Writing in the 1960s, the Welsh painter Ceri Richards (1903–1971) observed that 'the relation between music and painting is a vast field of thought'.

'There is certainly a deep link… the proportions of time, the geometry of rhythms and division of spaces. This is also true of poetry and architecture. The sensuous entity that a piece of music or painting becomes ensues from the special adjustments of these elements.'

In a remarkably stylistically varied body of work, music and poetry were constant threads in Richards' output. He explored these themes throughout his career in increasingly original and profound ways, evolving them into broader metaphors for art and life, and what it is to be human.

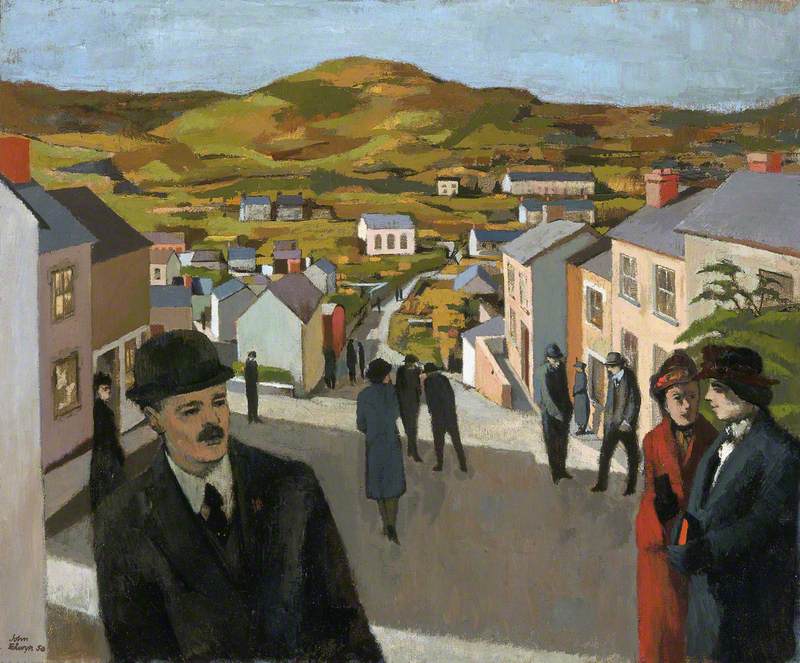

Richards was born in Dunvant, Swansea, on the edge of the Gower peninsula, where his father, a tinplate worker, was a choir conductor and poet. It was a culturally rich environment, and Richards and his siblings were encouraged to read and play music. These early influences, and the coastal landscape with its rhythms of nature, became central to his creative imagination.

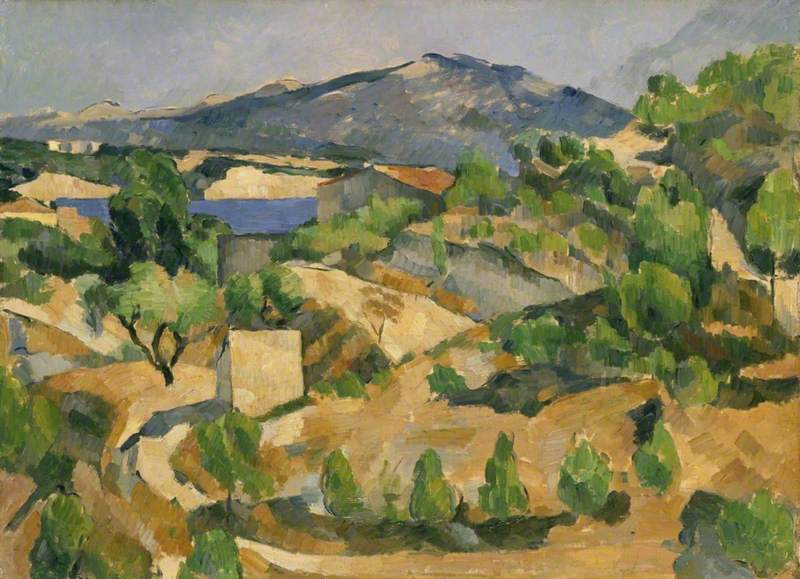

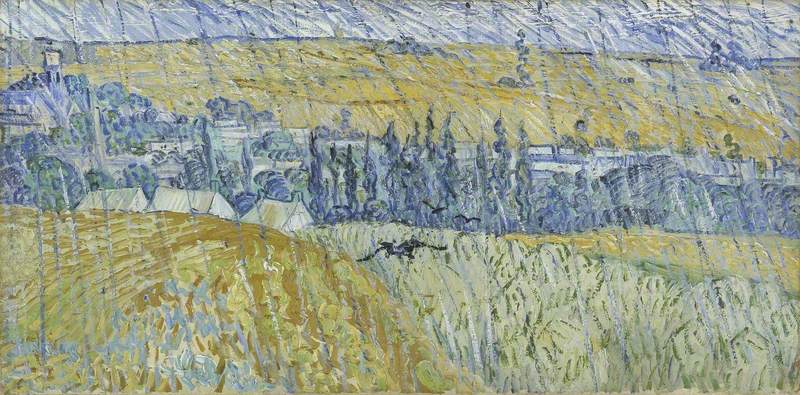

While at Swansea School of Art in 1923, he attended a summer school at Gregynog Hall in mid-Wales, home of pioneering collectors Gwendoline and Margaret Davies. It was here that he had his first encounter with work by artists such as Van Gogh, Cézanne and most importantly Monet, of whom Richards wrote: 'Imagine their effect on someone who'd dreamed of great painting but seen none at all.'

In the evenings, students would gather in the music room at Gregynog, where the walls hung with Impressionist and Post-Impressionist work from the sisters' collection. They would perform together, Richards himself often playing the piano. This experience at Gregynog was transformational, encouraging him to apply for a scholarship to the Royal College of Art, where he began his studies in 1924.

In London, the world opened up further still. Richards became increasingly interested in European modernism, with Picasso and Matisse becoming immediate and lifelong influences.

He absorbed Wassily Kandinsky's text Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1912), which espoused the interconnectedness of music and painting, and the emotional possibilities of the abstract qualities of colour and sound.

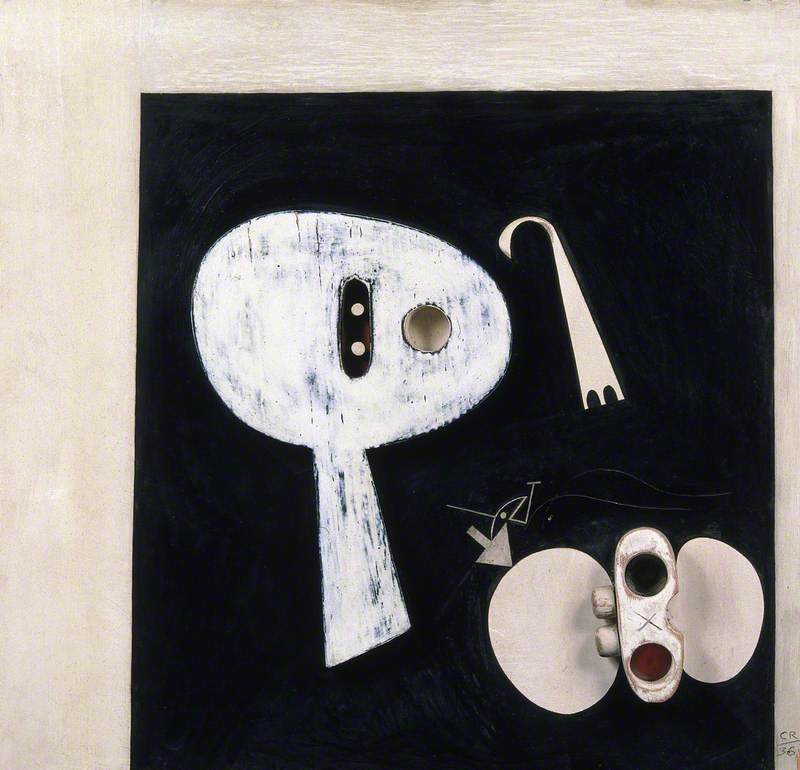

The language of Surrealism, particularly the work of Max Ernst, gave Richards the tools to explore the far reaches of his imagination. Although he was never an official member of the movement, the lessons he learnt from the Surrealists – that the metaphysical, the poetic, the symbolic were a valid means of interpreting things observed – came to underpin his work. Surrealism, he said, 'helped me to be aware of the mystery, even the unreality of ordinary things.'

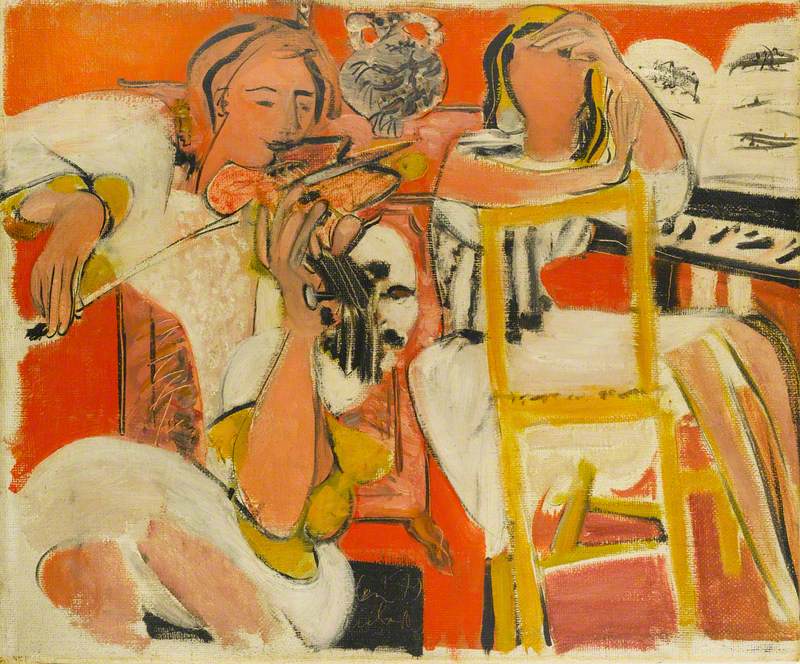

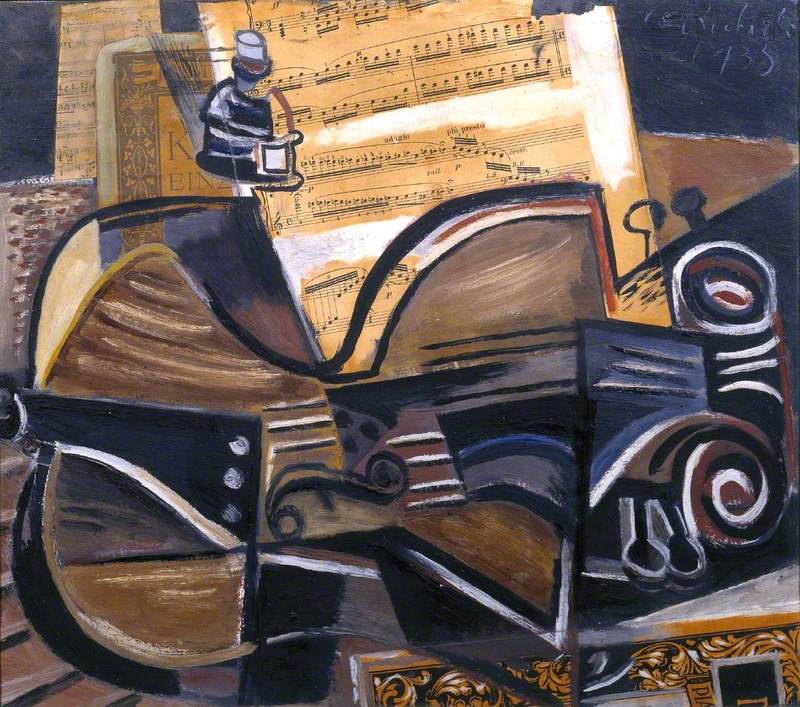

The idea of music took many forms across Richards' art. He was inspired by the act of music-making, the language and colour of sound, by certain composers, by particular pieces. His works are invariably dynamic, rhythmical, sonorous. Even those not specifically 'about' music, such as the 'Trafalgar Square' series, for example, or images of East End costermongers, are alive with sound – of voices, church bells, of birds and barrel organs.

Richards was an accomplished pianist and played every day. It was only natural that the piano itself would become a recurring presence in his work; in an early painting of his wife, the artist Frances Clayton, it plays a discreet but vital formal role at the left edge of the canvas.

In the 1930s Richards began a series of Surrealist-inspired constructions, including, in 1934, Piano. This established the foreshortened keyboard motif which would become familiar in subsequent work, as well as the often-present figure of the pianist.

The two forms in this work – player and decidedly anthropomorphic piano – also speak to Richards' exploration of psychoanalytic concepts of desire and dynamic opposition explored in constructions such as White and Dark and Sculptor and Model.

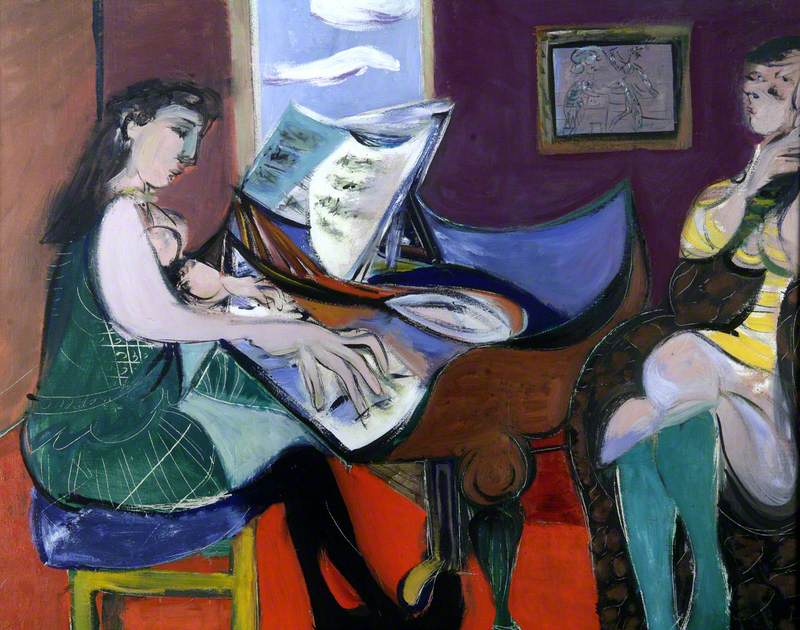

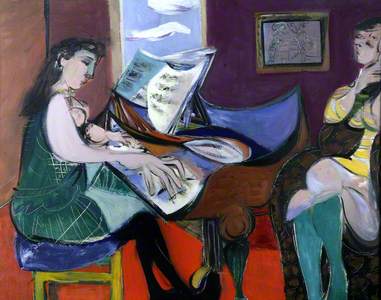

Inspired by Matisse's treatment of the subject, Richards went on to develop the theme of the music room – a series of interiors with women at the piano.

The format allowed Richards to experiment with perspective, form, pattern and mood. Ranging from figurative to semi-abstract, these interiors are richly coloured, the walls often decorated with Richards' own paintings derived from Old Master subjects. They are closed environments of beauty and harmony, in which art and life – past and present – converge.

To this he added nature, introducing the device of an open window into the music room, through which bright sunlight would saturate the space in a dazzle of life-affirming energy. This additional sensory element combined ideas which had become central to his work by this point: the power of nature, music and art.

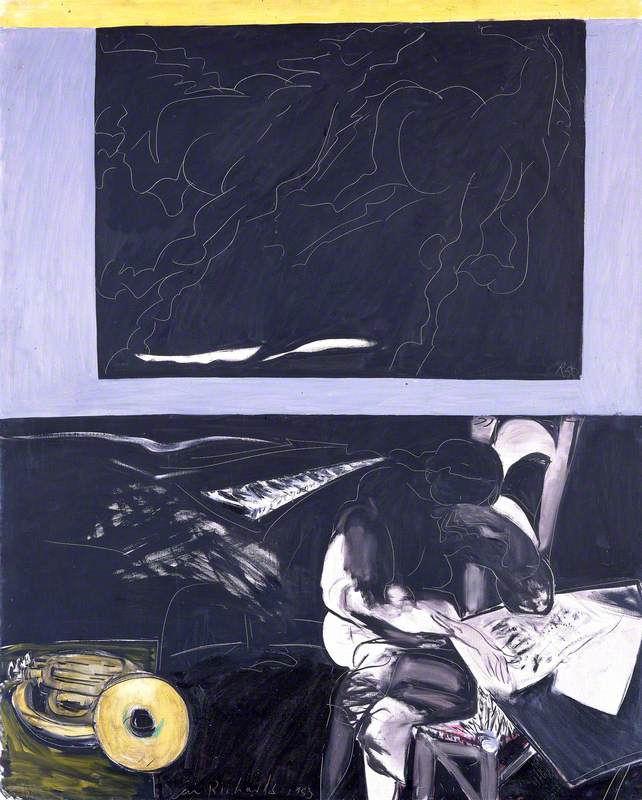

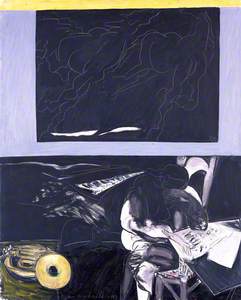

From the late 1940s, Richards took an increasingly symbolic approach to both the music room and the theme of music more generally. A painting of 1949 introduced the figure of Saint Cecilia, patron saint of music and musicians. In this image, she merges with the piano, the player and instrument becoming one.

Saint Cecilia appears again in his series of homages to Beethoven, a figure of huge significance for Richards. In a number of these works he splits the canvas into defined zones (a format taken directly from Matisse), the black panels with mute piano a reflection on life, death and the enduring creative legacy. The composer himself is signified only by the sheet music over which the sgraffito form of Saint Cecilia bends in contemplation.

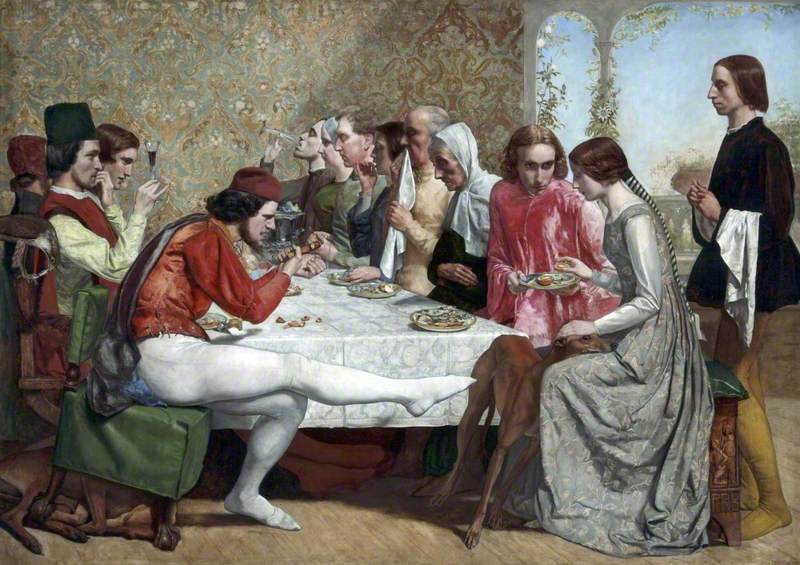

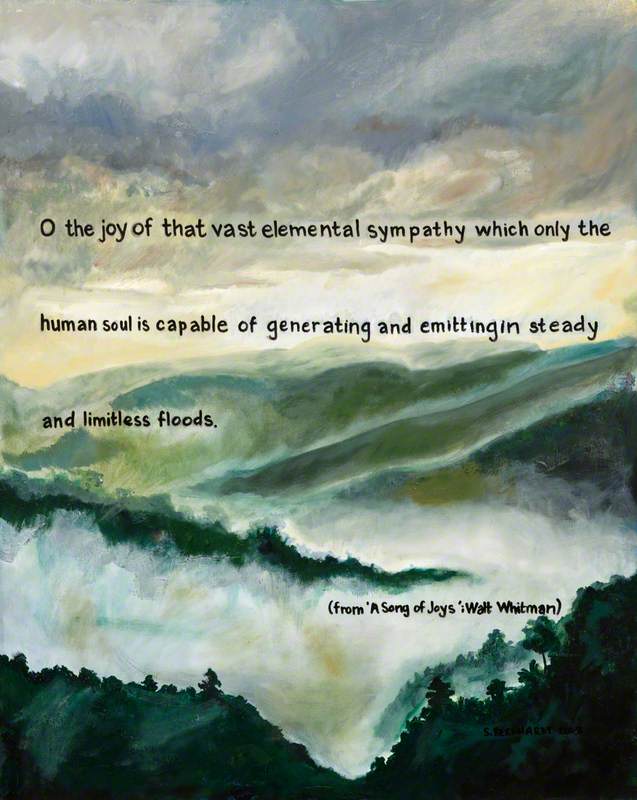

Richards viewed poetry in similar terms to music in relation to the possibilities it opened up for painting. It had been a direct catalyst for early work, such as The Female Contains All Qualities, a Surrealist-style 'chance' image derived from Walt Whitman's nineteenth-century poetry collection Leaves of Grass.

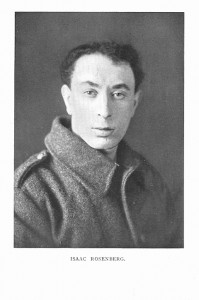

But as an exploration of text and image, it was the writing of Welsh poet Dylan Thomas (1914–1953) with which Richards developed a deep and lasting connection.

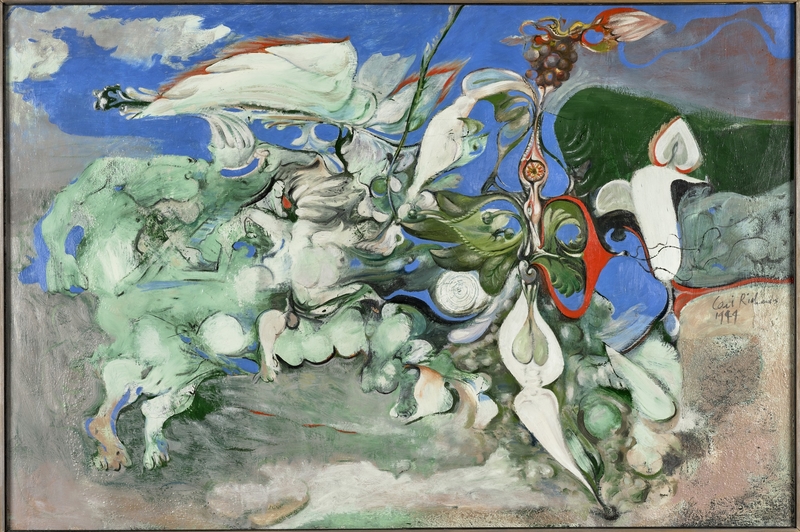

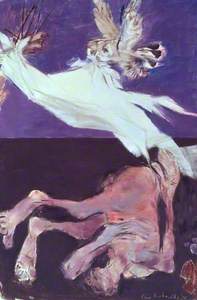

Thomas' lyricism, allusion and vivid imagery were the perfect fit for Richards' romantic vision. In 1943 he was commissioned to illustrate the poet's work for Poetry London. Of these, Summer, the Force that through the Green Fuse Drives the Flower, with its themes of the life-cycle, of nature, sex, death and renewal, would become a rich seam of inspiration, producing ideas and motifs which Richards would draw on throughout his life.

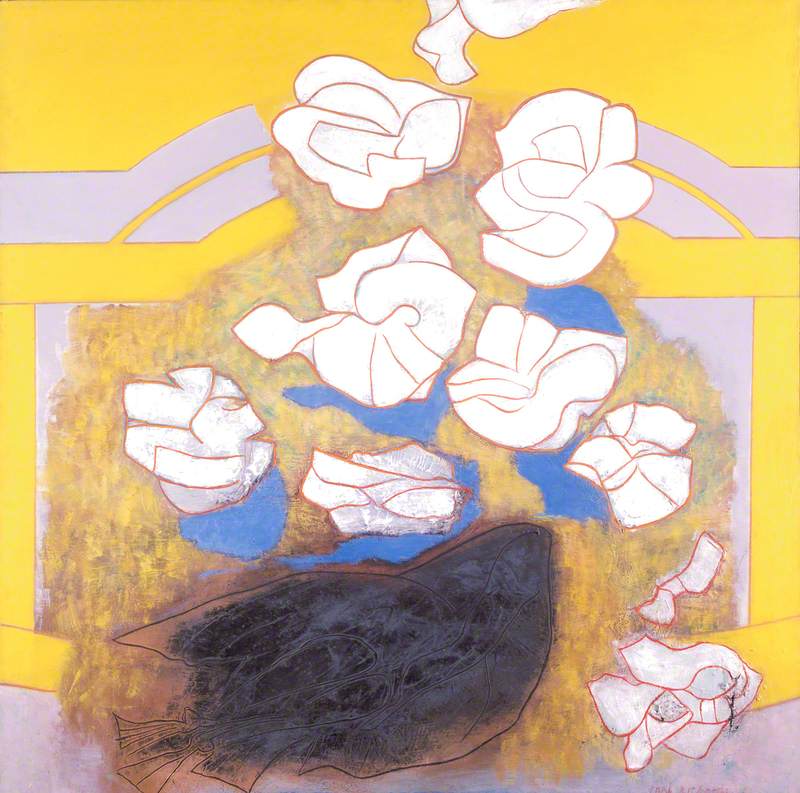

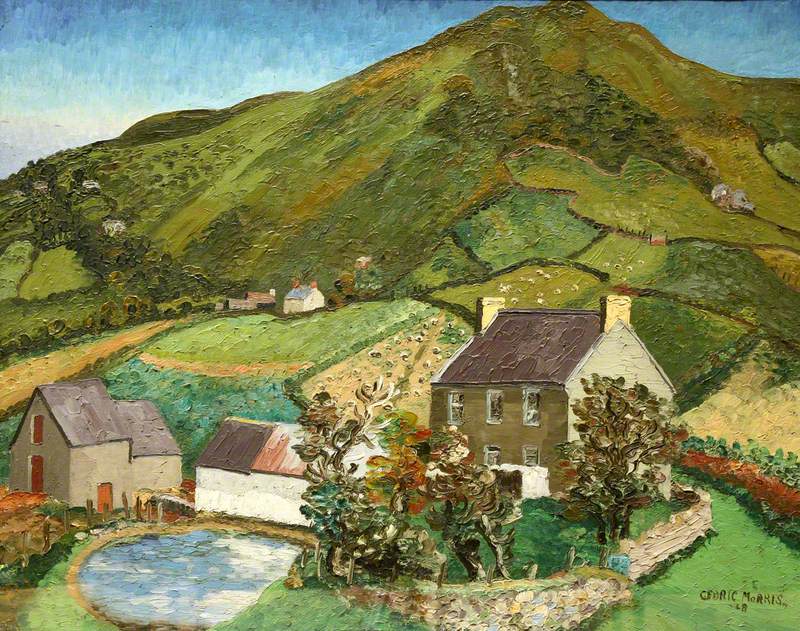

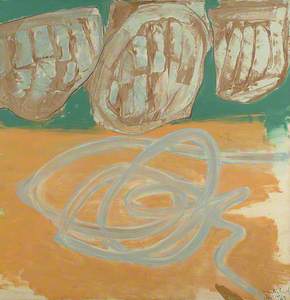

Summer, the Force that through the Green Fuse Drives the Flower

1968

Ceri Giraldus Richards (1903–1971)

As well as the illustrations, the poem was the catalyst for major related oils such as Cycle of Nature (1944), a writhing cacophony at once human, animal, plant; a rhythmic tangle symbolising procreation and nature. Richards would return regularly to ideas and motifs explored here, as seen in the 1964 work Cycle of Nature, Arabesque I.

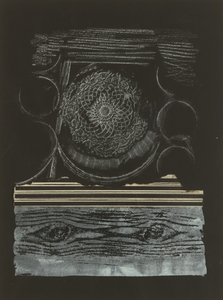

It also led to 'Afal du Brogŵyr (Black Apple of Gower)', an enigmatic series of works locating the theme directly within the landscape of his childhood, which introduced the motif of the circular mandala form which would become a recurring presence throughout the 1950s and 1960s, particularly in the 'La Cathédrale engloutie' series.

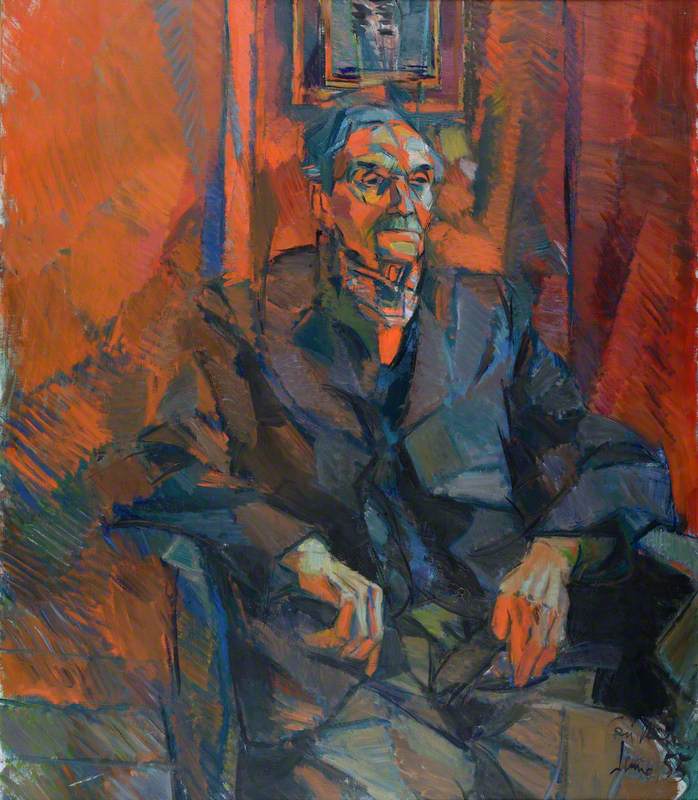

Despite the obvious synergy between Richards and Thomas' work, the pair in fact met only once, in Laugharne, shortly before Thomas' death in 1953. Richards was profoundly moved by the unexpected loss, and lamented the opportunity to form a relationship with the poet.

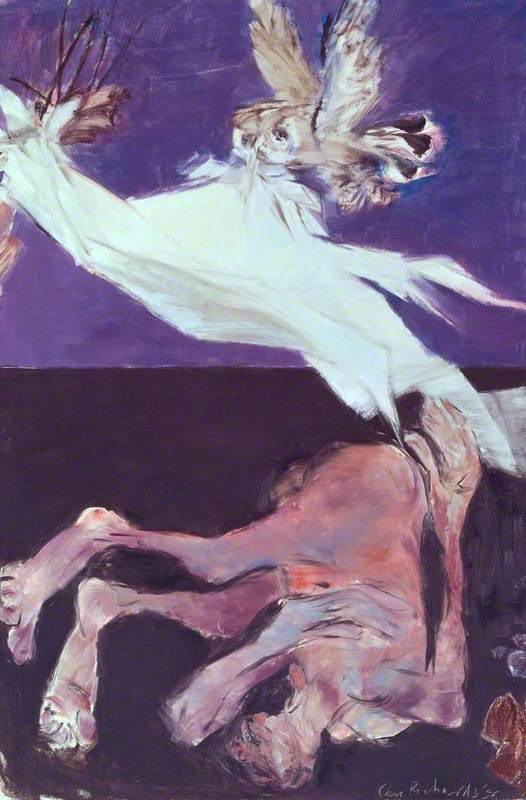

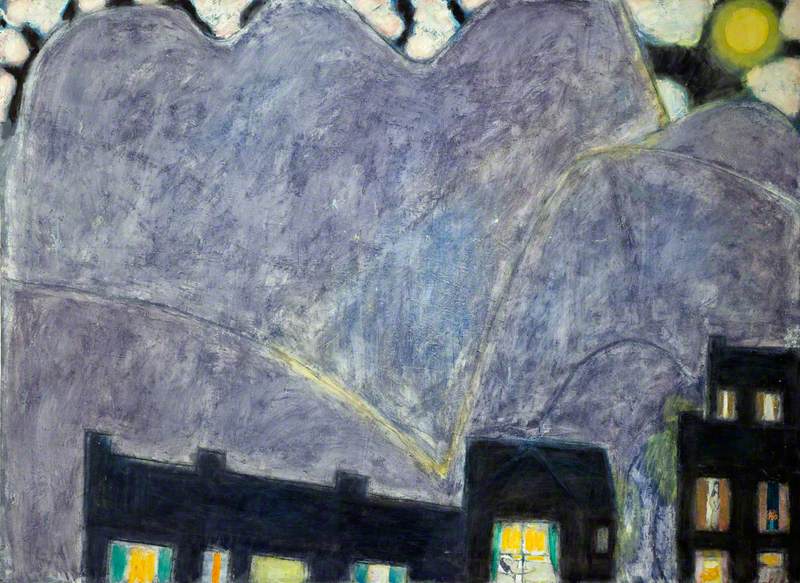

In the years after, a series of works based on Thomas' Do not go gentle into that good night emerged. Here, as in the Beethoven homages, Richards symbolises mortality via the division of the canvas into two distinct parts, one a dense black into which '...the figure falls from the shroud into the deep unknown.'

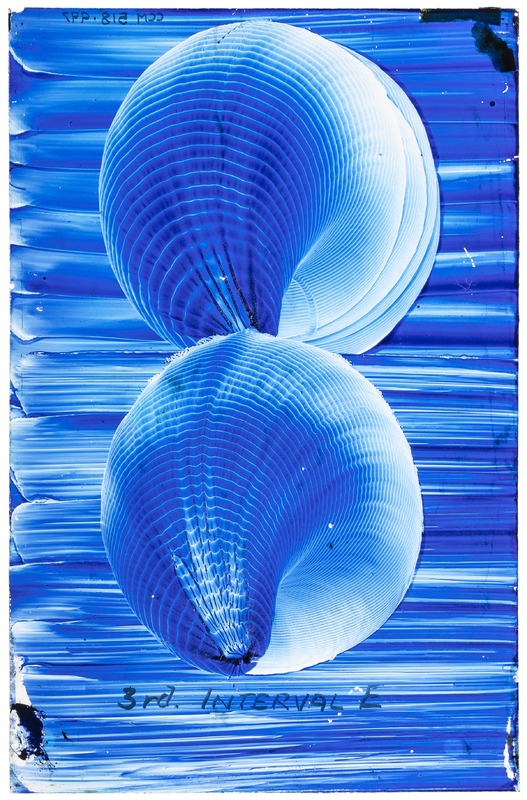

In 1957, Richards began his most sustained and creative engagement with a single piece of music – French composer Claude Debussy's piano prelude La Cathédrale engloutie.

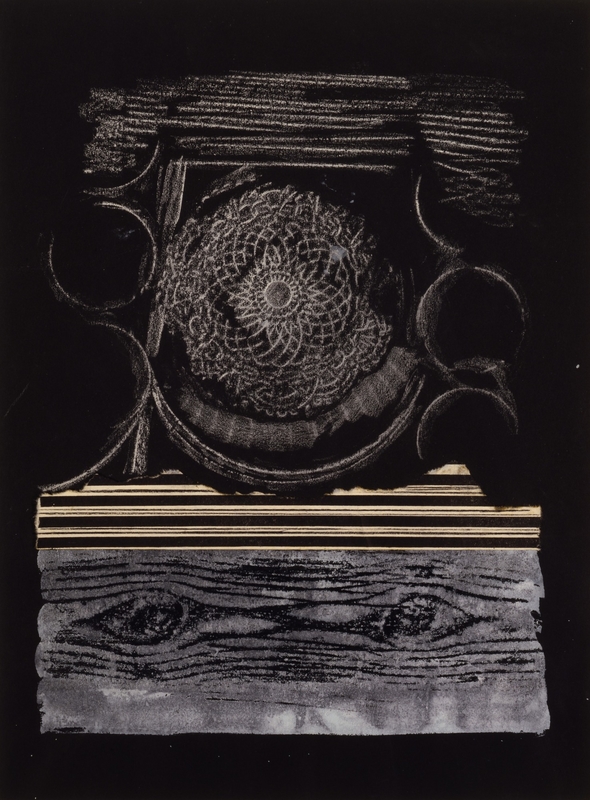

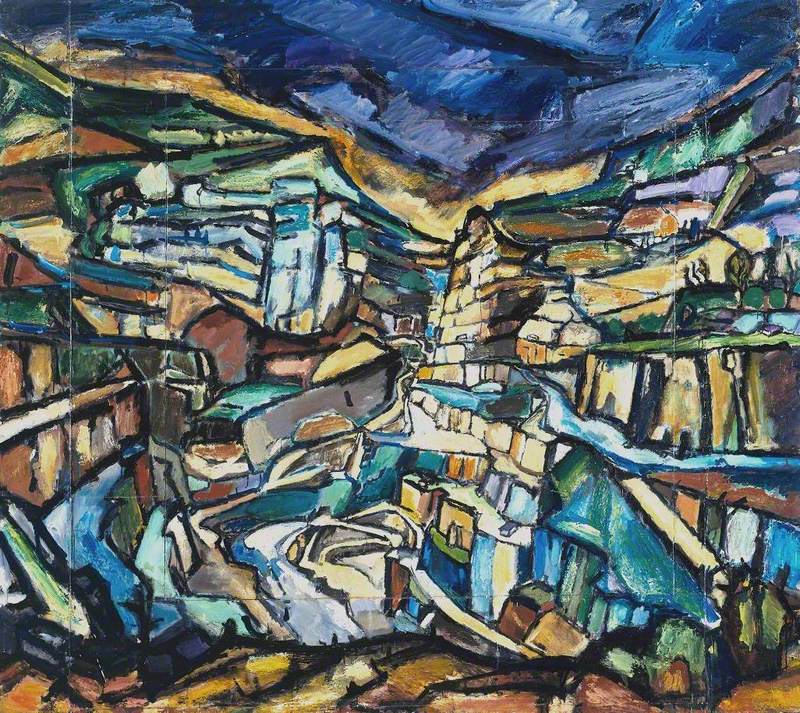

La Cathédrale engloutie: Augmentez progressivement

c.1960

Ceri Giraldus Richards (1903–1971)

Debussy's work responds to the legend of the submerged cathedral of Ys off the coast of Brittany, which on calm, clear days is said to rise from the water in a peal of bells. Richards described Debussy as a 'visual composer', writing that 'he gives me a feeling of the sounds of nature, as Monet does.'

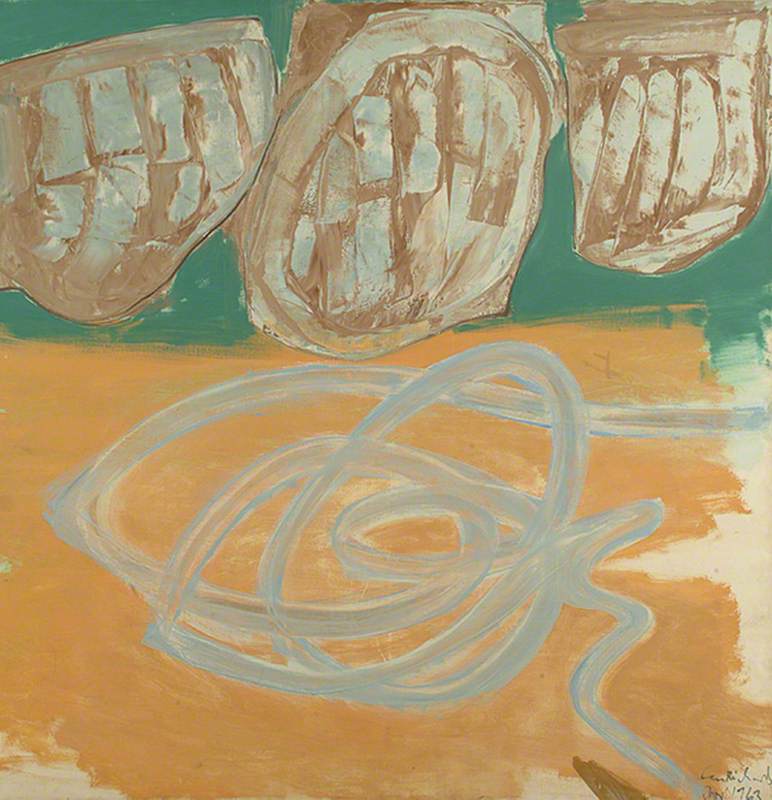

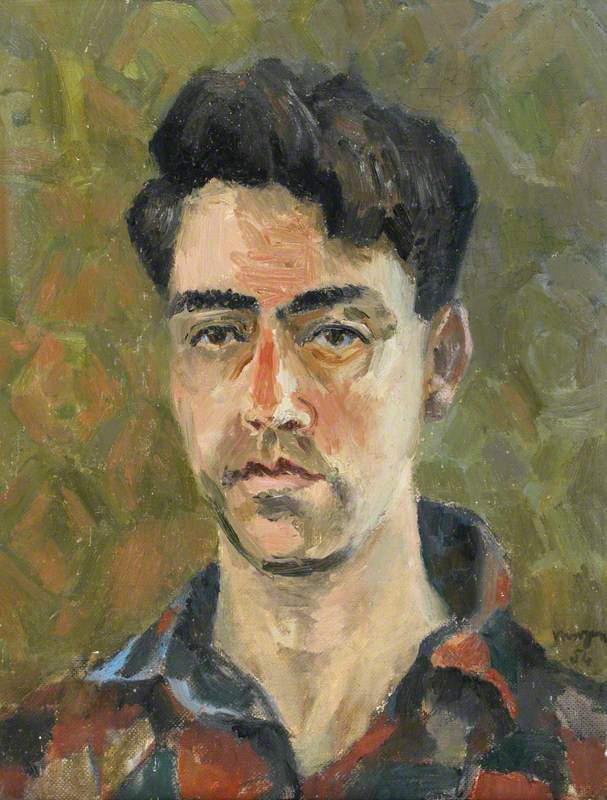

La cathédrale engloutie, profondement calme

1962

Ceri Giraldus Richards (1903–1971)

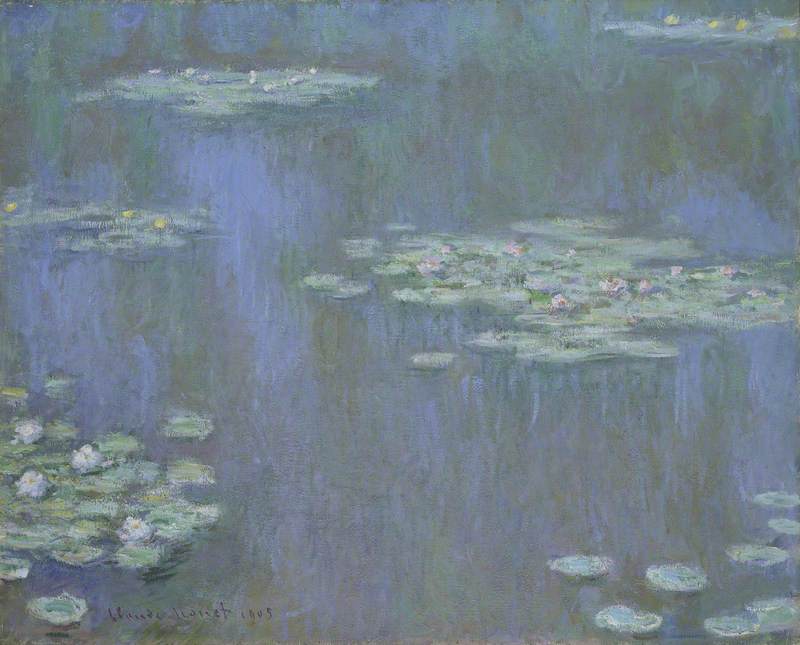

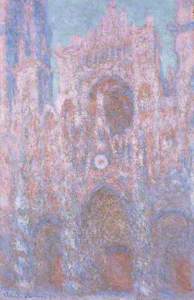

Richards claimed the landscape of Gower as the inspiration, but other synergies would also likely have fed his imagination. For example, it was the year in which the Tate Gallery mounted a show of work by Monet, where Richards would certainly have reconnected with the Davies sisters' image of Rouen Cathedral first seen at Gregynog Hall, its barnacle-like impasto rendering the form of the cathedral at sunset.

Rouen Cathedral: Setting Sun (Symphony in Pink and Grey)

1892–1894

Claude Monet (1840–1926)

While the legend of Ys is strikingly visual, it was the shape and sound of La Cathédrale engloutie which Richards responded to. As Debussy uses the extremities of the piano keyboard to describe space and depth, light and dark, so Richards does in his textural palette of rich, plangent blues and morning yellows.

The series brings together once more the themes of art, nature and renewal: the cathedral architecture morphs into the geology of the coastal landscape, the recurring roundel form is both the stained-glass rose window and the 'black apple of Gower', which Richards described as 'the metaphor expressing the sombre germinating force of nature… seated within earth and sea.'

Richards returned to Debussy in a series of further works including Poissons d'or, in which the trajectory of darting goldfish ribbons across the canvas, Ce qu'a vu le vent d'Ouest, and Clair de Lune, variations on the moon's reflection on the canals and bridges of Venice, where Richards represented Britain at the Biennale of 1962. In all of these, as critic Mel Gooding has observed, the movement of natural phenomena is central.

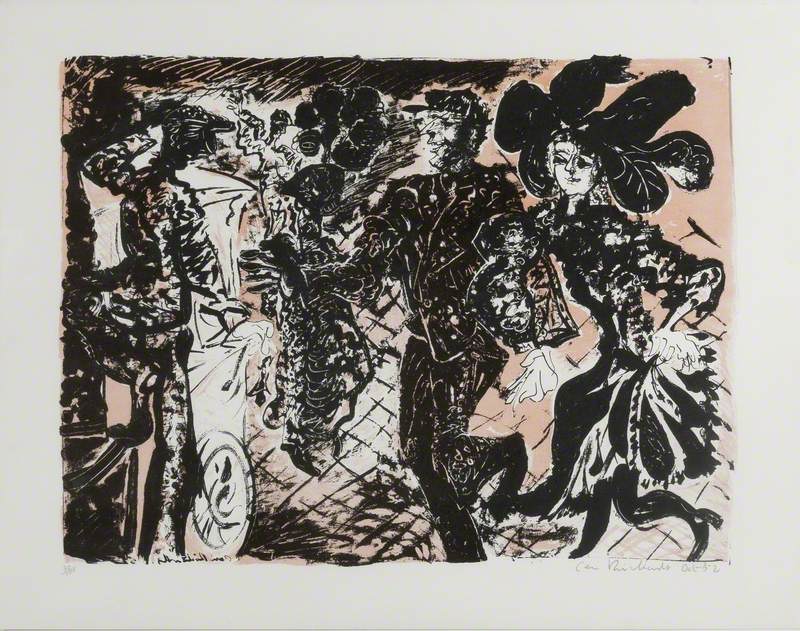

In his final years, nature, music and poetry continued to converge. On the death of his friend, the poet Vernon Watkins, in 1968, Richards painted Music of Colours, White Blossom, after Watkins' poem of the same name. He also returned to the theme of Beethoven in a late series of prints and produced a group of lithographs based on characters from Dylan Thomas' Under Milk Wood.

In 1960, he wrote 'One can say that all artists – poets, musicians, painters – are creating their own idioms for the nature of existence, for the secrets of their time.' Richards' persistent and ingenious exploration of these ideas has made him one of the most individual and underrated voices in twentieth-century British art.

Bryony White, curator

This content was supported by Jerwood Foundation

Further reading

Mel Gooding, Ceri Richards, Cameron & Hollis, 2002

Mel Gooding, Ceri Richards, Tate Gallery, 1981

Exhibition catalogue for 'Ceri Richards – Themes and Variations: A Select Retrospective', National Museum Wales, 2002