In Dombey and Son (1848) Charles Dickens introduces us to Miss Tox, an ageing spinster: 'when full-dressed, she wore round her neck the barrenest of lockets, representing a fishy old eye, with no approach to speculation in it.'

The locket Miss Tox wore was almost certainly a 'lover's eye'. These curious miniatures, usually of watercolour or gouache on ivory, depicted the eye of a loved one, sometimes with a brow sketched in, sometimes framed by a stray curl of hair.

In the context of her spinster status, and Dickens's use of the word 'barren' in relation to the eye locket (a fashion which in 1848 was perhaps already becoming a little passé), Miss Tox's unpleasing fishy adornment is calculated to intrigue the reader.

The craze for lover's eyes is usually attributed to a miniature of his own right eye that the Prince of Wales (later George IV) commissioned in 1785 from the painter Richard Cosway. George had it delivered to his mistress Mrs Maria Fitzherbert, whom he'd been wooing for some time, with a proposal of marriage: 'I send you at the same time an Eye, if you have not totally forgotten the whole countenance.'

Whether or not his eye clinched the deal, after their clandestine wedding the same year, Maria returned the compliment by giving him a miniature ocular portrait of her own.

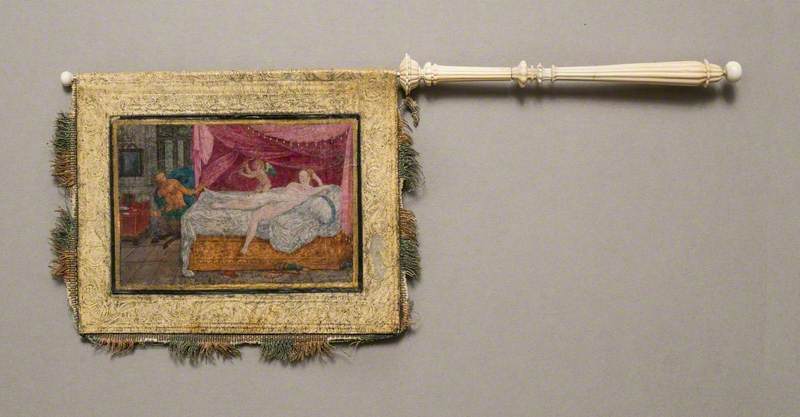

Typically, eye miniatures were created for smaller items of jewellery: brooches, lockets, watch-fobs, even rings – often with lavish surrounds – but they were also set into small personal items as well, such as toothpick or snuff boxes.

Eye of a Lady

c.1824, watercolor on ivory by unknown artist

An eye, being an anonymous detail and not the whole face, was a discreet way to send an erotic token to one's lover. But they also served as a straightforward memento of a partner or family member, like the keepsake lockets containing hair or portrait miniatures or, later, photographs.

Emotionally, the message of being watched over may also have played a part. They were popular among ever-superstitious sailors, away for long periods at sea and missing the comforts of a loved one. Richard Cosway, George Engleheart and William Wood, among others, painted many such eye miniatures, sometimes for whole families.

The poet William Cowper wrote to Dr John Newton in 1784 of an acquaintance: 'He has a pair of very good eyes in his head, which not being sufficient, as it should seem... he has a third also, which he wore suspended by a riband from his buttonhole.'

It was not only his eye that George IV gave Mrs Fitzherbert. In 1800 Richard Cosway painted his 'full countenance' for the Maria Fitzherbert jewel. This gold locket had two dozen rose-cut diamonds and one enormous central diamond that glazed and protected a miniature portrait on ivory of George when Prince of Wales. It remained in the Fitzherbert family collection until 2017, when it was sold at Christie's for a princely sum.

For a period Cosway became the king's Principal Painter, painting Mrs Fitzherbert many times. Another of his portraits of her was buried with the king, in fulfilment of his wishes.

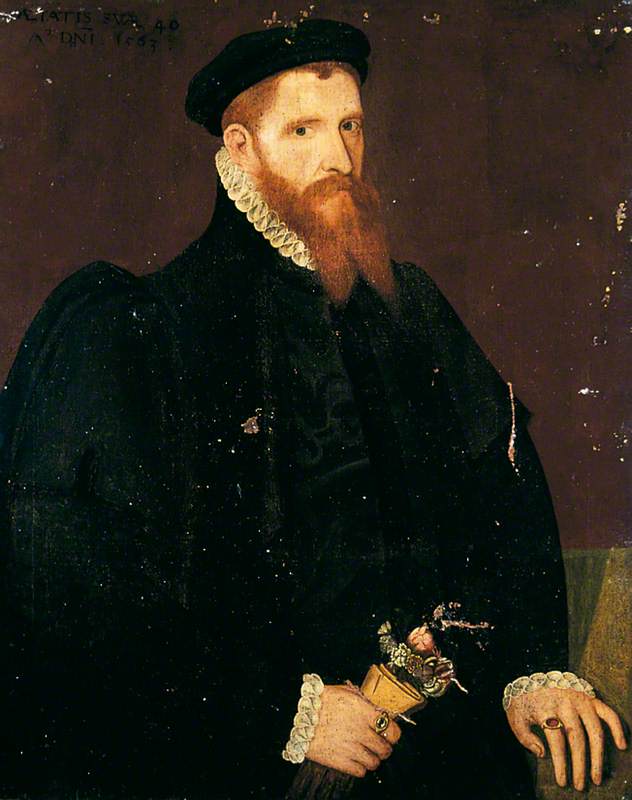

Such costly locket portraits were of course not new. The magnificent Lyte Jewel in the British Museum is a gold diamond-studded locket or tablet (as they are also known) containing a portrait of King James VI and I.

It was painted in 1610 by the miniaturist Nicholas Hilliard, and its elaborate setting thought to be by George Heriot, the king's jeweller, although Hilliard himself was a trained goldsmith.

The locket was presented to Thomas Lyte by James in reward for a 20-page genealogical table Brittaine's Monarchy drawn up for him by Lyte.

A portrait made the following year shows him wearing the jewel, one of the finest Jacobean lockets in existence.

The many portraits of James' forerunner, Elizabeth I, are known for the magnificence of her costume, with lavish jewels and gowns themselves encrusted with gems. Her lead-white skin and red hair contributed to her striking appearance.

Elizabeth I (1533–1603): The Pelican Portrait

c.1573–1575

Nicholas Hilliard (1547–1619) (attributed to)

The Swiss physician and traveller Thomas Platter described the queen in 1599 when she was in her mid-sixties:

'She was most lavishly attired in a gown of pure white satin, gold-embroidered, with a whole bird of Paradise for panache, set forward on her head studded with costly jewels; she wore a string of huge pearls about her neck and elegant gloves over which were drawn costly rings. In short, she was most gorgeously apparelled.'

Elizabeth I (The Armada Portrait)

16th C, oil on oak panel by unknown artist

Elizabeth was perhaps wearing something like the feathered headdress of her famous Armada portrait, commemorating the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588.

The queen's appearance was calculated to promote the material and imperial successes of her reign, aligning with her observation that 'We princes are set as it were upon stages in the sight and view of the world.'

The 'bird of paradise' mentioned by Platter was then another name for a parrot. But plumage in the hair, together with gemstones, became a popular adornment, as in Hayter's unflattering portrait of the mismatched wife of George IV, Caroline of Brunswick, wearing 'Prince of Wales' feathers, painted in 1820, the year her husband both took the throne and sought a divorce.

Caroline Amelia Elizabeth of Brunswick

c.1820

George Hayter (1792–1871)

Feathered headgear became increasingly splendid during the Regency period, tufts springing out of satin or gauze turbans, sometimes with aigrettes, either real, of egret feathers, or gem recreations, sometimes, as with Caroline, and as with Marie-Thérèse, the Queen Consort of France, tucked into their tiaras.

Marie-Thérèse-Charlotte of France (1778–1851), Duchesse d'Angoulême

1817

Antoine-Jean Gros (1771–1835)

Elizabeth I's favoured ropes of pearls were widely adopted as a fashionable means dressing hair or worn, as by Lady Mary Grey, in increasingly complex arrangements across the bodice.

As well as exhibiting wealth and status, gems were regarded as having a language of their own. In the Regency era, Thomas Miller's exceptionally popular Poetical Language of Flowers explained the supposed meanings of posies according to their different flower types, which prompted a similar fashion in gemstone symbolism.

Pearls, for example, denoted purity.

As such, they might be worn by the Virgin or Venus, or those in danger of conceding theirs.

But sometimes symbolism wasn't enough and you had to actually write the message explicitly.

Posy or poesie gold rings took their name not from flower bouquets but from the 'poetry' of their French, Latin or Old English inscriptions, forerunners of our modern wedding bands.

They were popular from the latter Middle Ages, and contained mottoes of love or faith such as 'Of earthli joyse thou art my choys', 'My longing keeps me awake' and 'Keepe faith till death'.

Later on, acrostic jewellery offered another form for declarations of sentiment. Popular from the early nineteenth century, rings, brooches and bracelets of this type spelled out certain sentiments or declarations encoded by the first letter of each gemstone (like acrostic verse).

Jean-Baptiste Mellerio, jeweller to Marie Antoinette and the Empress Joséphine, is credited with creating the fashion in France, where gem settings spelling out 'SOUVENIR' (remembrance) and 'AMITIÉ' (friendship) were popular. Napoleon Bonaparte was a fan of such ornament, spelling out 'J'adore' on jewellery for Joséphine. In Robert Lefèvre's portrait, Joséphine wears what appears to be an acrostic band of gems draped behind her diadem.

The Empress Josephine (1763–1814)

1806

Robert Lefèvre (1755–1830)

In England, Edward VII presented Alexandra of Denmark with an acrostic engagement ring, of beryl, emerald, ruby, topaz, iacinth (jacinth) and emerald, spelling out his nickname Bertie. (Her rings are just about visible in this much-reproduced portrait.)

Alexandra of Denmark (1844–1925), Queen Consort of King Edward VII

Luke Fildes (1843–1927) (after)

Jewellery has adorned us from the cradle – with christening necklaces of coral or blue beads, for their purported magical or mystical properties – to the grave – like George IV's locket, or indeed any number of burials found with jewellery from prehistory onwards.

In art, the concept of memento mori reminds us that this next life is coming and, for those of faith, to strive to prepare ourselves.

The portrait of the wealthy mercer Edward Goodman is emblazoned with texts entreating us to 'Be humble and meek, soberly, justly, piously', and that 'Each man's prayer is in his own heart' – a key tenet of his Protestant belief. His gold ring has a bezel, probably of enamelled gold, in the form of a skull.

The point is made more explicit in the portrait of his son Gawen.

Mourning jewellery worn by the relicts or family and friends of the deceased was widely prescribed.

Anne of Denmark's torchon-lace collar resembles the intricate steel-cut necklaces later fashionable in Prussia for mourning jewellery. Her simple black stone and pearl teardrop earring and black locket conform with the sober styles of deep mourning when convention permitted only black and white gems.

Two centuries later the widowed Mrs Payne likewise wears black.

Her necklace appears to be a large gold locket of a raised horseshoe ('lucky') design. Similar lockets contained one or two compartments, for portraits or a hair keepsake, as Mrs Payne's locket almost certainly did. It is strung on a necklace of probably Whitby or French jet beads. Just peeping out from her sleeve is a link-chain bracelet.

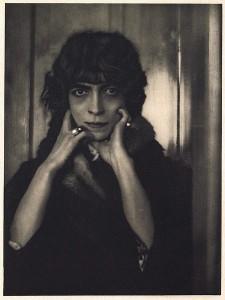

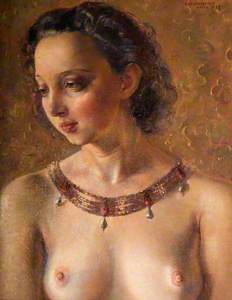

Painted in 1938 (the year the Nazis took over Austria), David Jagger's striking Jewish Refugee, Vienna is a sobering reminder of how significant jewellery can be to us.

This young woman, whose eyes suggest that she perhaps has lost pretty much all else, still wears five brightly coloured bangles. One wants to know their story. They are not of great intrinsic value in jewellery terms, perhaps. Nevertheless, to her, they are surely worth much, for reasons of sentiment and of self-identity.

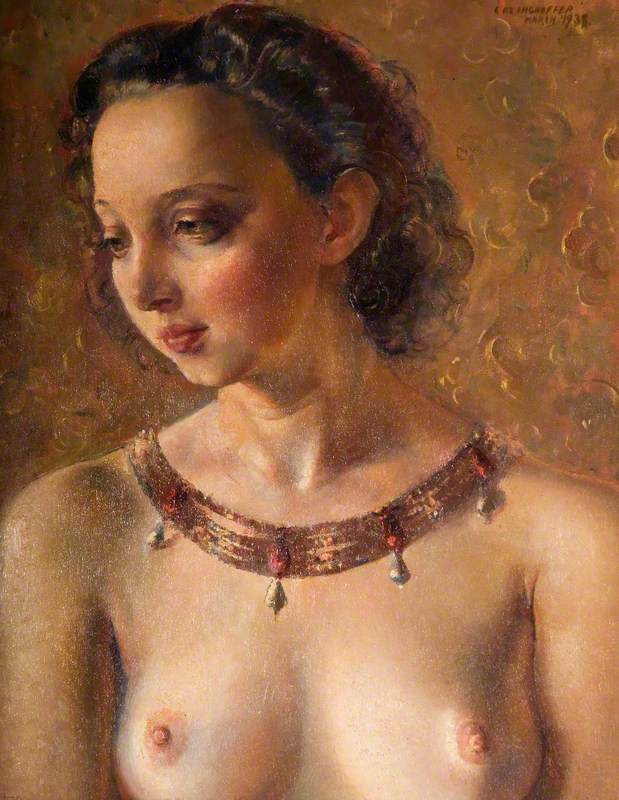

Equally intriguing is the jewellery in a painting made the same year by Clara Klinghoffer, an Austrian-born Jewish artist who also fled the Nazis.

In her sensitive study, The Oriental Necklace, she places the ornament at centre stage. Its wearer looks aside, appearing profoundly self-conscious in her display.

This necklace, showing off both its own beauty and that of its wearer, brings us back to the first function of jewellery as human ornament.

Sara Ayad, independent art researcher