessed. The artist painted a pendant picture of Richardson's second wife, née Elizabeth Leake, which hung alongside that of Samuel in the Hall until it was destroyed in a bombing raid at the end of 1940. (Now it is known to us only through black-and-white photographs.) Highmore painted Mrs Richardson sitting on an elaborate rococo garden chair, with a landscape scene opening up behind her. It would have made an excellent complement to Samuel.

The Stationers' Hall after Enemy Action in 1940

Leonard Richmond (1889–1965)

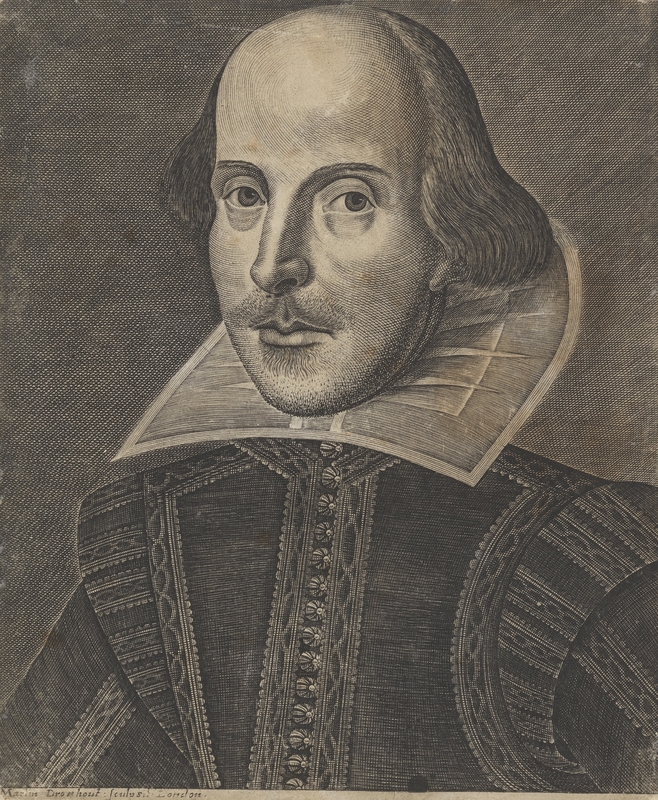

Alongside the Richardson portraits, The Stationers' Company has accumulated a fascinating range of pictures, collected over several centuries. The majority are portraits, with the eighteenth century being particularly well represented in works by Godfrey Kneller, Nathaniel Dance-Holland and William Beechey amongst others. Famous Stationers of the century who peer down from the walls of the Hall include Thomas Guy, founder of Guy's Hospital, and the indefatigable print-publisher John Boydell of 'Shakespeare Gallery' fame.

Prominent amongst Stationers of the following century come Luke Hansard, founder of those transcripts of MPs' debates which still bear his name, and Sir Sydney Hedley Waterlow, printer, politician, philanthropist, Lord Mayor of London, and donor to the public of lovely Waterlow Park in Highgate.

Bringing the parade of Stationers' portraits closer to present times are: an excellent mid-twentieth-century portrait by Cosmo Clark of John Mylne Rivington, Master in a long line of Rivington family members who have given such invaluable service to the Company over 250 years; a competition-winning portrait of Harold Macmillan Lord Stockton, painted by talented Sri Lankan artist and photographer Gandee Vasan; and a fine portrait of Fleet Street colossus Sir Edward Pickering by the celebrated portraitist Henry Mee, painted at the turn of the millennium.

John Peacock and Margaret Willes, Liverymen at The Stationers' Company