For some artists, inspiration stems from the new and ever-changing. But for others, it's the figures and scenes most familiar to them which continually catch their attention.

British artist Celia Paul, born in 1959 in Trivandrum, India, falls squarely into the latter category. Throughout her long career, dating from the late 1970s onwards, Paul has repeatedly painted her own family members and slices of landscape with a personal significance, channelling her unique relationship with the people and places into reflective and acutely intimate images.

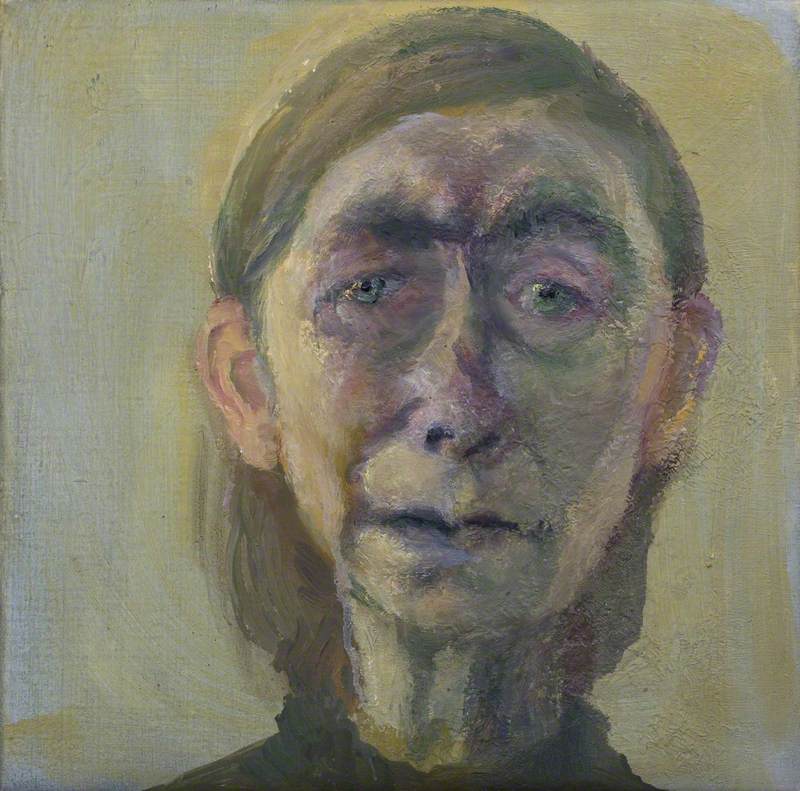

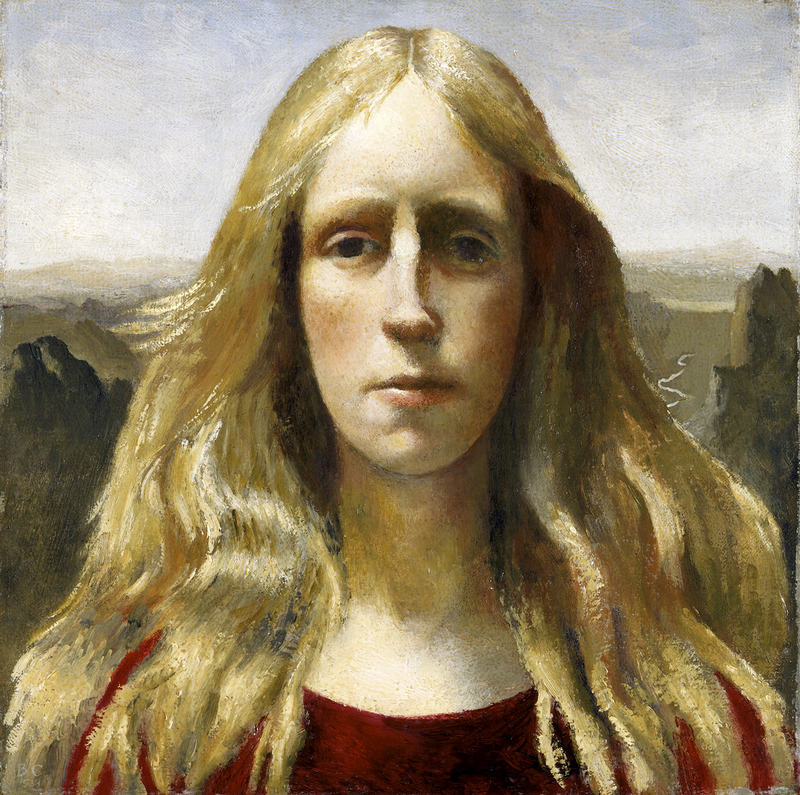

Portrait of Celia Paul

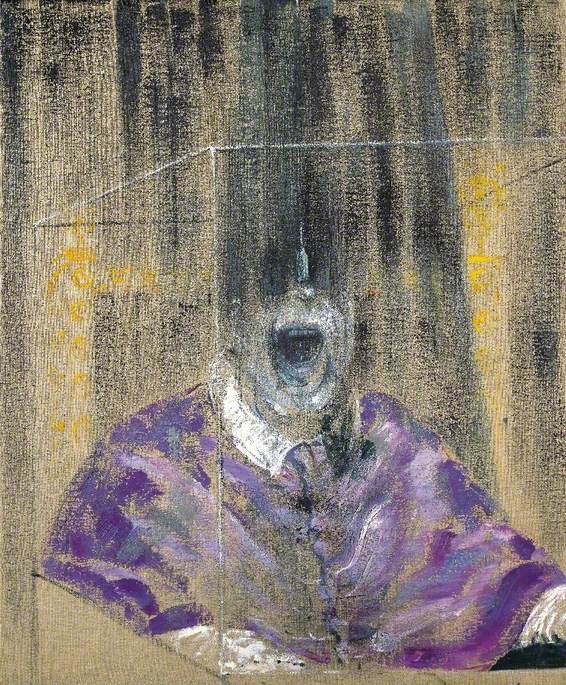

Paul is loosely categorised as part of the School of London group of painters, despite being considerably younger than the major figures associated with the movement: Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach and Lucian Freud.

The artist's commitment to figurative painting has seen her reputation in British art fluctuate over the years, including a decline of interest in the era dominated by the Young British Artists. Post-Millennium, there has been a resurgence of critical interest coinciding with the creation of some of Paul's most technically brilliant and emotionally adroit works.

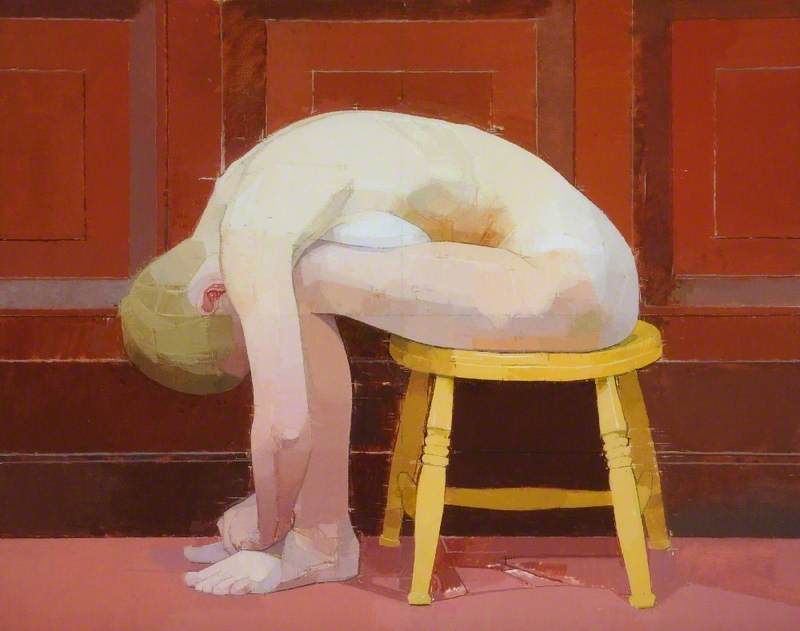

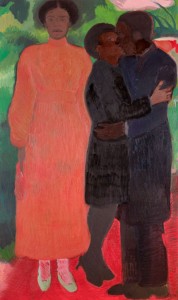

My Sisters in Mourning

2015–2016, oil on canvas by Celia Paul (b.1959)

An intensely private connection to the scene on the canvas and an ability to observe the subject unobtrusively, are both powerfully conveyed in Paul's My Sisters in Mourning (2015–2016). Showing four figures clothed in identical white smocks, the painting conveys a haunting sense of stillness.

The ethereal, smoky palette of chalky blues infused with sombre dove grey is shared with many of Paul's more recent paintings, while the accents of straw yellow centred on the sitters' faces echo traditional religious paintings. The title suggests the sisters are actively doing something – mourning – but the image itself demonstrates that to mourn is to be still, silent and reflective.

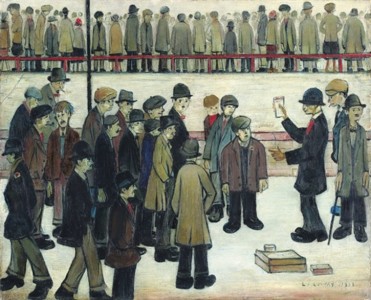

Family Group

1980, oil on canvas by Celia Paul (b.1959)

My Sisters in Mourning is significant because it marks the end of Paul's decades-long practice of painting her mother. Multiple studies of her family were already appearing frequently in her output while she studied at The Slade School of Fine Art from between 1976 and 1981. One of these, Family Group (1980), was declared by Lawrence Gowing, Principal of the Slade, to be the best painting ever completed by a student at the institution.

Another example from the same era is Mother (1976–1981). Despite the familiarity of the subject matter, this painting has a strikingly different tone and quality to Paul's later work. The brick reds, oak leaf green and ample use of black recall the impasto paintings of Frank Auerbach, while the despondent eyes and drawn-in cheeks bring to mind the portraits of German Expressionist painter Ernst Ludwig Kirchner.

Yet the devout attention to the features of a loved one, seen throughout Paul's career, is already present and stirring in its attention to detail.

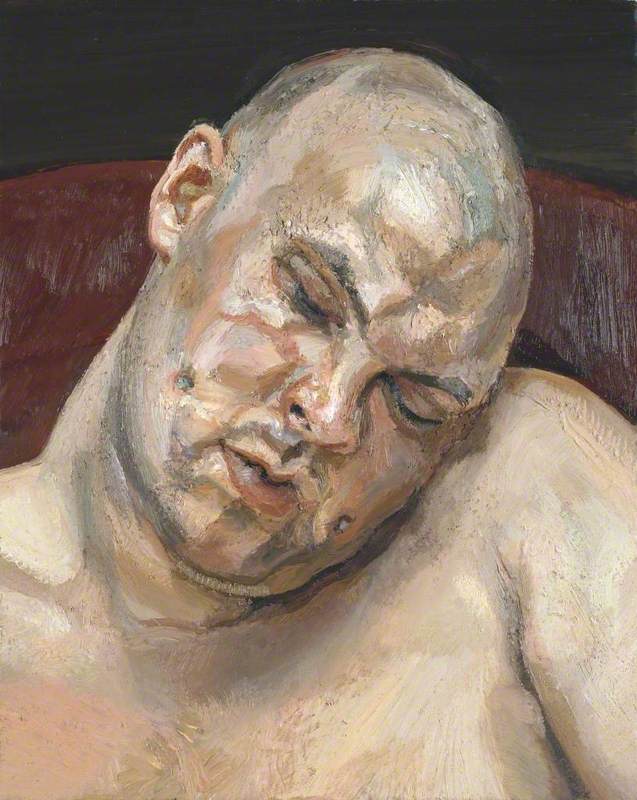

It is, however, another personal connection that has loomed largest in the responses to Paul's art. While at The Slade, Paul began a relationship with Lucian Freud, who at the time was teaching at the college. Their intense and messy relationship, including the birth of their son Frank in 1984, is documented by Paul in her memoir Self-Portrait, published in 2019, which asserts Paul's perspectives on Freud and her own, unique, artistic life.

Paul sat for Freud on numerous occasions, for example in Naked Girl with Egg (1980–1981), an experience Paul found deeply unpleasant. Doing so meant she became known as one of Freud's many female sitters and lovers, rather than as an artist in her own right.

As the author Zadie Smith has summarised, Paul's story is wrongly thought to be that of 'a muse who later became a painter', when in fact it is that of 'a painter who, for ten years of her early life, found herself mistaken for a muse.'

Paul's experience of sitting for Freud informs her own reflections on painting her friends and family. In Self-Portrait, Paul describes how her sitters' preferences for silence, small talk or – in the case of her son – listening to audiobooks infuses the finished artwork with different emotional tones and even changes how she paints. Her mother liked to use the time for silent prayer. For Paul, this meant: 'My painting was raised to a higher level, too, because of her elevated state. The air was charged with prayer.'

This aura of religious contemplation is apparent in the 2001 watercolour study, My Mother and the Cross, a work that can be read as a reference to her family's strong links to the Christian church – Paul's father was Bishop of Bradford and, once the family returned to England following missionary work in India, the children were first raised in a remote Christian community on Exmoor.

Similarities can be detected in Annela (2000–2001), an oil painting (the artist's preferred medium) of a friend. The figure appears as though walking through heavy mist or a wet gale. Accompanying the metallic greys and sparse shots of lightly golden sand are suggestions of bruised pinks that lend the picture an emotional warmth and humanity.

But it isn't just familiar faces that reappear in Paul's work. Landscapes by the artist also centre on scenes with a personal significance. One of these, In Front of the Museum (2008), captures a view of the British Museum, as seen from the artist's studio which is located directly across the street from the London landmark. Paul has worked at the same address since 1982, when Freud purchased the small flat for her.

In Front of the Museum

2008, oil on canvas by Celia Paul (b.1959)

In Front of the Museum has a similar mizzle-drenched feeling to the earlier painting of Annela. Unusually for Paul, an unnamed figure is pictured in the foreground of the scene. Just behind her looms the iconic façade of the building. Brighter yellow hues and sage greens emerge from the gloom the more it is studied, with a statue – a simplified version of the real-life frieze – illuminated in the centre.

The Brontë Parsonage (with Charlotte's Pine and Emily's Path to the Moors)

2017, oil on canvas by Celia Paul (b.1959)

Even Paul's landscapes which hold wider cultural significance have a close connection to the artist's biography. The Brontë Parsonage (with Charlotte's Pine and Emily's Path to the Moors), a 2017 oil painting, shows the home of the literary siblings framed by spindly trees and a shadowy graveyard.

When Paul's father was made Bishop of Bradford, her parents relocated to a house facing the direction of Haworth and the parsonage. Interestingly, some of the only portraits Paul has made of people unknown to her include two small portraits of Emily and Charlotte Brontë, suggesting the strength of affinity that Paul feels with the historic writers. Paul has also stated that a painting made by Branwell Brontë of his sisters informed My Sisters in Mourning.

Kate in White, Spring

2018, oil on canvas by Celia Paul (b.1959)

The prevailing sombreness of The Brontë Parsonage is in keeping with many of Paul's paintings, including those discussed above. Yet in recent years, a new and different emotion has begun to take precedence in her work.

Kate in White, Spring (2018) shows the artist's sister – her most regular sitter following their mother's death – seated by a window. The springtime sunlight streams through the panes, bathing Kate in an almost violent blast of illumination. The explosion of cream-coloured rays landing on the sitters' body and upturned face suggest the title 'Kate in White' could just as easily refer to the vast pale radiance as the dress worn by the artist's sister.

In a 2019 interview with the Guardian, Paul explains how 'It is quite telling of portraiture that love shines through. It is one of the reasons I know I can't paint people I don't love. If it works, it is only in a staged way.'

Self-Portrait, Standing

2019, oil on canvas by Celia Paul (b.1959)

Arguably, it is precisely this love that can be felt in Paul's paintings over the past few years. And, importantly, it is not just there in her depictions of other people. Alongside portraiture and landscapes, Paul has also produced numerous self-portraits. Many of these, for example, Self-Portrait, May 2010, clothe the artist in an aura of sorrow and anxiety.

But her 2019 work Self-Portrait, Standing bucks this trend. The artist stands with one arm softly resting across her waist, her expression focused but calm.

A vibrant gold light saturates the figure, turning her simple painter's dress into a glittering jewel-encrusted robe. The image radiates warmth and a healthy dose of love.

Rosemary Waugh, art critic and journalist