The paunch. The belly. The spare tyre. The beer gut. The muffin.

Idealised male beauty, fatphobia and body shaming are arguably so pervasive in today's culture that we have a range of slang to choose from when we describe masculine stomach size. When contemporary body reflection turns to art history the result can be prejudice or body positivity. It's a rich yet potentially dangerous visual source – the politics of male waistlines and body mass have played out for centuries in galleries across the country.

What do we find when we look at larger male stomach shapes in art history? What are the dangers in linking art history to today's debates on the male body?

Eighteenth-century European art offers us a fascinating and visually immediate example of the politics around male waist size – in a theory or vogue dubbed the 'power paunch'. The concept rests on a potent, wealthy and aggressive visual form of male dominance. Size equals power. For some men in eighteenth-century portraits, stomach size is not accidental or coincidental but cultivated. Weight is consciously added to physically occupy space as a demonstration of male achievement and power.

To eat to excess was a visual display of status – physically advertising masculinity, class, prowess and social dominance. In art history, the paunch becomes a potent visual symbol.

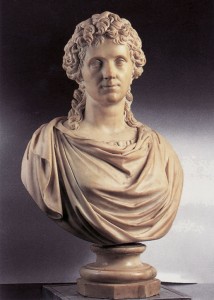

This portrait by George Romney of Brigadier-General Lawrence Nilson (1734–1811) is a prime example of the power paunch in action.

Brigadier-General Lawrence Nilson (1734–1811)

c.1791

George Romney (1734–1802)

The brigadier-general bristles with rigid authority as he stares back at us, his posture deliberate, self-aware and confident. Powdered hair, crisp white linen and opulent red regimentals frame a military man who dominates the canvas in erect pride.

Humanism and sensory awareness are achieved by Romney in the face – red flushed cheeks demonstrate perhaps exertion, or more broadly the sitter's health. A hint of a chin gives way in turn to a splendid waistcoat tailored around the stomach.

The curve of the lower torso is captured vividly in the composition – neither the brigadier nor Romney make any effort to conceal the stomach. Far from it, the stomach arguably dominates the composition, pushed out towards us in aggressive prominence.

The stomach is a visual statement, presented expertly by Romney, and no effort is spared on its treatment. Note, for example, the strain on the buttonholes towards the bottom, and the pull on the fabric. The brigadier wants us to see this – the painting associates his stomach with his might.

Nilson's personal history speaks to us of masculine dominance and colonial violence. He was the first Chief Engineer of the Bombay Army in 1777. His company took part in the violent expedition to the Malabar Coast against Tipu Sultan's forces in 1782 during the Second Anglo-Mysore War. He subsequently became the Commander-in-Chief of the Bombay Army in 1785. Military aggression, imperial wealth, control, and by extension colonialism, plays out in the brigadier's physicality. Arguably, his stomach is visually as weaponised as the sword at his side.

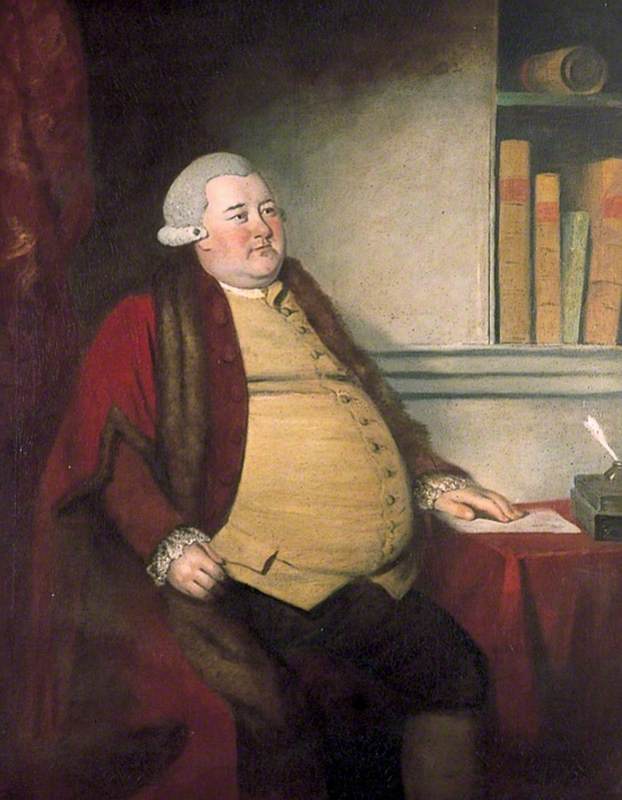

This portrait of Alderman Richard Barham (1702–1784) by an unknown artist in Canterbury Museums and Galleries is another model of power and control.

Still in use today, 'alderman' was a title used by members of councils in England and Wales, with no specific widely agreed definition until the nineteenth century. However, we know Alderman Barham held great social power – his decisions directly affected the lives of others. We find him pictured here with a pen and paper ready for his next correspondence, and hefty books in the background.

He is staged in a sumptuous red fabric, covering the desk, wall and his chair. The stomach once more is prominent in the composition. Again, as with Romney, the artist dedicates time and skill in the depiction of the waistcoat and, in turn, the stomach.

Barham personifies civic power – his physicality is visually linked to his authority. To see the stomach is to see essentially a 'member of the club' in terms of power dynamics.

As the image reinforces male power, it also excludes the viewer in equal measure – imagine, for example, seeing the wealth of weight from the perspective of eighteenth-century poverty. In a wider society where food may be scarce and economy uncertain, to attain a larger weight would be an extraordinary statement and far more visually apparent than today.

But are we reading too much into the paunch? Could stomach shape just be purely coincidental due to age, fashion or lifestyle?

Reaching an advanced age in the eighteenth century on a calorie-rich diet may explain the stomach shape and its treatment. Joshua Reynolds' double portrait of Admiral Francis Holburne (1704–1771), and his son, Sir Francis (1752–1820), 4th Baronet, however, may be a case against this.

Admiral Francis Holburne (1704–1771), and his Son, Sir Francis (1752–1820), 4th Baronet

1755–1757

Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792)

Here we find the admiral at the height of his career – a prominent commander and chief, and later parliamentarian. His stomach is gloriously encased in a waistcoat of fine material and braiding.

Deliberate creasing across the stomach material is mirrored by his son. Is this purely an example of eighteenth-century men's fashion? Or does it hold a deeper message?

Both figures arguably offer us male power play, the younger Francis demonstrating what could be seen as an echo of his father's status.

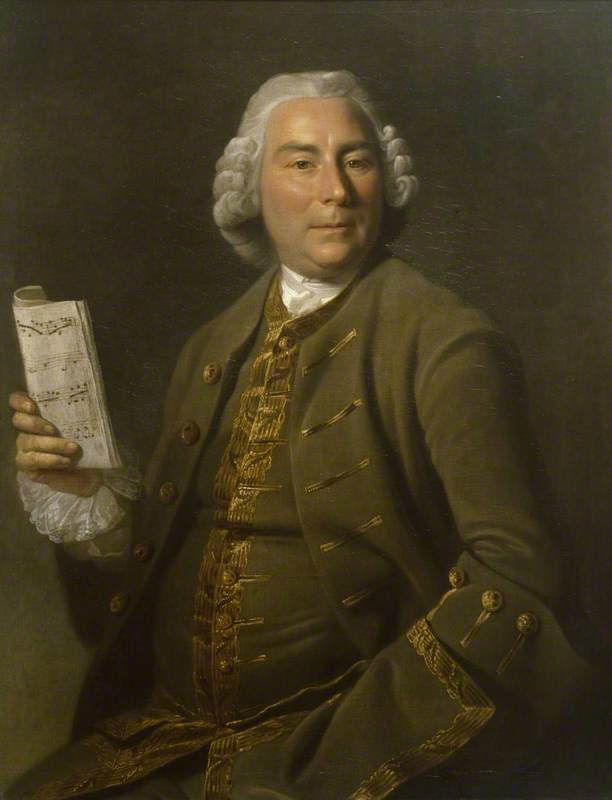

The idea that the stomach shape is simply a case of middle-aged spread is also challenged by this portrait of a young man (possibly Richard Molyneux) by an unknown artist.

Portrait of a Young Man

(possibly Richard Molyneux, d.1734) c.1730

unknown artist

A youthful figure offers the telltale body coding and artistic treatment in the creasing across the lower stomach. Eighteenth-century male body types were by no means homogenised, and we find a multitude of figures with smaller waistlines. Yet the power paunch stands out when we find it, both visually and thematically.

Stomach size morphs to take on aspirational status as associated with the class of the sitter. Sir Wolstan Dixie (1700–1767), 4th Bt, Market Bosworth, painted by Henry Pickering, dazzles in visual opulence.

Sir Wolstan Dixie (1700–1767), 4th Bt, Market Bosworth

1741

Henry Pickering (c.1720–1770/1771)

Pickering works hard to achieve a perception of aristocratic glamour and curated splendour, with the sitter's stomach intrinsic here to the look.

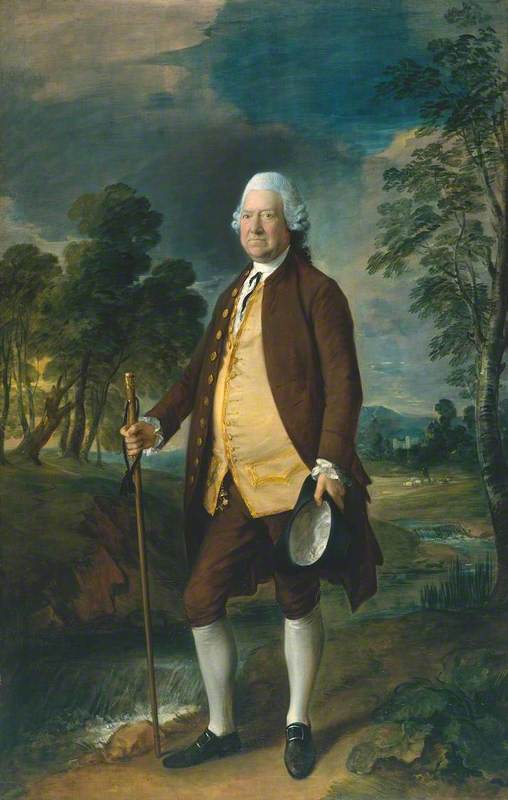

This portrait of Sir Benjamin Truman (1699/1700–1780) by Thomas Gainsborough goes one step further and arguably uses the stomach to increase gravitas in the sitter.

A contrived image of class translates visually into Truman's physicality. Gainsborough uses it to visually communicate the idea that this is what aristocratic dignity looks like, with the stomach shape again a constituent part.

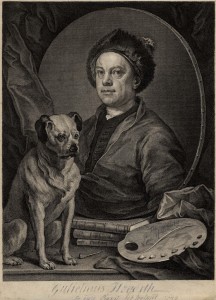

Across all levels of male power in Britain in the 1700s, we find a larger stomach shape celebrated and consciously depicted. George Romney's portrait of Sir Noah Thomas (1720–1792), alumnus of St John's College, and Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians, is a sumptuous study of a medical man.

Sir Thomas was physician-in-ordinary to George III, a figure at the heart of court power and politics. Stood in profile looking towards us, Sir Thomas had reached the pinnacle of his profession and therefore power. His stomach shape curves out through elegant grey silk – inescapable and visually commanding.

Today the NHS suggests as a general rule of thumb that men with a waist size of 94 cm or more are more likely to develop obesity-related health problems. To see the waistline of a medical professional such as Sir Thomas and contrast this with contemporary health discourse is to also see the dangers of its depiction.

Medical objectification denies us a multitude of personal lived experiences and advocacy in terms of men's bodies. Body types as seen in the eighteenth-century power paunch are, from a health perspective, potentially harmful – yet this heath concern often wraps around identity politics in a toxic web of prejudice against having a larger build.

While art history could be misused to condemn others or be a source of prejudice, we should however (and must) also see that body shapes in art are an available resource to those who celebrate that form or find body positivity.

Art history has the potential to be weaponised to support a multitude of views – however, the eighteenth-century power paunch reminds us that much of art history exists within a context of male power and identity.

Jon Sleigh, freelance arts educator