While he is best known nowadays for nonsense poetry, most indelibly The Owl and The Pussycat, during the nineteenth century Edward Lear (1812–1888) made the bulk of his living as a landscape painter. He devised a style the artist himself described as 'poetical-typographical', imbued with a stillness and serenity at odds with his often-manic illustrated rhymes.

An exhibition at Birmingham's Ikon Gallery, 'Edward Lear: Moment to Moment' brings together almost 60 works by Lear, revealing his compulsive desire to travel and experiment with methods of composition.

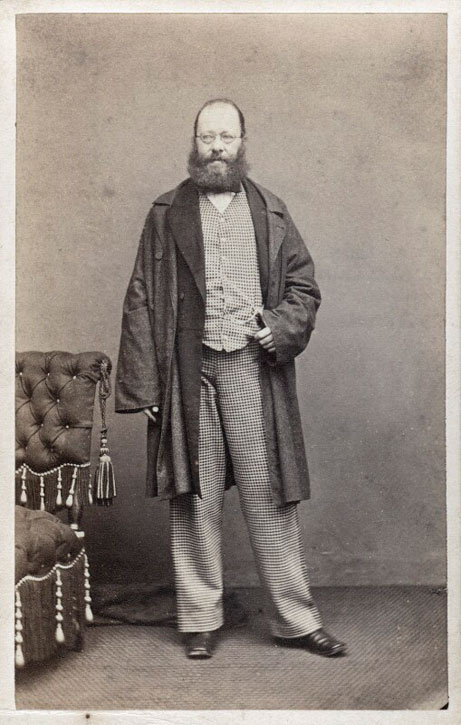

Edward Lear

1862, albumen carte-de-visite by McLean, Melhuish & Haes (active 1861–1863)

From the 1840s onwards, this prolific poet did much to popularise limericks as a comic form, though by then he had already made his name as a skilled draughtsman. Indeed, Lear became known as one of the most intrepid artist-travellers of the Victorian era. Over a 50-year career, he ventured across Europe and the Middle East to India and his illustrated travel books sold well enough to support his peripatetic existence.

Red-capped Parrot – 'Platycercus pileatus. Red-capped parrakeet'

1830?, illustration by Edward Lear (1812–1888)

Largely self-taught, he started out drawing birds and animals for the Zoological Society, forging a long-standing relationship with the famed menagerie at Knowsley Hall, near Liverpool. The owner, the Earl of Derby and his descendants, were among the first of several high-placed and influential patrons. Aged 18, Lear published his first book: Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots (1830).

He only turned to topographical painting later that decade when such detailed work started to affect his eyesight. This was just one of Lear's health problems, alongside epilepsy, a condition that at the time carried a great deal of social stigma, leading to or exacerbating his tendency to shyness and depression.

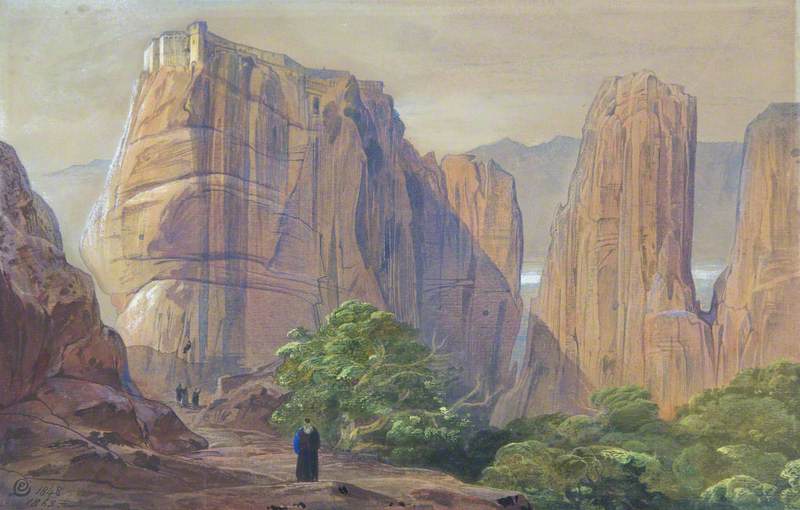

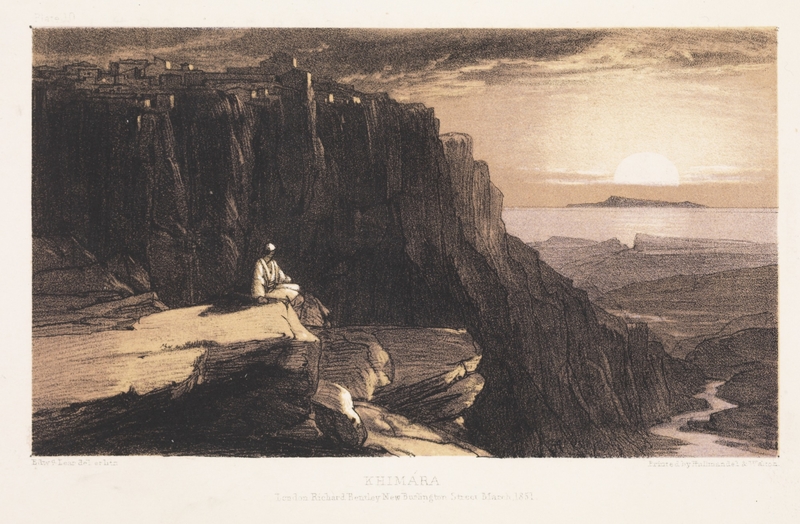

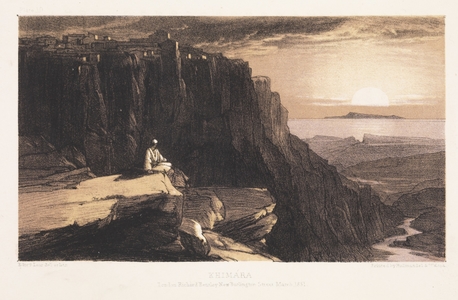

Lear's travels began with trips to Ireland and the Lake District in northwest England, though he soon sought the warmer climate of southern Europe to ameliorate his ill health and depressive nature, avoiding also the constrictions of mainstream society. From 1837 to 1848, Lear was based in Italy before travelling to Greece. He was drawn to locations with historical significance, such as Thermopylae, the site of a famous battle in 480 BC between the Spartans and a much larger Persian force.

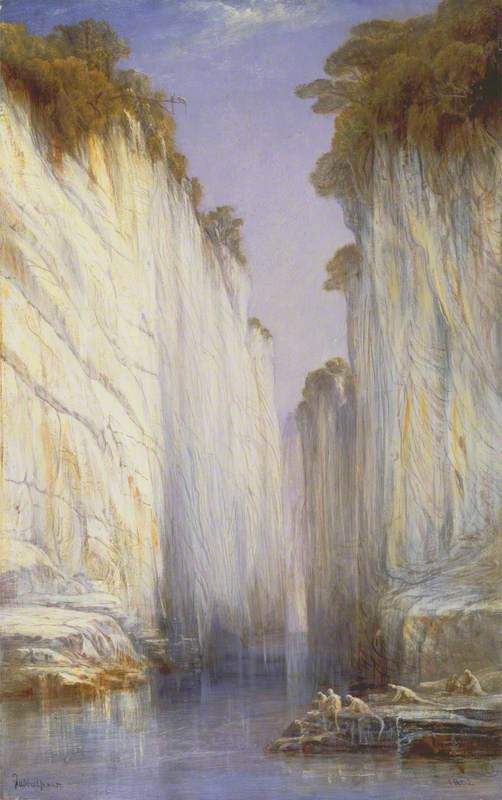

He began working in watercolours, the foundation of the artist's clear and well-lit style with painstaking attention applied to geographical accuracy and observational detail, often finishing works years after he made his original sketches. Rather than aiming for a naturalistic appearance, Lear carefully staged his scenes to enhance the picturesque, placing natives in the foreground, whether Greek goatherds or Tibetan figures at a Buddhist shrine.

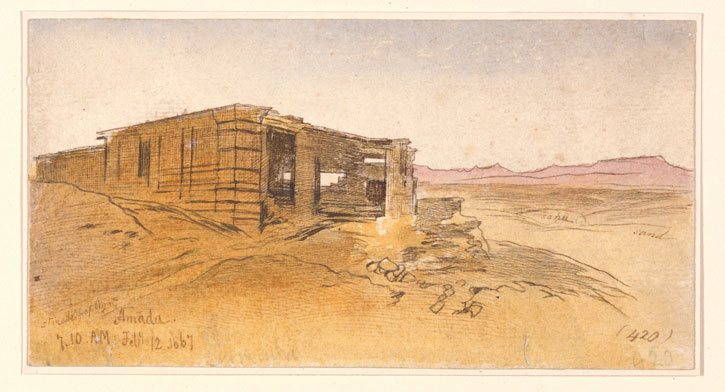

Lear regularly numbered his sketches, noting not only the date and location but the exact time of day, alongside sensory observations and more whimsical thoughts. In February 1867, for example, the artist created five successive drawings of the Amada temple in Egypt, between 6.50am and 7.30am (his favourite time to work was around daybreak). Each image differed slightly in perspective and foreground figures, some accentuating the dilapidated structure, while others the surrounding landscape.

Amada

1867, pencil, pen & ink with wash on paper by Edward Lear (1812–1888)

Such drawings form the basis for the exhibition at Ikon Gallery, which examines his works in detail for clues as to Lear's creativity. Matthew Bevis, consultant curator for the show, believes they are far more than references or trials for future work. In the exhibition catalogue, he writes that they were 'a way for Lear to question and inhabit his experience, and to live in and beyond the moment.' Lear was intimately aware of his awkward position as an outside observer, something that shaped his landscapes just as much as the weird imaginings of his nonsense poetry.

Lear painted trees with a careful eye, bringing out their individual characters and movement, while in his accompanying notes, he might describe a tree as 'semi genteel' or 'Vulgar', as if staking a claim for them in one of his fantastical botanies. Certainly he combined words and images in a manner that echoed his published limericks. While travelling, Lear kept detailed daily journals, several forming the basis for his illustrated travel books.

Lear periodically returned to the UK to sell work, though in 1846 he came at the request of Queen Victoria to provide 12 drawing lessons, the same year that saw the publication of both his first The Book of Nonsense and Illustrated Excursions in Italy. Between 1850 and 1851, he briefly studied at the Royal Academy Schools with the aim of becoming a painter of grand subjects in oils, but the need to earn a living caused him to cease attending classes. Bevis suggests Lear also had 'something in him which needed to stay unschooled.'

A year later, though, he was introduced to eminent Pre-Raphaelite artist William Holman Hunt, another figure with an interest in the eastern Mediterranean, in his case the Holy Land. Holman Hunt provided further lessons and his influence can be seen in the intense tones of works such as The Mountains of Thermopylae (1852), its translucent pigments layered on a white background.

A constant search for novel subject matter encouraged Lear to consider longer journeys, to Egypt and the Middle East. In 1858 he spent two months in Palestine, before heading north to Lebanon. With the author's evident wit on show, his journals became entertaining in their own right as well as setting in context many of his landscapes. Sketching in these environments was no easy task, with heat, dust and flies, alongside threats from locals – at the beautiful tourist site of Petra, Jordan, 100 tribesmen extorted payment from Lear for trespassing.

Even more of a disappointment was Jerusalem, still revered as a cradle of Christianity. Around the time of Tate's 'Orientalism' exhibition, the expert Briony Llewellyn noted how Lear was 'appalled not only by the decay into which the sacred city had been allowed to fall, but also by the internecine strife between the representatives of the various Christian sects supposed to be guardians of the Holy places.' Little surprise, then, that many of his depictions of the city are from outside its walls.

Ever the workaholic and consummate salesman, from 1862 Lear began to work up many of his sketches as watercolours for sale in their own right. By 1884 he had produced nearly 1,000 of them. A year after the 1870 publication of his final travel book, The Journal of a Landscape Painter in Corsica, heart disease began to take hold.

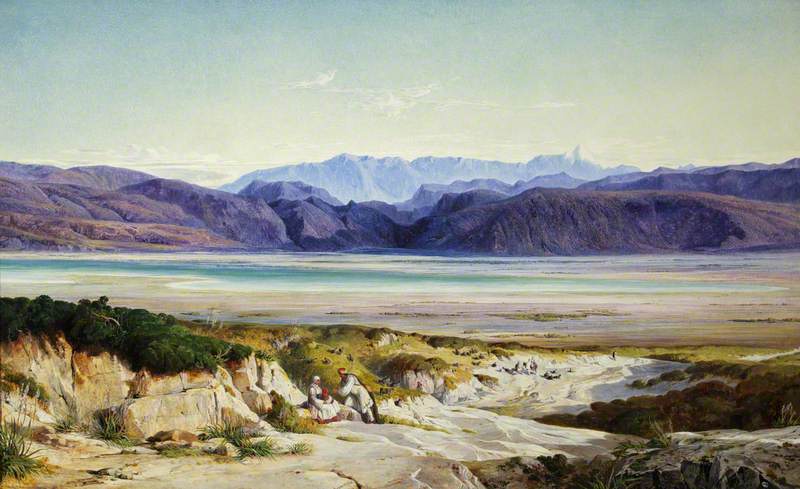

Lear settled at Villa Emily, Sanremo, Italy, with the express desire to halt his long journeys. However, two years later at the age of 60, he travelled to India, invited by Lord Northbrook, then Viceroy of the sub-continent. Although Lear returned, suffering from fatigue, after two months in Ceylon, this trip lead to the production of one of his most imposing works, Kinchinjunga from Darjeeling (1877), a representation of Kangchenjunga, one of the highest peaks in the Himalayas.

Following that trip, his health declined further and he became more sedentary, spending summers from 1878 to 1883 at Monte Generoso on the Italian Swiss border. From near his hotel, Lear was afforded breathtaking views across the region, as seen in The Plains of Lombardy from Monte Generoso (1880), the artist, as ever, looking hopefully towards the horizon. Eventually travel even within Italy became too difficult and he passed away in his villa, aged 75.

While Lear's nonsense poems have remained perennial favourites for old and young, his botanic illustrations and landscapes have continued to enjoy fresh appraisals. The Ikon show follows in the wake of, among other events, a display at The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, and a major exhibition at Yale Center for British Art.

The Pyramids Road, Gizeh

1873, oil on canvas by Edward Lear (1812–1888)

In 1988, the centenary of his death was marked with a set of Royal Mail stamps and, in 2021, his work The Pyramids Road, Gizeh sold for £801,500, 150 years after he painted it – an occasion that would have tickled a humourist, who was constantly hard up.

Chris Mugan, freelance writer

'Edward Lear: Moment to Moment' runs at Ikon, Birmingham, until 13th November 2022