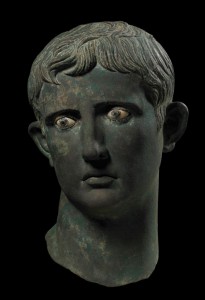

The Apollo space missions initiated a new age of wonder: the 1960s was a decade of hope and optimism based on science. This optimism infected artists, designers and architects ready to adopt new techniques and technologies. New buildings had their structures exposed, which produced highly expressive forms.

This bold architectural style swiftly conquered the world. It even found its way to the northeast of England to the small new town of Peterlee.

The Apollo Pavilion – the subject of a new film by HENI Talks – is considered the UK's first work of public art that merged the disciplines of art and architecture.

Peterlee was originally designed by Berthold Lubetkin in 1940, but after his ideas to develop high rises were considered too risky, due to the mining subsidence in the area, a different – altogether more artistic – vision was formed by British artist Victor Pasmore.

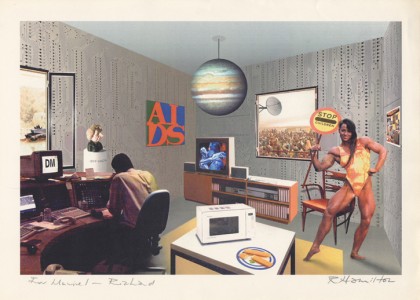

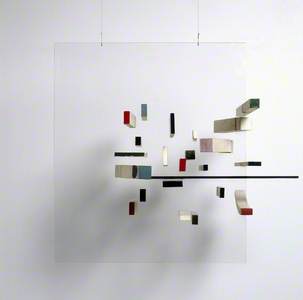

Considered one of the most promising artists of his era, Pasmore shocked his patrons and peers: from the late 1940s, he created striking compositions that considered space, colour and line. The art critic Herbert Read called this the most revolutionary event in post-war British art. Pasmore then began to expand his compositions into three-dimensional space and, with his assistant Richard Hamilton and critic Lawrence Alloway, he assembled an exhibition called simply 'an Exhibit' – an environment of suspended planes in wire, paper and Perspex.

His work played with movement, light, space and matter, the dualities of object and subject.

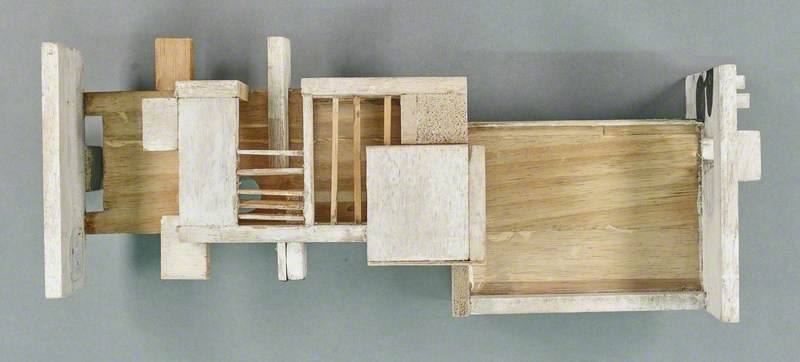

At Peterlee, Pasmore brought his compositions to life at a grand scale. What we see is an architecture of no utility and pure aesthetic. Similar in scale to the nearby houses on the Sunny Blunts estate, it's pure geometry cast in concrete.

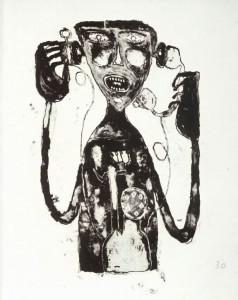

Abstract black compositions are integrated into the Pavilion, designed to be occupied and moved through. Pasmore conceived of art that was real, concrete and actual in its own right but without reference to anything external. It therefore generates tensions between the subject and object, and between the machine and the organic.

Pasmore created an artificial lake on which he determined that sculpture should be placed to act as a focal point and the gathering spot for the community. However, the relationship between the community and the pavilion was turbulent. Over time, the pavilion became neglected. Local youths began to populate the space, frequently tagging it with graffiti. As it fell into disrepair, the stair axis was blocked off, turning it from a habitable architectural space to an alienating lump of concrete.

Still from HENI Talk's film on Victor Pasmore's 'Apollo Pavilion'

Visiting it in 1982, Pasmore approved of the graffiti, saying that it humanised and improved it more than he ever could. He considered it a dialogue with that very community who had ironically rejected it and were calling for its demolition. But the 2000s saw a re-evaluation of Brutalist architecture and a campaign group of artists and cultural leaders was set up to save the Pavilion. It was eventually restored to its former glory and became listed in 2011.

Still from HENI Talk's film on Victor Pasmore's 'Apollo Pavilion'

A perspective that we rarely get a chance to see, that really shows the grand artistic vision of Pasmore, is from above. From that viewpoint, we can see how he arranged the low-rise houses around the estate, just like an abstract painting.

Still from HENI Talk's film on Victor Pasmore's 'Apollo Pavilion'

The Pavilion has taken on a new life: a grounded, terrestrial, abstract and concrete monument to the idea of progress. That same sense of inspiration can still be felt over half a century later.

Dr Stephen Parnell, architect, teacher and writer

Subscribe to the HENI Talks YouTube channel to be the first to know about new film releases