Doris Zinkeisen (1897–1991) and Anna Zinkeisen (1901–1976) are unusual in the history of art. The sisters both had careers as fine and decorative artists and worked together on the same commissions at times. Their work encompassed the extremes of twentieth-century experience: from the glamour and pleasure of high society and theatreland, to the horrors of the Second World War and the Holocaust.

Born four years apart in Scotland, they were united in their love of art from an early age. A family legend tells of them being reprimanded by their governess for sketching in their exercise books rather than studying. Both trained at the Royal Academy and, when they graduated, they launched their careers together, sharing a studio in London.

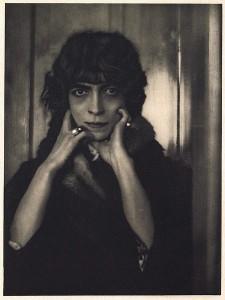

They made a name for themselves as portrait painters and commercial artists in the 1920s and 1930s. Doris became known for her work for the theatre. Her portrait of the actor Elsa Lanchester (later the wife of actor/director Charles Laughton) who was to become famous as the Bride of Frankenstein in the 1935 film of that name, is a study in the dramatic contrast between creamy skin and red hair, reminiscent of Augustus John's paintings of the Marchesa Casati.

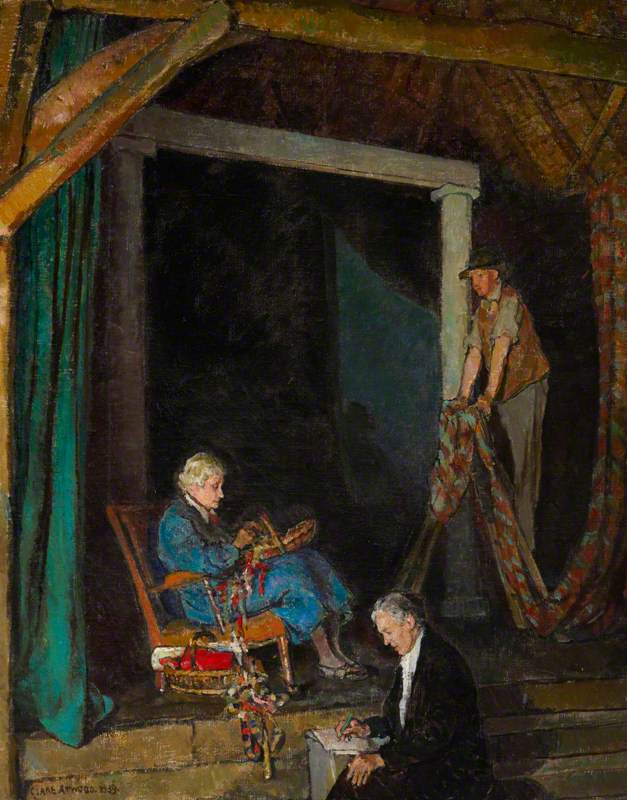

Doris also designed costumes and sets, notably for Noel Coward, and for Laurence Olivier's celebrated production of Richard III at the Old Vic, London, in 1944. She was invited, later, to design his unforgettably sinister makeup for the acclaimed film of the play.

© the artist's estate. Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

Doris Clare Zinkeisen exhibited 1929

Doris Clare Zinkeisen (1898–1991)

National Portrait Gallery, LondonIn a self-portrait, exhibited in 1929, Doris's flair for drama is given full expression in a stunning representation of the woman artist as a figure of beauty, but also talent. The embroidered shawl and fashionable hair and make-up are married to an unsmiling gaze and disappearing hand, a convention since the time of the old masters for indicating that the artist had captured themselves in the act of painting.

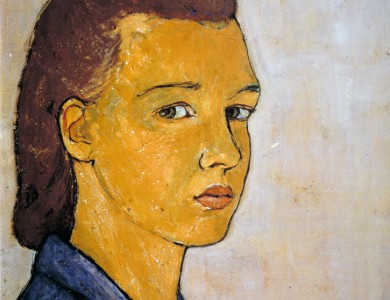

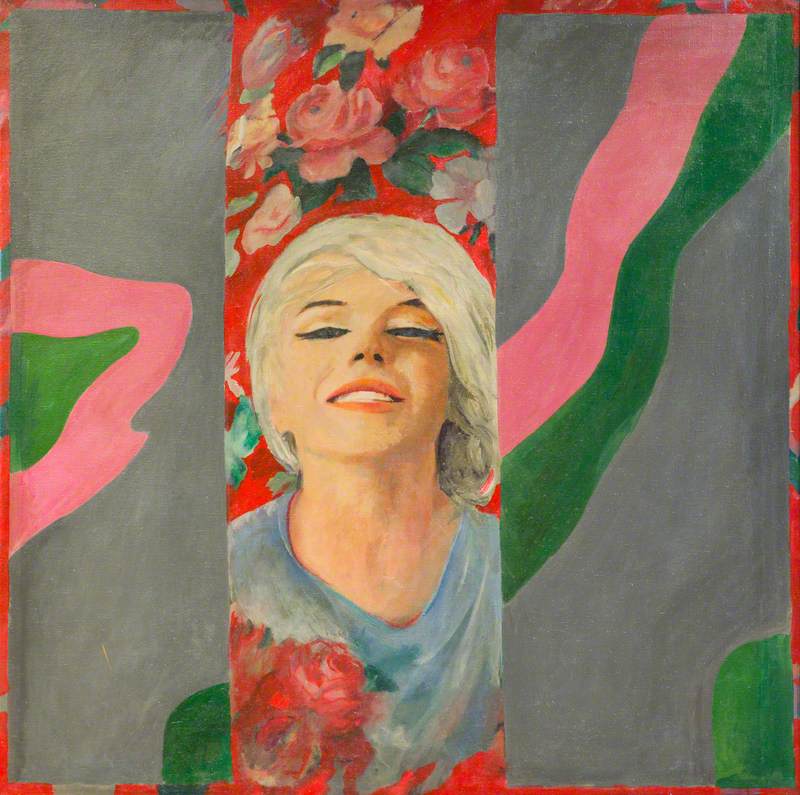

Her sister Anna's self-portrait, of 1944, is similar in its combination of style and seriousness. Anna shows herself with modish hair (this time the high-roll on the forehead of the war years) and red lipstick, but makes it explicit that this striking woman is also an artist to be reckoned with: the confident, combative gaze, the blue smock, the strong arm holding the palette and sheaf of brushes at her waist, all make a powerful statement of self as artist.

Like Doris, Anna had also established herself in commercial and decorative art, designing advertising posters, and painting flowers with a cool precision that seemed to unite the traditional Dutch masters with the contemporary classicism of Meredith Frampton.

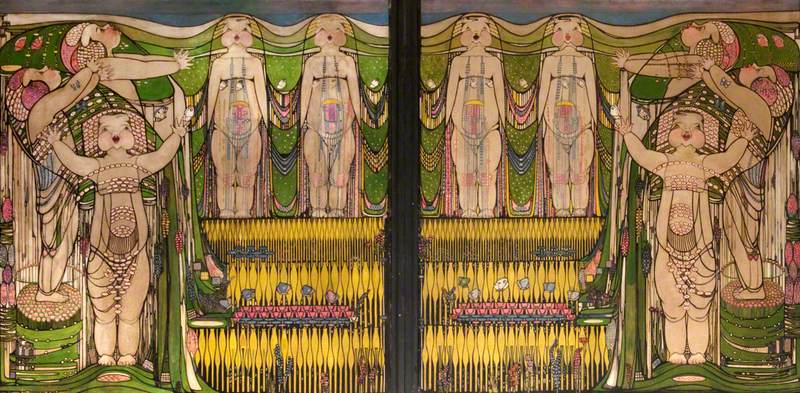

She also illustrated books and magazine covers, and the sisters accepted lucrative and prestigious joint commissions. In 1935 they worked together on murals for the ocean liner the Queen Mary, and the image by the famous photographer, Madame Yevonde, taken the following year, shows Anna in her blue smock painting on board with a crew of workmen in the foreground.

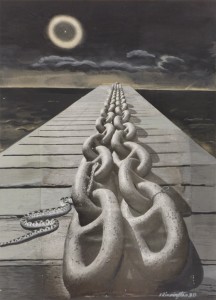

In 1944 they were asked by United Steel Companies to create twelve paintings of industrial subjects for the trade and technical press, which were collated into a book, This Present Age, in 1946. Three years later, they designed the ceiling decoration for the Morning Room at the Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum in Bournemouth, which can still be seen there: a trompe l'oeil painting in which figures from classical mythology such as Venus and Pegasus float and fly against a blue sky.

But the ground-breaking work for which the Zinkeisens should be best remembered came about due to a darker shared experience: that of being nurses and artists during the two great wars they lived through. Both women had served as VADs (Voluntary Aid Detachment workers) during the 1914–1918 conflict, however it was during 1939–1945 that they translated this first-hand experience of the effects of war into their best paintings.

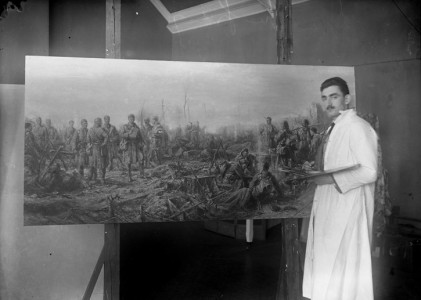

Commissioned by Kenneth Clark's War Artists Advisory Committee as the war ended in 1945, Doris – who had served as a volunteer nurse again over the previous few years – travelled through Europe to record the work of the British Red Cross Society and the Order of St John.

She entered the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp just after its liberation in April that year, among a small band of artists that included Mary Kessell and Mervyn Peake. The paintings she made there are remarkable.

© the artist's estate / Bridgeman Images. Image credit: IWM (Imperial War Museums)

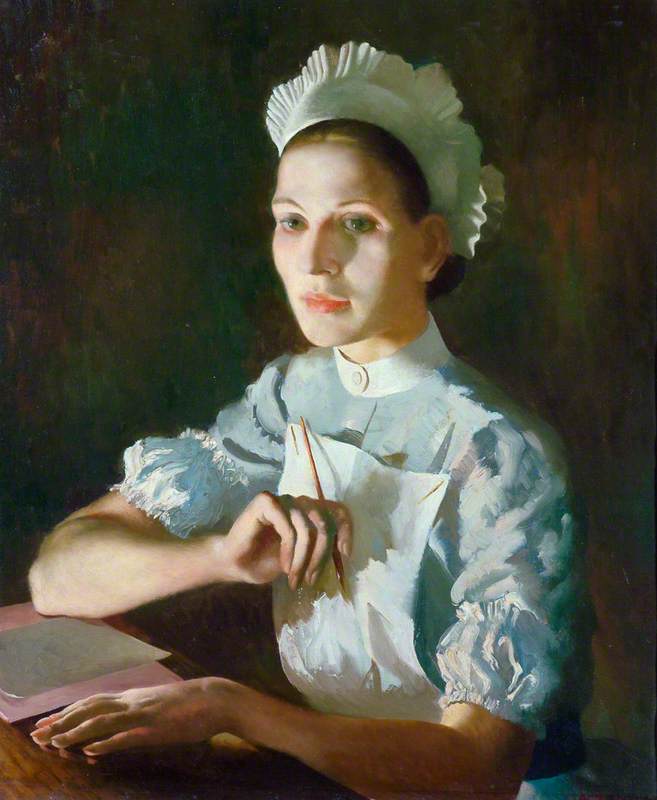

Anna Katrina Zinkeisen (1901–1976)

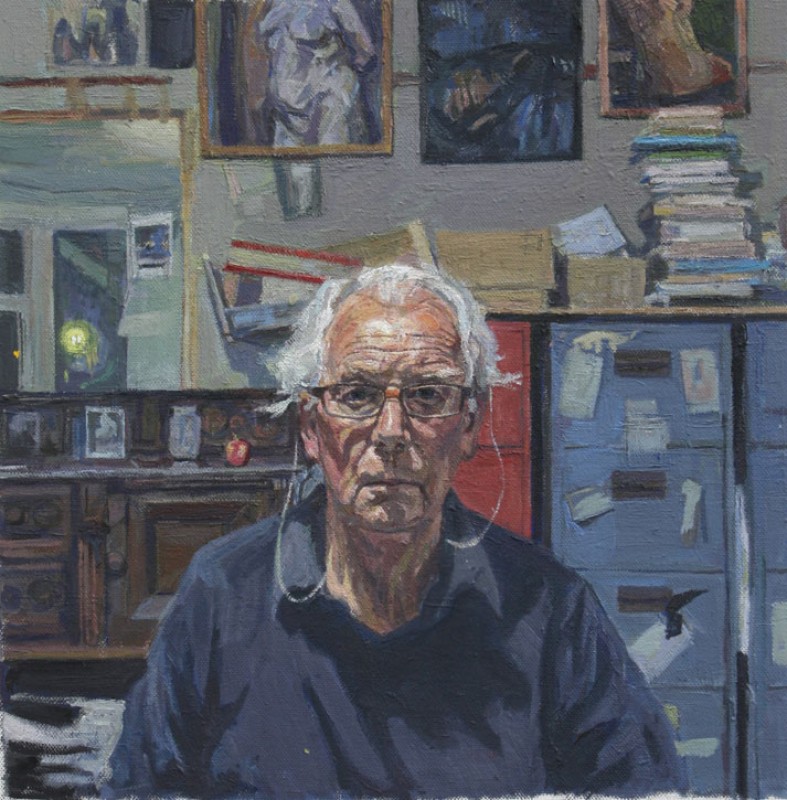

IWM (Imperial War Museums)The horror of what she witnessed – piles of corpses discarded like so much rubbish, grey-fleshed skeletal ex-prisoners being washed and de-loused by clean and corpulent Germans – is made all the more vivid by the lack of drama and the subtlety of the stripped-down palette. The experience never left her and she suffered from nightmares for the rest of her life. Anna, meanwhile, also volunteered as a casualty nurse at St Mary's Hospital, Paddington, and made medical illustrations of traumatised flesh to aid in the treatment of the wounded. She worked with Sir Archibald MacIndoe, the pioneer plastic surgeon, and painted him in action in the operating theatre.

In her self-portrait of 1944, Anna wears a bracelet with the insignia of the St John's Ambulance Brigade, and her painting, Night Duty, appears to be a portrait of her sister Doris in a nurse's uniform. Comparison of photographs of Doris with the sitter reveals the great similarity. As an image of an artist as nurse, by her artist sister, also a nurse, it is a moving homage to their shared and double calling, and an unprecedented moment in art history.

Alicia Foster, Curator