In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

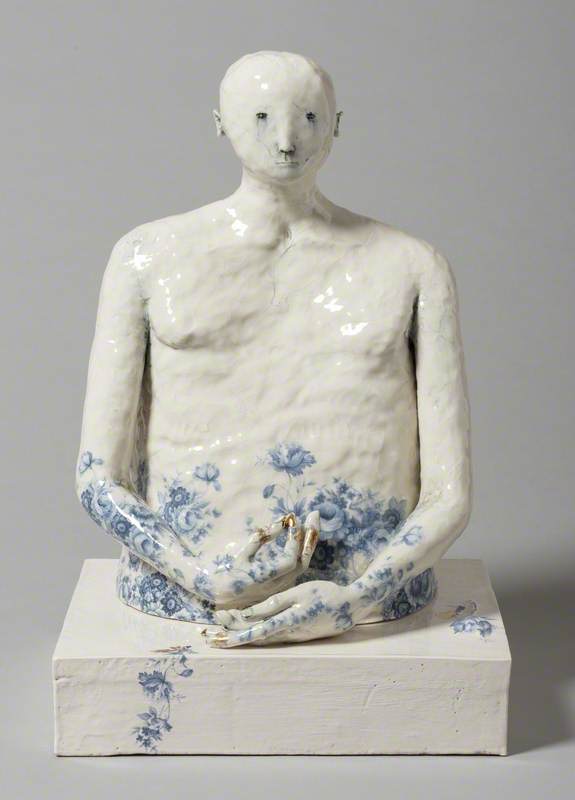

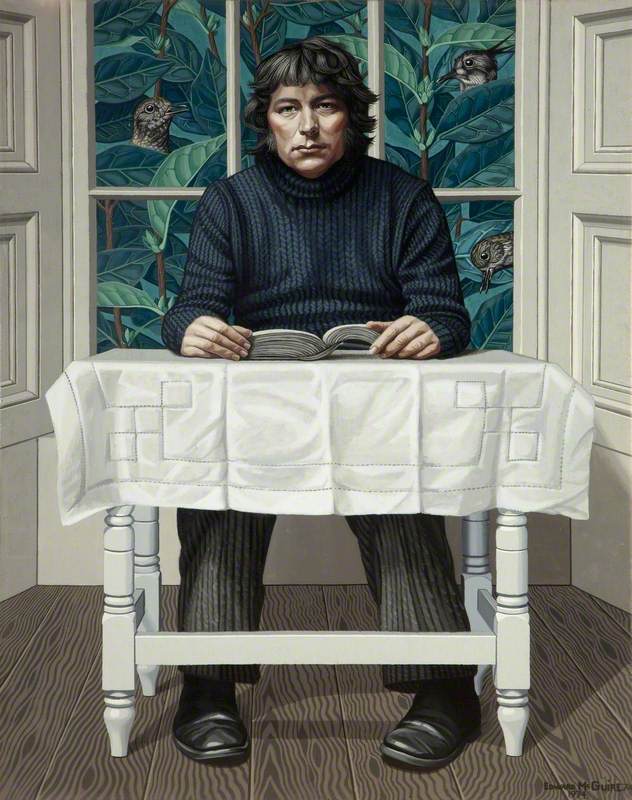

Claire Curneen is a Wales-based Irish artist, educated at Cork, Belfast and Cardiff. Her figurative sculptures in porcelain, terracotta and black stoneware use the fragile language of ceramics to explore the vulnerability, pathos and resilience of the human condition. Drawing on Catholic imagery and ancient mythology, her narratives are subtle, enigmatic and affecting. I talked to Claire in her studio in the Splott district of Cardiff.

© the artist. Image credit: Aberystwyth University School of Art Museum and Galleries

Claire Curneen (b.1968)

Aberystwyth University School of Art Museum and GalleriesAndrew Renton: As a sculptor why did you choose ceramics as your preferred medium?

Claire Curneen: It's not that I really wanted to do ceramics – I made something in clay and a tutor said it was good. Ceramics is more modest as well. When I was a student, the sculpture department was far too macho and intimidating. The things I make are sculpture, backed up by sculpture and painting, but also by studio ceramics and the history of ceramics. It's no coincidence that we see clay used a lot within fine art now. It makes a direct link to the outsider, the night-class maker, and the intimacy of making things in clay. It doesn't come with the hierarchy or the baggage.

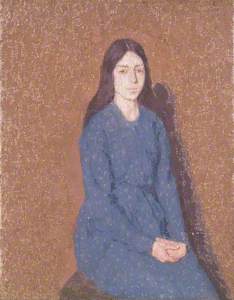

Andrew: Before making Blue Series, you studied Gwen John's Girl in a Blue Dress (below) but also historic Welsh ceramics. You also added transfer-printed flowers and gold lustre to the piece. How strongly does ceramic tradition underpin your work?

Claire: It's important because you only understand the figures through their materials. If that figure was a bronze, it wouldn't be the same. I'm interested in ceramic language because I'm trained and know what to do with it. The way I make something is so important. I make it like I make a pot and can't make it any other way. I started to look at blue transfers and ceramic printing, but they were just ways to get a good surface.

Andrew: Gwen John was intensely interested in Catholicism. You say you're not religious yourself but seem to have an affection for religion. Did you feel a sense of identity or empathy with her?

Claire: It wasn't something I consciously knew, but could tell almost by how she painted the presence of somebody. You can spend a lot of time watching a Gwen John girl with her hands crossed, just sitting. The artist or the nun or the monk, they're similar kinds of activities, not unlike coming to my studio every day. Having St Alban's church out there – I don't really go but I want people to go there, be devout, do whatever I don't do.

Image credit: Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

Girl in a Blue Dress probably 1914–1915

Gwen John (1876–1939)

Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum WalesI remember my childhood, everybody going to Mass on Sunday. As a teenager, you got to go with your friends and it became a social thing. You got further back in the church so you could exit quickly before Communion. That's what I got tired of, but I'm moved by it. I did go to St Alban's last Easter, at the back of the church, like I'm committing but not committing. They were doing the Stations of the Cross and it was much more formal than anything I'd known in Ireland. It meant so much to them, and it means a very different thing to me. I'm not religious but I float around faith.

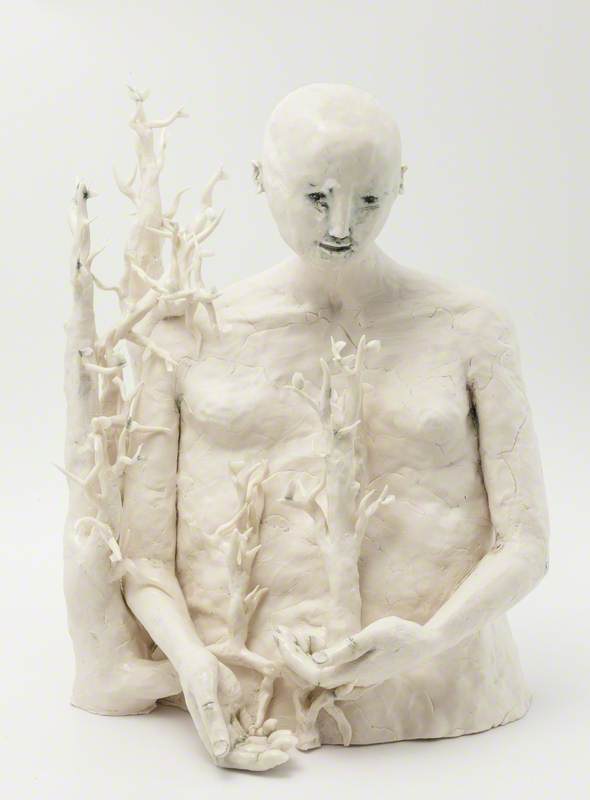

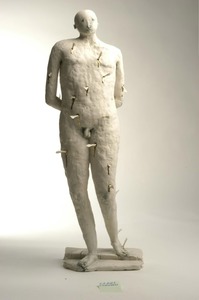

Andrew: Can you talk about Touched, commissioned for Amgueddfa Cymru in 2015? This black figure has a superstructure of branches on its head. You took a hammer to an earlier porcelain figure and tied fragments to the branches with red thread, alluding to an Irish folk tradition.

Claire: Tying offerings to trees at healing places is a tradition in Ireland as well as Wales and Scotland. 'Clootie trees' generally grow near a well or water. It's a kind of pilgrimage and becomes this thing that seems to save everybody from everything – but it doesn't!

Touched was challenging to make. The figure and the branches, the connection to ceremony and tokens. I loved making that piece. The dense bog-like black clay felt very much dug from the ground, almost like the bog man in Seamus Heaney's The Tollund Man, and contrasts with the translucency of the broken porcelain fingers tied on. You only really see them when you get quite close. They might seem a little alarming, but the act of the binding makes it all seem alright.

When I make something, time's very important. With Touched, there's so much time in the thing that was made and broken and didn't quite work. I didn't mind smashing up something I'd already made, because it was reclaiming something – making something new. It was liberating. I enjoy that there was alarm from somebody going, 'Aah! You can't do that!' I said, 'Yes, I can! It's easy!'

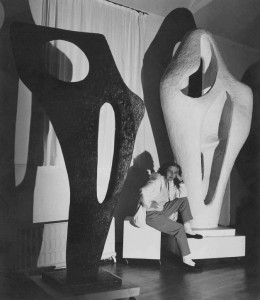

Image credit: Dewi Tannat Lloyd

Claire Curneen in her Cardiff studio

Andrew: What inspired you to explore using thread, whether binding things or this cascade of red thread in the studio?

Claire: I did an exhibition with textile artist Alice Kettle and we had a very good connection. When you wrap things up, you hide something but you might care for something or heal something. The red column, I look at it and think of things inside it. What it does is make my work bigger. I sometimes have it like a length attached to a figure, and suddenly the piece is ten times the size.

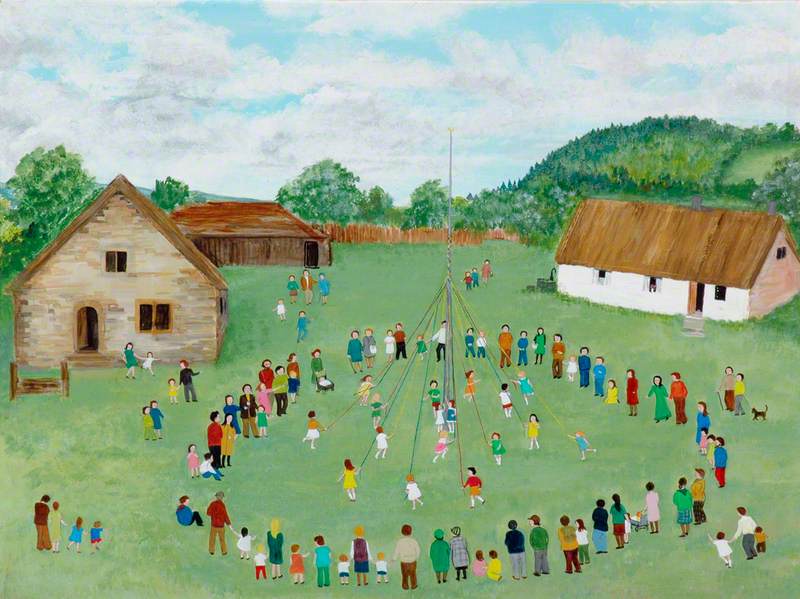

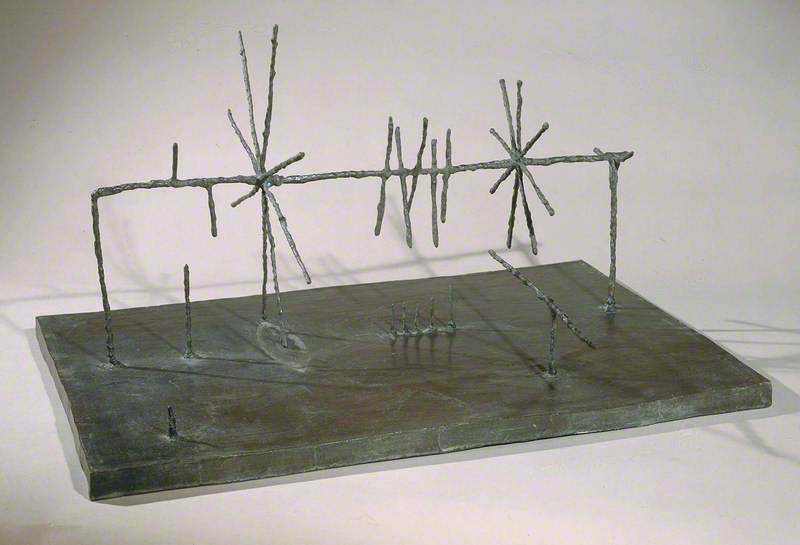

Working in parts, like with Tending the Fires and Baroque and Beserk, is a really good way to deal with scale but not lose the sensibility of something small. They capture that sense of time and intimacy and delicacy, and porcelain quality as well, but giving it more theatre. You can't rest. It's an event, isn't it? An eruption.

© the artist. Image credit: Gareth Jones

'Baroque and Beserk' at Walker Art Gallery

2017, porcelain by Claire Curneen (b.1968)

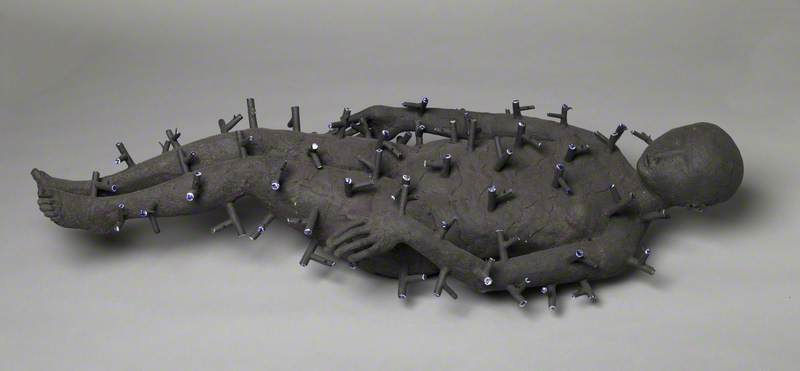

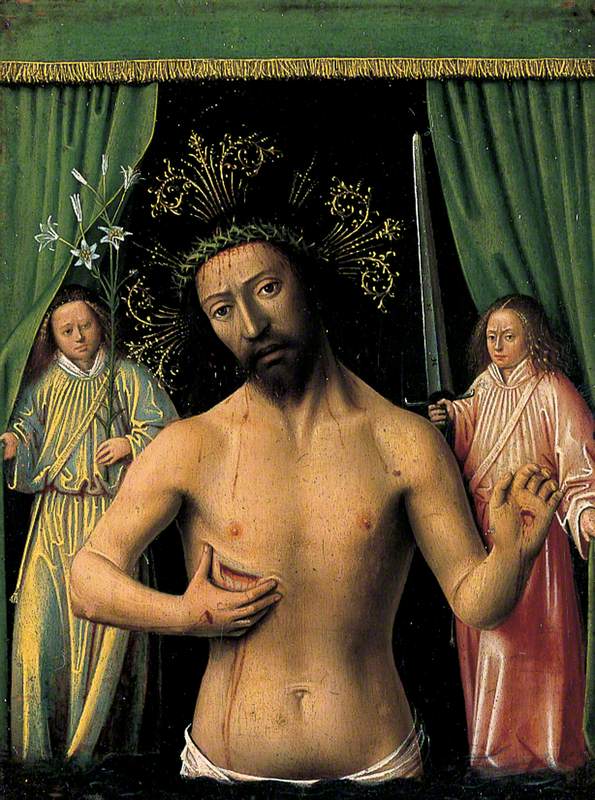

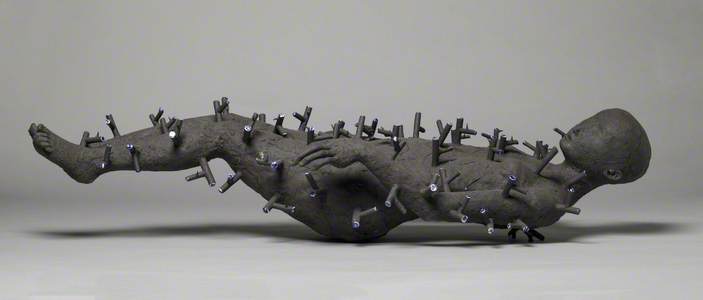

Andrew: Your figures – like Saint Sebastian or Daphne – are often about trauma and martyrdom and the pain these individuals have been through, but you don't express the trauma so much as surviving the trauma and somehow being at peace with it. Is this a way of showing compassion or admiration for how people handle suffering?

Claire: When I think of what drew me to these subjects in the first instance, looking at the Stations, seeing how the body falls, like the Christ figure, or the crowning with thorns or this suffering body, it makes you wince a bit. But looking at Renaissance works of Saint Sebastian, he's always portrayed in that martyred way, going beyond the trauma. I find that incredible, just witnessing it but also how people do that.

© the artist. Image credit: Aberystwyth University School of Art Museum and Galleries

Claire Curneen (b.1968)

Aberystwyth University School of Art Museum and Galleries

I haven't suffered trauma. There's a sense from the things I've made that I must feel that or have experienced that, when I haven't. It's not about actually experiencing for me. It's being able to observe a kind of suffering. You can see it if you sit on the bus and watch somebody: you know when somebody's having a tough time. It's fleeting as well. I'm often quoting these grand figures but they're about something quite familiar and close to us that we just walk by.

The figures I make also give that sense of something about to happen, like spring or things about to give birth. There's always a kind of pathos with that – you know we're going to lose it. The things I make are like memorials, like little memories of things.

Andrew: How do you feel about showing your work in religious spaces?

Claire: Religious spaces are beautiful but a lot to compete with. You're almost overwhelmed by the architecture, although tiny things can be like giant things. In 1999 to 2000 I did a residency at Crawford Arts Centre, near the old cathedral of St Andrews. I placed a figure in the ruins. I didn't ask, just put it under my arm and brought it with me, like a private devotion. Sometimes I find it difficult to say what they are – the things that I make – except, having a conversation like this, suddenly I know: 'private devotion – maybe that's what they are!'

View this post on Instagram

Andrew Renton, curator and ceramics researcher

This content was supported by Welsh Government funding

Claire Curneen is developing a project with James Freeman Gallery at St Bartholomew the Great, London for 2025