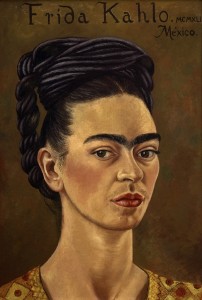

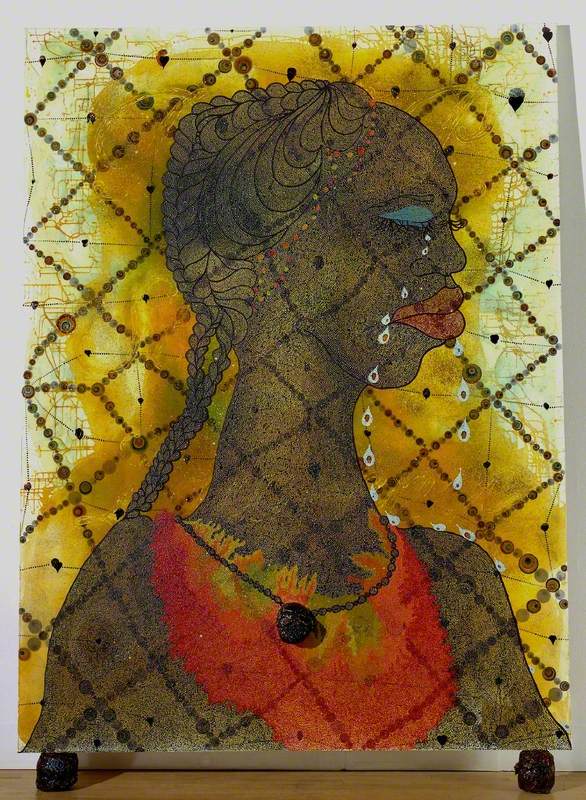

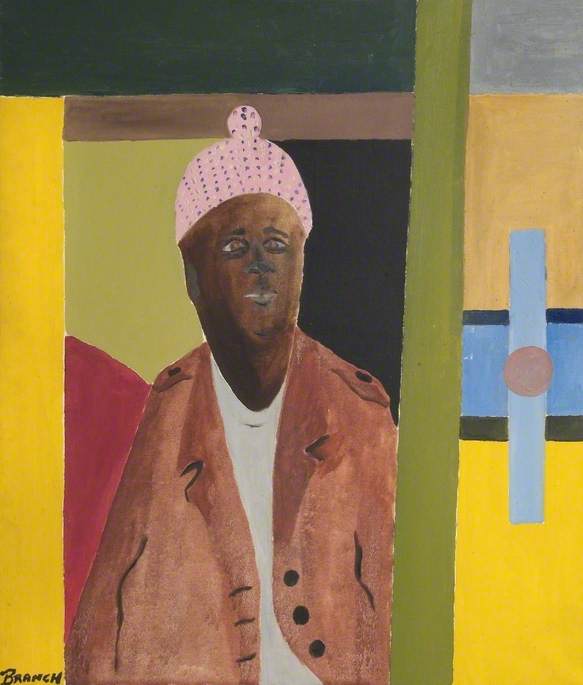

Colourful and feminine portraits, images representing internal emotions through patterns, paintings depicting historical events, animals and humans. When I read that Sonia Boyce (b.1962) had early on been influenced by Mexican artist Frida Kahlo (1907–1954) it made so much sense.

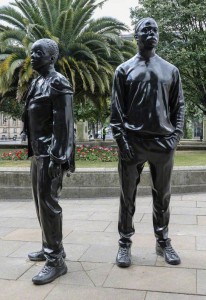

Image credit: Emile Holba

Sonia Boyce

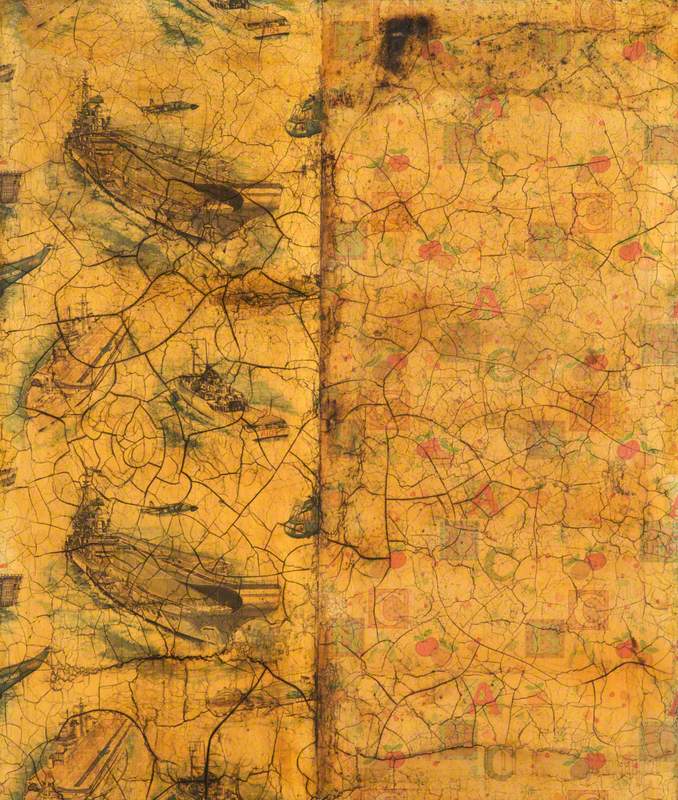

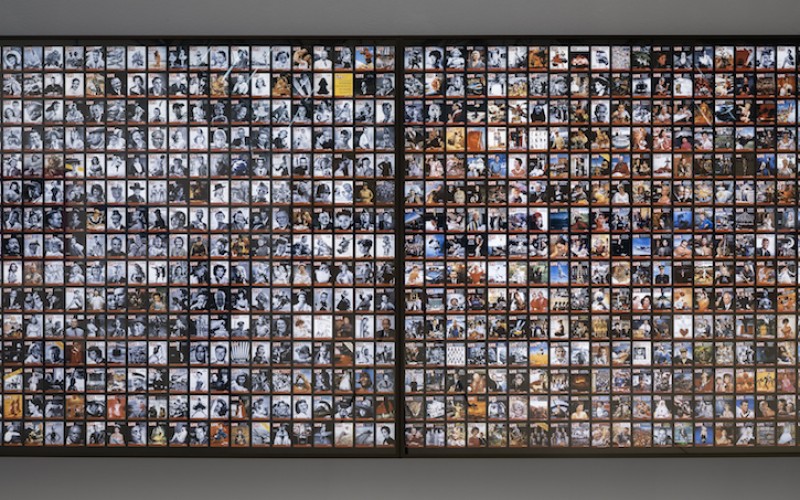

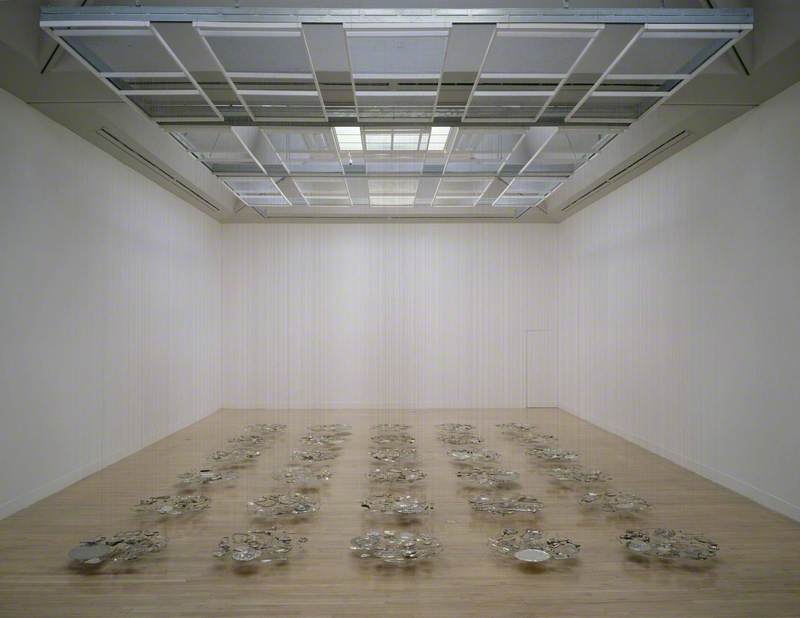

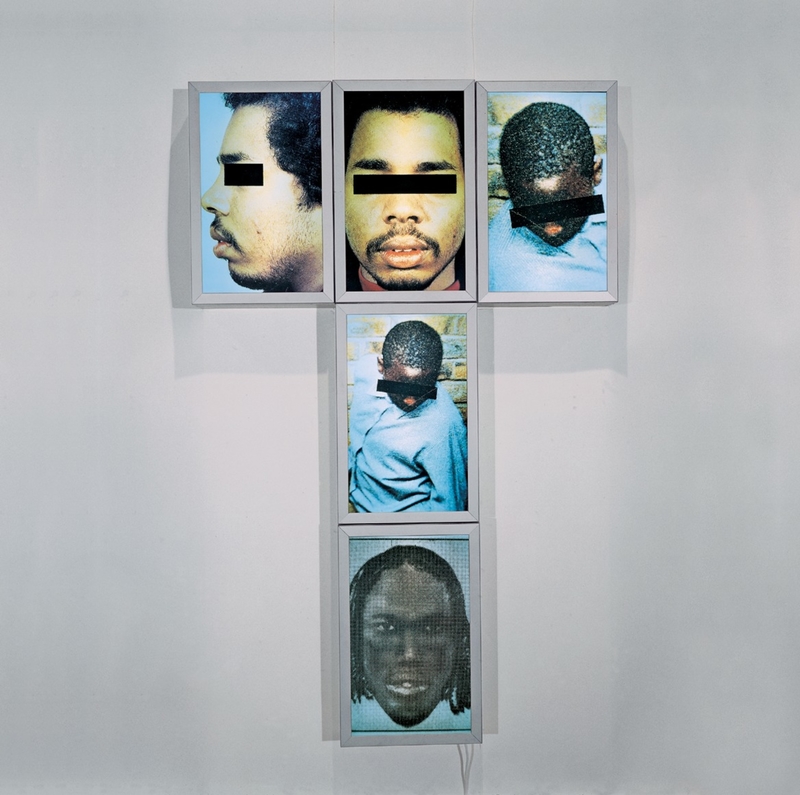

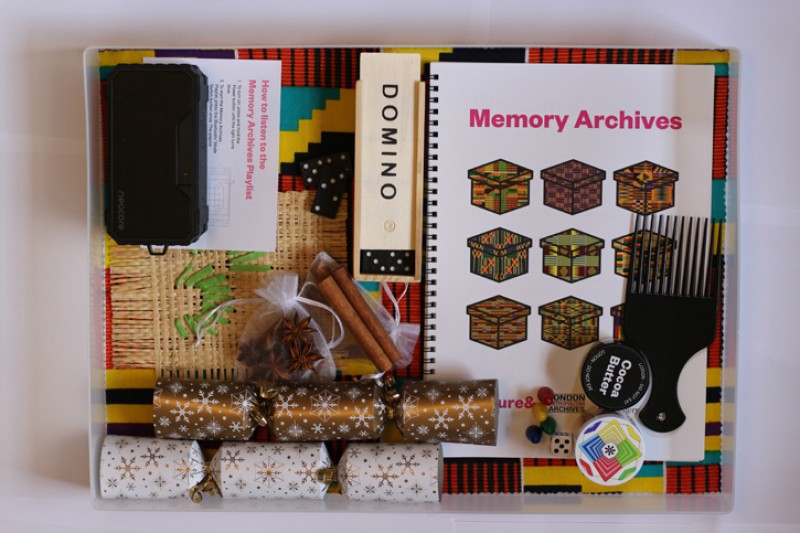

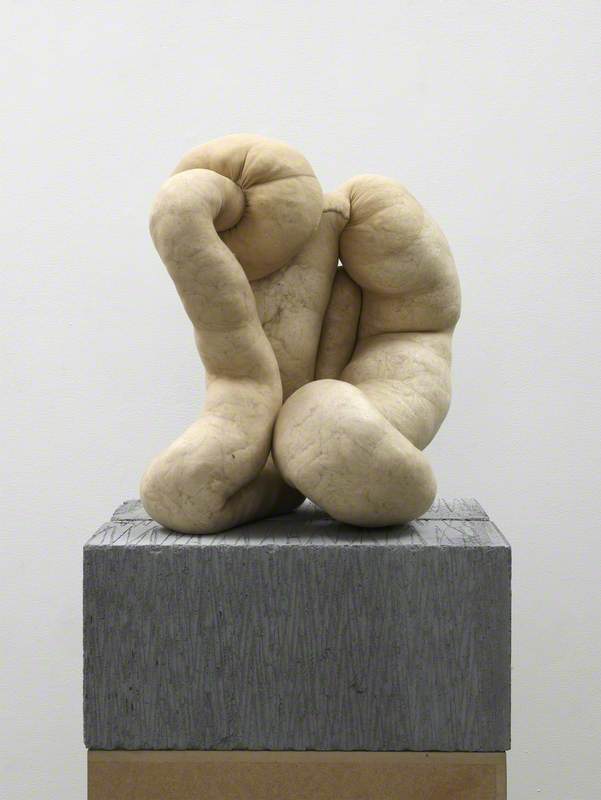

Boyce opened a new page in British art history, for women, Caribbean and also political artists, with aesthetically brilliant imagery and a strong personal narrative. She produces work involving a variety of media – drawing, print, photography, video and audio – exploring the interstices between sound and memory, time and space.

Born in 1962 in Islington, London, into a British Afro-Caribbean family, Boyce attended Eastlea Comprehensive School in Canning Town, East London. She was always drawing as a child, she said, so at 17 she decided to study art, and from 1979–1980 completed a Foundation Course in Art & Design at East Ham College of Art and Technology.

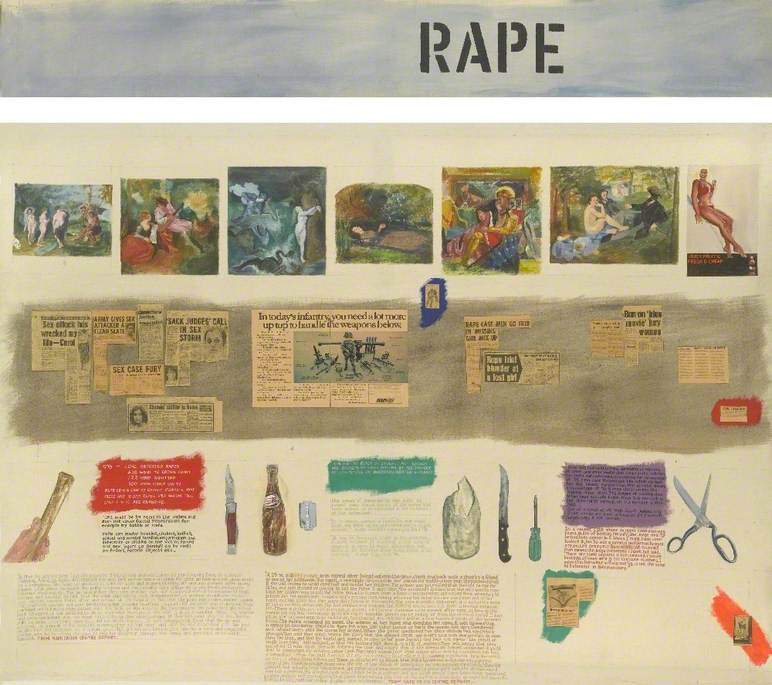

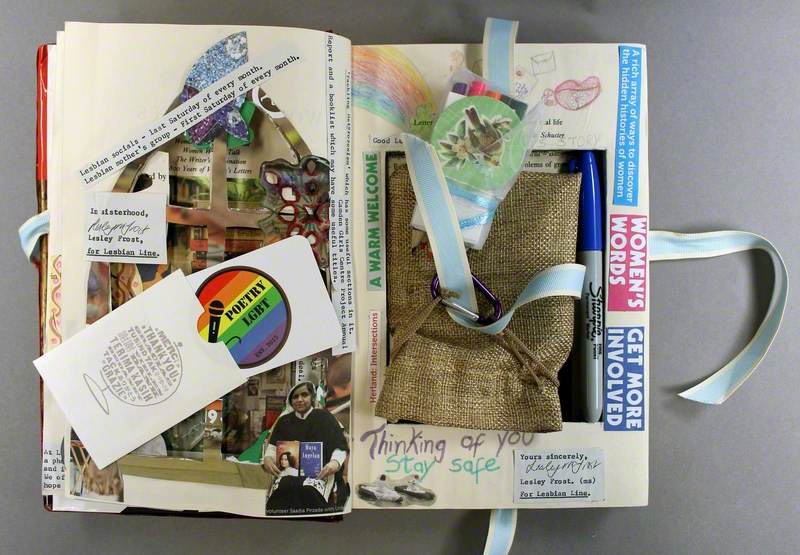

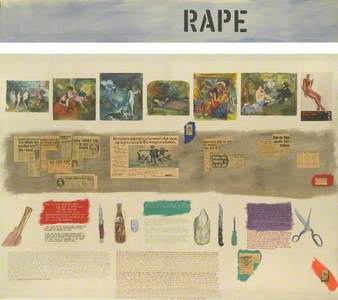

In Sonia Boyce: Beyond Blackness, art historian Anjalie Dalal-Clayton writes that the artist's early oeuvre was influenced by feminist artists Margaret Harrison (b.1940), Kate Walker and Monica Ross (1950–2013), and used an assemblage of texts, photography, drawings and magazine clippings. 'It was a revelation for Boyce,' Dalal-Clayton underlines, one which would come to define her practice.

In 1980 Boyce started a BA in Fine Art at the prestigious Stourbridge College in the West Midlands. But she soon felt unease. Her intuitions on postmodernism and mixed media were dismissed as delusional. 'It was very clear that I was somehow out of place,' she told The Guardian in 2018; 'the system hadn't anticipated me, or anyone like me. Even though there were a lot of female students, they were thought about as though they were being trained to become the wives of artists, not artists themselves. As a Black person, there wasn't a narrative at all.'

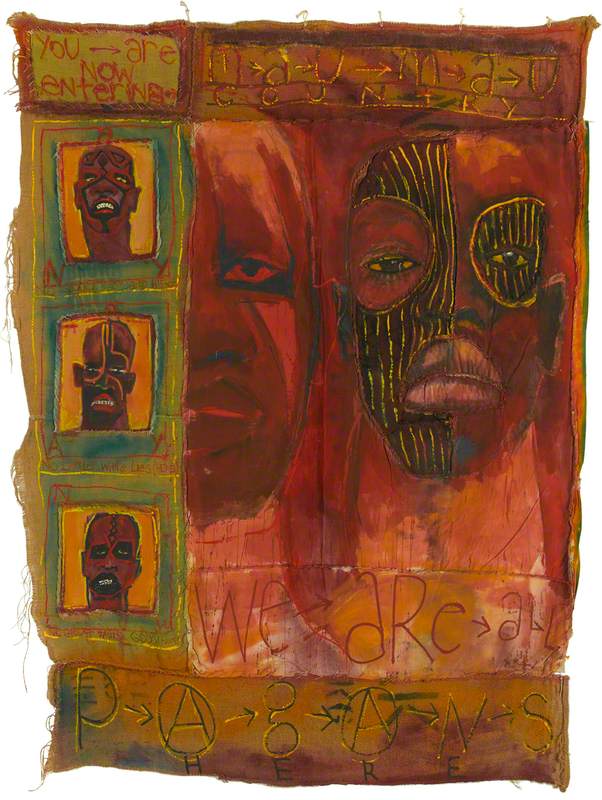

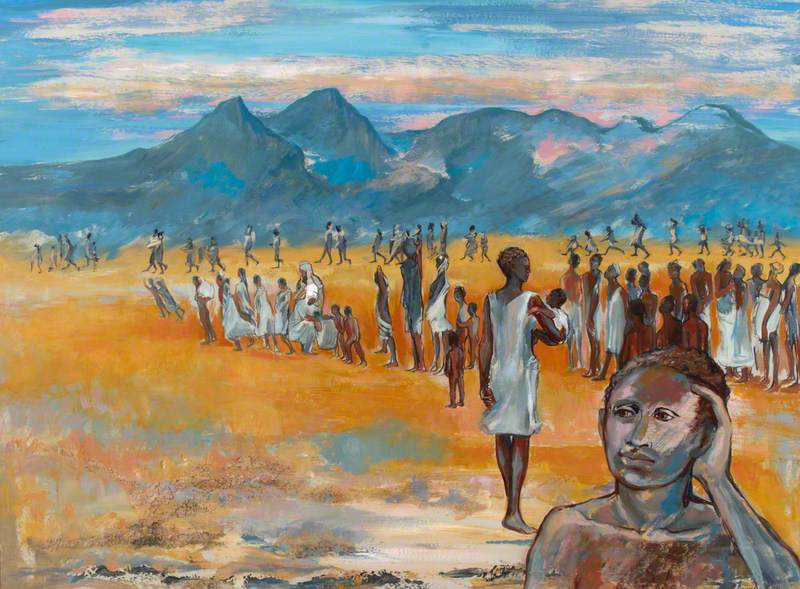

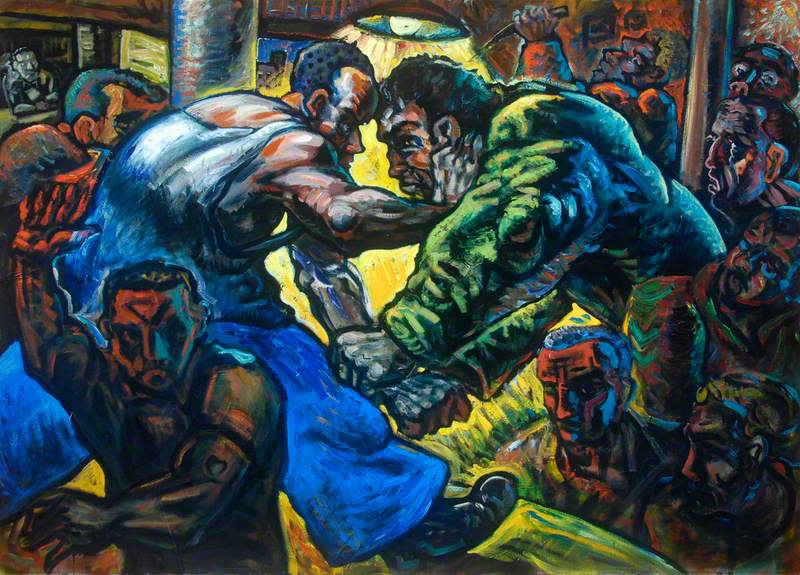

Luckily in 1982 she attended the first national conference of Black artists and met the Tanzanian-born painter Lubaina Himid (b.1954), a leading figure promoting the work of Black women artists and encouraging them in 'making positive images' of themselves. Sonia soon took part in this wider Black British cultural 'renaissance', a movement that arose in reaction to Margaret Thatcher's conservatism, and was embraced by artists such as Eddie Chambers (b.1960) and Horace Ové (b.1939).

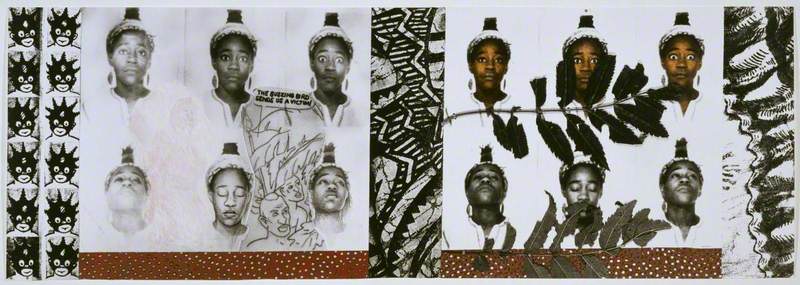

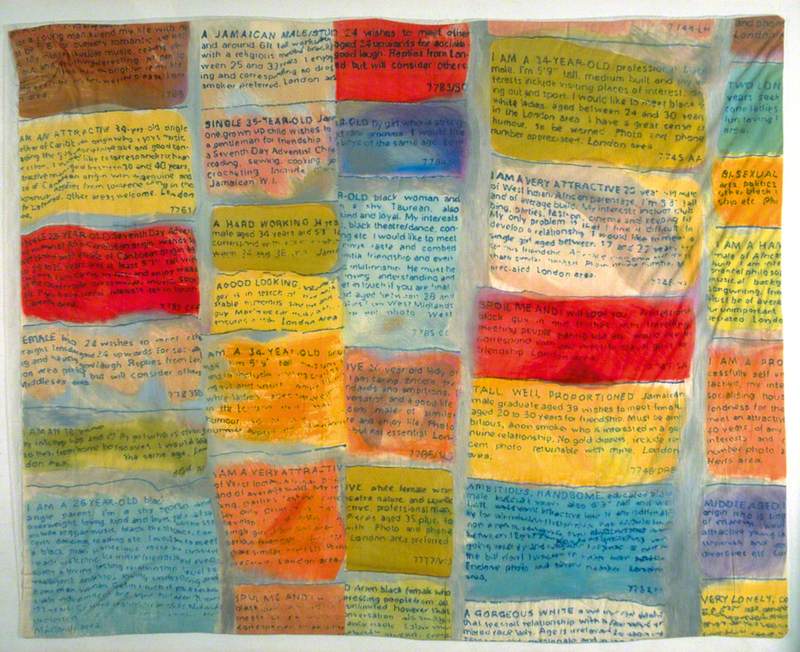

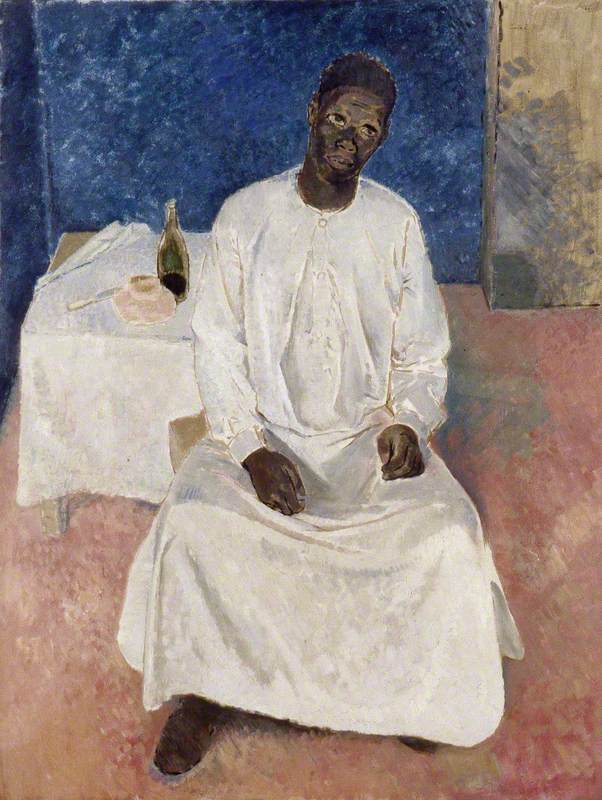

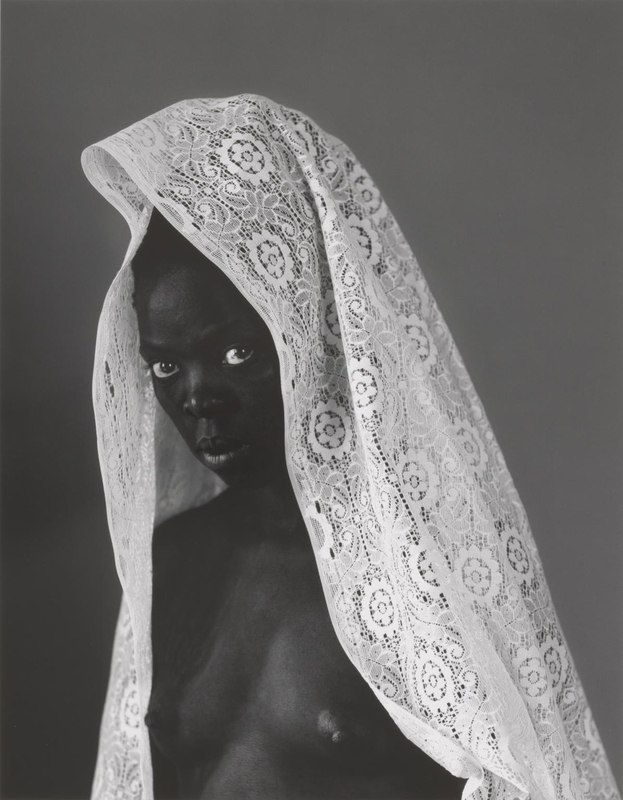

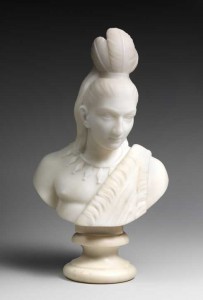

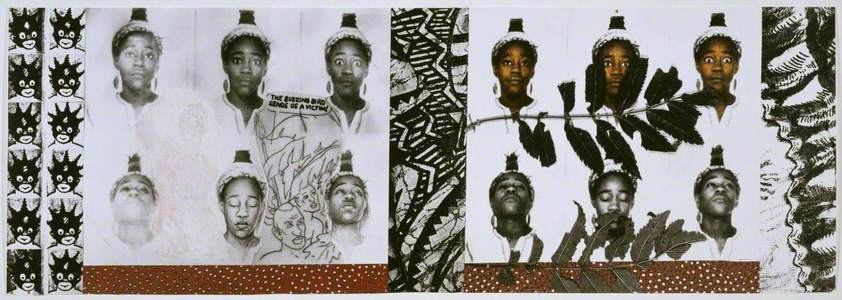

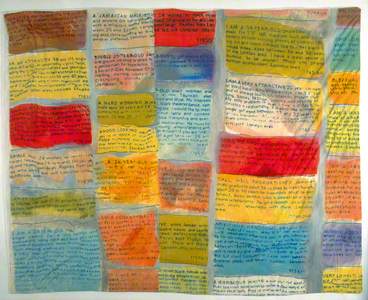

Boyce wanted to recapture the conventional English narrative surrounding the Black body, with the intention to challenge it. She started drawing herself into episodes of history from which people of colour had been excluded. She depicted friends, family and childhood experiences, including wallpaper patterns and bright colours associated with the Caribbean or the Windrush generation in England. In her pieces Boyce also included texts, using creolised language to enable 'vernacular culture to enter the space of art.'

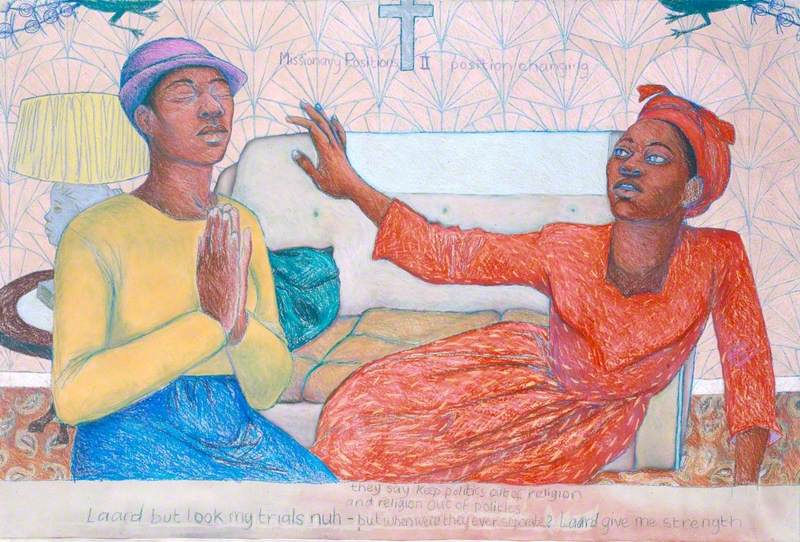

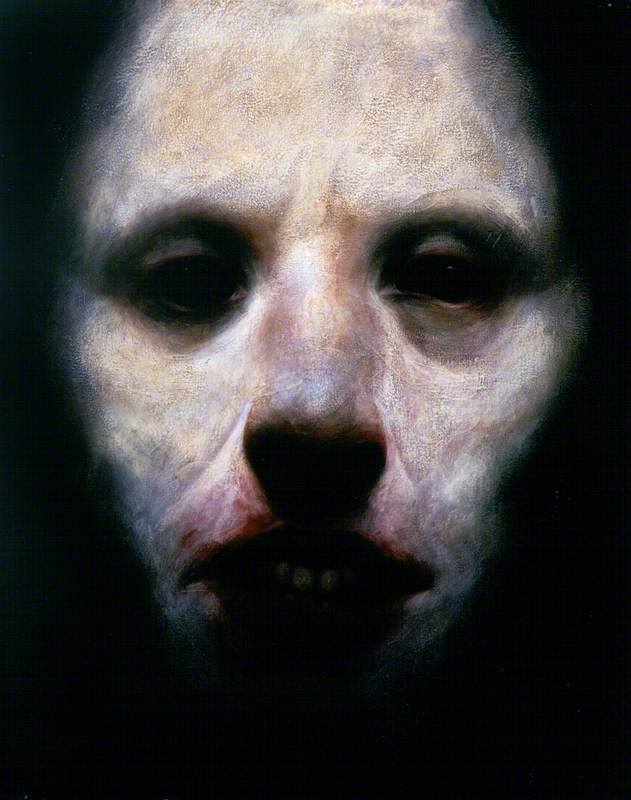

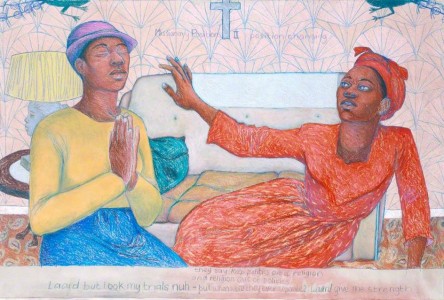

Curators began to notice how the artist examined her position as a Black woman in Britain and the historical events her experience was rooted in. As early as 1983, her piece Five Black Women was chosen to be exhibited at the Africa Centre, London. Sonia was only 21. Her works Big Women's Talk (1984), Auntie Enid – The Pose (1985) and Missionary Position II (1985) addressed issues of race and gender in day-to-day life, through large pastel drawings and photographic collages.

Made of watercolour, pastel and crayon on paper, Missionary Position II explores conflicting opinions on religious beliefs across different generations and cultures in Britain. The artist used herself as the model for the two figures, inspired (as mentioned earlier) by the work of the Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, then little known in the UK.

Boyce's practice was later influenced by the work of two other artists, according to Anjalie Dalal-Clayton: the feminist multimedia artist and performer Susan Hiller (1940–2019) and Donald G. Rodney (1961–1998), part of the BLK Art Group whose first exhibition 'Black Art An' Done' was shown at the Wolverhampton Art Gallery in 1984.

She became close to more Black British artists including John Akomfrah (b.1957) and his Black Audio Film Collective, as well as artist and curator Zak Ové (b.1966). Her work evolved toward collaborative art. Zak recalls: 'We all took part in the same group of artists coming out of early ventures into art together in and around Camden in London. We all felt like we were part of a family. Sonia exemplifies that sense of friendship in her work. She includes that closeness, offers positivity and radiance.'

In 1985, Himid selected some of Boyce's works for an exhibition she curated for the ICA titled 'The Thin Black Line'. And when Boyce was only 25, in 1987, Tate Modern bought her drawing Missionary Position II, making her the first British Black female artist to enter the collection.

During the 1990s, Boyce's work toured the UK and was widely exhibited abroad. Boyce began to question her freedom as an artist, expressing a growing desire to be understood beyond her iconic image of 'the first Black woman to…' In a 1992 interview with Manthia Diawara, Boyce commented: 'Whatever we Black people do, it's said to be about identity, first and foremost. It becomes a blanket term for everything we do, regardless of what we're doing.'

Boyce was soon invited to teach Fine Art studio practice in several art colleges across the UK. She is now a Professor of Black Art and Design at the University of the Arts London. Her practice keeps on evolving and in 2018 her first retrospective exhibition took place at the Manchester Art Gallery.

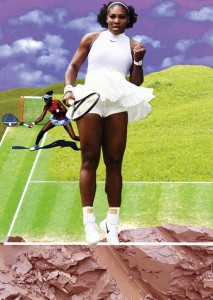

Now an OBE, Boyce will also be the 'first Black woman' to represent Great Britain at the prestigious Venice Biennale, in 2022. It is not her first appearance in Venice (she was included in the main exhibition in 2015 by late curator Okwui Enwezor), but this is still an unprecedented sign of recognition. On accepting the British Council commission, Boyce said: 'You could have knocked me down with a feather when I got the call to tell me I had been chosen to represent Britain at the Venice Biennale – it was like a bolt out of the blue.'

We are pleased to announce that Sonia Boyce OBE RA has been chosen to represent the UK at Biennale Arte 2021, presenting a solo exhibition of new work.

— British Council Visual Arts (@Brit_VisualArts) February 12, 2020

Find out more: https://t.co/EEwPqHIwRT

Photo Credit: Landscape of Sonia Boyce by Paul Cochrane, courtesy of UAL, 2013 pic.twitter.com/qinr0Q37yx

Boyce, as a Black artist, as a female artist, 'cannot help but be political in this world,' Hannah O'Leary, Head of Modern & Contemporary African Art at Sotheby's London, told me. 'I think often about the privilege and entitlement of white male artists that allows them the luxury of navel-gazing in their work. Much like Himid's Turner Prize win in 2017, the fact that Boyce became the first Black woman to achieve these milestones so late proves that we have only just begun to look at the representation of race and gender in this country, and that the true appreciation and celebration of this groundbreaking artist and her work, which resonates now more than ever, is clearly yet to come.'

Melissa Chemam, writer, cultural journalist, reporter