The male-presenting sailor occupies a unique place in the queer visual art canon. Instantly recognisable in mass media, the romance or homoerotism of the mariner sits with us in pop culture today. We repeatedly see the figure of the male sailor, in all its idealised glamour in art history, linked to queer identity. How has art contributed to the gay male mythology of the sailor? Is queering the male sailor empowering and thrilling, or increasingly a redundant stereotype?

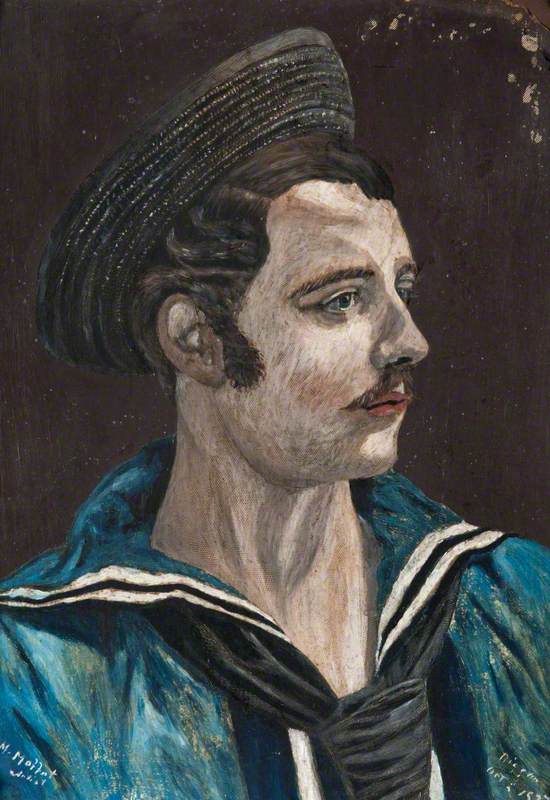

An Ordinary Telegraphist, Maurice Alan Easton

1944

Henry Marvell Carr (1894–1970)

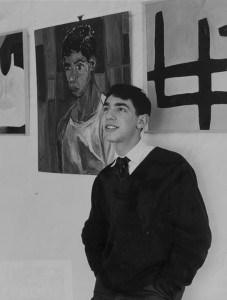

Where does the queer link come from? Henry Marvell Carr at the National Maritime Museum models the archetype of the idealised male sailor for us. An Ordinary Telegraphist, painted in around 1944, taps into the essence of the sailor as iconic. The figure of the sitter Maurice Alan Easton radiates male glamour. Idealised, vigorous, masculine, noble, brave, disciplined, able, virtuous, protective, handsome, strong – Maurice embodies a litany of symbolic or fantasy qualities we project onto his physicality.

The combination of what the uniform represents and the male beauty here is palpable. Contrived to be as appealing as possible, Maurice is transformed from the civilian life he formerly occupied as a railway bookings clerk from Oxfordshire into a man of action stationed in Naples.

He transcends 'normality' – becoming fetishised by travel, danger, and an all-male environment. The artist Carr was conscious of the sitter's appeal (Easton was specifically chosen by the artist) and his image went on to feature as a poster for a Navy Leagues exhibition in 1946. Consciously or unconsciously, the artist offers us the quintessential gay male fantasy from history.

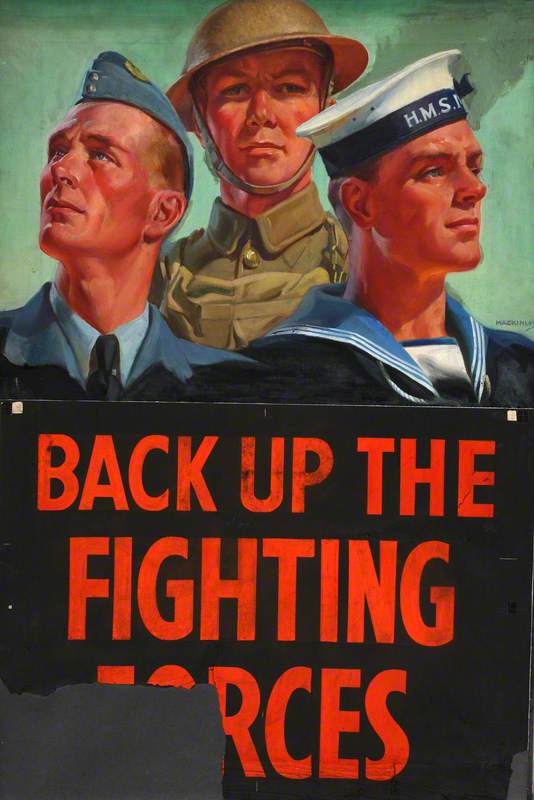

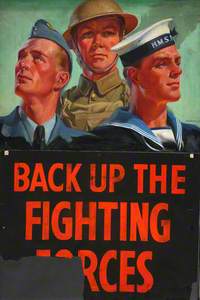

The artist MacKinlay, through this poster at the National Archives, adds to this with nationalistic purpose.

The handsome appeal of the sailor is not only aesthetic but also political. Male beauty is a propaganda tool and aspirational – to be heroic is to be beautiful. Set up as national figures for admiration, queer romance finds a visual language for expression.

Let's consider the process of queering the sailor in art and its function. To be a mariner, or more explicitly to escape the societal conventions of life on the land was powerful indeed and recognised by queer audiences historically. Same-sex desire and affection was a facet of life at sea – in single-sex environments freedom of movement and access to different cultures afforded more options. Gay bars in ports around the world mirrored this, as did the spread of the queer language Polari (a way to speak openly and in code without overtly incriminating yourself).

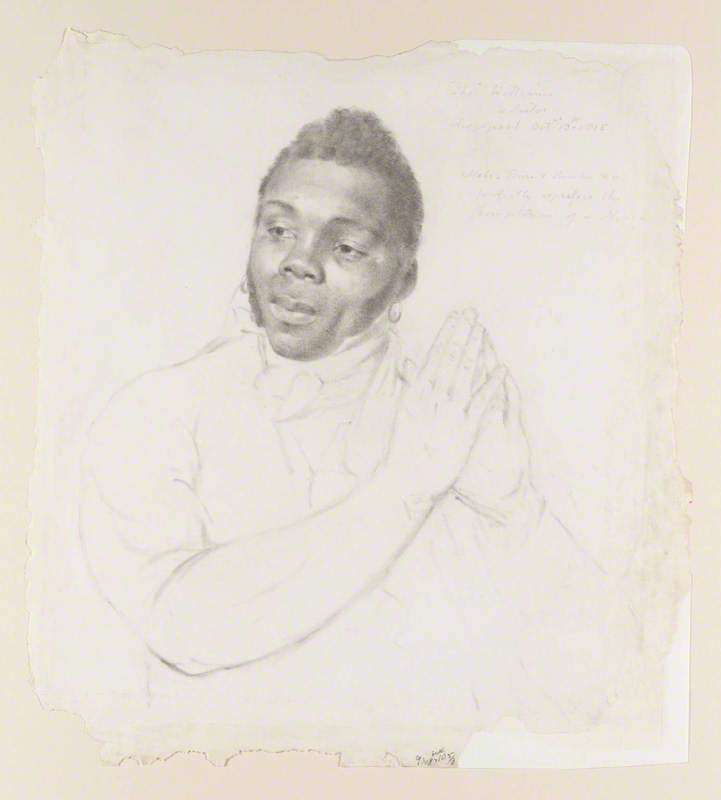

How much do historical artworks speak to this? Before the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1967, they simply cannot explicitly do this. Instead, we project the gay male experience onto these figures. Is it fair to do so? Consider for example W. M. Ladbrooke (active 1939–1945), Able Seaman, Merchant Navy by Bernard Hailstone at the National Maritime Museum.

W. M. Ladbrooke (active 1939–1945), Able Seaman, Merchant Navy

c.1943–1944

Bernard Hailstone (1910–1987)

Bedazzled by the overt masculinity and glamour of this image, do we presume the sitter was either gay or straight? That he lived a binary gender existence? Further, do we acknowledge that he was witness to a multitude of queer voices and experiences around him that are now lost? For communities today, often to queer a piece of art is a powerful and valid moment of expression counterbalancing historical erasure.

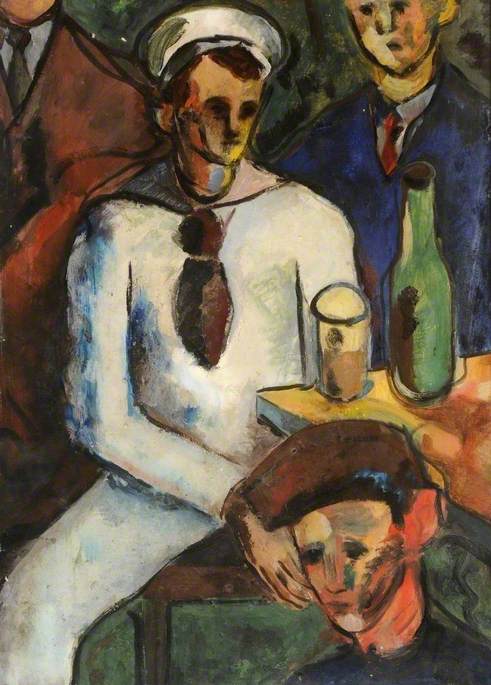

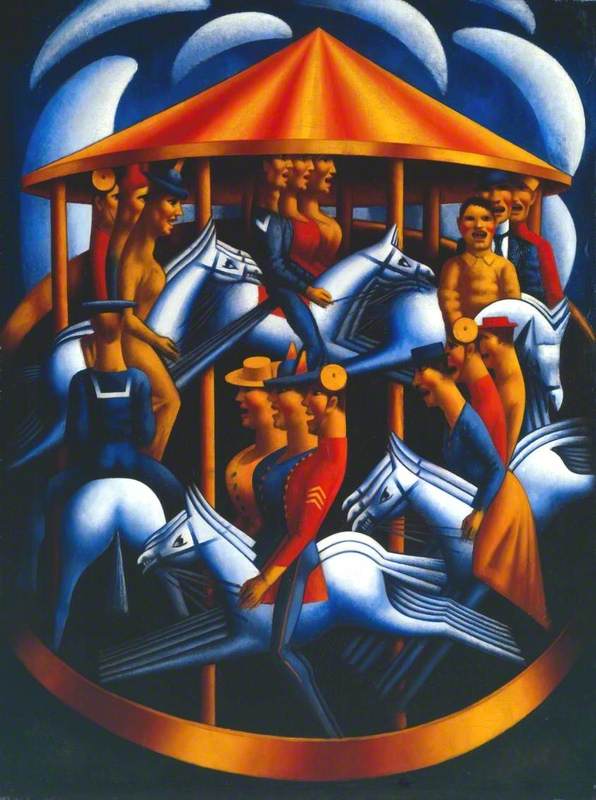

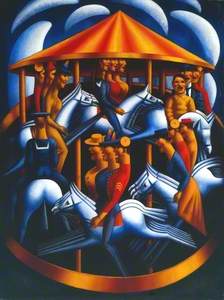

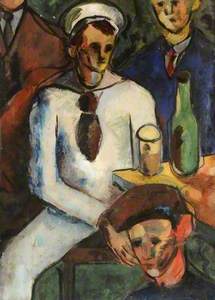

When queering the sailor, context can often be key. Artist Mark Gertler, in this c.1916 work now at Tate, offers us an exuberant nightlife scene complete with sailor imagery.

A multitude of figures and gender identities are locked in the spinning thrills of Merry-Go-Round. Set in Hampstead Heath Park in London, this piece directly references an event held on behalf of wounded soldiers, and from this the horrors of war. It's an uncomfortable piece, sharp with modernism and underlying intensity.

Here, too, we find an explicit link with gay male communities – the park was a well know cruising ground in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Gertler lived near Hampstead Heath from the winter of 1914–1915 – how conscious was he that the landscape he painted here was heavily coded in gay male sexuality? Again, whether conscious or unconsciously, the sailor sits visually within a homoerotic landscape.

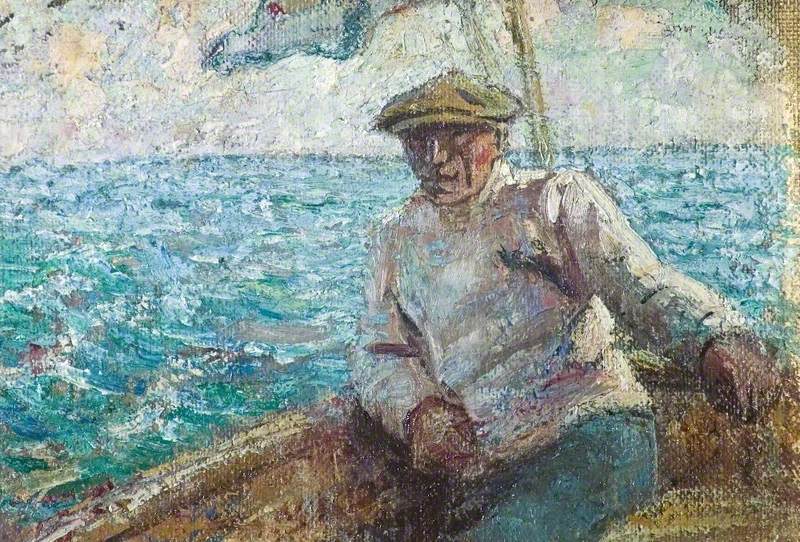

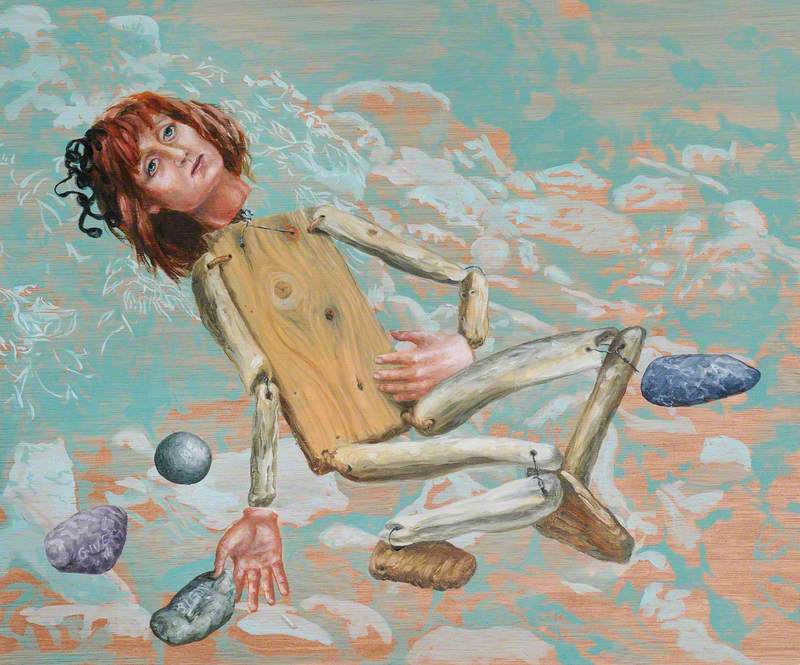

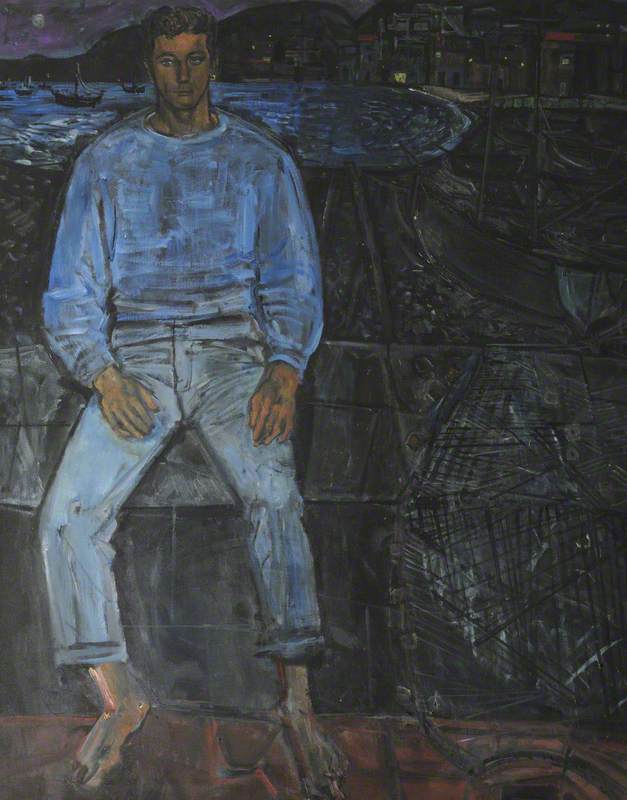

Another art reading can be found in the incredibly beautiful depiction of 'David', an Unknown Man Sitting Barefoot on a Waterfront (said to be a Portuguese sailor) by John Minton (1917–1957), in the collection of Balliol College, Oxford.

'David', an Unknown Man Sitting Barefoot on a Waterfront

(said to be a Portuguese sailor) c.1950

John Minton (1917–1957)

Male eroticism arguably echoes within this work, made before the legality of gay expression. Specifically, the male beauty of David is framed within a dark and enveloping nightlife. His barefoot physicality waits alone, framed by the port and other ships. His brooding presence is made more sensory using colour – deep blues, blacks, purples and browns applied with deliberate and confident brushwork.

Perspective shifts and alters around the figure, seemly to enhance the sitter whilst making the surroundings more densely packed. It's a maze of shape, texture and poised with expectation. Where some may see a man at rest in the evening, others may see a coded reference to gay male sexuality and cruising for sex hidden by night.

A stereotype too far? Reading artworks from gay male perspectives, however, can risk occupying a two-dimensional or prejudicial view on the gay male experience. That to be gay, or resort to same-sex love or desire while at sea, is some sort of default or secondary option to being heteronormative. A lesser option perhaps, stigmatised in the lusty sailor trope.

Presumed or weaponised homoeroticism for comedic effect masks a deeper and more nuanced experience of gay male life that contemporary audiences expect today – one that includes homo-affectionate friendship, romantic connection, and intersectional identity.

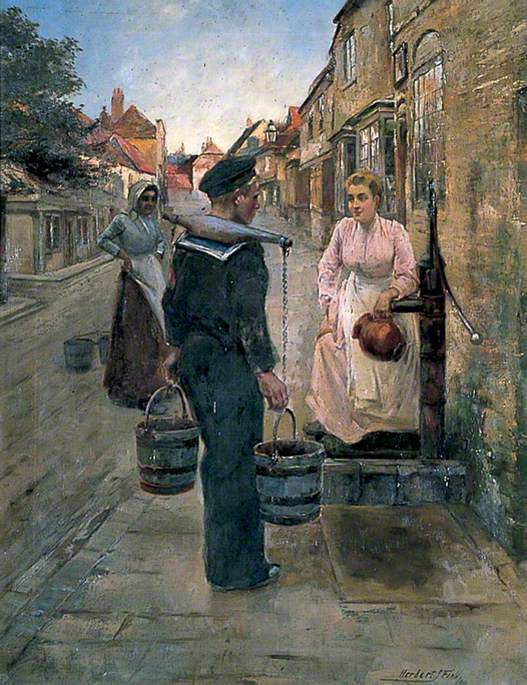

Seen within the Government Art Collection, another work by Bernard Hailstone offers a fascinating counterpoint in consideration to the artist we began with, Henry Marvell Carr.

Able-Seaman David Addison, Trawlerman

c.1943–1945

Bernard Hailstone (1910–1987)

Able Seaman David Addison, Trawlerman arguably breaks the binary of male presenting sailors and is rife with ambiguity and coded messages. Addison presents to us without the macho bravado – no disciplined stance or flexing or his body.

Instead, curving lines make up an almost rakish form. A sensibility of poised consideration greets us, elegant and curated lines of the form are both strong yet not overly masculine. The wedding ring however is unmistakable and prominent. A queer sensibility radiates from this image – markedly male and maritime, yet beyond an aggressive heterosexual stereotype.

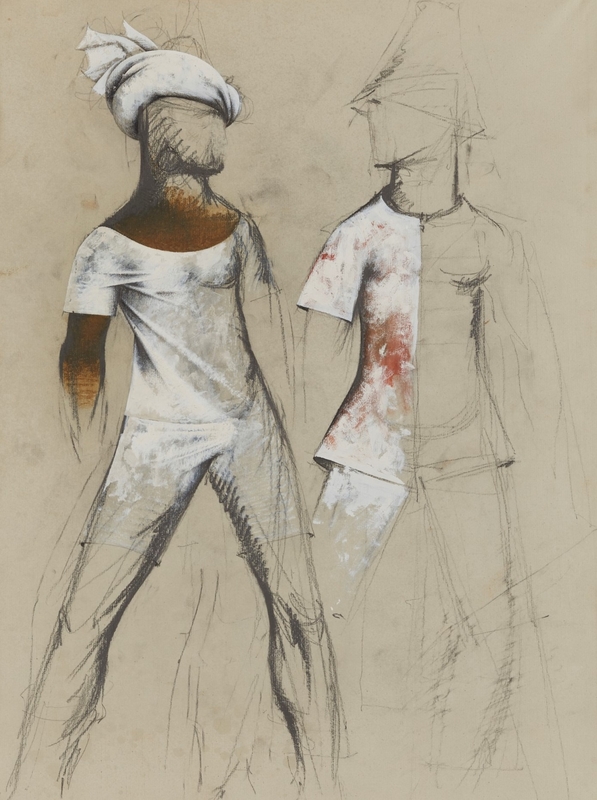

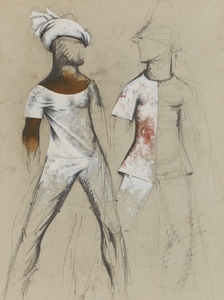

As the queer association with sailors endures, so too does its artwork. The UK's partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1967 is exactly contemporary with this depiction of Sailors by Erich Kondrak.

Both anonymous figures are costume designs for sailors from Glyndebourne's opera production of Francesco Cavalli's L'Ormindo. These bold and perhaps fetishised male forms arguably demonstrate that ultimately the queer iconography of the sailor continues – adapting with queerness as both evolve. Perhaps in its endurance, we find its relevancy?

Jon Sleigh, freelance arts educator