'I am a painter who works as a sculptor,' Anish Kapoor once said of his practice. While that paradoxical quote from a 1990 interview referred to the importance of colour in his work, now the opportunity has arisen to explore the artist's long-standing relationship with canvas.

This autumn, Modern Art Oxford opens an exhibition of recent painted works. Yet while this show covers the past couple of years, its curators argue 'Anish Kapoor: Painting' sheds light on the subject's wider concerns, as the artist has continued to paint throughout the four decades of his career to date.

© Anish Kapoor. All rights reserved, DACS 2021. Image credit: Ben Westoby

Installation view at Modern Art, Oxford

While his painted works have been rarely seen in public, Kapoor has gained renown as one of our most influential living sculptors, thanks to such key works as Marsyas, which stretched across the Turbine Hall in Tate Modern, London, in 2002–2003, his controversial exhibition at the Palace of Versailles, France, in 2015 and the massive ArcelorMittal Orbit structure that since 2012 has dominated east London's Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park.

© Anish Kapoor. All rights reserved, DACS 2021. Image credit: Fred Romero, CC BY 2.0 (source: Flickr)

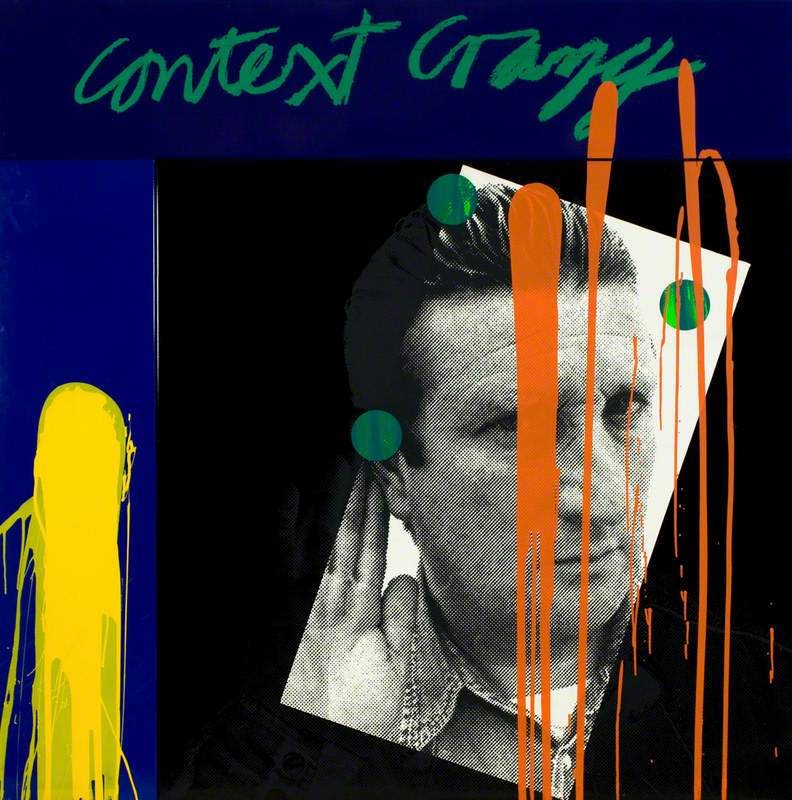

Dirty Corner at the Château de Versailles

2015, installation by Anish Kapoor (b.1954)

Dirty Corner was one of several pieces by Kapoor installed at Versailles, but it was this massive, flared steel tube facing the chateau's front that attracted protests for its suggestive shape. Nicknamed in some quarters as 'the queen's vagina', it was repeatedly vandalised, including being daubed with anti-semitic graffiti.

Born in Mumbai, India, since the 1970s he has lived, studied and worked in the UK. Towards the end of that decade, Kapoor began to make a name for himself with intimate, floor-based geometric forms that were often covered in raw, powdered pigment, as is the case with White Sand, Red Millet, Many Flowers (1982), an installation using cement and wood devised for Modern Art Oxford's group show that year 'India: Myth & Reality', where Kapoor joined a young generation of pioneering artists representing the country of his birth.

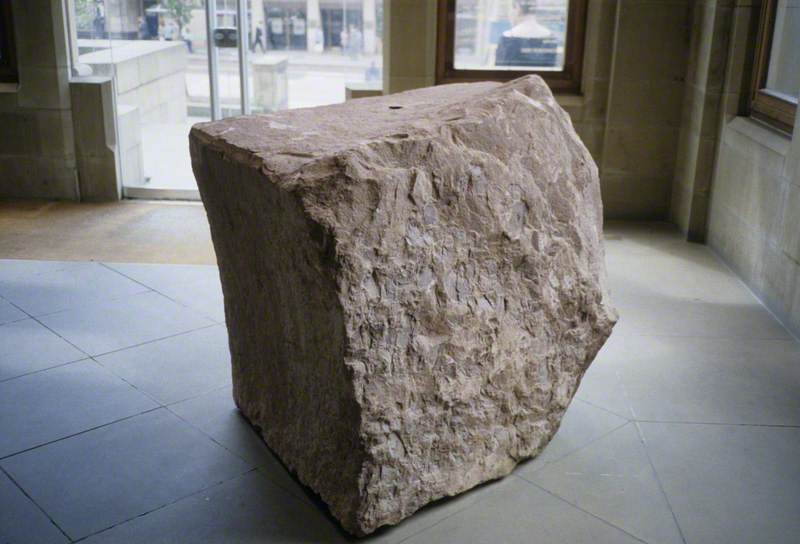

© Anish Kapoor. All rights reserved, DACS 2025. Image credit: Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London

White Sand, Red Millet, Many Flowers 1982

Anish Kapoor (b.1954)

Arts Council Collection, Southbank CentreWith access to a larger studio space, Kapoor's work became more ambitious in scale and made use of a wider range of materials, including stone. Increasingly, he moved towards focusing on single pieces that allowed him to explore ideas around space, both the space that objects occupy and contain within themselves, especially through the creation of illusory voids.

A year before he won the Turner Prize in 1991, the artist represented Britain at the 44th Venice Biennale with Void Field, which featured sandstone rocks with holes in the upper side filled with dark pigment, an example of which is held by Leeds Art Gallery.

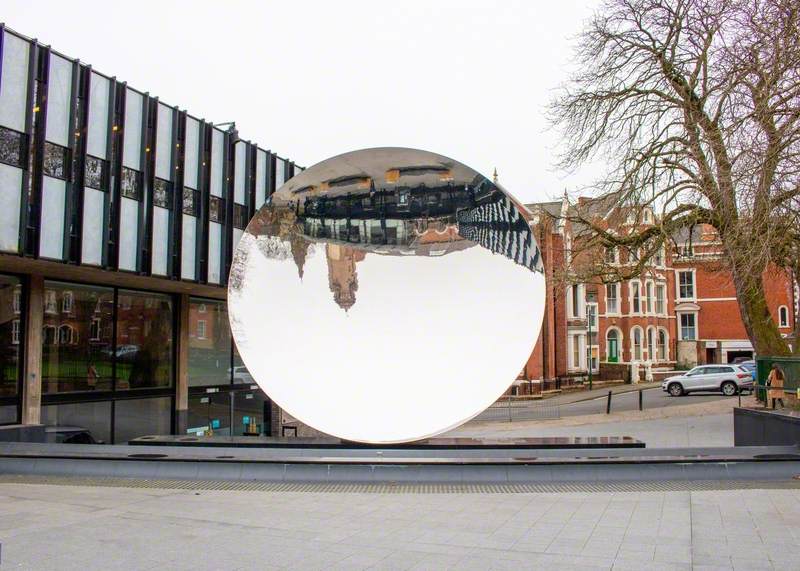

As well as drawing viewers into his voids, Kapoor often uses mirrored surfaces to play different optical games, this time to warp our sense of the world around us and our position in it, as with the huge concave dish Sky Mirror (2001) sited outside Nottingham Playhouse.

Elsewhere, the artist has also committed himself to researching novel and cutting-edge materials. His use of viscous silicone and wax has been used for his more visceral sculptures, suggestive of our bodies' interiors. Most striking have been his kinetic works, notably Svayambh, smearing red wax across gallery doorways since 2007, and his playful paint-gun cannon piece Shooting into the Corner (2008–2009)

#artworkoftheday Anish Kapoor's 'Svayambhu', 2007, features a slowly moving wax block which fills the space with a trail of bright red paint. https://t.co/liT4ay76Q2 pic.twitter.com/i2ioD3i89I

— Aesthetica Magazine (@AestheticaMag) January 24, 2020

The past couple of decades have also seen the sculptor take on a series of monumental public interventions, including the 110-metre-long, stainless steel Tenemos (2008–2010), devised with artist/designer Cecil Balmond and based at Middlesbrough dock.

© Anish Kapoor. All rights reserved, DACS 2022 & Cecil Balmond. Image credit: Helen Crute / Art UK

Anish Kapoor (b.1954) and Cecil Balmond (b.1943)

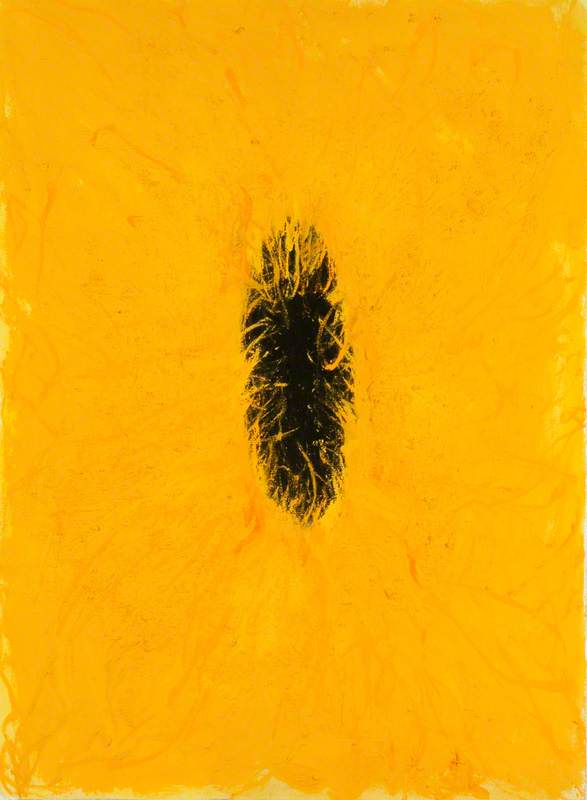

Middlehaven Dock, Priestman Road, Middlesbrough, North YorkshireDuring this time, very few of Kapoor's painted works entered the public sphere. Untitled from 1990 held by Bradford Museums and Galleries shows the artist's interest in voids extended to two-dimensional surfaces, here explored with acrylic, ink and pigment on paper. Its particular shape, one that Kapoor has repeatedly returned to through much of his career, seems to allude to female sexuality, and beyond that to the mysteries of life and its origins.

Much of his work suggests an interest in our corporeal nature, with allusions to various organs and orifices, helped by his use of a rich red tone that brings blood to mind. It is important, though, to note he has always been wary of attaching specific meanings to his abstract art.

This has remained the case as, in the past few years, Kapoor began to exhibit pieces on canvas, notably at shows held by Lisson Gallery, London. Whether those works on display in 2015 could be classed simply as paintings is debatable, as the degree to which the thick layers of silicone and resin erupted from the surface meant they occupied three-dimensional as much as flat space. If anything, they seemed to resonate with his earlier installations Svayambh and Shooting into the Corner.

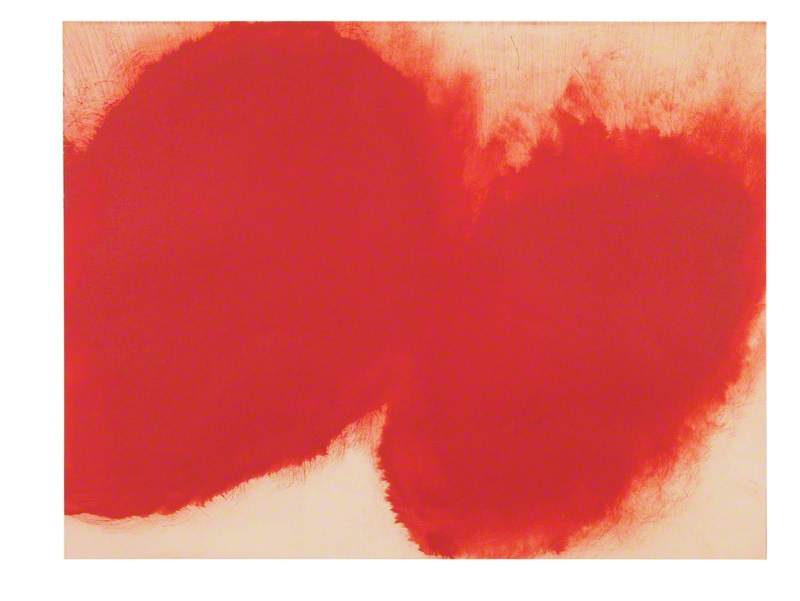

An exhibition of the artist's work at Lisson in 2019 displayed canvases with more gestural brushwork in oils that were almost figurative – seeming to depict, as the Lisson noted, 'swollen and fecund organs that ooze and leak from their dark interiors'.

© Anish Kapoor. All rights reserved, DACS 2021. Image credit: Courtesy of Lisson Gallery

Installation view at Lisson Gallery, London

Kapoor's work currently on show in Oxford as well as at Lisson dates back to 2020, suggesting a more urgent interest in painting. Again, dense layers of pigment and resin provide a sculptural quality to some of his works, though there is more tonal variety on view.

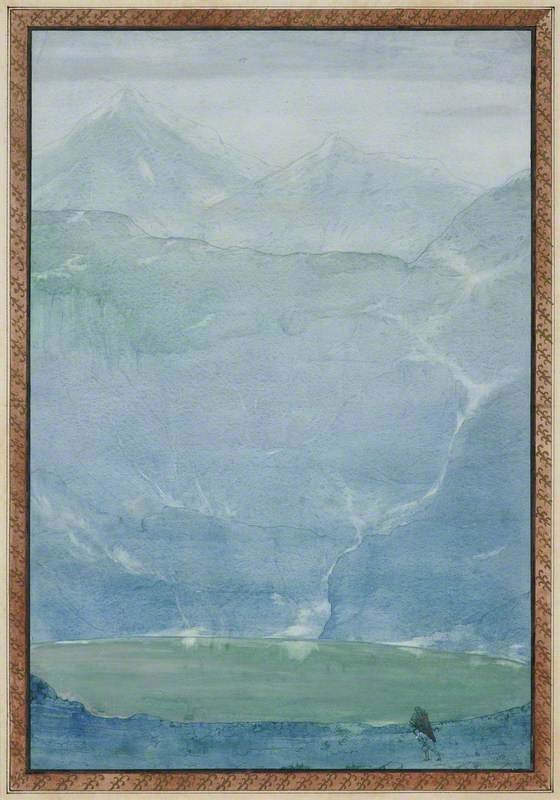

Kapoor's bright red contrasts with an earthier palette that hints at mythic landscapes, perhaps J. M. W. Turner's sublime Romanticism. In introducing its exhibition, the Lisson points to two particular series of works that evince this subtle figurative bent. Both are turbulent and ominous, especially the set with sulphurous yellows and ashen greys that suggest erupting volcanoes. Here, the earth itself is bleeding.

Image credit: Tate

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

TateThese are contrasted, the Lisson proposes, by a pair of works where one can imagine moons rising over distant peaks, symbols that hint at menstruation, linking back to Kapoor's previous meditations on life and its origins. Thinking about when these pieces were made, it is hard not to draw a connection between the artist's preoccupation with the vulnerability of our bodies and the situation we all found ourselves in – facing the enormity of the pandemic with its death counts and restrictions that kept many of us at home and Kapoor in his studio, where many of these recent works have been created.

In the catalogue for the Modern Art Oxford exhibition, its Chief Curator, Emma Ridgway, writes that Kapoor's painting, rather than a separate activity to his sculptural work, is in fact at the core of his vision and approach to art. She illustrates this by guiding us on a visit to the artist's studio, its sequence of expansive, white-walled spaces each dedicated to a different aspect of production.

© Anish Kapoor. All rights reserved, DACS 2021. Image credit: Courtesy of Modern Art, Oxford

Anish Kapoor Studio, 2019

Ridgway leads us through the discreet street entrance and up narrow stairwells, 'navigating between a dense array of artworks and experiments'. Kapoor is on a quest to research the possibilities of various media, though not in an emotionless, scientific manner. Instead, there is a spiritual aspect to the way he fits painting into his everyday life.

'This site is the alchemical lab where Kapoor's internationally known sculptures are made with us, the viewers, in mind,' she explains. 'Yet it is the daily ritual of his painting practice, for the most part hidden from view, that provides the integral connection between the broad oeuvre of his sculptural works.'

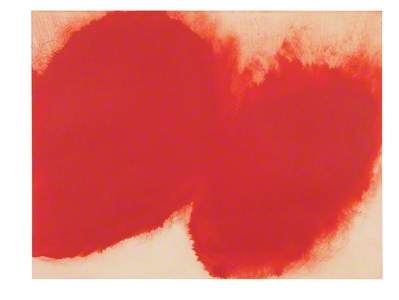

© Anish Kapoor. All rights reserved, DACS 2021. Image credit: Stephen White & Co.

The world trembles when I retrieve from my ancient past what I need to live in the depths of myself

2020, oil on canvas by Anish Kapoor (b.1954)

The curator also points to a major difference between Kapoor's emotive paintings and his more conceptual sculptures. The latter forms, painstakingly designed and constructed, lack the imprint of the artist's handiwork, thus removing the intrusion of artistic expression from our experience of them.

Instead, we are drawn into closer inspection of the works themselves (both physically in distance and in how we focus on our senses), allowing us to revel in how our perception shifts or is fooled by colours, shadings or reflections, as in the mirrored curves of Turning the World Inside Out (1995).

On the other hand, in this current crop of paintings, Kapoor reveals an intense emotionality in his dramatic use of paint. For Ridgway, he is dealing with the precariousness of our physical existence.

'They are gut-wrenching in their raw vulnerability, their red tones explicitly referencing bodily blood,' she writes.

© Anish Kapoor. All rights reserved, DACS. Image credit: Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London / Ben Westoby

Installation view at Modern Art, Oxford

There is darkness here, but also a joyousness in the instinctive act of creation. Without working to a particular brief or with a location in mind, Kapoor has worked without inhibition. By allowing these works to be shown, he is letting us into his inner sanctum.

Chris Mugan, freelance journalist

'Anish Kapoor: Painting' is at Modern Art Oxford, open from October 2nd 2021 until 13th February 2022