A new podcast series — Sculpting Lives — written and presented by Dr Sarah Victoria Turner (Deputy Director, Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art) and Jo Baring (Director, The Ingram Collection) explores the lives and careers of a number of women who contributed in groundbreaking ways to the histories of sculpture and art.

Each episode takes a woman sculptor as its subject, exploring the artworks, networks, connections and relationships of these artists. Sculpting Lives includes new interviews with curators, friends, family and the artists themselves, and is recorded in places that are significant for these women — their studios, as well as galleries and public places where their work is on display.

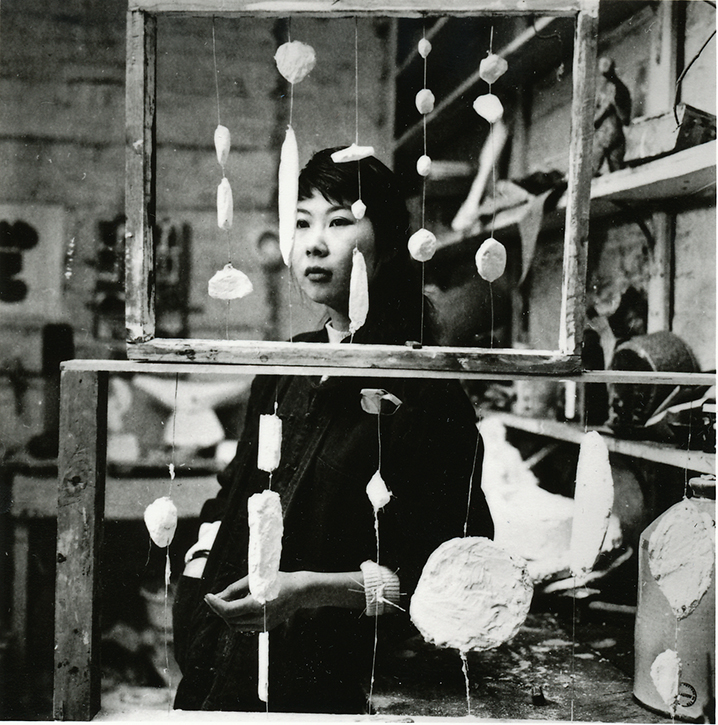

'Being female and foreign was never a problem as a student, later I realised that there was a difference, but what was important in the end was what I did and not where I came from. Race and gender were givens I worked from, perhaps the work does reflect this which is fine, but I did not want to make them an issue.' – Kim Lim

'She never wanted to be perceived as being 'other' just because she was a woman and foreign.' – Bianca Chu, Deputy Director, Sotheby's S2

There are over eighty works by the sculptor Kim Lim in public collections in the UK (over the coming year more will be added to the Art UK website), yet many people will be unfamiliar with her work or may not have heard her name before. There is only one other artist of Asian heritage who has more works in British public collections than Lim, the sculptor Anish Kapoor. With such a significant body of work, and much of it in our public collections, Kim Lim undoubtedly deserves to be more prominently featured in the histories of British art.

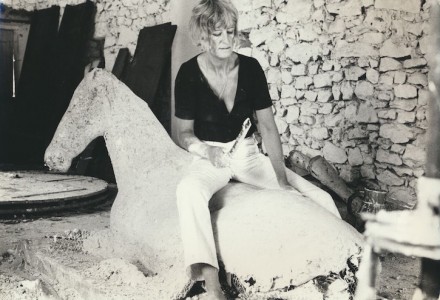

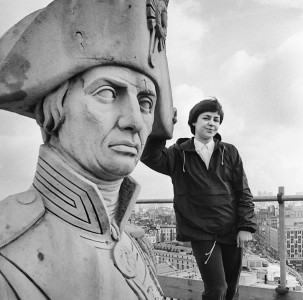

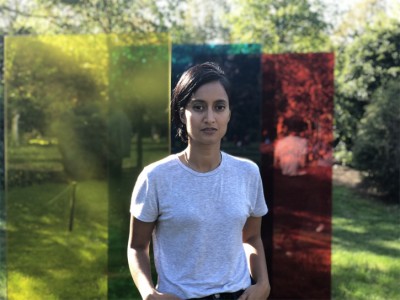

Image credit: courtesy of the artist's estate

Kim Lim in her studio, 1959

In this episode of Sculpting Lives, we explore the factors involved in the making of an artist's reputation, both during their lifetime and after their death. Did the medium in which Lim worked — sculpture — play a part in her not being as well known as other artists of her generation? And what significance did her gender and her race have on the way she has been positioned in the art world? As the statement above makes clear, Lim was wary about being pigeonholed as 'female' and 'foreign' — like many artists of her generation, she resisted being described in terms that anchored her artworks too securely to her biography or ethnicity.

Lim demonstrated great ambition and determination from an early age, working against the conventional expectations of her family to become an artist. She was born into a wealthy Chinese family in Singapore in 1936 but left at the young age of 17 to enrol at St Martin's School of Art in London where she was taught by the sculptor Anthony Caro from 1954 to 1956. She then moved to the Slade School of Art, graduating in 1960. This was a period of tremendous change in the British art world. Times were still incredibly hard financially as the country struggled with austerity after the Second World War but, gradually, more private galleries opened and an increasing number of students from the UK and abroad were attracted to enrol in art school, imagining future careers as artists and art teachers.

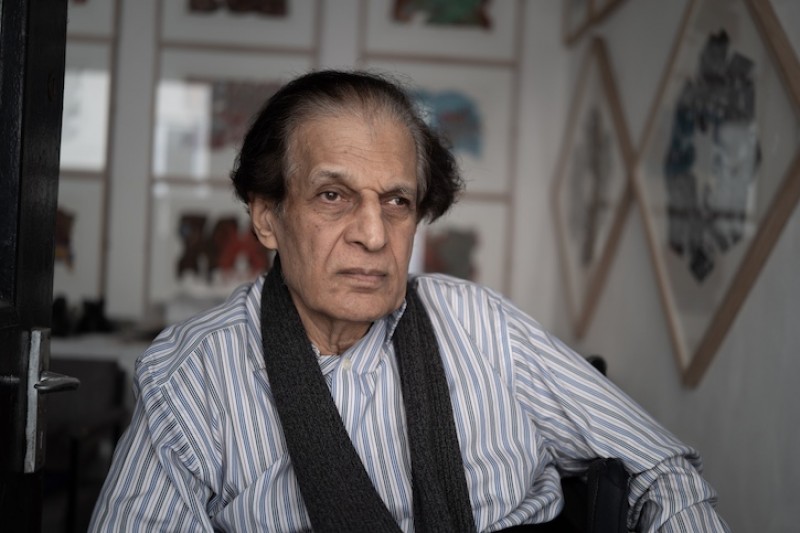

In 1960, Lim married the sculptor William Turnbull. Theirs was a creative partnership which lasted until Lim's death in 1997. In this episode, we conducted an in-depth and candid interview with one of Lim and Turnbull's sons, Alex Turnbull, to examine the role that a family has in preserving and promoting the career and reputation of someone so close. Surrounded by the works of both his parents, we discussed how Lim had to adapt to working from home and looking after her family, often making sculpture in the garden.

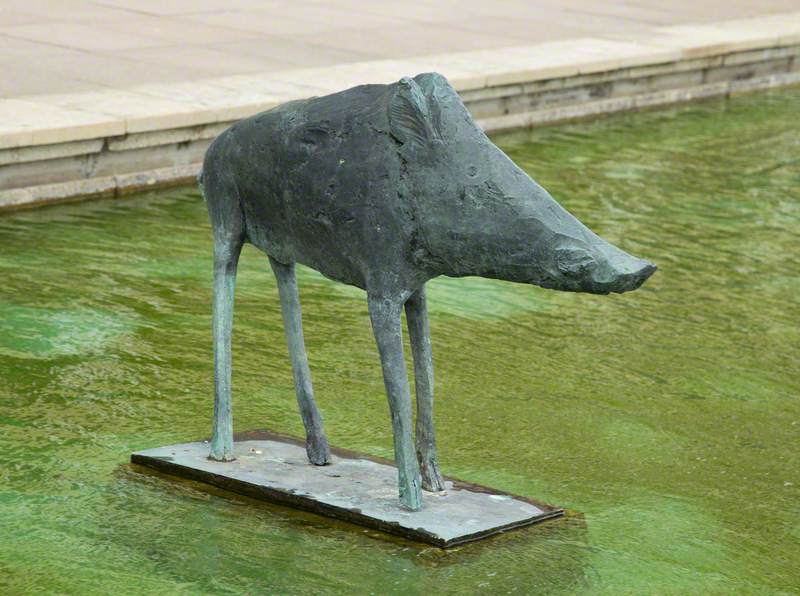

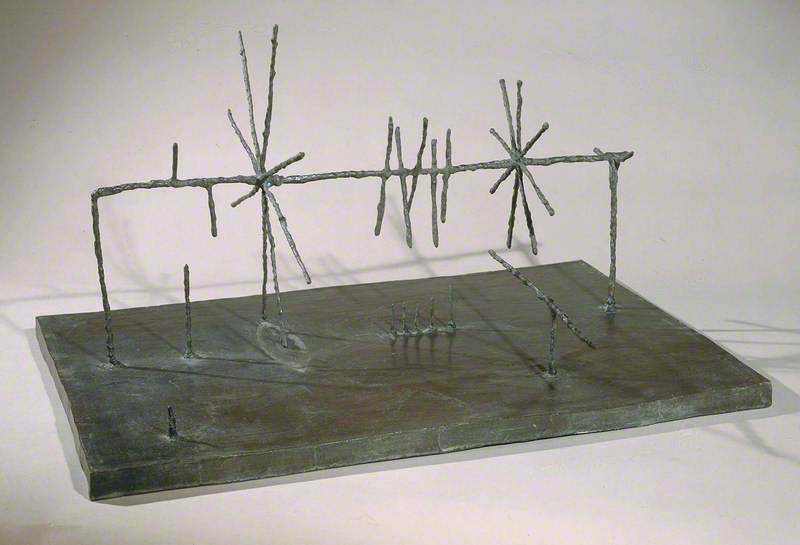

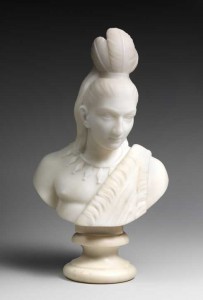

Lim was committed to the concept of 'truth to materials'. In an early work, Samurai (1961, Arts Council Collection), it is clear to see how Lim let the formal and physical qualities of the wood she was working with speak for itself. She uses the cracks and grains of the natural material, enhancing rather than hiding them, in this sculpture of stacked forms. Her admiration of the Romanian-born sculptor Constantin Brâncuși is also clearly apparent here. Lim travelled widely with her husband, collecting images of sculpture, past and present, which she would pin to the walls of her studio when she returned home to fire her imagination.

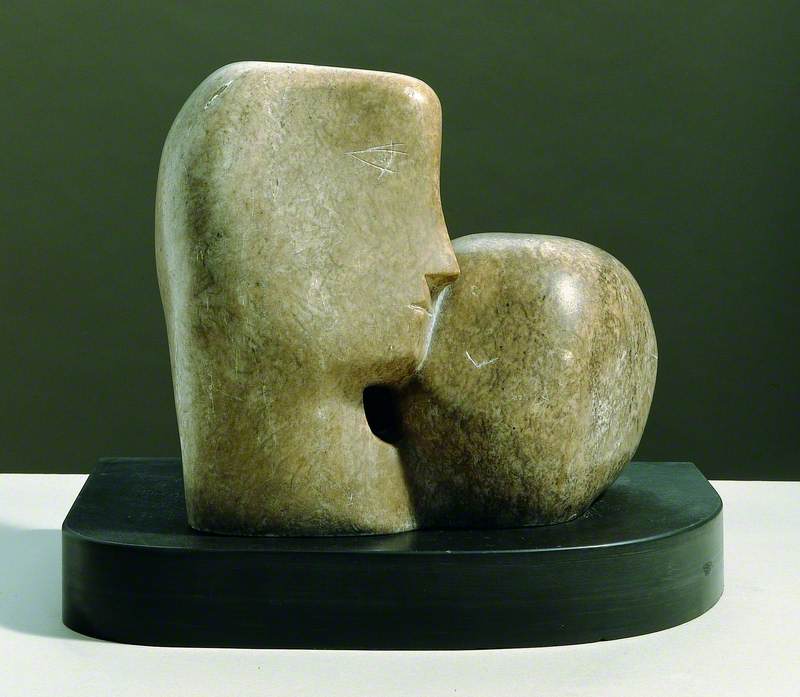

After working predominantly with wood in the early part of her career, Lim began to use stone in 1980. Again, she worked with, rather than against, this hard, obdurate material. Trace II (1982, Arts Council Collection) demonstrates how she was able to introduce rhythm and lightness into her structures through the use of curving, sensuous lines that she carved into stone surfaces. With Bianca Chu, Deputy Director of Sotheby's S2 and curator of recent exhibitions of Lim's work, we discussed how Lim developed her artistic language of form, space, rhythm and light. Lim was also an accomplished printmaker and drew on the lessons she had learnt through etching and other print techniques about the importance of balancing lines within a composition when making her sculptural work of both incredible serenity and energy.

Over twenty years after her death, Kim Lim's reputation is definitely rising. This is largely due to a number of recent presentations of her work in group and solo shows, with accompanying catalogues and reviews. Listen to the Sculpting Lives episode on Kim Lim to find out why anyone interested in sculpture needs to know more about her work. She is, in the words of our interviewee Bianca Chu, an artist 'in her own orbit'.

Jo Baring, Director of The Ingram Collection of Modern and Contemporary British Art, and Sarah Turner, Deputy Director for Research at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art

Find the Sculpting Lives podcast on Audioboom where you'll find listening options, and follow the podcast on Instagram

Sculpting Lives podcast