2nd November 2019 marked the thirtieth anniversary of the broadcast of one of the most moving endings of a TV series ever – the final memorable episode of Blackadder Goes Forth. Even today, watching the episode and its stark ending has an emotional impact. An ending best watched rather than described.

In the very first episode of the fourth series (Captain Cook, first broadcast 28th September 1989), Blackadder becomes an artist, believing that this is his chance to escape the trenches. However, it is revealed that the artist is actually to undertake a highly dangerous job – to draw the enemy's defences from No Man's Land. This episode echoes the work undertaken by the men of the Artists Rifles – a regiment with one of the highest casualty rates of the First World War.

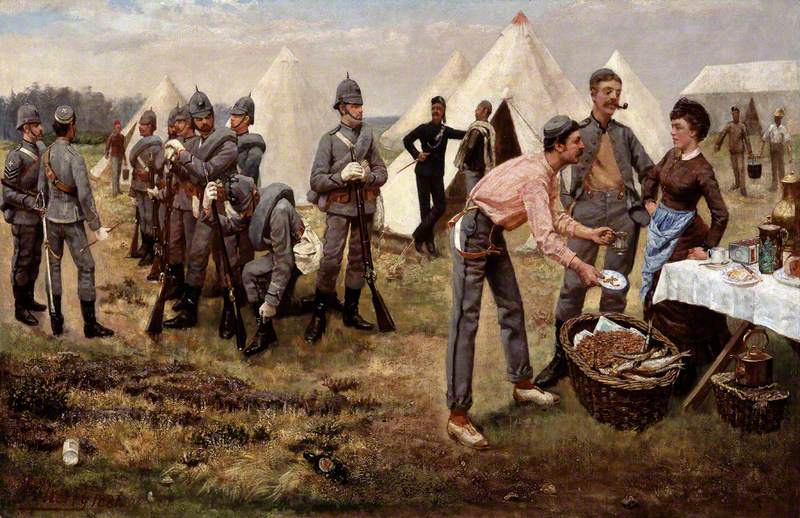

The Artists Rifles regiment was formed in 1859 by art student Edward Starling. It was a volunteer regiment and formed out of the widespread fear of a French invasion. Many of those who joined were artists, actors, musicians and architects and its first headquarters was located at Burlington House. Its first commanders were the painters Henry Wyndham Phillips and Frederic Leighton.

Creativity and beauty were at the core of the Artists Rifles. This may seem an odd combination for an army regiment but one can see both qualities even in the regimental cap badge.

The regimental cap badge of the Artists Rifles

designed by Leonard Charles Wyon (1826–1891)

This was designed by Leonard Charles Wyon, an engraver at the Royal Mint, and features the heads of the Roman god Mars and the goddess Minerva – war and wisdom.

Other great artists also joined the regiment in its early period, such as John Everett Millais, G. F. Watts and William Morris. Looking at this list one could easily dismiss the regiment as a 'club', an excuse for a 'jolly', but the Artists Rifles were a fighting, active regiment and saw action in the Boer War. After some reorganisation it became the 28th (County of London) Battalion on 1st April 1908.

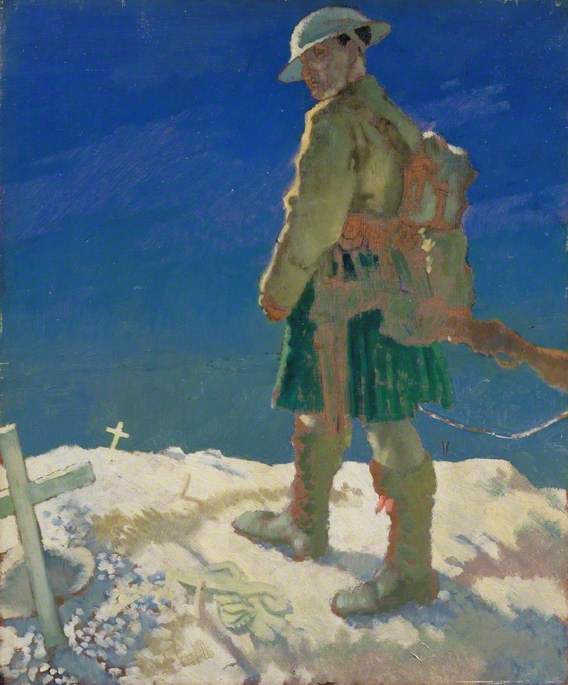

The First World War would see the regiment literally leading from the front as they become a training regiment for officers in this period. It is also for this reason that the Artists Rifles had one of the highest casualty rates of any regiment.

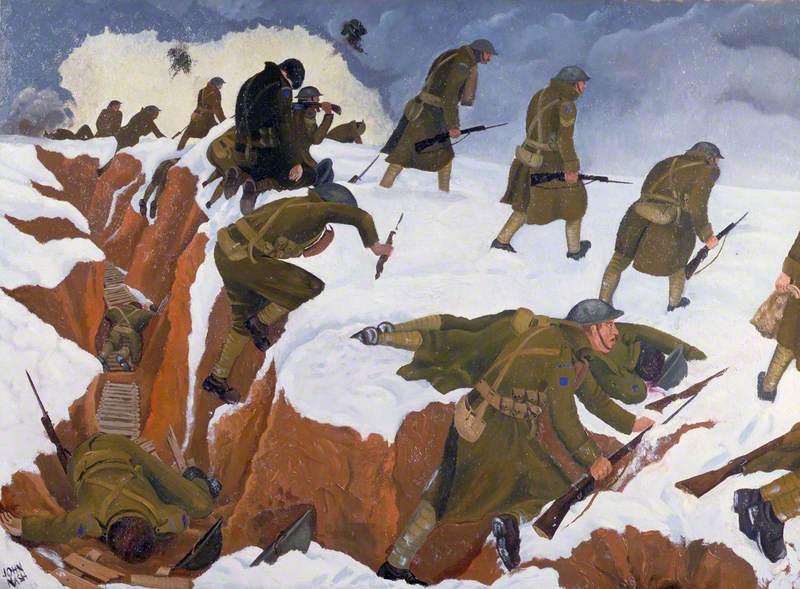

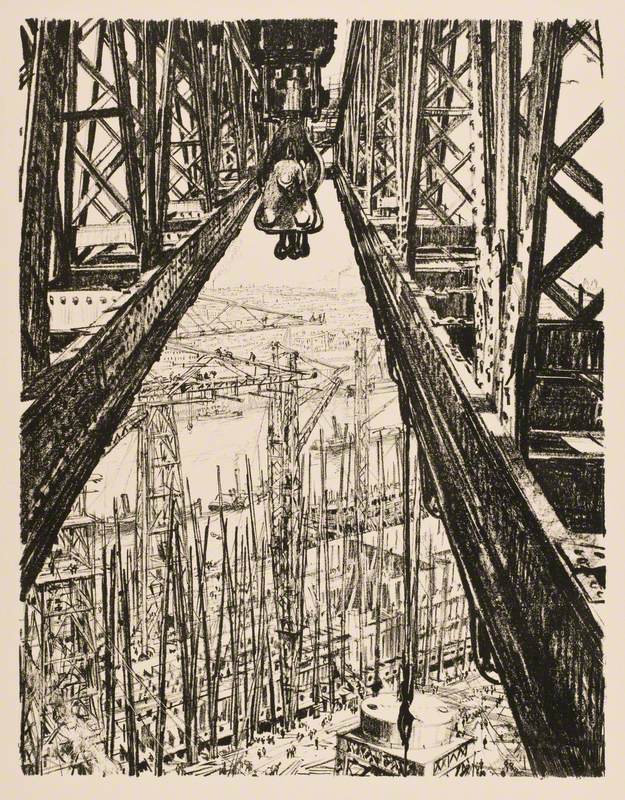

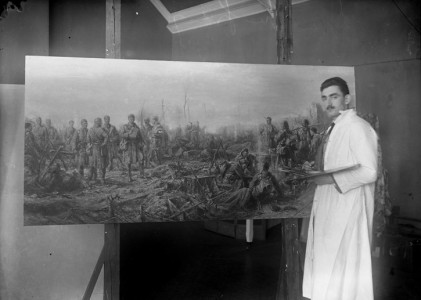

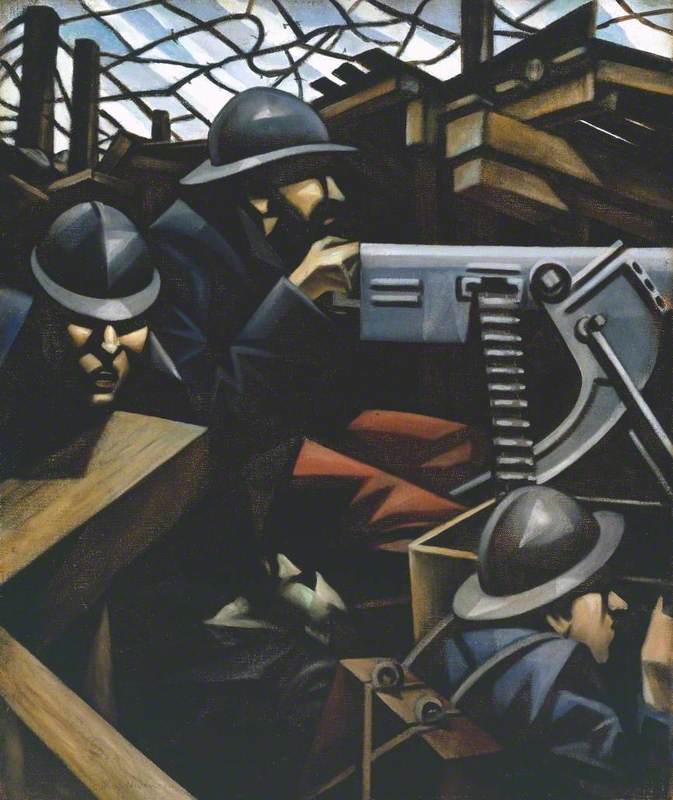

'Over The Top': First Artists Rifles at Marcoing, 30 December 1917

1918

John Northcote Nash (1893–1977)

The painting Over the Top by John Nash depicts his regiment in action. On 30th December 1917, the 1st Artists Rifles counter-attacked at Welsh Ridge, south-west of Cambrai. Nash called the action 'pure murder' as most of the company were killed. John Nash, a sergeant, counted himself lucky to escape the carnage.

Some of the great artists of the twentieth century saw action with the regiment in the First World War. This experience had an impact on their work and created some of the most iconic art to emerge from the conflict.

Others who served included John's brother Paul Nash, Charles Jagger and Barnes Wallis (who would go on to invent the 'bouncing bomb' of Dambusters fame).

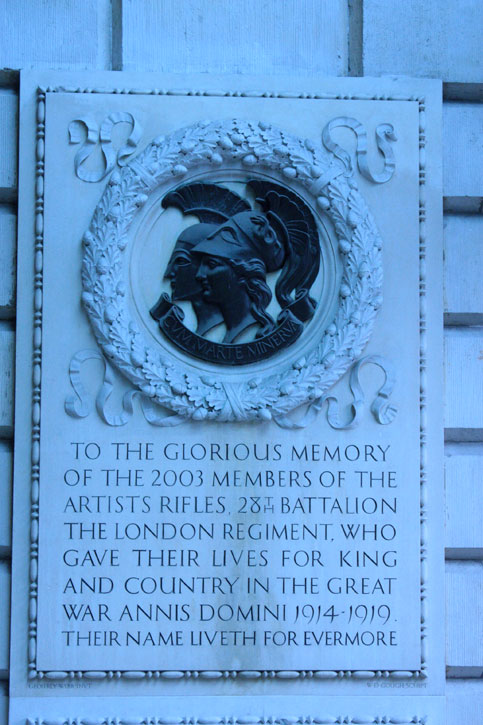

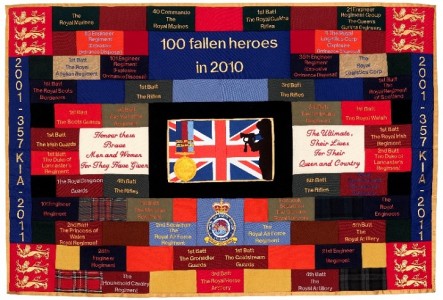

During the Great War, 2,003 of the regiment's men were killed and over 3,000 wounded. Members of the regiment would be awarded eight Victoria Crosses and over 850 other military awards including the Distinguished Service Order (awarded 52 times) and the Military Cross (awarded 822 times). They were also mentioned 564 times in dispatches.

One can only imagine what the art world would have lost if these men had been killed while serving in the front line. Perhaps this loss can be glimpsed through the work of poet Edward Thomas, a master of observation who was killed in 1917. Thomas started writing poetry at the age of 36 in December 1914. He enlisted in the Artists Rifles in July 1915. He was commissioned in November 1916 into the Royal Garrison Artillery as a second lieutenant and soon volunteered for active service.

One of his most famous poems is Adlestrop about a Gloucestershire railway station on a still afternoon. Written in January 1915, as war rages overseas Thomas captures the uncapturable stillness of the moment. In April 1916 he wrote a poem inspired by his six-year-old daughter. Here is an excerpt:

What shall I give my daughter the younger

More than will keep her cold and hunger?

I shall not give her anything.

If she shared South Weald and Havering,

Their acres, the two brooks running between,

Paine's Brook and Weald Brook,

With pewit, woodpecker, swan and rook,

She would be no richer then the queen.

Thomas illustrates the intangible beauty of the countryside in words and transfers this to our mind's eye. A year after writing this poem he was killed taking part in the Battle of Arras. He was dead within the first hour of the engagement on Easter Monday, 9th April 1917.

One wonders what this man would have achieved if he had survived, as can, of course, be said about all those who die in conflict.

After the horrors of the First World War, the Artists Rifles were active as a training regiment in the Second World War, had links with the Special Air Service and become a unit of the Territorial Army in 1967.

A memorial to the men of the Artists Rifles can be viewed at Burlington House.

Memorial to the Artists Rifles in Burlington House

Perhaps next time you visit the Royal Academy go and seek this out and pause for a moment.

Gary Haines, archivist and researcher

.jpg)