Sylvia Gosse (1881–1968) has been unfairly overlooked in favour of the male painters she knew, most famously Walter Richard Sickert (1860–1942). In fact, though she worked with Sickert, and her art shares some traits with his and that of the Camden Town Group – figurative, close-toned, interested in the ordinary and everyday – her fascination with working women as a subject, and the political nature of a painting she made from a photograph (pre-empting later developments in painting) make Gosse's art distinct.

Though her painting of Sickert may be her best known, there is far more interest in her life and work than her friendship with him.

The Gosses were a cultured and well-connected family. Sylvia's mother Ellen (née Epps) painted and trained in Ford Madox Brown's studio.

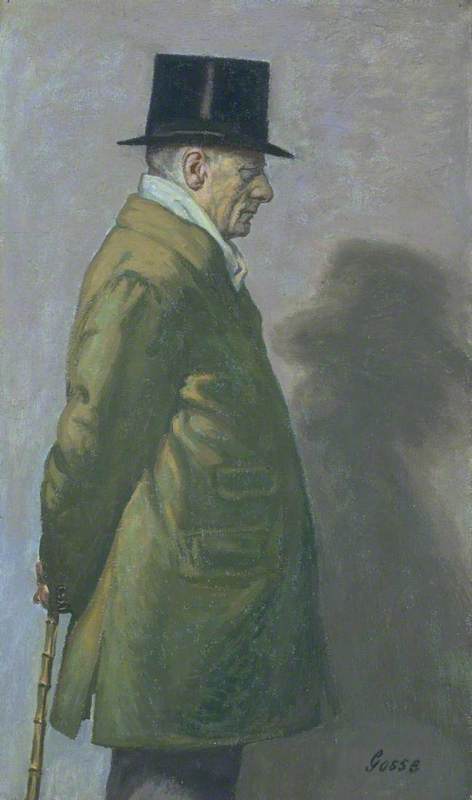

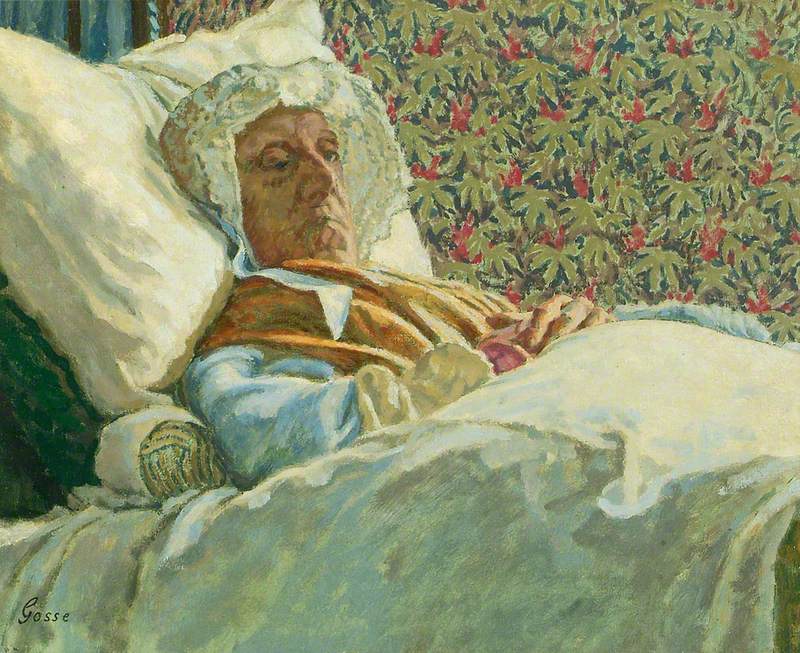

Sylvia Gosse's portrait of her mother in old age shows her in bed, a further image (now lost) portrayed her reading a letter from the poet Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967). Sylvia's aunt Laura married one of the most feted of Victorian artists, Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836–1912), and Sylvia's father was the critic and poet Sir Edmund Gosse (1849–1928).

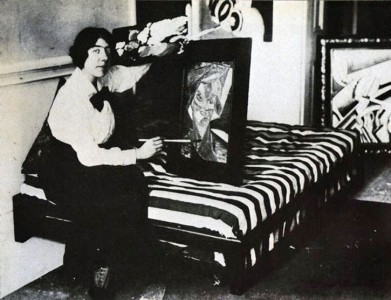

Sylvia Gosse trained at the Royal Academy and then met Sickert at her parents' house, where he was a frequent visitor. He taught her printmaking and then invited her to be co-principal of his art school at Rowlandson House, Hampstead. The name above the door there read 'Sickert and Gosse'.

Gosse's paradoxical position – as a woman in an artistic world which did not always value them – became clear during her time at Rowlandson House, and in her relationship with the modernist groups of which Sickert was a leader. According to Gosse's biographer and friend Kathleen Fisher, Gosse taught the less-able students at Rowlandson House, as Sickert would grow bored and impatient and dismiss them.

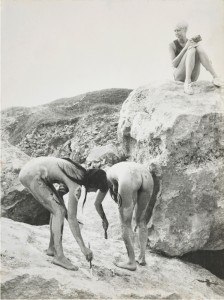

Her etching of a group of women students in smocks working in the garden there of 1912 is now in the British Museum, and a version of it was included in her first solo exhibition at the Carfax Gallery in 1913.

When the Camden Town Group was formed in 1911, for artists whose work was in tune with that of Sickert and Gosse, Sickert supported the painter Harold Gilman (1876–1919) in his decision that women should be excluded completely. It was only when Camden Town merged with the London Group in 1914 that Sylvia Gosse was allowed to join.

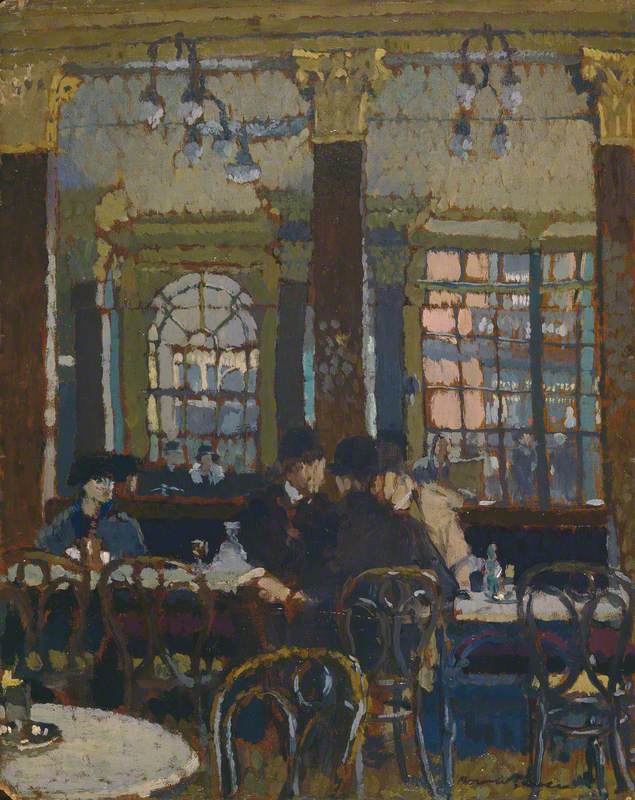

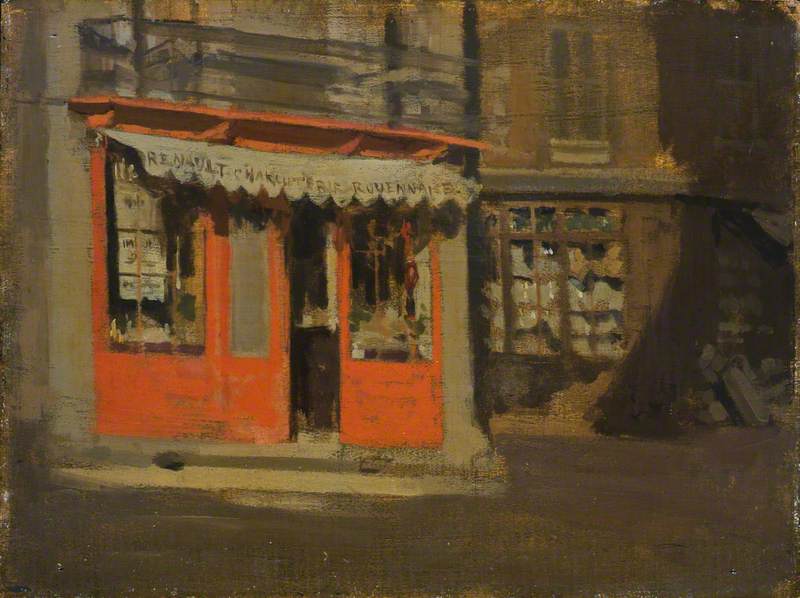

This complex relationship between women, art and modern life is encapsulated in Gosse's Les rentiers.

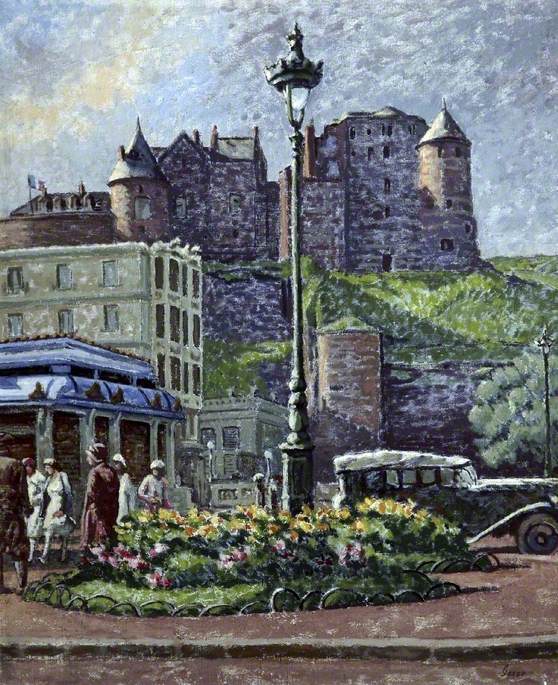

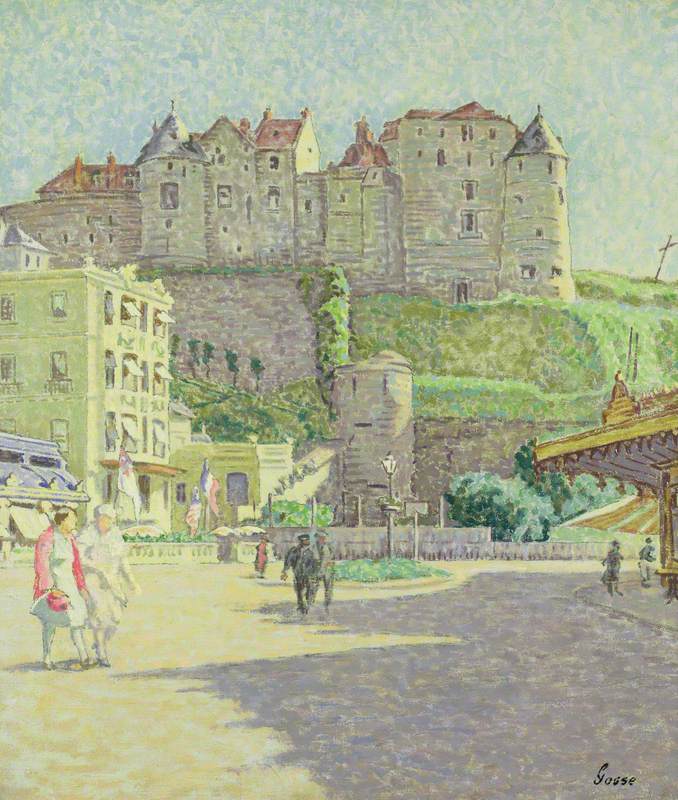

One of a series of paintings of French street scenes, in which she tended towards the prosaic rather than the picturesque, it has as its central motif a woman who fills the foreground. She is the dominant figure, but Gosse tells us little about her. She is caught in movement, we see a sliver of her face, and no distinguishing features. Her black hat and coat are not given in detail thought their shape suggest that the painting was made in the late 1910s or early 1920s. Instead, the focus is on the panorama unfolding behind her: the busy street, the group of men standing, talking.

It is as if Baudelaire's famous poem A Une Passante (1857), about a beautiful passer-by in a Parisian market who attracts the gaze and stimulates the pen of the male poet, has been turned on its head, and it is she who is now slipping through the city unseen herself but seeing everything: it is her eye that will come to rest on interesting subjects and capture them.

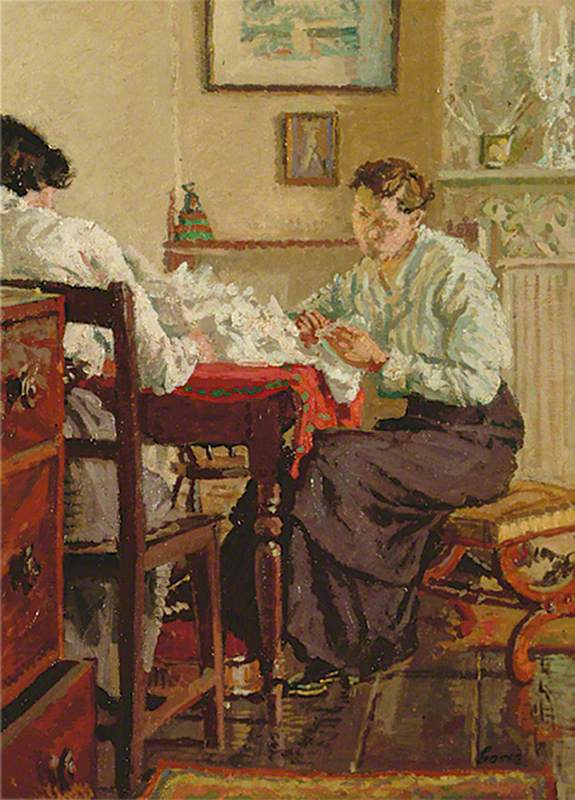

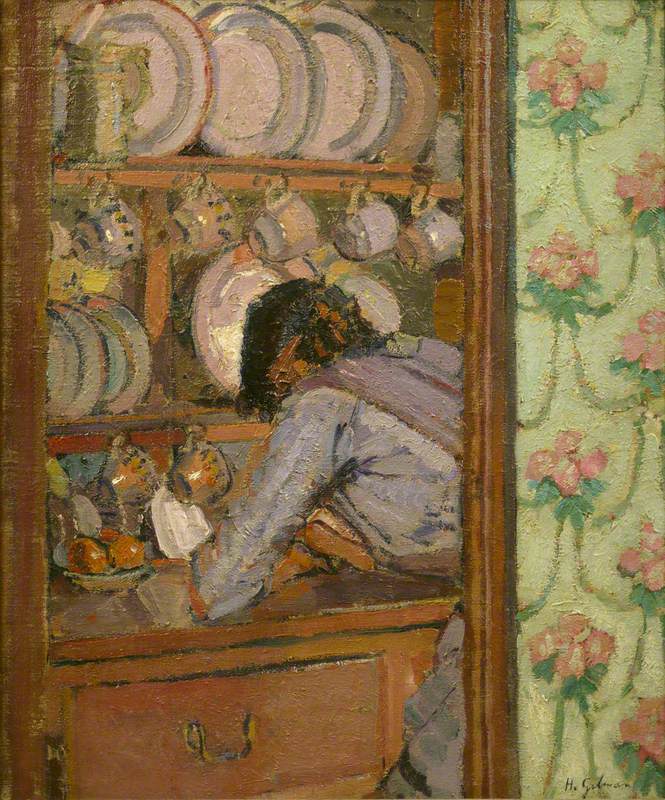

The subject of ordinary life, which took a particular form in the work of the Camden Town Group – the poor and dispossessed, boredom and squalor – took a different turn in Gosse's work, in her paintings and prints of women working.

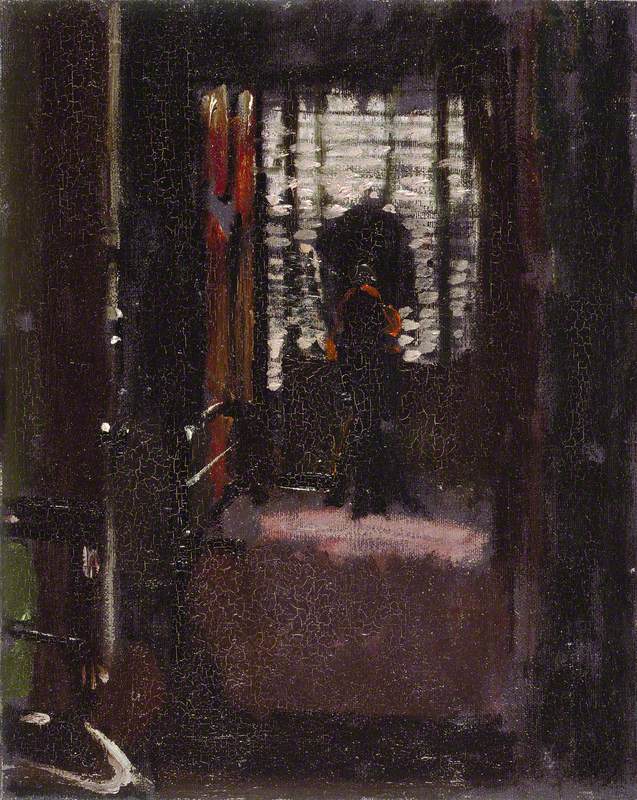

The Printer of c.1915 shows a woman labouring at a press, while The Nurse approaches her patient.

We see her as she is reflected in a mirror above the sickbed, but far from being a depiction of the supposedly feminine attributes of beauty or vanity, the device is used to show us an unglamorous workaday appearance.

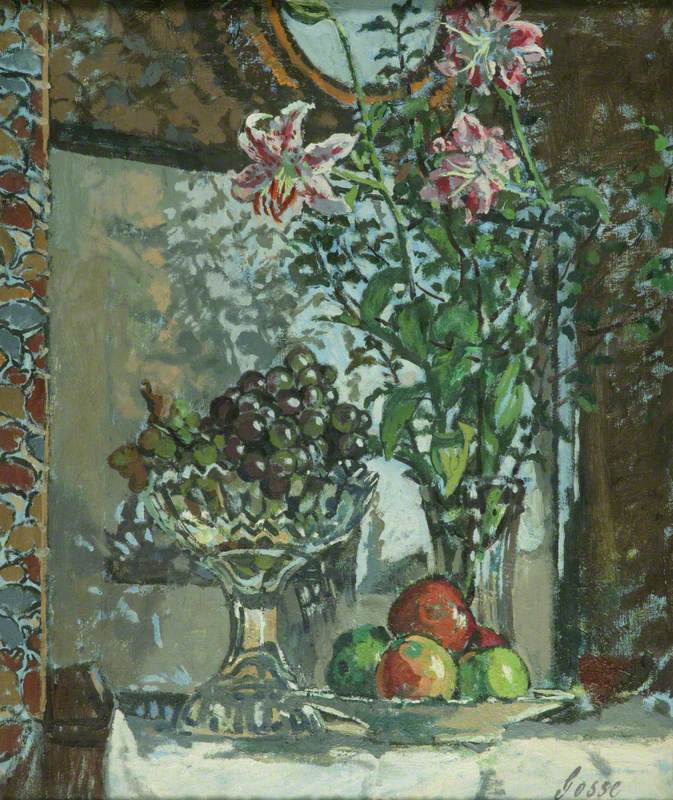

In her paintings of seamstresses, the intensity of the work in an ordinary interior is the subject.

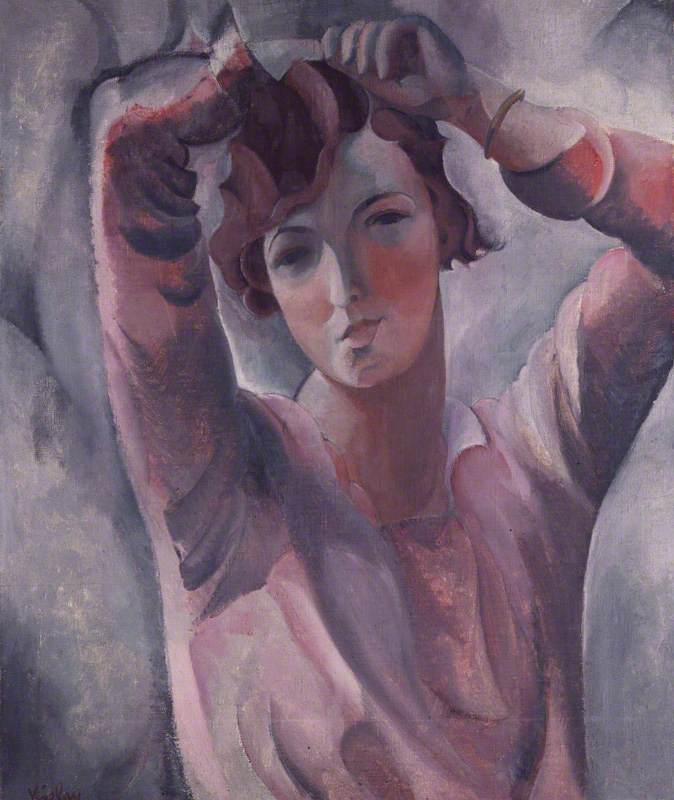

When Gosse approached the subject that Sickert had made famous in his series of paintings known as the Camden Town nudes – a naked female model on a bed with a clothed figure – she mimicked the subject (a watercolour interior in the British Museum shows a naked woman lying on a rumpled bed, a clothed and brooding man next to her on a chair), and then made it her own.

In her etching of two women (also in the British Museum), whose costumes suggest a date of mid-1910s, the younger figure on the bed wears stockings and a chemise, while leaning on the iron bed frame is another woman in outdoor dress, a hat, coat and boa. We are not certain whether the clothed female figure is a relation, mother or sister, employer, lover, or the artist herself.

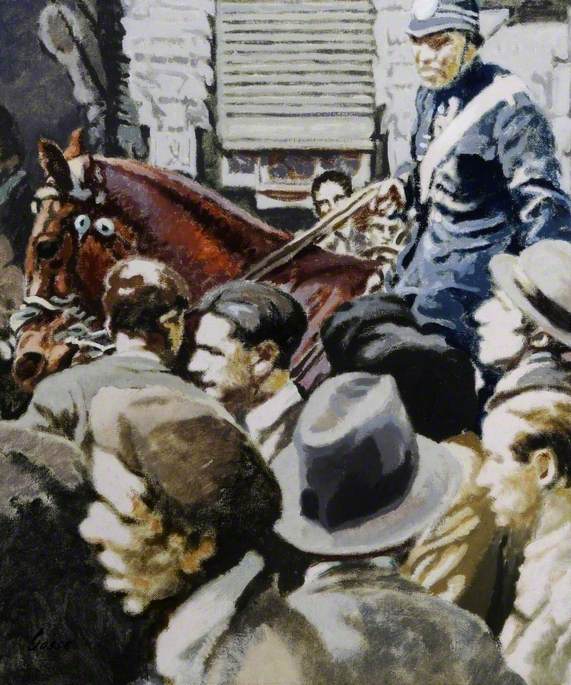

Like Sickert, Gosse was interested in the idea of working from what she called 'snapshot' sketches, made in front of the subject and then squared up to make oil compositions in the studio, and she also painted from photographs. Perhaps one of the most intriguing of her works in public collections is the painting Madrid Crowd of 1931.

She was known to be interested in Spain at this time, having made a portrait of the writer and philosopher Miguel de Unamuno (1864–1936) which is now lost. But in the painting of Madrid, Gosse depicted the riots in the Spanish capital during the fall of the monarchy and the formation of the Second Republic. A member of the Guardia Civil is shown grimacing and menacing on his horse, looming over the crowd of men.

A powerful – even ugly – image, concerned with political upheaval and impending violence, the flatness and blurring of the paint suggests chaos and that the source was a documentary photograph. It is completely, uncompromisingly, a painting of modern times.

Alicia Foster, curator