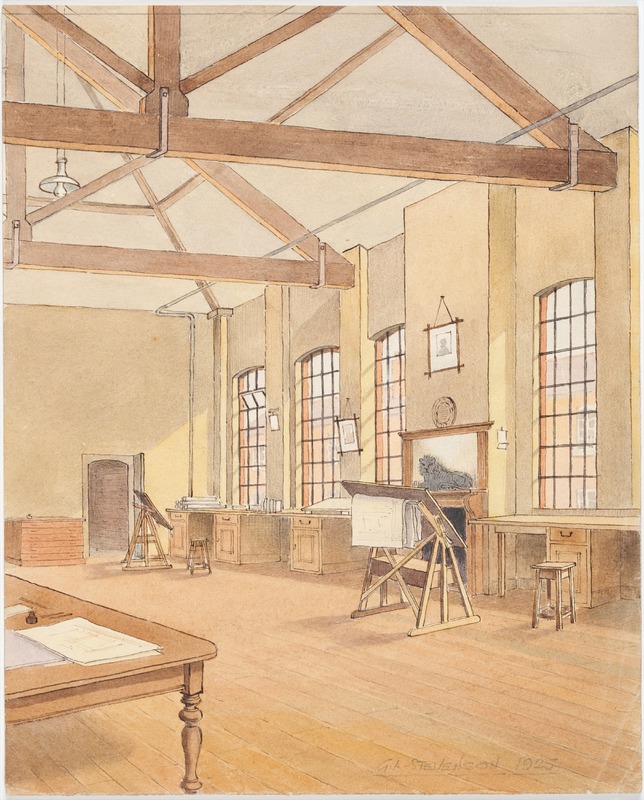

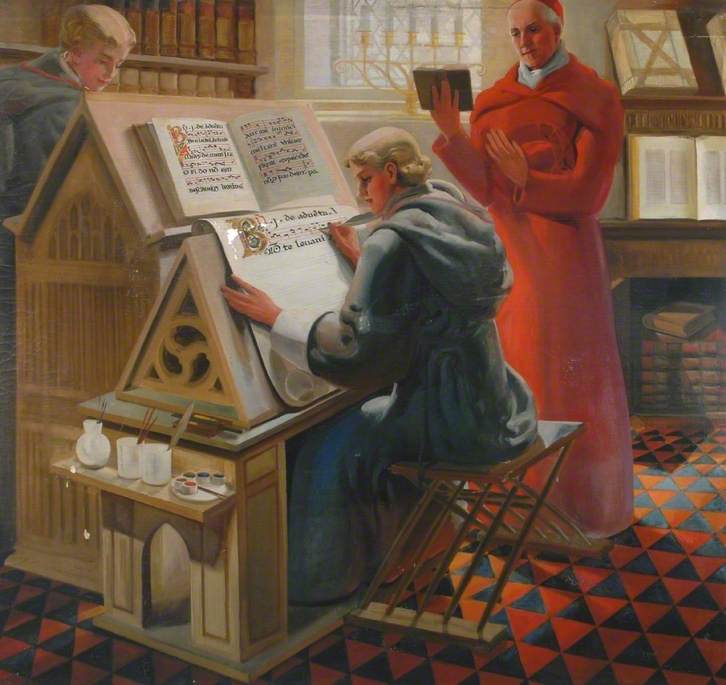

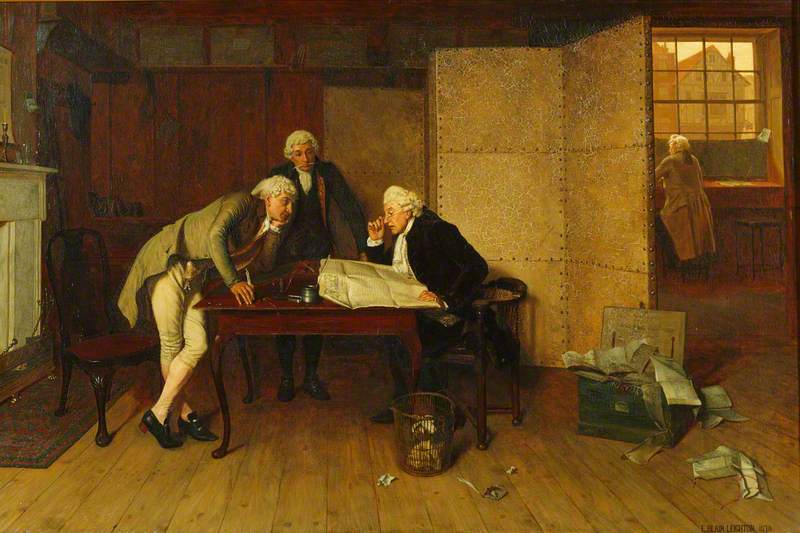

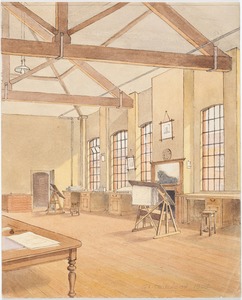

The office may seem like a modern invention, but it has existed since at least the fifteenth century when monks worked in small cubicles copying manuscripts in rooms called scriptoriums. But it wasn't until industrialisation in the eighteenth century brought vast amounts of paperwork that the office really came into its own. And, for almost as long, offices have had a bad rap.

How those fifteenth-century monks felt about their workspace is unknown but in the seventeenth century, essayist and office clerk Charles Lamb wished 'O for a few years between the grave and the desk!', while in the nineteenth century Charles Dickens described Bob Cratchit's desk in A Christmas Carol as 'a dismal little cell'.

Despite this apathy, there were almost one million office workers by 1911. And with the gradual decline of industry, combined with social and scientific progress in the twentieth century, we have witnessed the rise of the office as a central part of our working lives.

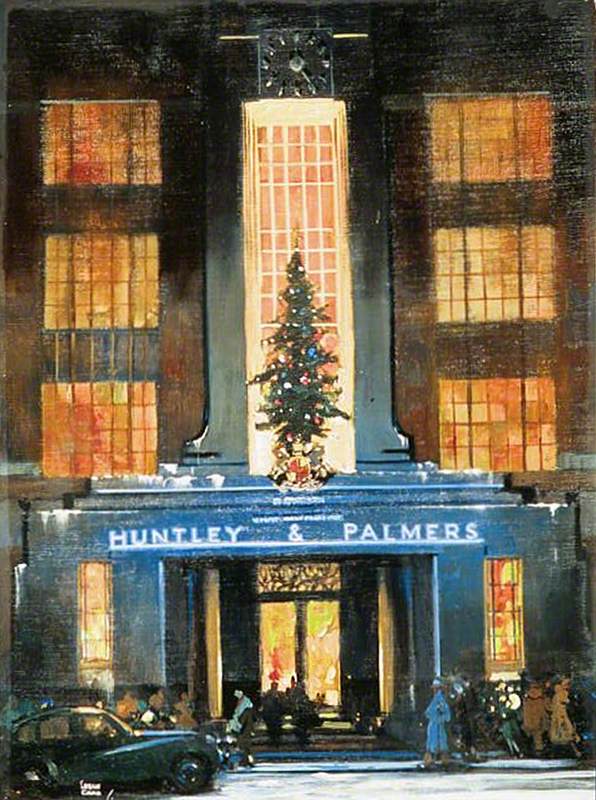

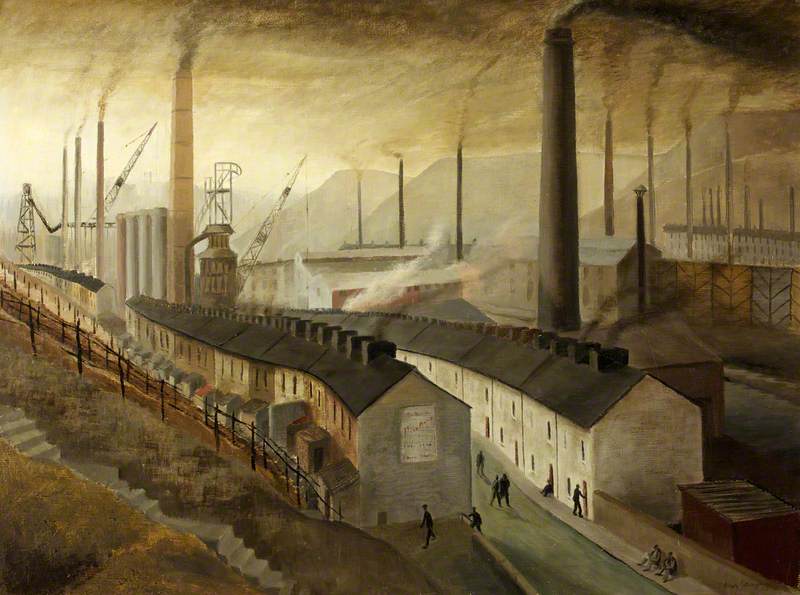

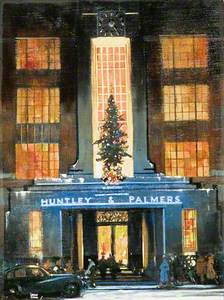

For the companies that built them, the office represented 'both a workplace and a visible statement of prestige and power'. This can be seen in early twentieth-century paintings, including Leslie Carr's Entrance of Huntley & Palmer's Office Building, which is painted at Christmastime in warm hues, suggesting homeliness while the decorations add to its prestige.

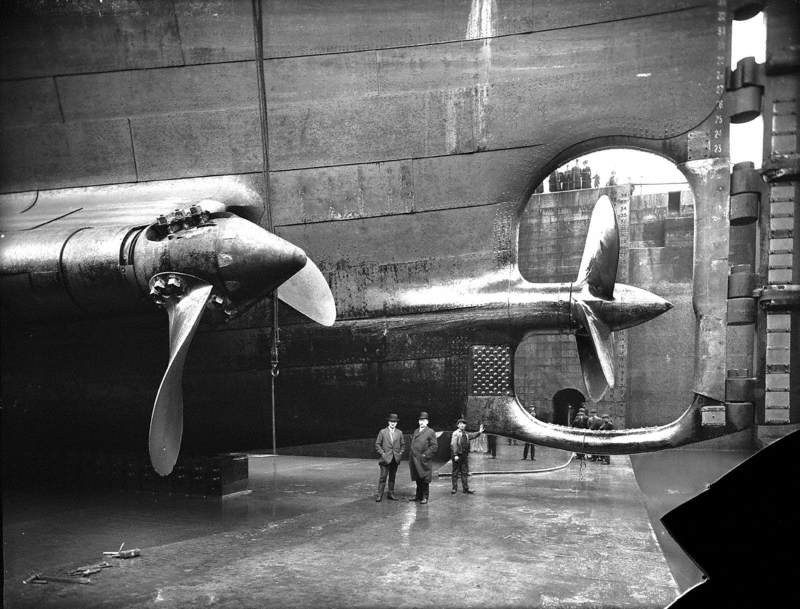

This contrasts with photographs of the Harland & Wolff offices. Taken by Robert John Welch, this series in black and white commemorates the building of new offices when the shipbuilder was working on the Titanic. The stark photos highlight their sturdy construction and imposing nature.

Image credit: National Museums NI

Front of new three storey extended main offices, Queen's Road c.1912

Robert John Welch (1859–1936) and Harland & Wolff (founded 1861)

National Museums NIThese artworks reflect the pride companies took in their offices at a time when the office building was changing. In 1902, the invention of the electric lift meant offices could grow up rather than sideways, and thus become grander and more imposing. London's first skyscraper with fifteen floors is believed to be 55 Broadway in Westminster, built in 1911.

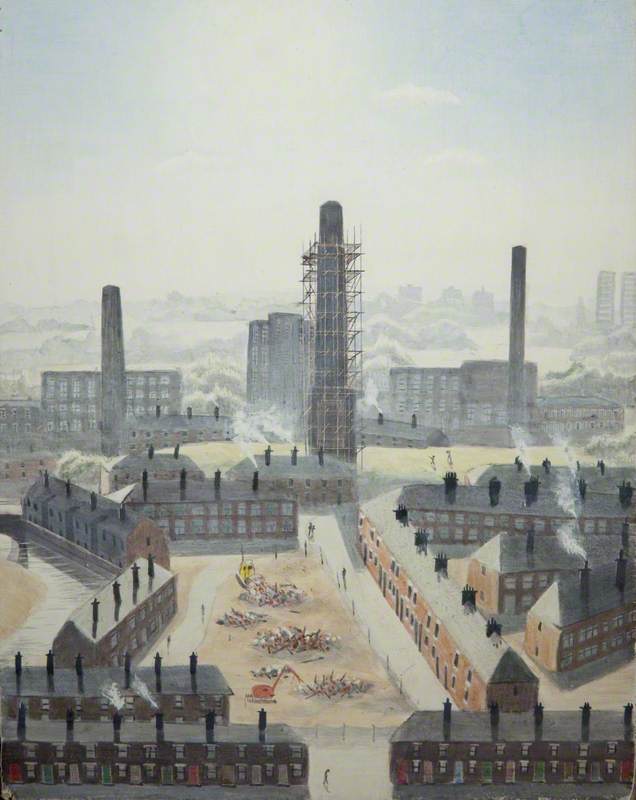

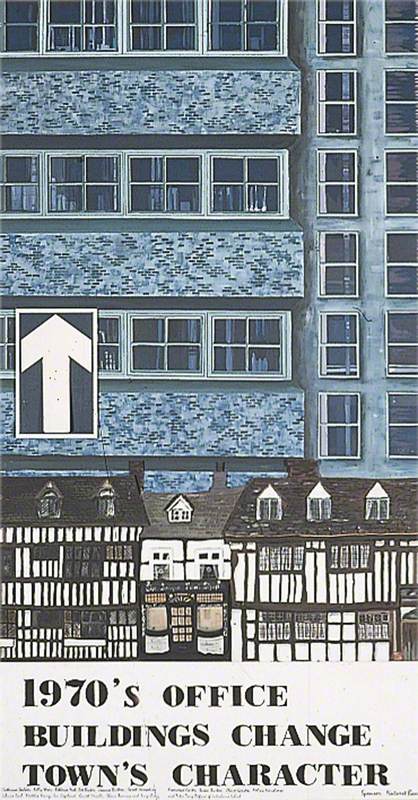

The growing importance of the office to our working life and to the economic life of the country meant that memorialising office buildings in art continued not simply for reasons of pride or prestige but for record keeping. This is seen in a work by East Grinstead Millennium Mural Team, which contrasts the medieval low-rises with the modern blue office towers that draw the eye away from the historic wooden-beam houses.

© the copyright holder. Image credit: Chequer Mead Theatre and Arts Centre Trust

1970s Office Buildings Change Town's Character 1999

East Grinstead Millennium Mural Team

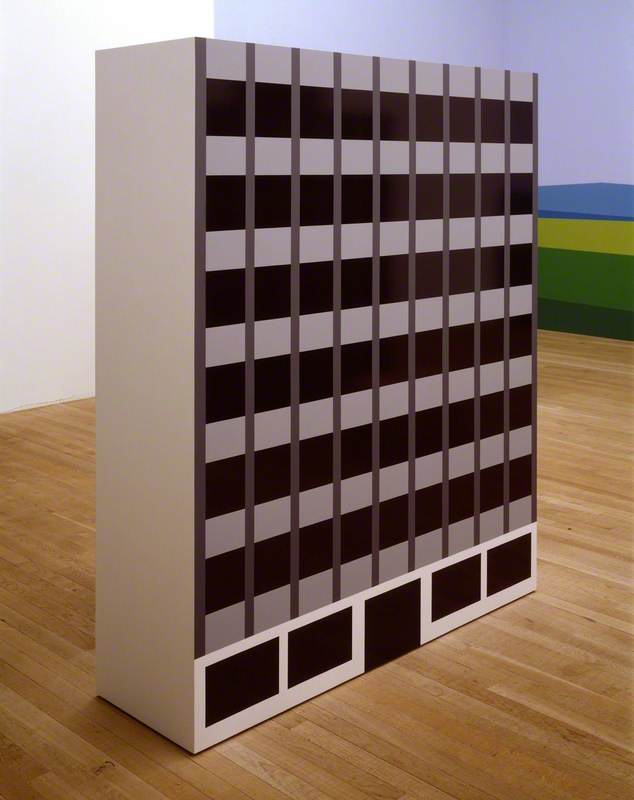

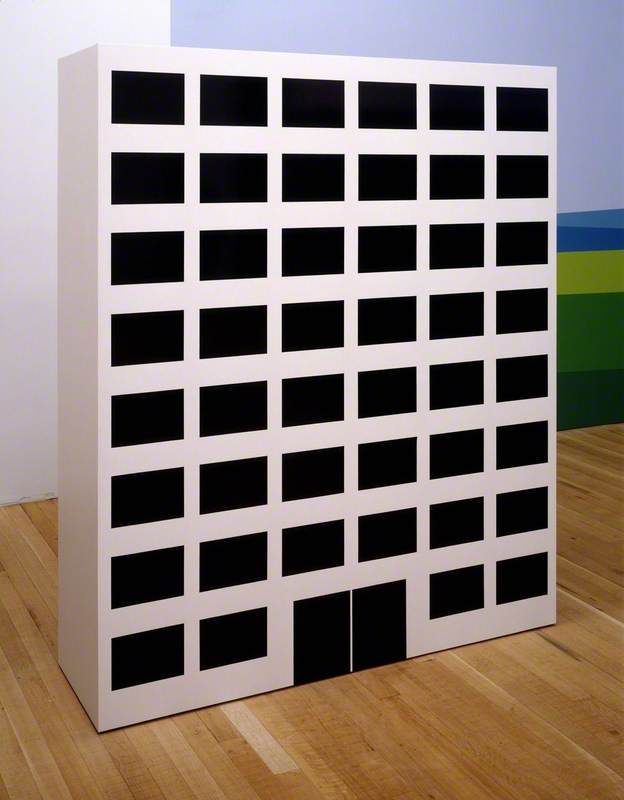

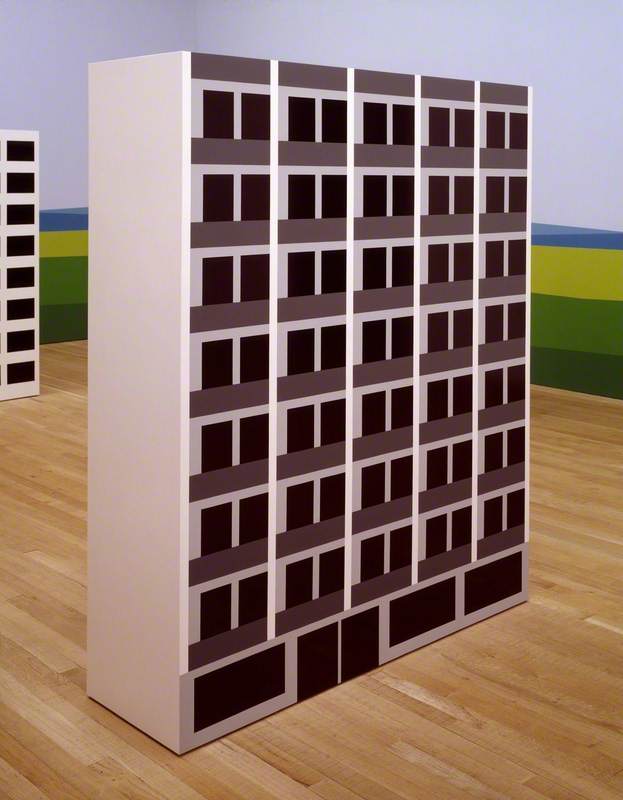

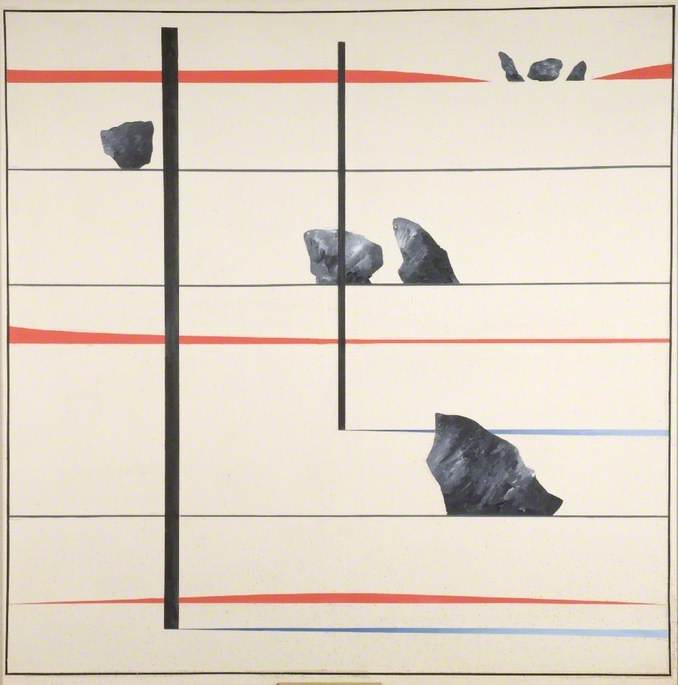

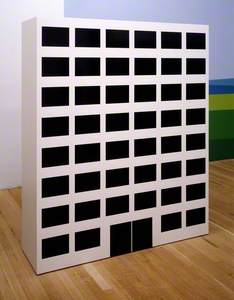

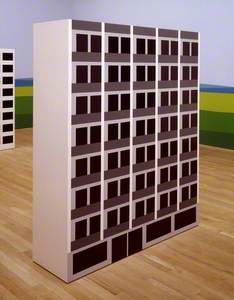

Chequer Mead Theatre and Arts Centre TrustIn the 1990s, Julian Opie's series of sculptures 'You see an office building' uses painted fibreboard and black and white paint to create hollow models with no identifiable features. They are representative of an office building but have no function or unique characteristic. In this way, they mirror the prevailing view of the office building as devoid of life.

This view was explored often in popular culture of the 1980s and 1990s. From films such as Terry Gilliam's Brazil, highlighting oppressive bureaucracy, and Mike Judge's Office Space, which skewered office relationships, to Chandler Bing's meaningless job in the sitcom Friends, they lampooned the routine of office life and reflected a broader cultural view of offices as dull and bureaucratic.

But where television and film sought to ridicule – perhaps to most spectacular effect in British mockumentary The Office – art attempted to laugh at and enliven the office spaces so many of us inhabit.

Adam Reynolds' Graduate Training, for example, both mocks the world of the office and invites the building and its workers to laugh too by placing its depiction of two trainees scaling an office block in situ. It allows the very space it is laughing at to be in on the joke.

Another way art subverts our expectations of office spaces is through colour. In this mural, a collaboration between Paul 'Monsters' Roberts and SNUB23, the typically grey walls of an office building become a canvas, the artists managing to enrich the space and challenge ideas around what an office should look like.

© the copyright holders. Image credit: Tracy Jenkins / Art UK

Paul 'Monsters' Roberts (active since 2011) and SNUB23

High Street, Southend-on-Sea, EssexSimilarly, Jun. T. Lai's Bloom Paradise uses colour to bring an absurdist warmth to the outside space of an office. The rounded edges and vividly coloured petals of Lai's flowers brighten the space and again it works because of the blank canvas of the walls and plazas of the office building.

Both artworks were commissioned by the cities themselves to add character to grey, concrete environments that proliferated in the post-war years. Often filled in with brutalist architecture of the 1960s and 1970s or by modern glass and steel skyscrapers, it is these very features which offer artists a canvas on which to ridicule, breathe life into and offer an identity to an otherwise blank page.

Art has also moved inside the revolving doors to depict the utilitarian objects within offices. Opie's H replicates an air vent, a functional office item that nevertheless loses its functionality in Opie's model. Yet we are forced to consider it now that it has been taken out of context and placed before us.

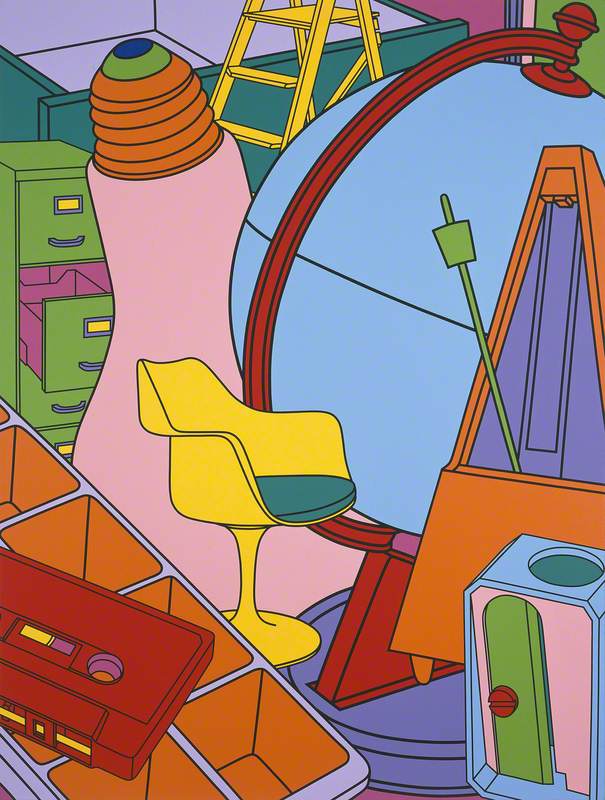

Similarly, Paul Robert Charles Stevenson's Prototype Duo and Michael Craig-Martin's Inhale (Yellow) go to similar lengths to highlight the object, to bring the unnoticed into full view so that we think about our relationship with it and with the mundane.

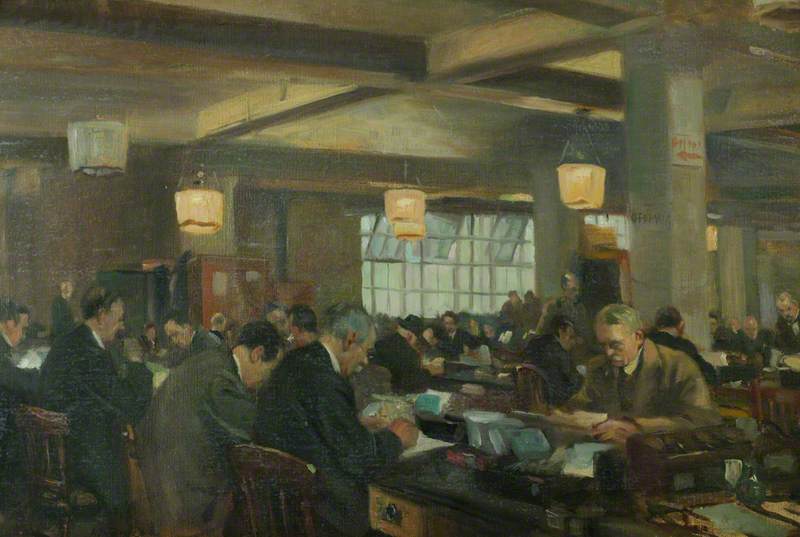

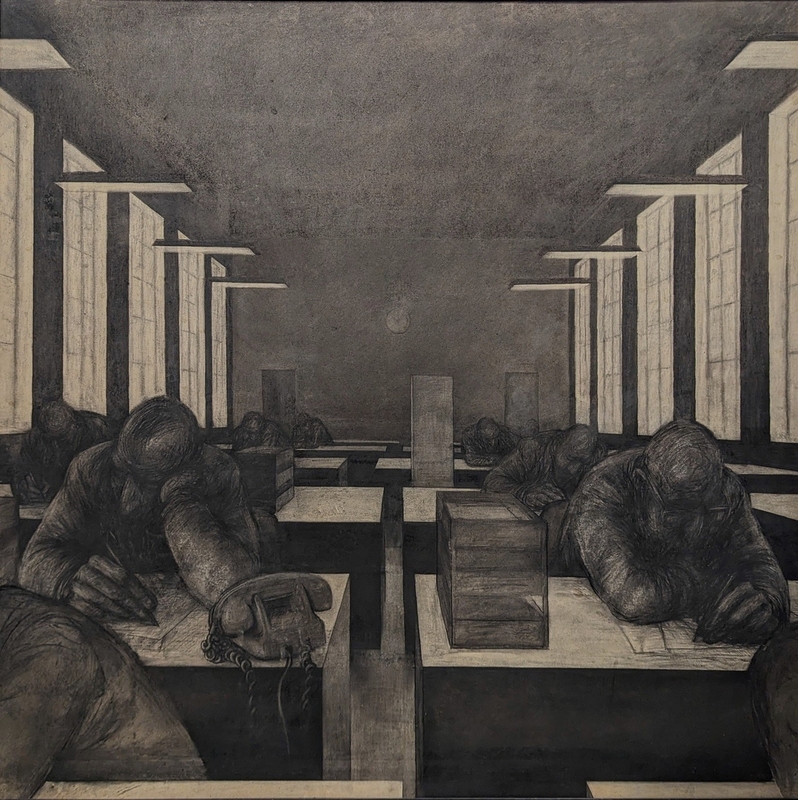

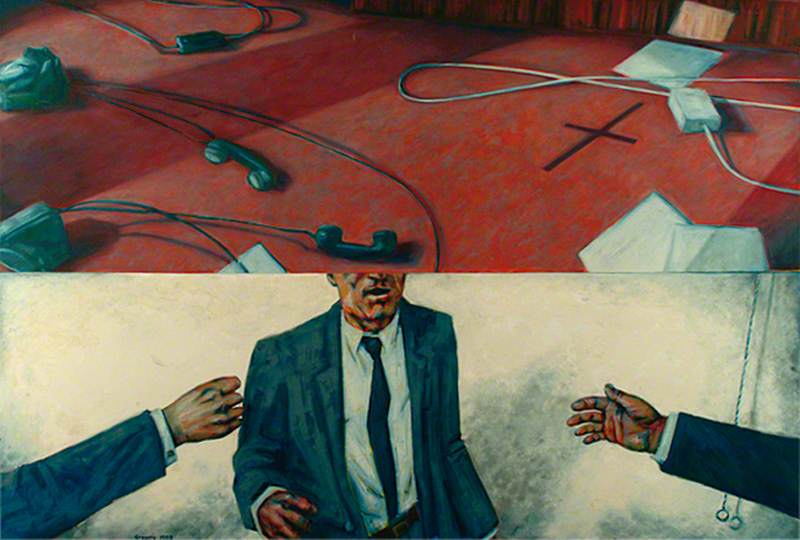

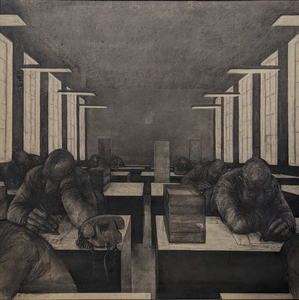

This mundanity is also seen in depictions of people who work in offices: the uniform of the dark suit and tie, the omnipresent desk and the overwhelmingly white male workers that populate the spaces. In both Frances Watt's Interior of Lloyd's from 1963 and Patricia Gregory's 1989 The Meeting we are presented with very similar portrayals of the office worker: white, male and besuited.

In the more than a quarter of a century that separates the two paintings, there was much social change, yet the people within offices remain the same.

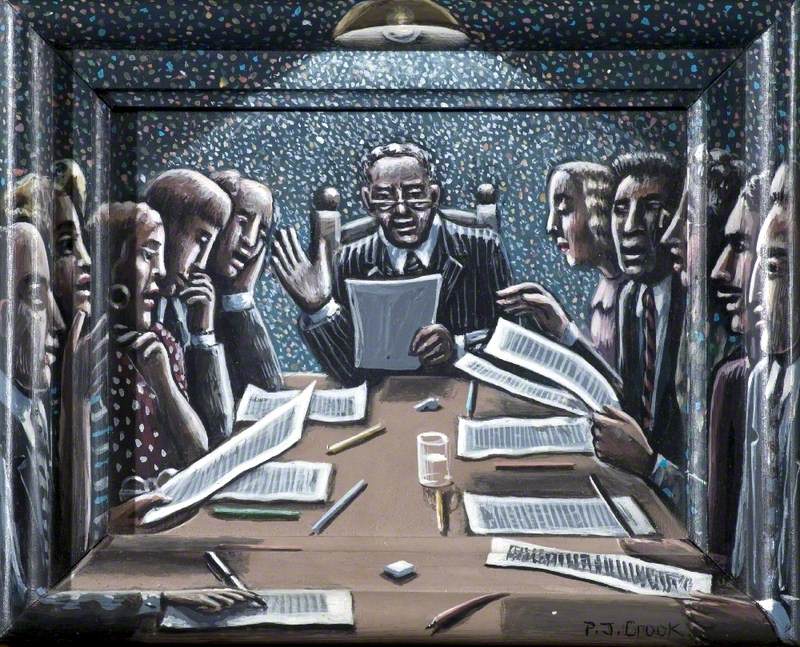

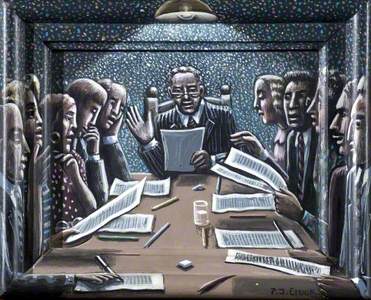

In P. J. Crook's Staff Meeting from 1990 we see the inclusion of women. They bring with them a change of attire, but conformity still exists in the men's suits and the familiar objects. The women remain outnumbered, and it is still a white man that leads the meeting.

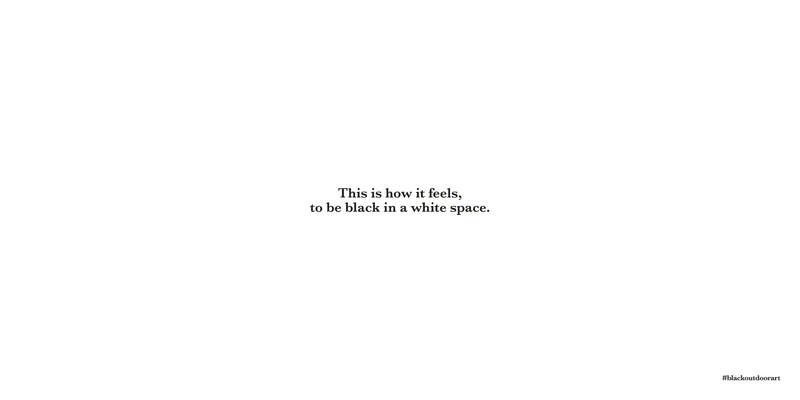

Greg Bunbury's White Space uses the starkness of black and white, but unlike Welch's photographs displaying the pride of the shipbuilder's offices, Bunbury uses colour to challenge the lack of diversity in the workplace.

Where once art was used to depict pride in ownership, it is now used to challenge the ownership of office spaces, the dominance of whiteness in those spaces and the lack of people of colour, as reflected in the small black type within a large white space.

Since the pandemic, we have seen perhaps the greatest challenge to the office's place in our lives: the work from home revolution which has led to increasing numbers of workers creating home offices, allowing for greater flexibility and non-conformity.

But with office blocks left empty and people preferring hybrid working, the office is facing a reckoning. As Apple TV's Severance reignites conversations about office life and large corporations are demanding a full return to the office, we are also recognising the downsides of home working, including isolation and a lack of work-life balance.

As such, it's yet to be seen whether this is the end of the traditional office or the start of a renewed appreciation of office life with all its familiar settings, routines and relationships.

Lorna Lee, writer

This content was supported by Jerwood Foundation