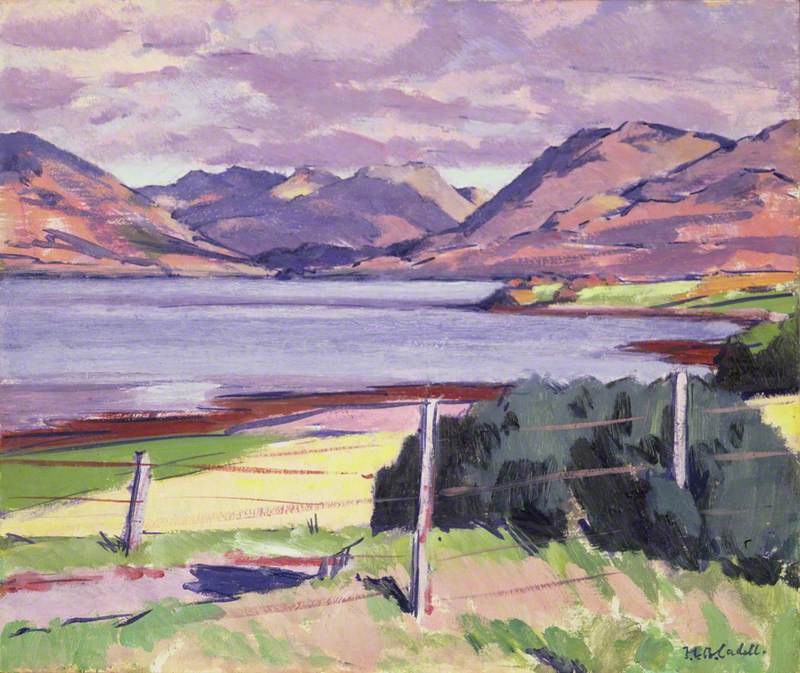

Flow Country is a shimmering expanse of blanket bog in the far north of Scotland, a world of mirrored water and sky, purple and orange peatland. As well as being an important carbon sink, it's a spectacular location for photography.

This is the territory to which Zimbabwean-Scottish artist Sekai Machache travelled to create her 2021 series The Divine Sky – a film with five accompanying stills – wearing Blue of the Horizon, an indigo marbled dress with trailing train, created in collaboration with artist and seamstress Fiona Catherine Powell.

The work traverses night and day, the artist positioned between pools of water, on a tufted meadow of grass, in poses suggesting meditative alertness or ritual invocation. In some images, she appears draped in plumes of smoke. The indigo patterning of the robe – developed out of a process of automatic drawing or mark-making – seems to acquire symbolic potency in this setting, as if the garment represented a point of interchange or translation between the visual grammars of sea and sky.

The relationship between these two tracts of blue is, in fact, a central metaphor within the work. The artist refers to 'tracing the language of water' through performance and gesture – as if dance and trance could transform the body into a vessel for travelling between the two realms, and in turn between different imaginative spaces.

Visually, Light/Deep Divine Sky is stunning, its rich blue colour palette – echoed in a series of studio-based works using a marbled disc and back-cloth – typical of the artist's engagement with a particular hue or tonal contrast for each of her projects.

These colour schemes tend to be layered with cultural symbolism as well as being sensorily appealing, as the artist explained in an interview with Katherine Ka Yi Liu, who curated Machache's 2020 show 'The Divine Sky' (including earlier pieces from the same project) at Glasgow's House for an Art Lover.

'In ..."The Divine Sky", my selected colour is blue. I'm really interested in the ancient indigo dyeing processes across West Africa. There are 12 stages in the indigo dyeing process of Mali and the darkest blues that can be produced are called The Divine Sky.'

Writing about a later iteration of the show, 'Divine Sky', presented at the photography gallery Stills in Edinburgh in 2021, Machache described her colour scheme as also being a reference to Blue Willow chinaware, a familiar style of decorative crockery with origins in Tang Dynasty China but commodified and circulated endlessly in knock-off forms in the west.

In Profound Divine Sky, the central film-piece in Light/Deep Divine Sky, the artist carries a patterned blue vase of Blue Willow design, as if blue were a portal to histories of colonial trade, exploitation and cultural appropriation.

As these complex symbologies suggest, Light/Deep Divine Sky resonates with a range of cultural concerns and art-historical contexts, from Afro-Futurism to ecological breakdown, slavery, colonialism and even the racial profile of rural Scotland – it is still a jolt to see minoritised bodies in landscapes like these.

The voice-over that accompanies Profound Divine Sky brings many of these themes to the surface while also indicating the self-conscious mysticism of Machache's storytelling: 'the earth buzzes with a blue frequency channelled directly from Sirius, the black star portal that our ancestors travelled here through…We are in the process of healing ancient wounds, created by the original crime that set this world adrift. The red frequency that our planet has been emanating is being healed.'

The impression here is of trauma being worked through on a subliminal level, one that could be broached either in psychological or spiritual terms. The language is indicative of a new generation of creatives – poets, painters – for whom elements of folklore, animism and occultism have been embraced both as creative tools – in particular as points of access to supposed ancestral belief or kinship – and in defiance of enlightenment rationalism, with all its blind-spots and prejudices, many of them racial or gendered.

Again, Machache's interview with Ka Yi Liu provides illuminating context for the work that narratives such as the above are doing: 'I think that we often subconsciously hold within us certain stories. These stories that we tell ourselves about ourselves become our "origin stories", which in turn often become our core beliefs that form an idea of who we are. I think that as artists we have the space to consciously create new narratives that can potentially catalyse a process of healing.'

The artist's own story begins in 1989 in Harare, Zimbabwe. Relocating to Scotland aged four, she graduated from Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art in Dundee in 2012, but now lives and works in Glasgow.

The photographer and filmmaker's work has become more visible over the last few years through a series of residencies and solo shows, with Edinburgh Art Festival providing a multi-faceted platform during the summer of 2021. Divine Sky ran at Stills as part of their Projects 20 series supporting emerging artists, while the film Hypnagogia Glossolalia was included in the Fringe of Colour Films showcase.

Machache also appeared in the RESET programme produced by artist Alberta Whittle for Jupiter Artland. This involved participation in Whittle's multi-contributor film-piece, with works exhibited alongside those of Whittle's nine other 'accomplices' at the gallery and sculpture park from July to October.

At Street Level Photoworks in Glasgow earlier in the year, Machache collaborated with Kenyan artist Awuor Onyango on 'Body of Land: Ritual Manifestation', part of Glasgow International. For that show, a gloomy, sultry colour palette was favoured over the bright azure of The Divine Sky, with bodies dressed in red or daubed with white pigment emerging from pitch-black backgrounds.

At once potent and intangible presences, these figures were accompanied by a set of marbled ink drawings. Similarly, a set of blue ink drawings provided the basis for the visual patterning of the robe in The Divine Sky. The three 'theme colours' of that show, red white and black, 'each ... represent[ed] an aspect of the self/soul', as explained to Ka Yi Liu.

'This is derived from a concept that you find in many cultures including the Luo tribe from western Kenya, who believe that the human soul is split into three. This concept is comparable in my understanding to Freud's concept of the mind which is split into the id, ego and superego. Another example could be the three gunas in Hinduism. I try to find connections and/or similarities across cultures and describe them through my images.'

While Machache's practice emerges from a sometimes esoteric philosophical space, it appeals first and foremost in sensory and emotional terms, transporting us to a place of beauty and mystery. These newly acquired works are a valuable contribution to The Fleming Collection, indicating the imaginative, spiritual and cultural breadth of Scottish art at the start of the 2020s.

Greg Thomas, writer and editor

A version of this article was originally published by The Fleming Collection