In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

Since the early 2000s, Ryan Gander has become one of the UK's most acclaimed contemporary artists. Based between Suffolk and London, he believes that the 'value in art is more closely linked to cause, idea and intent as opposed to appearance', thus his conceptual works – which are divergent but often minimalist in appearance – aim to make visible the invisible structures and systems of everyday life.

His practice cannot be anchored to one medium, although he consistently uses his artworks to articulate the busy workings of his imagination or his many logical ponderings about everyday life. By engaging the viewer cognitively with his enigmatic and sometimes cryptic works, he is nevertheless determined never to be 'didactic'. There should be no single interpretation of his work and he prefers to raise questions rather than answer them.

As part of Wild Eye, a public sculpture project in partnership with Invisible Dust, Yorkshire Wildlife Trust, Scarborough Borough Council and CaVCA, Gander's latest project We are only human (Incomplete sculpture for Scarborough to be finished by snow) is a conceptual response to the ongoing climate crisis and coastal erosion. Art UK spoke to the artist to find out more about the project.

Lydia Figes, Art UK: Can you tell me about how your recent project We are only human came about – and what it means when it is described as 'incomplete and to be finished by snow'?

Ryan Gander: When you say a sculpture is 'incomplete' people feel like they have been short-changed – or that I've stopped halfway through because I have a bad work ethic. The truth is that all really good artworks are the sum of their concise description. I've made artworks that are really hard to explain, and they don't travel very well verbally, in storytelling or rumour. The idea of an incomplete sculpture is a mystery, meaning there is a puzzle to solve. When you give all the answers it's not really art, it's just communication. Art is about all the missing pieces that people bring to it. I try to avoid didacticism. It's important to keep art open-ended and unpredictable.

The sculpture is on the headline, close to Scarborough Castle. It's high above the sea, on a peninsular. I went there when I was a child. It's so vast there it makes you feel entirely human, vulnerable and inconsequential. That struck me as interesting as we're living in the era of individuality, or having a 'unique selling point'. Everyone is thinking about how they're different. I feel that this way of thinking divides people – life is really about community, collectivity, collaboration and family. When you're in nature and you realise the vastness of it, it shocks you into realising that we're all ants. We only really work well together, not as individuals.

The work is an 'environmental work' but I'm not really an environmental artist or activist. For me, the work is more about a collision of the individual and the collective, that's the poetry of it. The work is a big concrete brutalist sculpture that takes the form of a piece of technology that stops coastal erosion by breaking waves. I treated it with an algorithm of snow and then subtracted the mass of the snow from the mass of the sculpture. So basically its original intention is to allow nature to interrupt us – rather than a human-designed sculpture that commands nature. This is the way it should be. We shouldn't be in control.

Lydia: You once said, 'the artwork should be like a gym for the imagination – and leave work for the viewer to do'. But there is something more direct and urgent about this work. It reminds us there may not be snow in the years to come. In the context of the climate crisis and creating work that engages with that, have you ever felt the need to create art that compels your audience into action?

Ryan: No, and I think that's the mistake of the environmental art movement. Environmental artists are often telling people what to do. In a museum or gallery, people don't want completion or things explained on a silver plate. They don't necessarily want all the answers. For example, in semiotics, humans are sceptical of conventional signs – a sign that is clearly authored and has a direct intention. Whereas if you're given a natural sign, like footsteps in the snow, you know it wasn't authored to teach you something. My take on art – but also an alternative 'environmentalism' – is that we should use natural semiotics to change cultural attitudes. People change by example, not by being told. The more you try to push people with didactic signs and instructions, the more resistant they will be.

On a personal level, I try to do my best. I have solar energy, I've installed a heat pump so we don't use oil or gas. I only drive electric cars, and reuse glass bottles from the milkman – this isn't being an 'eco-warrior'. It's just what should be normal. In this era of individuality, people love attention so they talk about these things more than they actually do them. In Britain, there's a stigma against environmentalism, in the same sense that there is a disregard towards the elitism of the art world. I reckon I've changed more people's attitudes just by driving an electric car than by making a sculpture. There are environmental artists that leave a huge carbon footprint by making their work.

I recently had the realisation that my child is going to be the generation that brags to younger kids that he once built a snowman in the garden because in 20 years Suffolk will have the climate of Barcelona – so it won't snow. It's a heartbreaking reality, that translates the gravity of the situation.

Lydia: The materials used in this project have been sustainably sourced, or from industrial waste. How did you go about this?

Ryan: I used a low-carbon concrete that requires 85% less carbon than standard concrete. This particular concrete is made from otherwise wasted industrial products and recycled glass, but also limestone, skeletons and shells of prehistoric sea life. The material is conceptual as it relates back to the sea, which it is trying to interrupt.

Lydia: The work is called We are only human, which I read as a statement about our fallibility, or on the other hand, perhaps a reminder that there is only so much an individual can do in relation to the climate crisis. How did this title capture the project for you?

Ryan: Yes, that we're fragile. I don't want to be like a messiah, nor even an environmental artist. We are only human is about saying everyone can do what they can when they can – until it becomes normal practice.

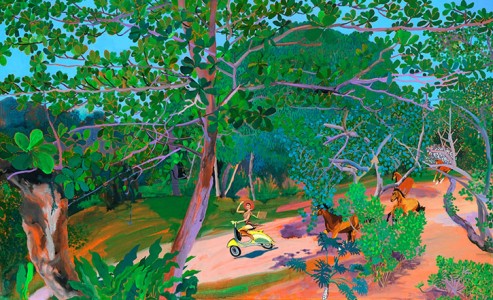

The Green and The Gardens

2019

Ryan Gander (b.1976) and Gillespies

Lydia: Other outdoor sculptural works you have made compel the viewer to reconsider what is around them. The Green and The Gardens (2019) in Cambridge comprises five fibreglass tents that illuminate at night. How did this project come about?

Ryan: I think all good art is about making visible the things that are usually invisible to us. The artwork comprises sculptures of tents that appear to be hyperrealistic. They glow at night and are illuminated from within so that it looks like people are camping. There are a lot of them in a public green, surrounded by a medical campus. The idea was that patients would look out the window and think these tents were from scouts or a festival. The tents aren't the art – it's really the invisible systems that they draw our attention to. By that I mean, when we see grass it invokes a number of associations, for example, we could see a campsite, a village green, a football field, farmland, a pub.

The Green and The Gardens

2019

Ryan Gander (b.1976) and Gillespies

I saw this work as a form of escapism – for the imagination. If I was in hospital and looking down, I'd want to see something that offers diverse nostalgic memories. There's a certain romance to camping, or the traditional British village green with deck chairs, knotted hankies, ice cream, fishing in the pond – a sort of Enid Blyton world that's cliché but also a nice fiction about Britain. More generally, tents are a great vehicle to project yourself into, and these ones appear particularly warm and inviting. For me, the quality of an artwork is how many readings can be taken from it.

Lydia: Do you have any daily rituals or studio practices that might surprise people?

Ryan: My dad worked in a repetitive job in industry. He always told me 'if you do a job that you love, and a job that's different every day – you never have to work a day in your life.' I do have things I repetitively do, but not every day. The big objective is the opposite – to make sure I'm never doing the same thing.

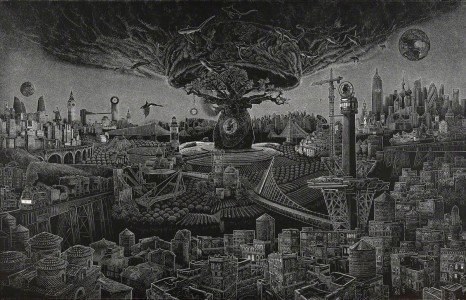

The biggest and weirdest ritual I have that surprises people is probably my studio and office. There's a very elaborate and enormous filing system of creative ideas that looks a bit like that basement scene in the Hannibal Lecter show. I think people are most shocked about that as it's exceptionally organised.

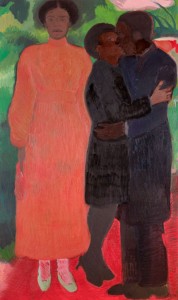

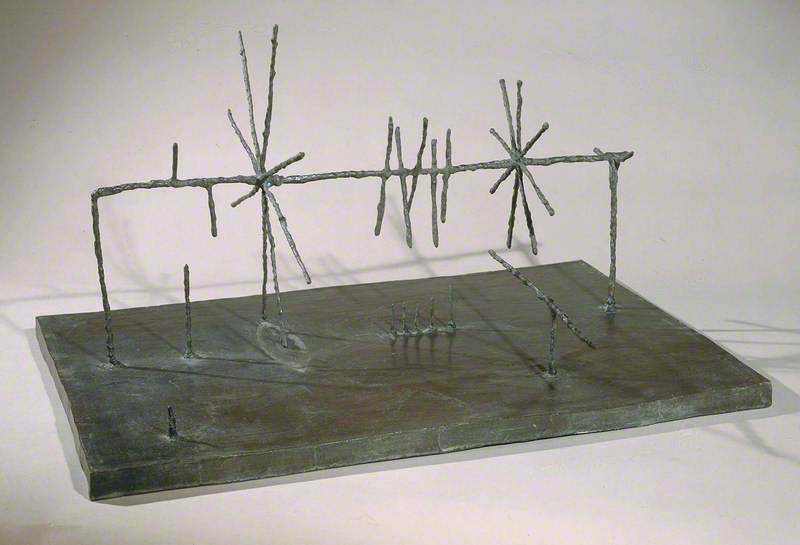

As Old as Time Itself, Slept Alone

2016

Ryan Gander (b.1976)

Lydia: If you could give your much younger, 'pre-success self' advice, what would you say?

Ryan: That your popularity and the amount that people appreciate you will peak and trough. Sometimes you'll be a millionaire, and sometimes you'll be skint, don't worry about it.

I got a lot of attention and made a lot of money from art when I was young, but it hasn't stayed consistent. The world changes really quickly, and the things that people appreciate change too. You either change with it, or you just wait and believe in what you're doing.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK