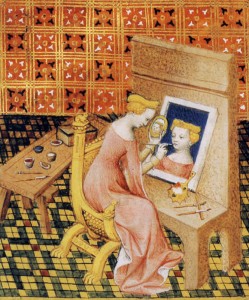

Windows have been used in paintings to mean lots of different things. As an exhibition at the Paul Mellon Centre makes clear, the window serves as a boundary between inside and out, as well as a framing device. Windows are a symbol of being perceived, but sometimes, despite being seen, we can still feel isolated. A window then, can be a lonely thing. We look out, but people can look in at us. Windows in art can serve as mediators for self-image, they ask us how we want to be seen by others, and to consider the boundaries between our public and private selves.

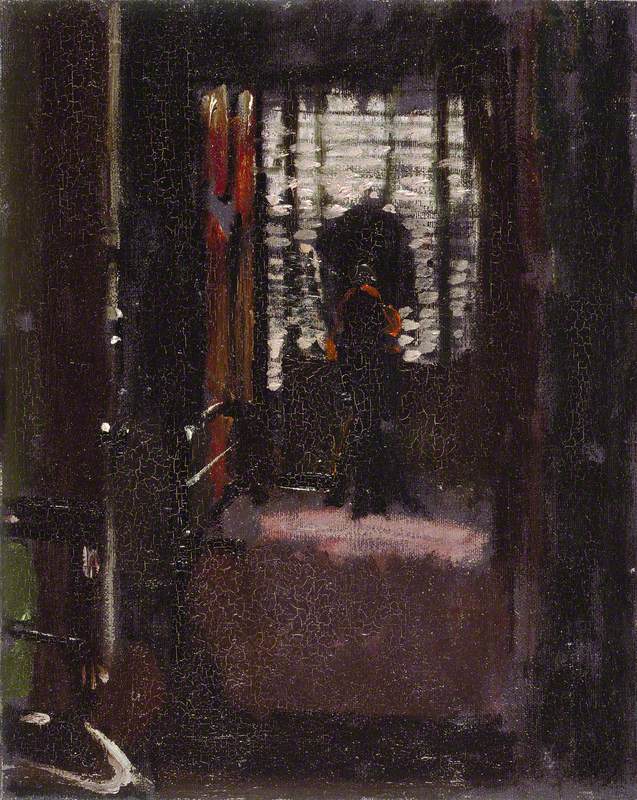

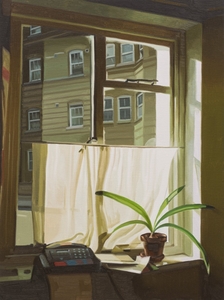

Mike Silva's artworks capture longing for connection. Many of his works use light filtering through empty space to represent this feeling – evident in his current exhibition at the De La Warr Pavilion. In Silva's Window (2023), part of the Jerwood collection, we look out to a block of flats, dark windows staring back at us.

Despite the light illuminating the half curtain, this also acts as a further shield. There are no people in this image, just the spectre of being seen.

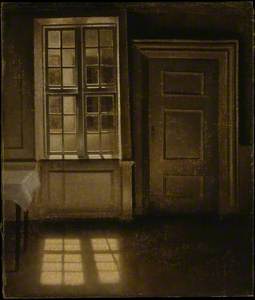

One of the masters of loneliness is Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi. In Interior, Sunlight on the Floor (1906), there's an inescapable sense of absence. The light inside Interior's room is dark and dull – the light outside by contrast feels warm and clear. It's both eerie and comforting. In Silva's Window, the sense of being observed comes from the windows across the street, but in this work, it almost feels as if the window itself is watching us.

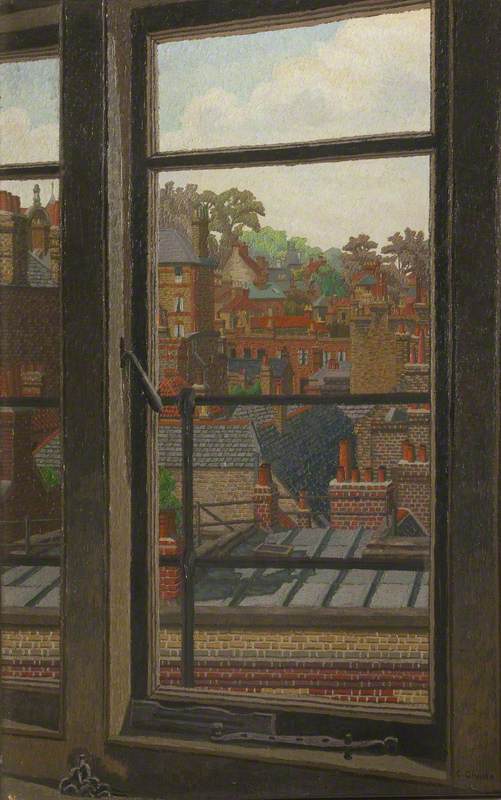

In this work from 1924 by John Quinton Pringle, the window is the focus, but there's no focal point. The muddy brushstrokes and bleak colours create a melancholy, hazy atmosphere. There is only the sparseness of the grey, peeling walls around the window, and the streaks of mud that stripe the grass. Pringle's composition is one of isolation with no visual markers to break the monotony.

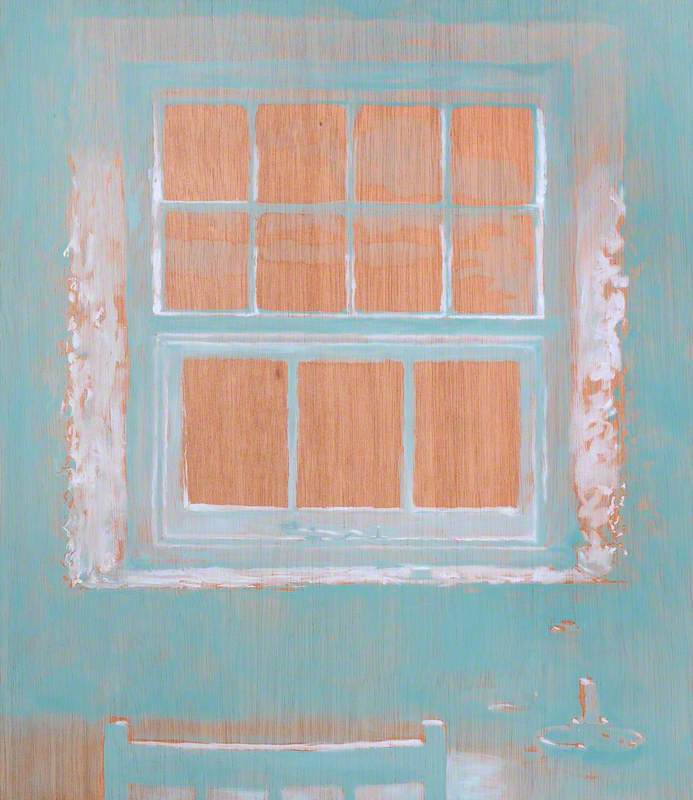

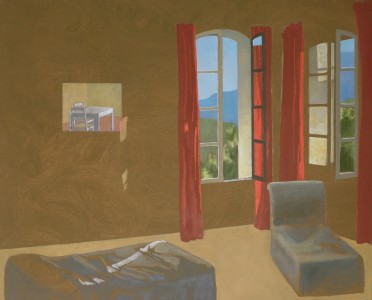

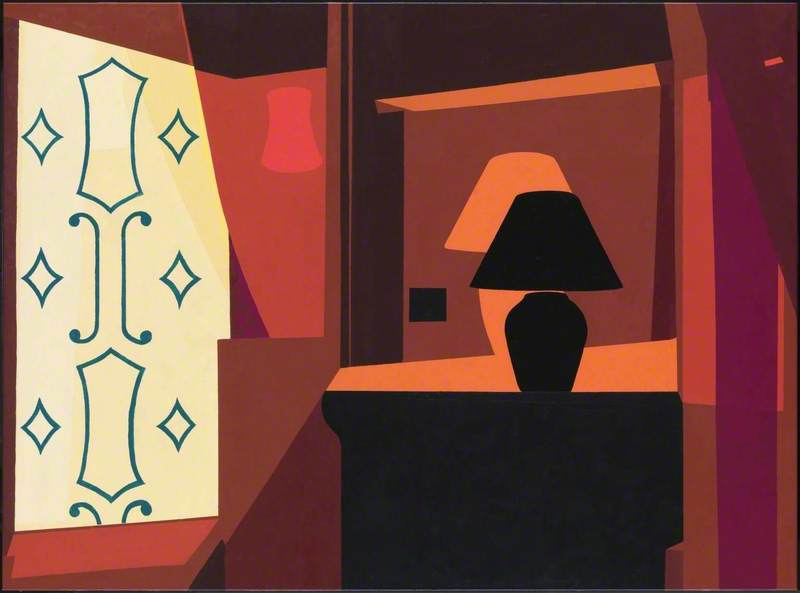

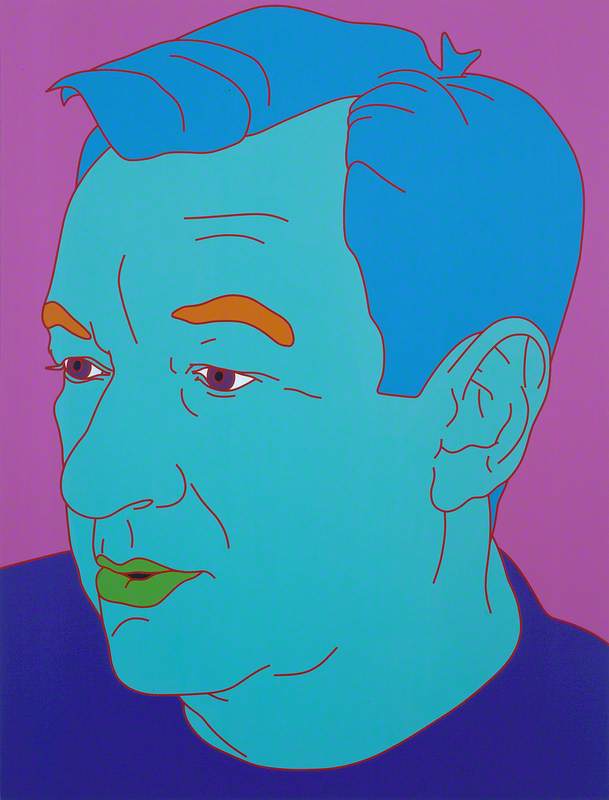

In contrast, the sharp lines and vivid colours of Patrick Caulfield's 'Interior' series from 1971 shows the stark passage of time across a day. Interior: Morning, Noon, Evening, and Night reveals how the light shifts and deepens but the view of the window and lamp stays the same. Our perspective is one of unchanging solitude, absent from company.

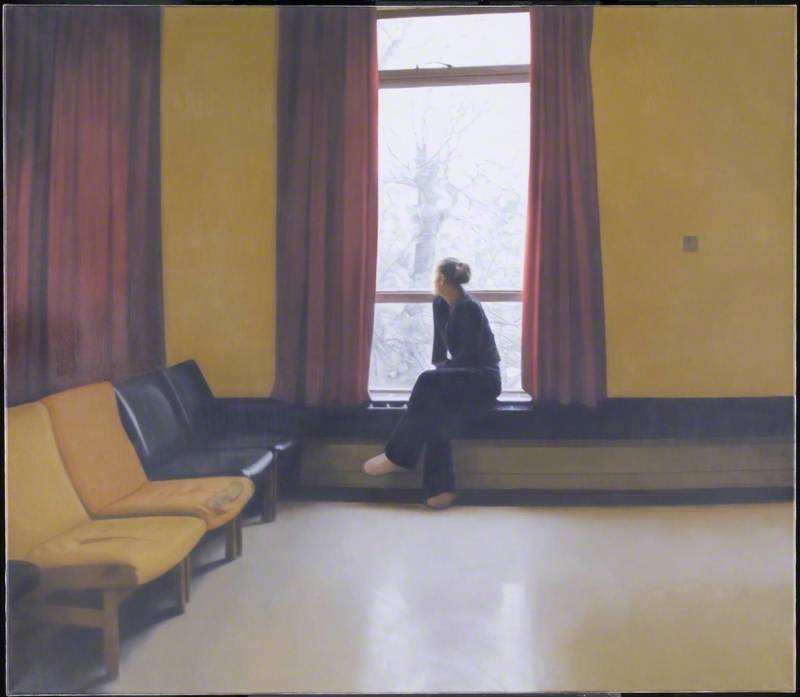

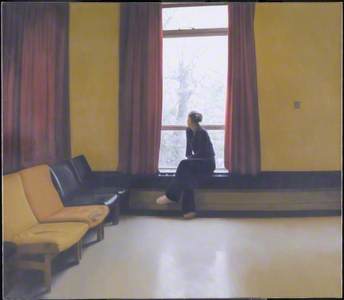

Combining visual spareness with a lone figure, Silvia Rosi's Neither Could Exist Alone series from 2020 recreates her experience of being stuck inside her London flat during lockdown, feeling trapped and missing her family and community. Rosi describes the sensation of being a voyeur and object simultaneously: she looks out of the windows and is also looked at through them by the viewer.

Her actions, such as reading a book, are curated to look private, and as such ask us which behaviours we perform and which are organic. Performance itself is a kind of isolation.

Shopping centres are places where, more often than not, we are surrounded by people but are alone. In Philip Westcott's Salford City Shopping Centre (1982), shoppers walk past and wait outside phone booths. The people in the phone boxes are publicly visible but enmeshed in their own private lives. We do not engage, and only interact out of necessity.

The titular figure of this painting, Mary Morris, is witness to many private lives in a commercial context. This warm, welcoming painting of Morris, a Post Office and shop worker who has formed meaningful relationships in her changing community, also suggests the alienation in customer service; city dwellers will rarely find the connection that this painting celebrates.

Mary Morris, Post Office Assistant

2000

Anthony Morris (b.1938)

Yet, there is still a barrier separating her from the public: the perspex window serves as a symbol for the public persona we put on at work and the private inner self.

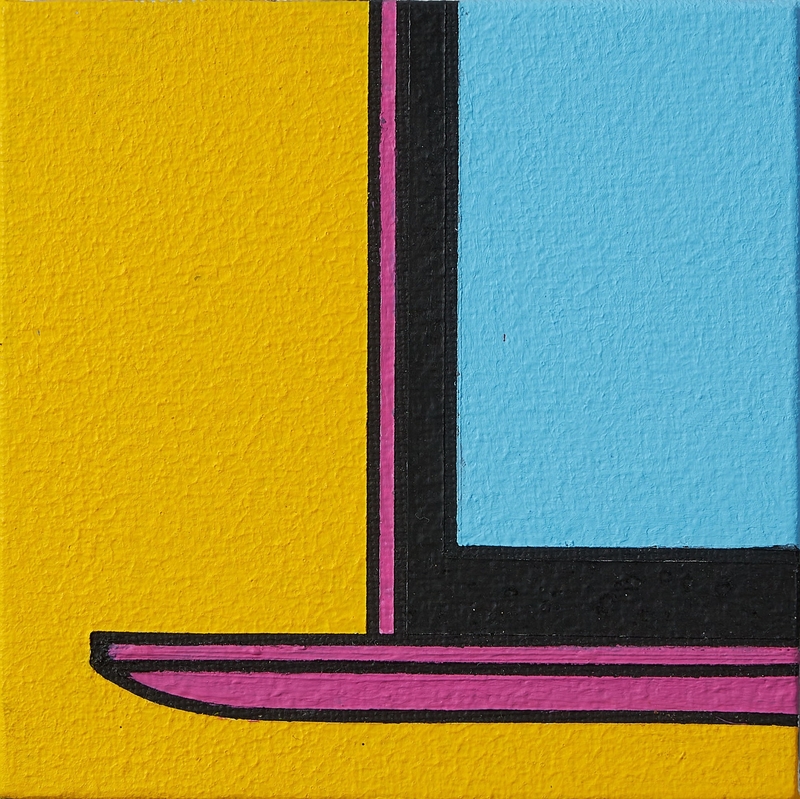

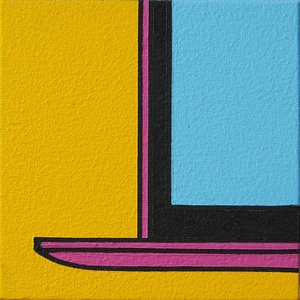

This alienation can be exacerbated by technology. In an age of digital communication, the performance of contextual personas has never been more prevalent. In Michael Craig-Martin's Untitled (Laptop fragment miniature) from 1921, we only see a corner of the screen, alluding to how digital representations of life can often be incomplete or misleading. The bright, popping colours serve as the promise of connection, but ultimately, this window reveals nothing. We are only really sharing a fragment of ourselves.

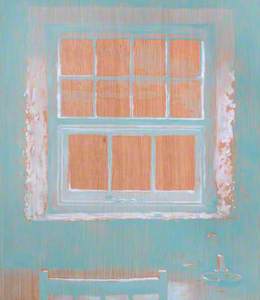

There's a physical reminder of this in the realist painting Cocoon (2020) by Michael Power. This window is viewed from the outside, the mint green of the frame a stark contrast to the dirtied and cracked external wall.

What are we proud to show, what do we want to hide? The lace curtain is a symbol of nosiness, of gossip and petty judgement. It is a shield and a barrier. By hiding behind it, you can exclude yourself from the outside world.

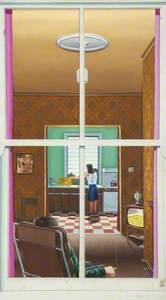

David Redfern's works often use window frames as a device for separation. In Look through Any Window (1976), we are able to look all the way through a couple's house, through the front window and out the back. The pane of the first window forms a barrier between husband and wife. Their attention is drawn away from each other by the other windows; the wife looks out toward the sky and the husband watches a football game.

In The Bank Clerk, Redfern covers the teller's mouth with the window pane and splits his face from his hand. The lines he draws show physical separation, but also highlight the isolation that can come from adhering to societal norms.

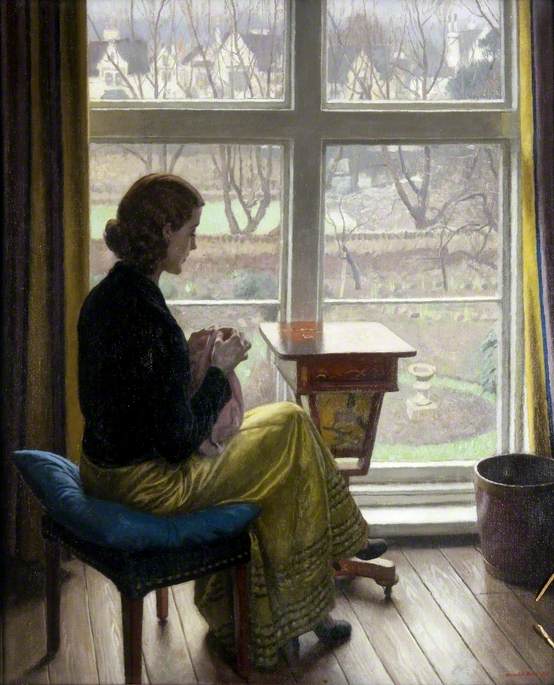

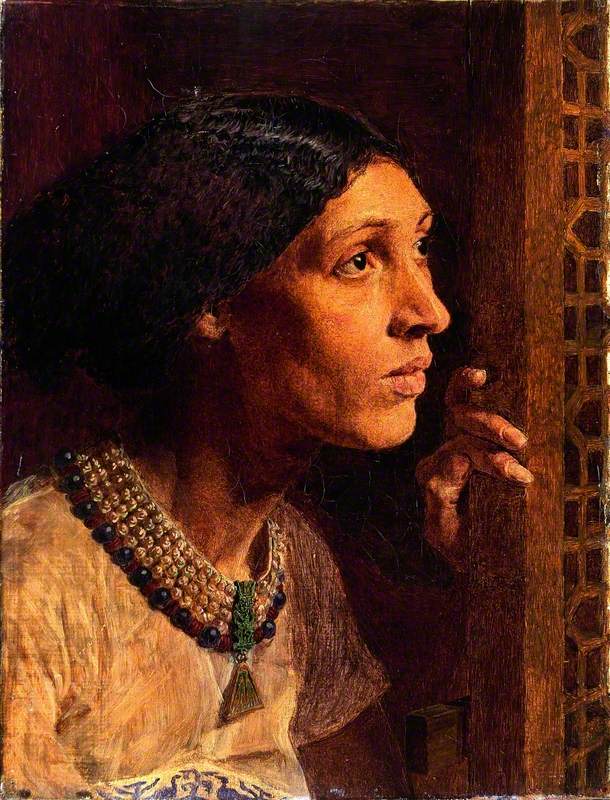

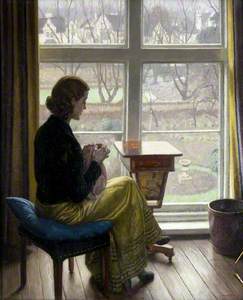

Loneliness through incorrect perception is keenly felt by women, whose exteriors are often examined as indications of character. Perhaps this is one reason why there is a long tradition of depicting women beside windows throughout art history. The women in Harold Knight's A Window in St John's Wood (c.1932) and Ernest Townsend's Summer Morning Interior (1917) are observers and we, in turn, look at this relationship between window and woman.

We catch both women in moments of distraction and introspection: one is embroidering and the other is adjusting some flowers. These are both hobbies that women would have been steered towards, but how can we know that these women perform them out of enjoyment, or because they feel they must?

The mural, A Window to the Sea by Elisa Capdevila, features a lonely window, but it's also a hopeful one. This is another post-lockdown work, dated 2022, and Capdevila wants us to look for the connections we lost with the world over those years. The figure in this image is looking out of a window and towards the sea. The real windows surrounding Capdevila's painted one belong to an abandoned building beside a shopping centre in Aberdeen.

This unoccupied building and the direction of the subject's gaze remind us that loneliness isn't just about being alone; it's a lack of personally meaningful connection.

Looking out of a window, we are looking inside of ourselves. These artists, and many others, are asking us to reflect on how we wish to be perceived in the spaces we claim as our own and what we want to gain from the world around us. While many of these paintings evoke loneliness, this feeling is essential in reminding us that the world exists outside. It is always a better place with us being our authentic selves within it.

Olivia Moinuddin, arts writer

''What Light Through Yonder Window Breaks?' The Window as Protagonist in British Architecture and Visual Culture' is at the Paul Mellon Centre, London, until 28th February 2025

'Mike Silva' is at the De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill, until 26th January 2025

This content was supported by Jerwood Foundation