Artists share their visions, their emotions and their creativity with us. Artists can also share their lives and work as friends, as workmates and as collaborators with each other.

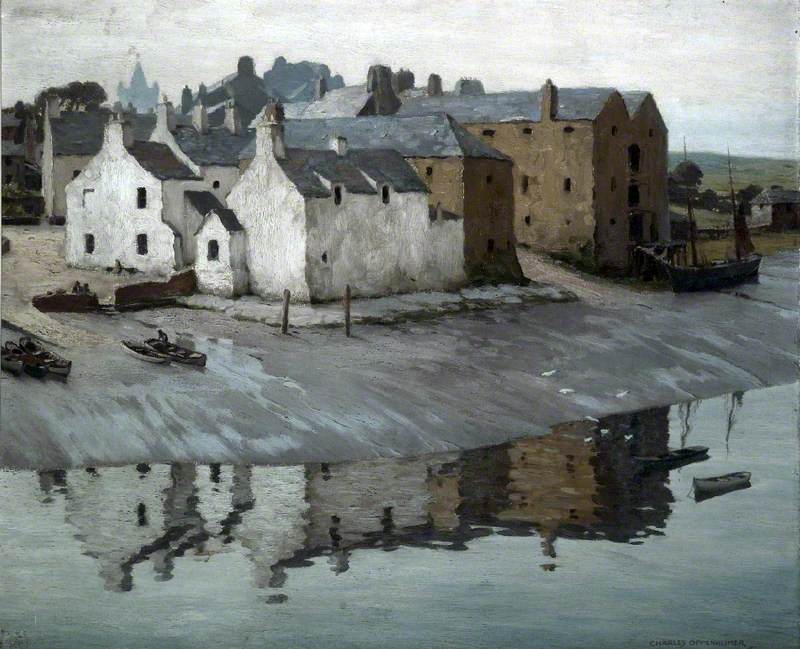

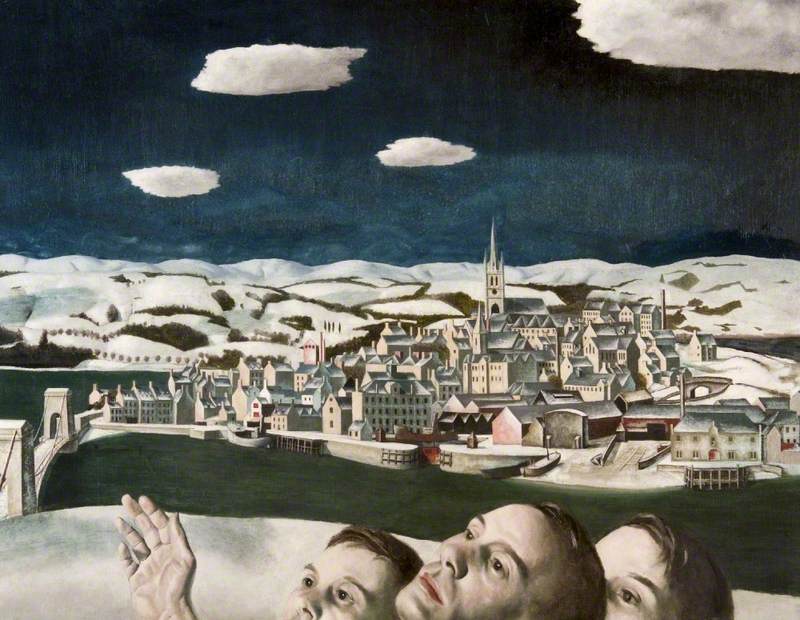

An artistic community can have a significant influence on a place and its people, and, during the 1920s, the coastal town of Montrose became the location for a Scottish arts renaissance by a dynamic group of writers, artists and poets. Also living and working in Montrose at this time were William Lamb and Adam Christie.

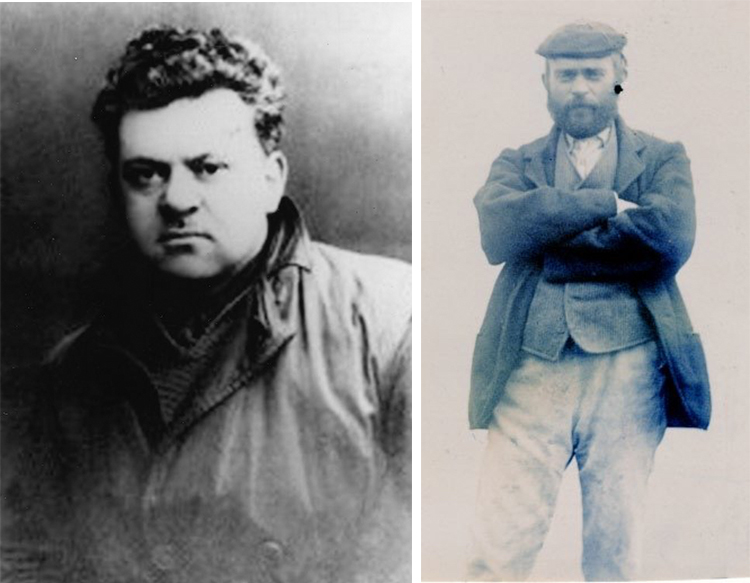

William Lamb, left, and Adam Christie, right

Lamb and Christie were artists who happened to already be there. They blended in with what was going on in their own way, but they were always artists on the edge of the scene.

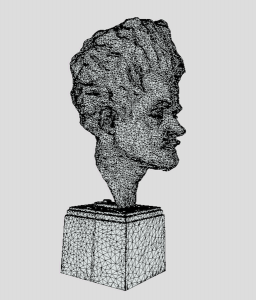

William Lamb (1893–1951) was born in Montrose and studied art in Aberdeen and Edinburgh. After the First World War, he returned to Montrose and worked on sculptures of people he saw around the town.

From the 1920s until his death in 1951, Lamb produced many sculptures featuring local people. He was also commissioned to sculpt royal figures and many of the creative people who were living in Montrose at this time.

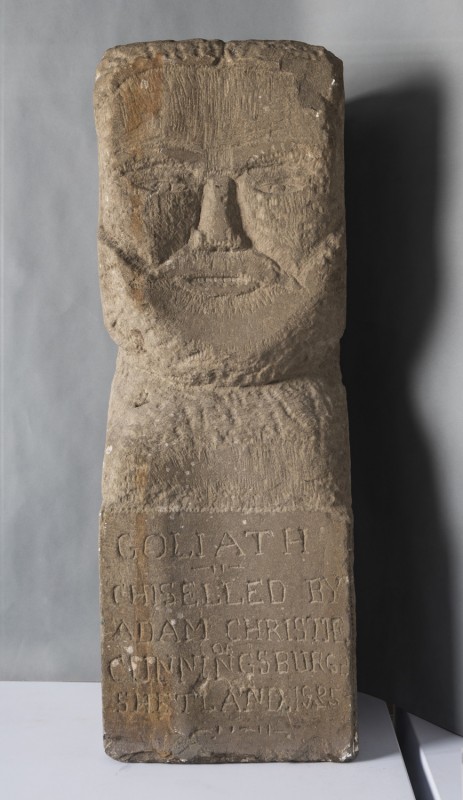

Adam Christie (1868–1950) was born in Shetland, and was a long-term resident at the Sunnyside Royal Hospital, formerly the Royal Asylum of Montrose, on the edge of the town. He was a writer and musician, and also a visual artist. He lived the majority of his life at Sunnyside, where he would spend his days carving found pieces of sandstone into faces and heads.

These lumps of stone became a vision of a person who Christie saw from his readings of the Bible and his knowledge of Celtic imagery. The heads were rough in formation, and they not only captured not only what he saw and felt, but also showed his passion and determination to make art from using his basic tools and skills.

Both artists suffered from some physical or mental disability in their early lives. Lamb, who was a lance corporal during the First World War, returned home with shrapnel in his right arm. This restricted his strength and movement but didn't stop him from continuing to sculpt.

Christie suffered from what we now understand as clinical depression. He was ferried many miles from his home to Montrose, but maintained his creative passion, and applied this to his daily routines and activities as a therapy for the condition and situation he found himself in.

Their lives were very different in terms of their upbringing and backgrounds. Lamb was formally educated in art – he made money from his artwork, and he had the crucial structure and environment of a dedicated studio, as well as specialist tools. He also had support and patronage from well-connected people locally to be commissioned to produce his sculptures.

Christie, on the other hand, had no formal art education and was forced into a life of confinement. He had to be creative to survive. He had no money, but produced his art through found materials, such as the sandstone remnants of a local bridge. His tools were pieces of thick glass and nails, making the task difficult and, no doubt, an act of hard labour.

The psychiatrist Kenneth Keddie, who worked at Sunnyside and wrote a book on Adam Christie, implies that the artist was the model for Lamb's sculpture The Daily News. Time must have been shared together in Lamb's studio so that he could capture the pose of the worn-out figure selling newspapers.

The sculpture is a modest-sized figure that closes in on itself as if protecting its identity. Its face under its hat and coat is barely recognisable, unlike the other Lamb portrait sculptures.

It was most likely that Lamb tried to help Christie with his working methods around this time, by suggesting he used 'proper tools' to sculpt with, as opposed to his basic ones. But Christie wasn't to be swayed and worked on with his own particular methods. Had he taken Lamb's advice, his sculptures could have been remarkably different in form and aesthetic.

While in Montrose, Lamb realised that there was a change in the arts happening on his doorstep, so he set out to capture a number of prominent writers, artists and poets, who were championing a new form of the arts for Scotland. Lamb was conveniently positioned to observe these people at close quarters.

Lamb's set of bronze busts from this period, just after the First World War, capture the moment of significance of his companions and sitters.

The writer Hugh MacDiarmid is flamboyantly seen as a bit of a wild-haired character, stern but full of fire; the artist Edward Baird seems cool, serious and determined.

The poet Violet Jacob is studious but creative and modern. He made them look like film stars.

Lamb continued his ability to gain creative opportunities at this time, and was commissioned in the early 1930s to sculpt a head-portrait of the young Princess Margaret.

His job entailed travelling to and working in London. He set up a studio in Piccadilly so that he could share time with the royals and be able to work directly from life.

As the work progressed, he was also commissioned to sculpt the young Elizabeth II – then Princess Elizabeth – and Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, then the Duchess of York. These three sculptures, which are relatively small, played a key part in Lamb's developing success and status.

His commissions were a success due to his skills and abilities to produce and manufacture the sculptures with reality, but also give an everydayness to the subjects. The princesses were young children at the time, and he was still relatively young himself, so the sculptures show a connection that would have been achieved between them.

In retrospect, these sculptures, which are currently housed in the William Lamb Studio in Montrose, show the females of the royals as a close family group. They are the familiar people we have seen in the royal family's private photographs and films.

Adam Christie's body of sculptures has over the years, in contrast, been difficult for public collections to identify and keep up to date. Some were even only recently discovered in gardens around the local area.

His sculptures have gained importance as they initially were identified as relating to Outsider Art. But over time this categorisation has become irrelevant, as his art is highly significant as a unique form of expression and creativity.

Christie's sculptures show someone developing forms of busts not directly from real people but from visions of his imagination; they were his versions of portraits. They came out of the stone from hard work. Some also have texts carved into the sculptures' bases, usually his name and the date, but mostly hidden from view.

The scale of Christie's sculptures was determined by the found stones. His largest known sculpture, Goliath, which is in the Shetland Museum collection, is a tall stone on its end.

This sculpture was bought for the collection in 1987 and makes a vital statement, not only as it celebrates an artist from Shetland, but it identifies his work as a key example of how creativity can maintain life whilst under duress. This work and his others held in public collections identify Christie as an important Scottish artist.

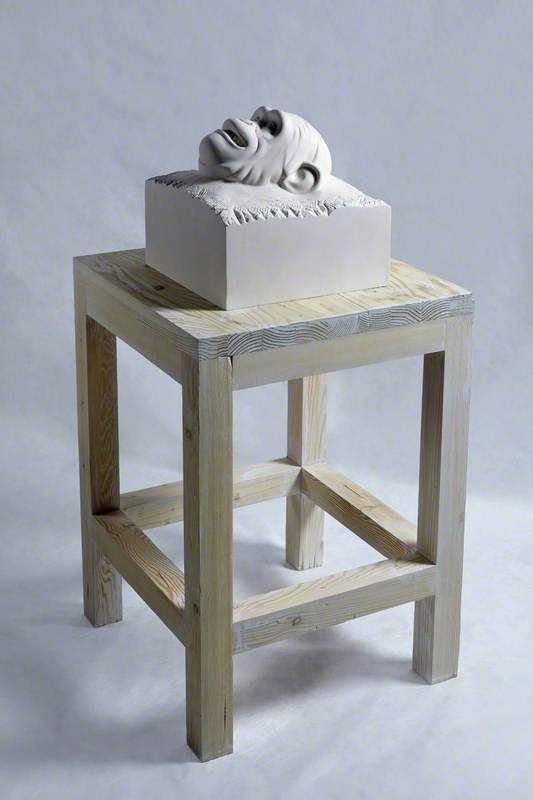

Adam Christie Memorial Stone

2016 by Brian Wyllie

Both artists found their final resting places in Sleepyhillock Cemetery, Montrose. Lamb's grave is marked by a grand Art Deco-style stone.

Christie was buried in a pauper's grave but, in 2016, his life was commemorated by a Historic Environment Scotland plaque and a sculpture by local artist Brian Wyllie placed in the cemetery.

These artists' self-determination to be creative against the odds and to identify the essential characteristics of people is still pertinent. Lamb's larger-than-life bronze statues, still to be seen around Montrose, are of key workers from his community – The Minesweeper, Bill the Smith and The Seafarer.

The Seaferer (The Trawl Hand)

1978

William Lamb (1893–1951) (posthumous cast)

These particular posthumous bronze castings of plaster originals give valid touchpoints for residents and visitors to the creative heritage that existed and still exists in the town. Contemporary sculptures by artists such as Kenny Hunter, Anne Davidson and Gillian Wearing continue to integrate public figurative sculpture into our communities with meaning.

Making these connections between Lamb and Christie shows us that art and creativity in life are crucial for our wellbeing. This interaction of like-minded artists, living and working in the same location, has positive effects, whether social or practical.

Lamb and Christie, although different in age, backgrounds and personal disabilities, had a mutual respect for each other. They benefited from sharing their lives and work, and are important documenters and visionaries of lives in sculpture, from their own chosen position.

Iain Irving, curator, producer and writer

This content was supported by Creative Scotland

Further reading

Kenneth Keddie, The Gentle Shetlander: The Extraordinary Story of an Artist in the Shadows, Paul Harris Publishing/The Shetland Times Ltd., 1984

John Stansfield, The People's Sculptor: The Life and Art of William Lamb ARSA (1893–1951), Birlinn, 2013