The cultural landscape of post-1945 Britain was diverse and busy. As 'war artists' returned to more familiar subject matter, magazines and journals reproduced and reviewed their new works.

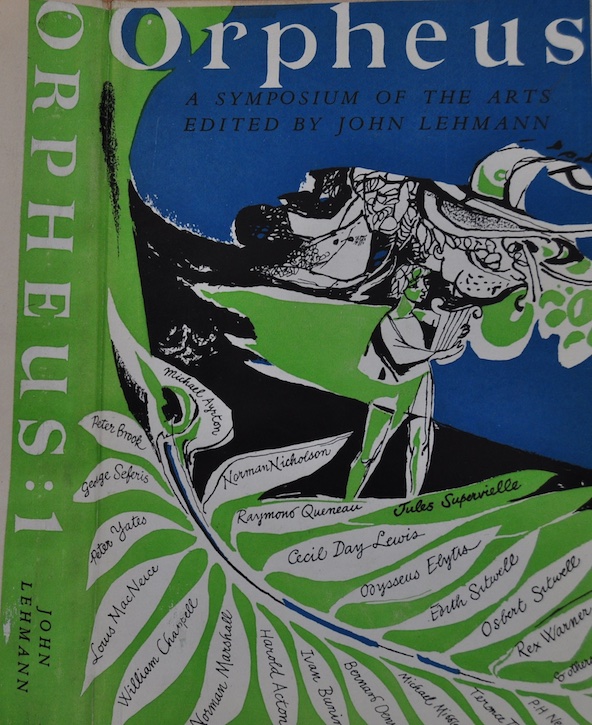

Launched in 1948, John Lehmann's Orpheus: A Symposium of the Arts showcased the Neo-Romantic painters, whose often melancholy works reflected their profound emotional relationship with their physical surroundings. While the publication itself was short-lived it nonetheless gave a timely boost to a movement whose stock would rise further in the years that followed.

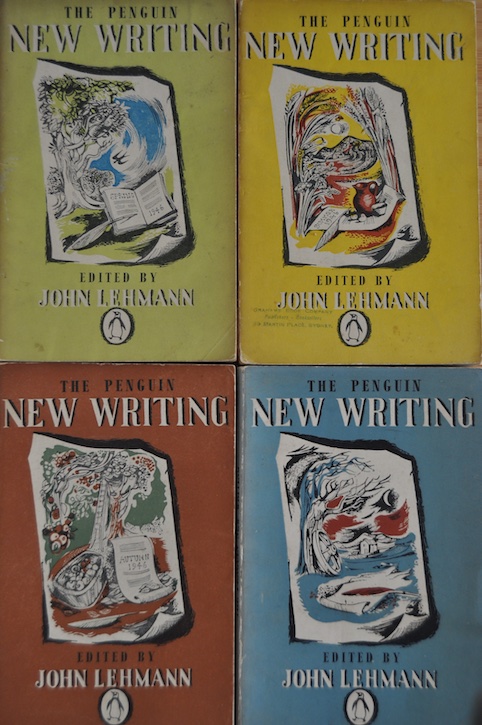

A partner in Leonard and Virginia Woolf's Hogarth Press, Lehmann launched an affordable monthly literary magazine, The Penguin New Writing, in 1940. This was devoted to fiction, poetry and reportage, particularly addressing civilian life on the 'home front' and the experiences of combatants overseas. Lehmann was keen, however, that it should also feature images of paintings at a time when it was often hard for the public to encounter art in person.

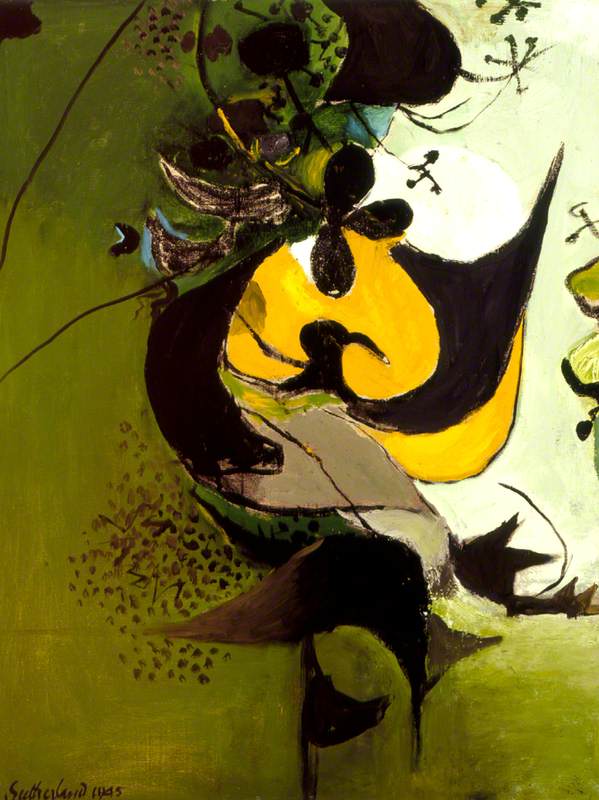

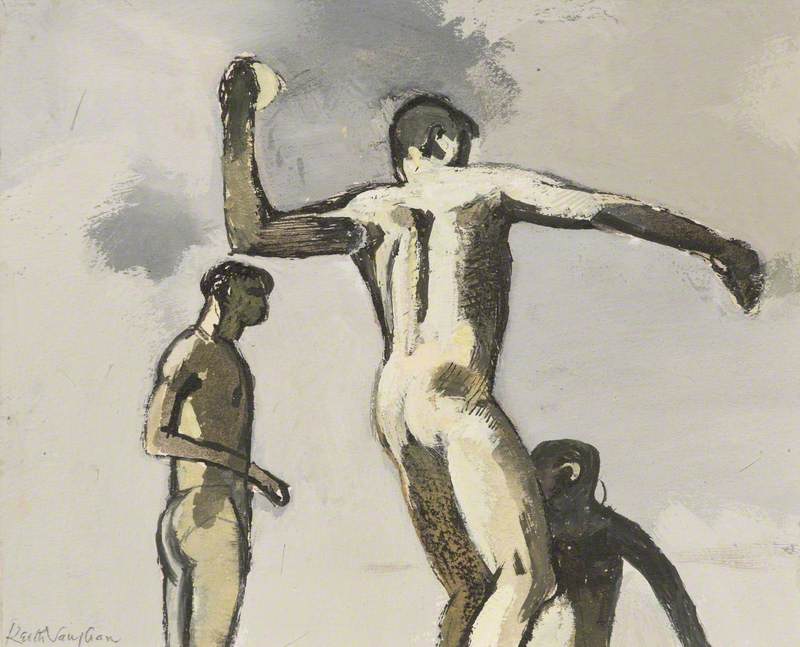

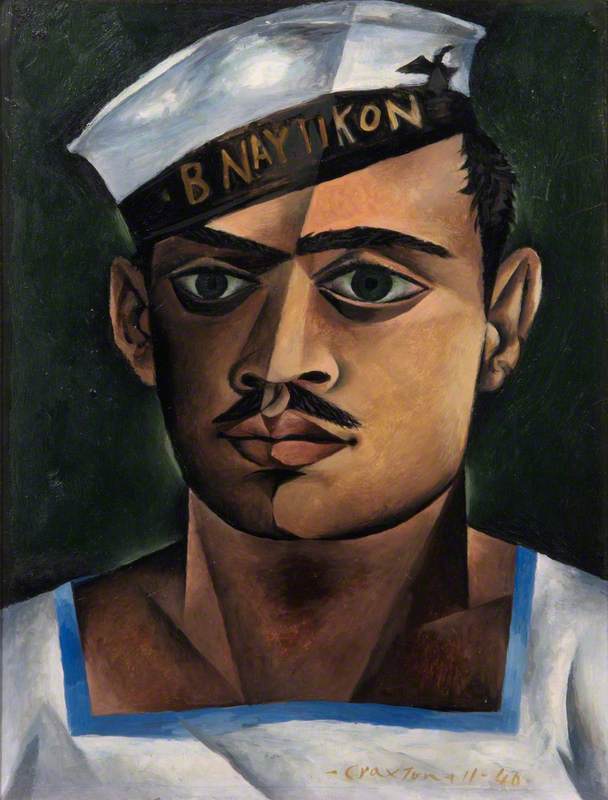

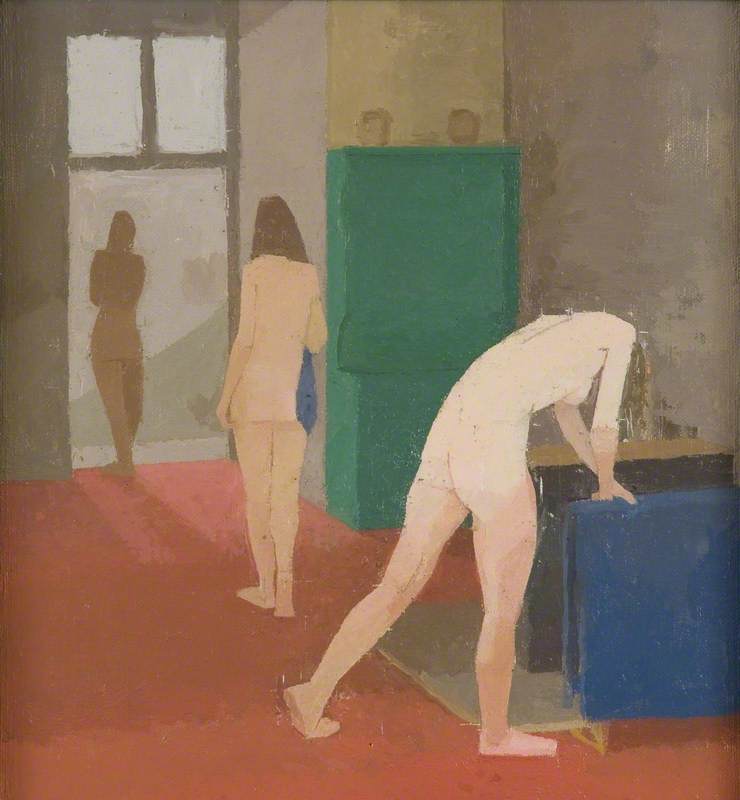

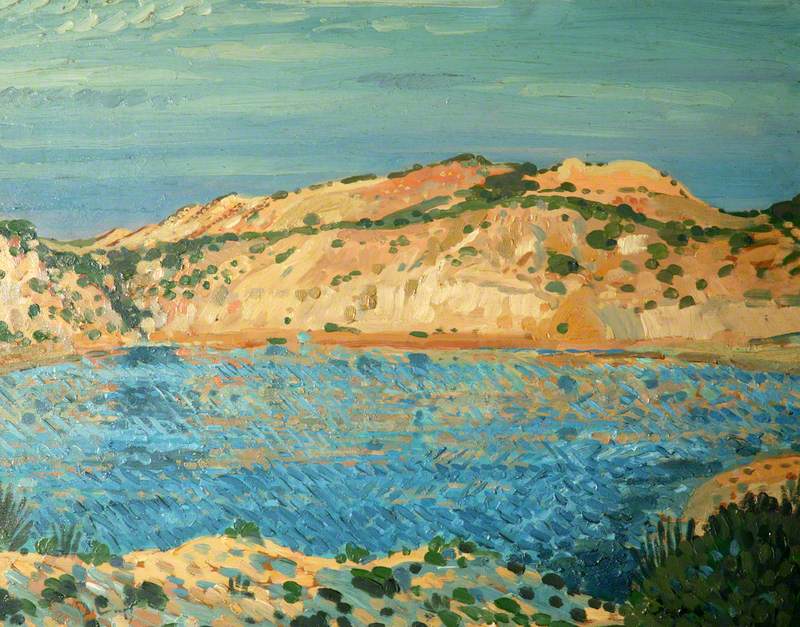

Accordingly, the Neo-Romantic painter Keith Vaughan, then serving in the Non-Combatant Corps, had three drawings of life in a military camp included in the June 1942 issue. Subsequent months saw black and white photogravure reproductions of work from John Piper, Graham Sutherland and Edward Burra. In March 1945, Lehmann was able to include colour reproductions of paintings – by Derek Hill and John Craxton – for the first time. Work by John Minton – including his Corsican Landscape – Victor Pasmore and Michael Ayrton followed, as did articles on theatre, ballet and cinema.

With a peak monthly wartime circulation of nearly 100,000, The Penguin New Writing appeared less frequently as its readership began to fall off in the post-war period, and it ceased publication in 1950. The change to a quarterly format in 1946 did enable Lehmann to commission a set of four seasonal cover designs from Minton, at a cost of £30.

Book covers of 'The Penguin New Writing'

1946, cover designs by John Minton (1917–1957) and edited by John Lehmann (1907–1987)

Believing that there was a market for a new cultural publication, and with the freedom afforded by his having incorporated his own publishing company to launch it, Lehmann conceived Orpheus on a larger scale, a true 'Symposium of the Arts'. His belief in artistic synthesis almost led to the magazine being called 'The Nine' in homage to the Muses of classical mythology, before he decided to use the Greek mythological figure of Orpheus, a poet and musician, to symbolically bring the different arts together in one human form.

Book cover of 'Orpheus: A Symposium of the Arts', Volume One

1948, cover design by Keith Vaughan (1912–1977) and published by John Lehmann (1907–1987)

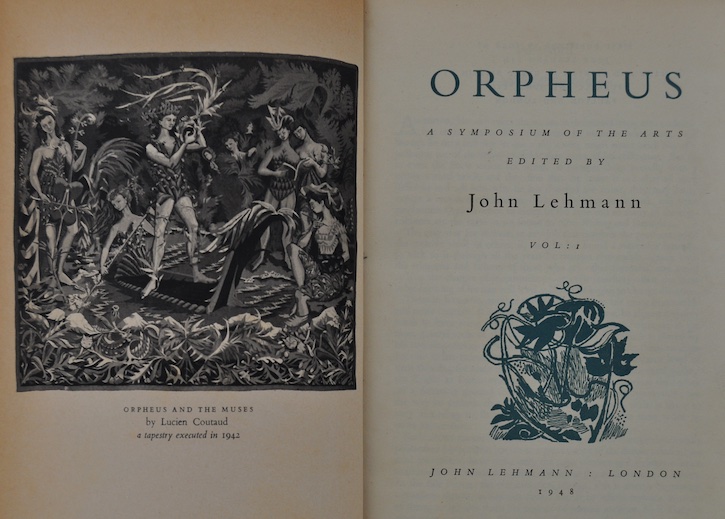

The first edition included a Keith Vaughan rendering of Orpheus walking through a landscape as its dust jacket (alongside his painting Workmen with a Weather Vane, shown above) and reproduced a lavish 1942 tapestry of Orpheus and the Muses by French painter Lucien Coutaud as its frontispiece.

Title page and frontispiece of 'Orpheus: A Symposium of the Arts', Volume One

showing 'Orpheus and the Muses' (1942), a tapestry by Lucien Coutaud (1904–1977), published by John Lehmann (1907–1987) in 1948

Lehmann saw the new journal as an opportunity to do something 'typographically more pleasing... more richly embellished and more adequately illustrated'. This change in format mirrored an editorial desire to seek out 'what is adventurous in thought or imagination... what is visionary rather than what is merely realistic, what rejects the dogmas and what looks at truth everyday with fresh eyes'. This was particularly evident in the journal's advocacy for Neo-Romantic art.

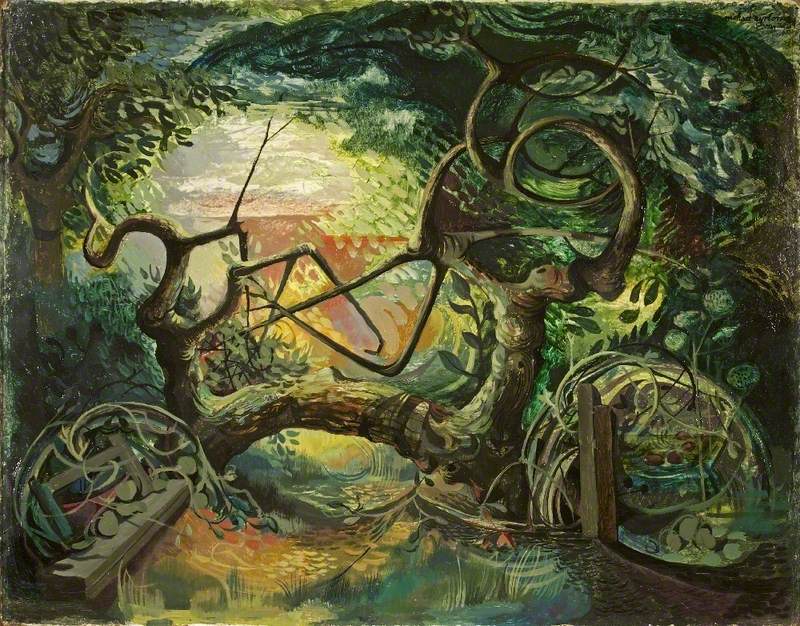

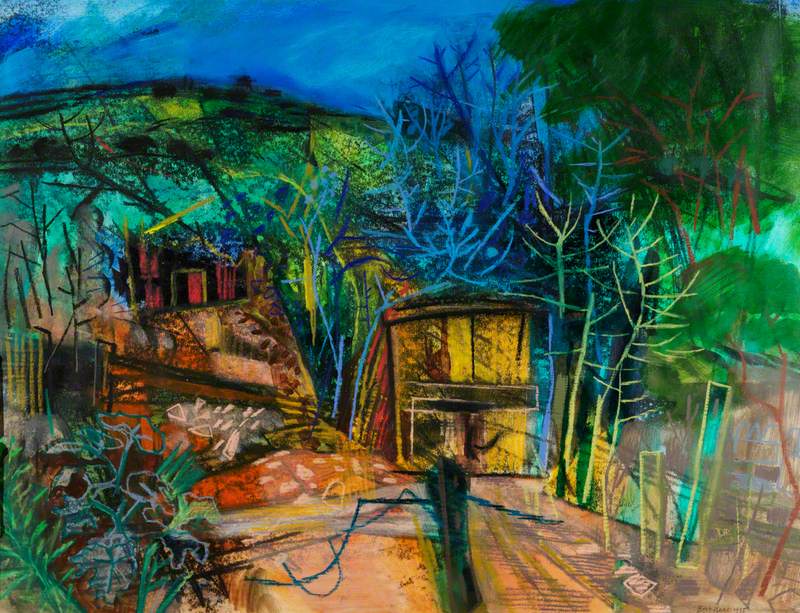

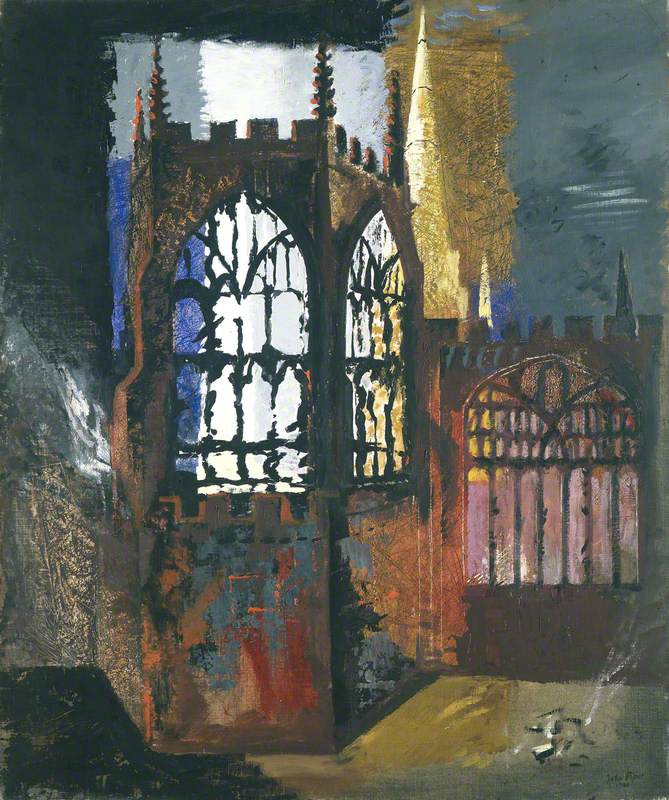

Neo-Romanticism had developed during wartime, with many of its practitioners featuring in the touring 1942 'New Movements in Art' exhibition and the subsequent 'Contemporary British Painting' show at London's Lefevre Gallery. Given the movement's strong sense of place it was ideally suited to a Britain where, having been reminded of its topographical riches when faced with the threat of invasion, painters looked to the landscape for its expressive potential, indebted to the past but containing some of the uncertainties of the future.

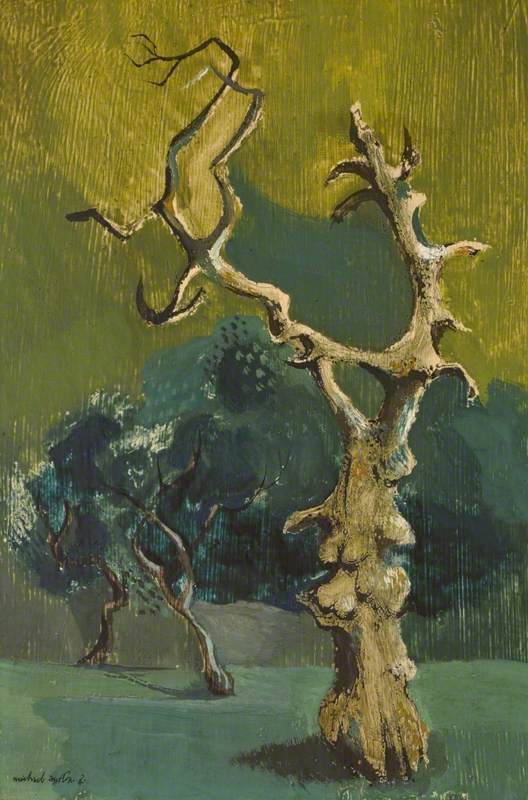

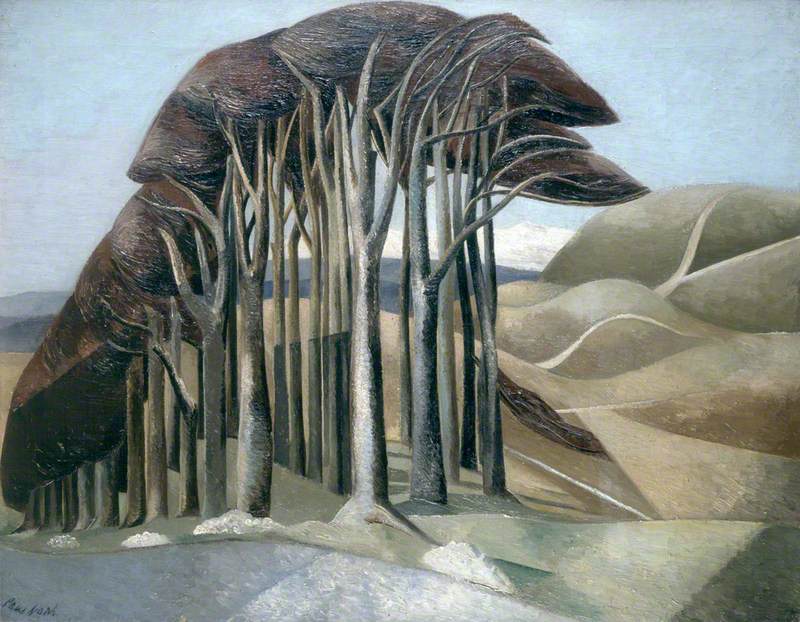

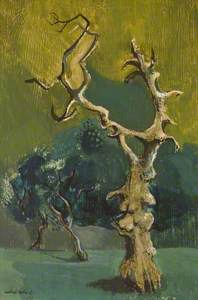

What might have been deemed familiar subjects and motifs were rendered in such a way as to give a sense of place which looked back to the visionary work of William Blake (1757–1827) and Samuel Palmer (1805–1881), rather than conventional Victorian landscapes. Neo-Romantic nature could seem darker and less recognisable, twisted like the trees in Ayrton's paintings.

Lehmann had always been a keen supporter of Neo-Romantic artists, and while including their work in The Penguin New Writing had been a useful way of raising awareness, Orpheus, with its larger, more expansive format could include more reproductions alongside analytical essays and artists' statements.

Ayrton's Entrance to a Wood (1945) appeared accompanied by a short text in which the artist explored his vision and practice, 'the gamut of emotions living trees can inspire; the genial good-will of trees sunbathing, the terror of bare windblown trees, the lonely grief of isolated trees under rain, or the curious conspiracy of trees in woods'. Although still reproduced in black and white, readers could consult the artwork after reading Minton's words and see the product of such an outlook for themselves.

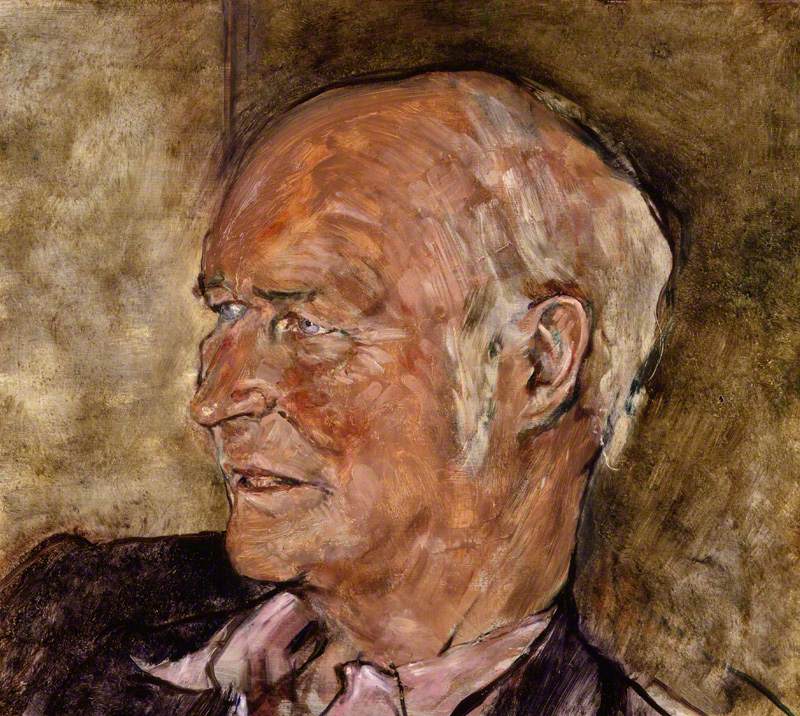

Elsewhere, an essay by artist and writer Michael Middleton on 'Four English Romantics' explored the work of Ayrton, Minton, Vaughan, and Leonard Rosoman. There were no fewer than 46 illustrations in the first Orpheus, spread over 24 pages, with Neo-Romantic art making up more than half of these alongside French tapestry designs and images from ballets at Covent Garden and Royal Shakespeare Company productions at Stratford.

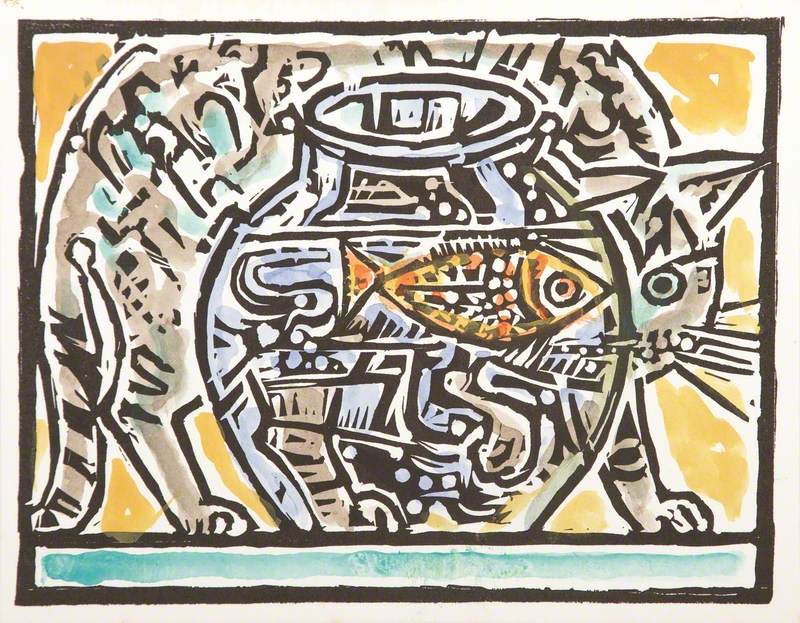

Alongside his dust jacket design for the first issue, Vaughan devised smaller motifs to serve as decorations at the end of poems, stories, and essays. Having also devised a new cover artwork, Minton would fulfil a similar role in the second edition, with Lehmann having given him his own copy of engraver John Pine's 1733 edition of the works of the lyric poet Horace as a starting point for his internal designs. Lehmann was delighted with the resultant set of 'tail-pieces in which classical motifs were married to John's romantic lyrical fantasy'.

Recalling the project nearly 20 years later, Lehmann referred to Orpheus as 'an out-and-out anti-austerity production', adding that the 'thrill of pleasure' he felt on seeing the first issue 'is still renewed today, whenever I take the volume out of the shelf'.

As aesthetically pleasing as it was, however, the economic realities of the journal proved harder to ignore. Faced with rising costs, falling sales, and a wider restructuring of Lehmann's publishing interests, Orpheus ceased in 1949 after just two issues. The 'symposium of the arts' had, in being as broad as possible, failed to translate critical approval into commercial viability.

Many of the writers and artists that it had showcased would go on to find greater renown, not least the Neo-Romantics whose works would come to feature prominently in both public and private collections.

Writing in 1951, the critic Herbert Read noted that 'the genius of our greatest painters no less than of our greatest poets was always romantic. In that sense the general trend of contemporary art may be interpreted as a return to our romantic tradition'. Although itself a brief and extravagant publication, Lehmann's Orpheus helped to place the Neo-Romantics firmly within Britain's post-war artistic landscape.

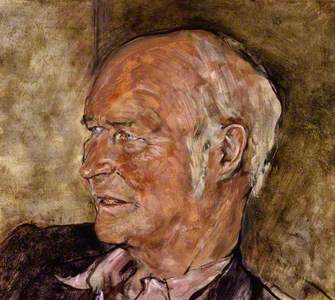

Peter Lowe, writer and academic

This content was supported by Jerwood Foundation

Further reading

John Lehmann, The Ample Proposition: Autobiography 3, Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1966

Herbert Read, Contemporary British Art, Penguin, 1951

Frances Spalding, John Minton: Dance Till the Stars Come Down, Hodder & Stoughton Ltd, 1991

Adrian Wright, John Lehmann: A Pagan Adventure, Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd, 1998

Malcolm Yorke, The Spirit of Place: Nine Neo-Romantic Artists and Their Times, Constable, 1988