Until recently, the history of Black mariners and service people in the UK has been largely unheard. This is due to a wider lack of awareness of the Black presence in British history prior to 1948.

The exhibition 'Black Greenwich Pensioners' at the Old Royal Naval College, Greenwich from 3rd October 2020 to 21st February 2021, aims to uncover the history of Black mariners who were in the Royal Navy in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, bringing awareness to their lives and varying fascinating stories, from contributing to abolitionist literature, to escaping enslavement, to serving at the Battle of Trafalgar.

A Caricature of Greenwich Pensioners

c. 1800, pen & brown ink with watercolour over pencil by John Thurston (1774–1822)

Before it was the Old Royal Naval College, the site was the Royal Hospital for Seamen, where those who had served in the Royal Navy, and who were deemed injured or infirm, resided as pensioners. They were a significant part of the local Greenwich community.

The Old Royal Naval College has spent over 10 years delving into their records of these Greenwich Pensioners, looking particularly at the history of Black people at the Royal Hospital of Seamen. The resulting exhibition, 'Black Greenwich Pensioners', explores the stories of Black mariners who became Greenwich Pensioners.

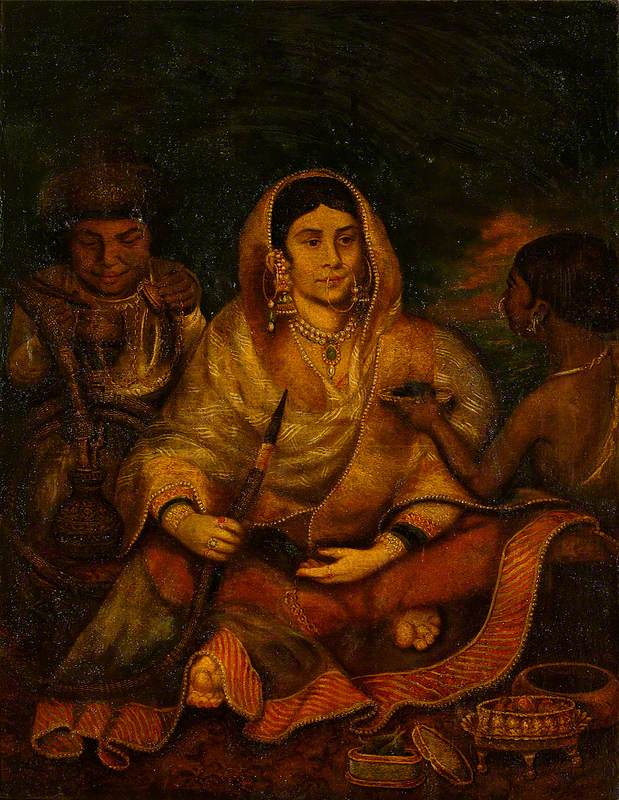

The exhibition shows the breadth of backgrounds that seamen had, from a pub landlord to a Trafalgar veteran and an enslaved man. It also highlights the remarkable variety of roles that Black seamen had in the Royal Navy. Britain's navy was the largest in the world in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and to maintain their maritime dominance, they drew personnel from across the globe, not just the British Isles.

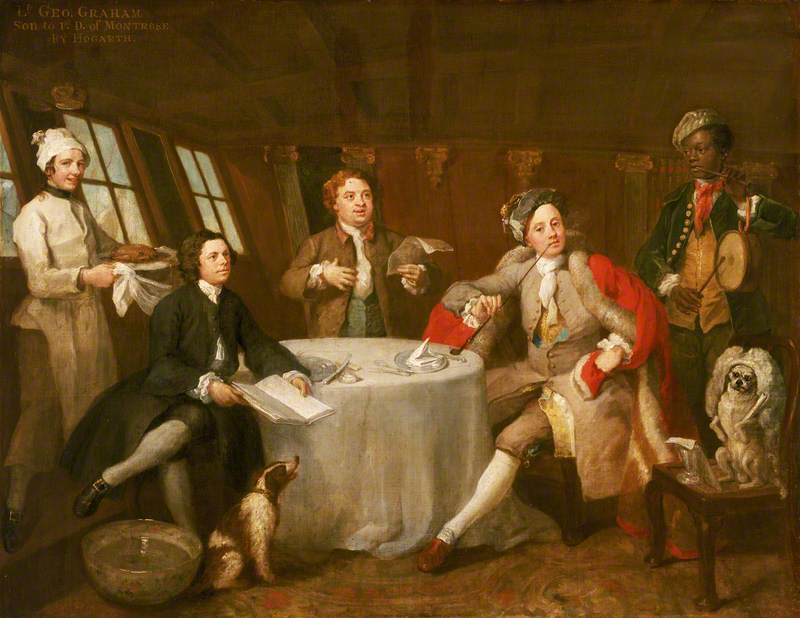

They employed Black men, free and enslaved, from the Americas, the Caribbean, Africa and Britain. Black mariners played every possible role at every level of the Navy during conflicts in the eighteenth century, from cook to quartermaster to, in one known case, ship's captain (Captain John Perkins).

The Death of Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar, 21 October 1805

c.1806

Samuel Drummond (1765–1844)

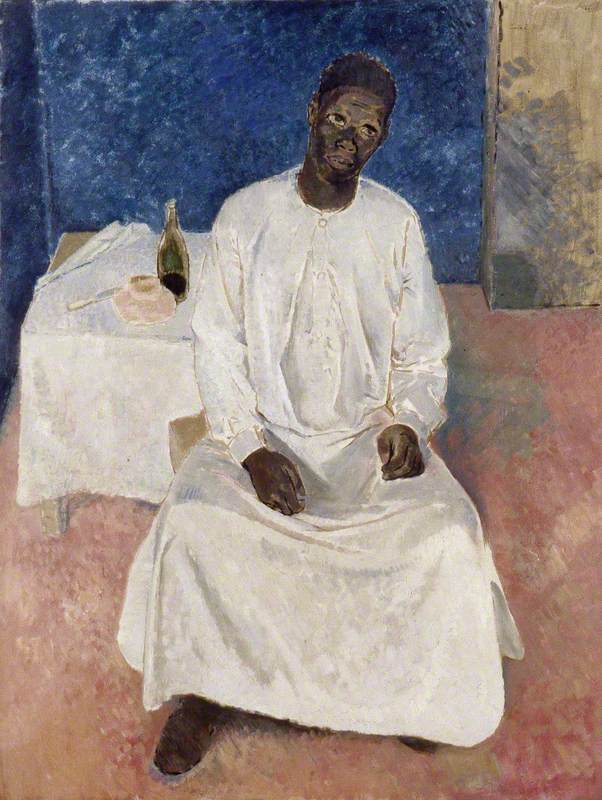

Frederick Zeegular was understood to have served in the Dutch army prior to his arrival in Britain. By 1808 he was the landlord of the Cock and Lion pub in Wigmore Street and had married a British woman. He became a Freemason, causing controversy and an investigation into the 'entering and crafting a Black person' at his Lodge, until 1821 when he joined the Royal Navy. He later became an in-pensioner of the Royal Hospital for Seamen.

John Thomas was born into slavery on the Newton plantation, Barbados. In 1808 he alleged cruelty by the plantation manager and ran away to sea, leaving behind his family and joining the Royal Navy. In 1815 he was discharged from the Navy with a Greenwich pension and returned to enslavement in Barbados. Before his return, he stated his grievances to the Newton plantation landlord in London, and asked to be sent home with the promise of no 'stripes' (lashes). By 1830 he was owed £56 of a pension he couldn't be paid. The Admiralty reportedly wondered 'how this man can now be a slave having once been in His Majesty's Service?'.

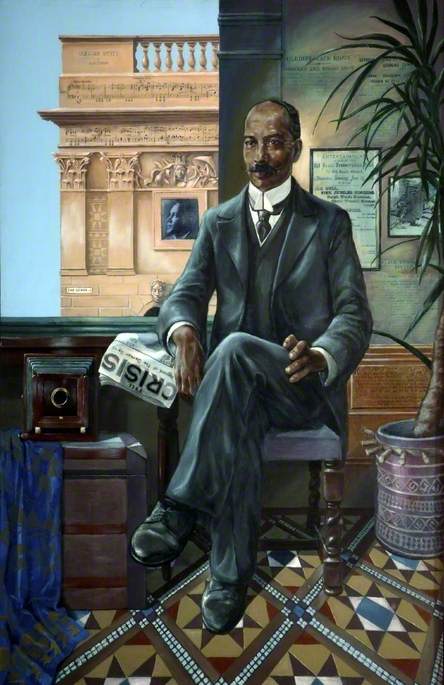

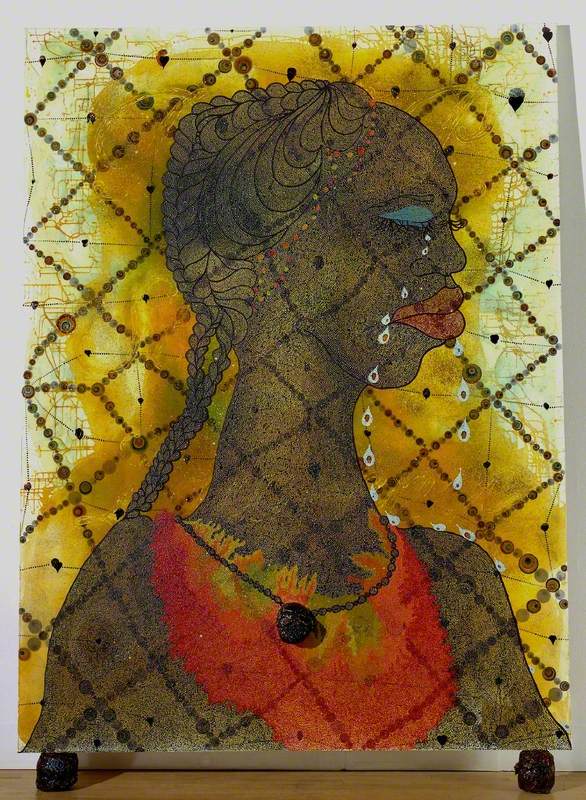

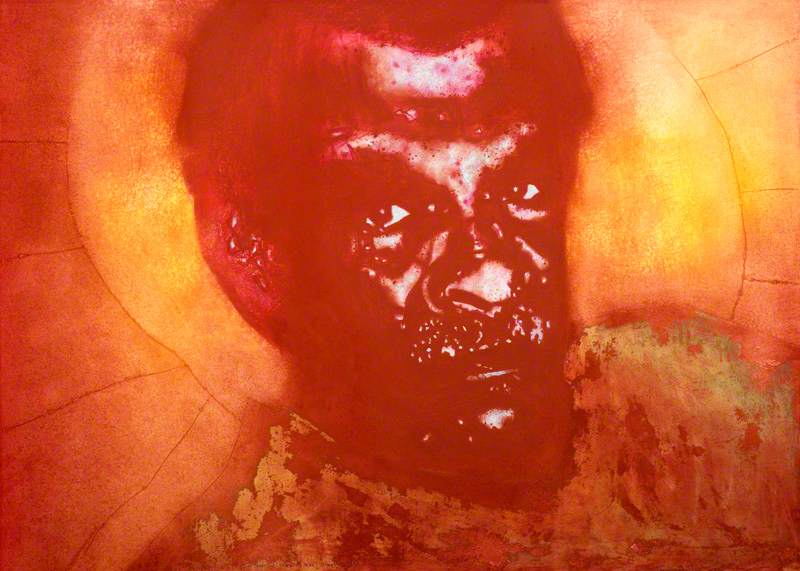

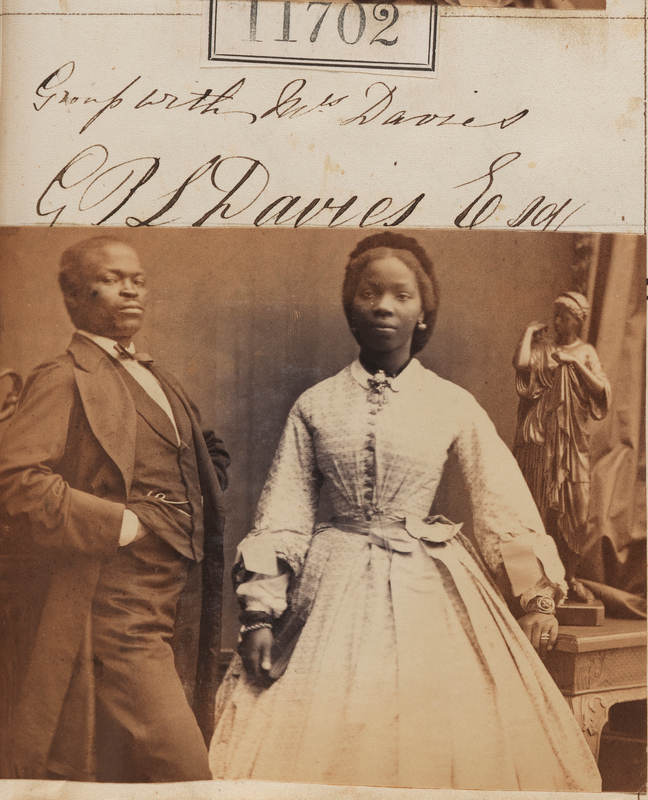

We have brought together a number of fascinating letters, photographs, paintings and prints in the exhibition to tell the stories of the Black mariners, including portraits, newspaper cartoons and more. Many of these show Black Pensioners in their Naval uniforms and medals, in the company of white mariners.

Andrew Morton's 1845 painting The United Service, for example, shows Black Pensioner John Deman, who appears in a red hat, as part of a welcome committee of Greenwich Pensioners for visiting red-coated Chelsea Pensioners. The group can be seen looking at a painting of Admiral Lord Nelson's victory at the Battle of the Nile. The nine Greenwich Pensioners all served under Nelson. Deman, born in Nevis around 1774, had joined the Royal Navy as a young boy and served with Nelson. He arrived in Britain in the 1790s, serving on Nelson's ship the Boreas.

The Battle of the Nile, Greenwich Pensioners Disputing the Line of Battle

1827, mezzotint by William C. Giller, based on an original painting by Henry James Pidding (1797–1864)

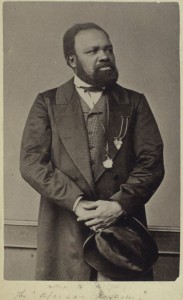

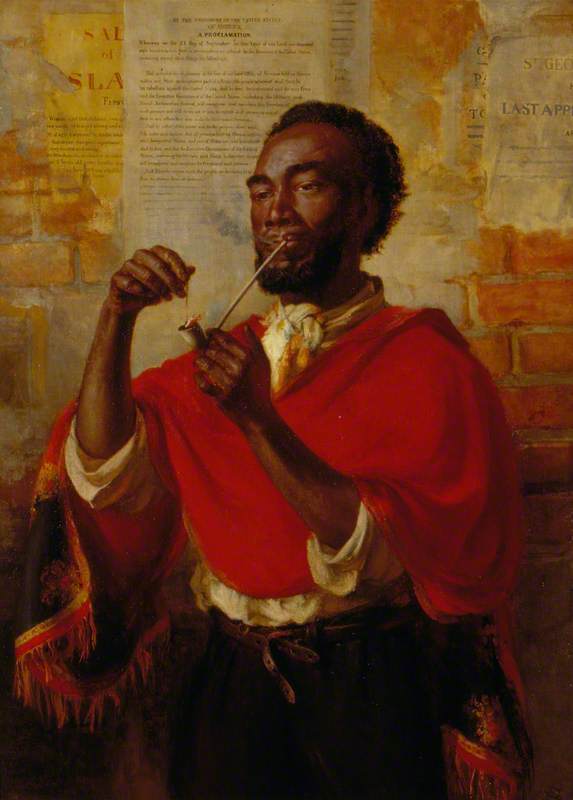

Also featured in the exhibition is a fascinating portrait of Black Greenwich Pensioner John Simmonds. Simmonds had the portrait made in Mansfield Market after receiving the Trafalgar Medal in 1848. He can be seen in his naval uniform wearing his medal, a replica of which is on display in the exhibition, kindly lent by Simmonds' descendants. Simmonds was born in Jamaica in the 1780s, possibly the son of a white plantation owner and his Black enslaved housekeeper.

In 1803, Simmonds was pressed into service on the HMS Révolutionnaire, a common practice where men were forced into service in the Royal Navy to strengthen their numbers. Simmonds transferred to the HMS Conqueror, which famously accepted the surrender of the French Admiral Villeneuve at the Battle of Trafalgar, on 21st October 1805. Later, Simmonds advanced to the role of quartermaster on the HMS Variable. He became an in-pensioner at Greenwich in 1824, before marrying a white Londoner and moving to Mansfield until his death in 1858.

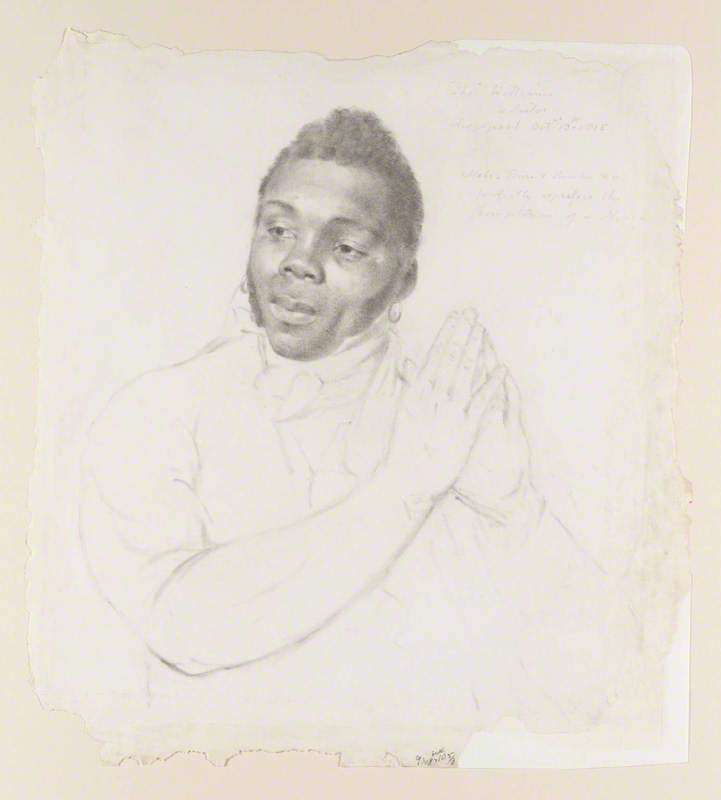

John Simmonds (c.1784–1858), Veteran of the Battle of Trafalgar and Black Greenwich Pensioner

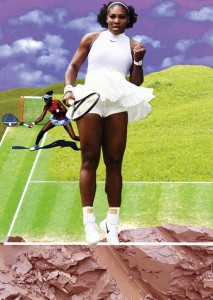

These are just a few examples of the incredible lives led by Black mariners in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, showing the range of backgrounds and roles held in the Navy by this now often overlooked historical Black maritime community. The exhibition also shows the breadth of the Black Greenwich and Deptford communities, which first emerged as far back as the 1500s.

It is great to see heritage institutions begin to engage with their diverse histories. It is so important that these stories are told, as it gives us a more comprehensive view of military history, British history, and the history of enslavement.

I hope that visitors to 'Black Greenwich Pensioners' will come away with a sense of how local histories are connected to global histories, and that Black histories are everywhere.

S. I. Martin, author, historian, journalist and curator of 'Black Greenwich Pensioners'

'Black Greenwich Pensioners' is at the Old Royal Naval College, Greenwich from 3rd October 2020 until 21st February 2021