Revolution was in the air in the final decades of France's eighteenth century. While the streets of Paris buzzed with political upheaval, a less visible – yet no less profound – revolution was taking place in the art world, as women were claiming their space in a world that had long been dominated by men. Some of these artists – women such as Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842) – achieved such renown that they are now among the most celebrated artists from this period.

Self Portrait in a Straw Hat

after 1782

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842)

Overcoming the abundant hurdles in their paths, they became influential art-world figures who shaped the production and consumption of art in Paris during this turbulent period of change.

Vigée Le Brun and her colleagues were not Europe's first women artists. Many women had successful careers as artists before the eighteenth century – such as the Italian Renaissance painter, Sofonisba Anguissola (c.1535–1625) or the Baroque painter, Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1654 or after). So what was different about the closing decades of France's eighteenth century?

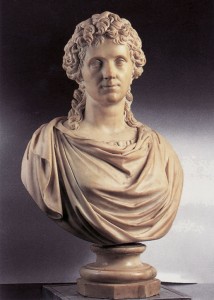

Self-Portrait

c.1770, pastel by Marie-Suzanne Giroust (1734–1772)

What was distinct about this moment was the beginning of a collective movement for change. Women such as Vigée Le Brun, Marie Suzanne Giroust (1734–1772), Marie-Thérèse Reboul (1735–1806), Anne Vallayer Coster (1744–1818), Adélaïde Labille Guiard (1749–1803), Marie-Victoire Lemoine (1754–1820), Marie-Gabrielle Capet (1761–1818), Marguerite Gérard (1761–1837) and Marie-Denise Villers (1774–1821) – to name just a handful – all wanted successful careers as individuals, but together, they also began to generate a growing impetus to change the structures around them. In other words, to make a permanent and enduring space for women in the art world – for themselves and for generations to follow.

Portrait of an Elderly Woman with Her Daughter

1775

Anne Vallayer-Coster (1744–1818)

Dealing with the Academy

Old Regime France (the period before the French Revolution) was not an easy place to be a professional woman artist. Paris's art world was then dominated by the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, an extremely hierarchical institution where the kingdom's most elite artists – the academicians – established the rules of art and trained students to follow that practice. The problem for any aspiring woman artist, however, was that the Academy was essentially a men's-only space. Throughout the institution's entire existence, over a century and a half (1648–1793), only 15 women were admitted as academicians and no female students were permitted to train.

The exclusion of women as students was justified at the time as an issue of decorum. The Academy's main teaching activity was the life class, which involved students drawing a nude male model under the guidance of an academician. This was deemed an inappropriate activity for ladies. But the exclusion of women as academicians was more blatant.

Life Class at the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture

1746

Charles Joseph Natoire (1700–1777)

The Academy didn't just overlook women artists, it actively prevented their inclusion by setting gendered restrictions on membership. Women academicians were banned entirely at the start of the eighteenth century, but that rule was changed in the 1720s so they could admit the famous Italian pastelist, Rosalba Carriera (1673–1757). In 1783, just after the Academy admitted both Vigée Le Brun and Labille Guiard, the academicians voted to change the rule again, to set a limit of only four women members at any time. It was no coincidence that the number of women members at that point was (you guessed it) four.

Meeting of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture at the Louvre

1717/1718, oil on canvas by Jean-Baptiste Martin (1659–1735)

Only a tiny minority of women ever managed to join the Academy – the first was Catherine Duchemin in 1663; the last were Vigée Le Brun and Labille Guiard in 1783. But even these artists did not share the same opportunities as their male colleagues. No woman was ever promoted beyond the entry rank of academician, which meant none ever had voting rights within the institution. In a roundabout way, this was due to the Academy's peculiar restrictions around subject matter, which art historians call the 'hierarchy of genres'.

History painting (e.g. religious or mythological scenes) was considered the highest genre and everything else (landscape, portraiture, still life, genre painting) was considered a 'lesser' genre. When entering the Academy, painters were admitted into one of these genre categories – Vallayer Coster, for instance, was accepted as a still life painter. But only history painters could be promoted to those influential senior ranks and (you guessed it again) no woman was ever admitted as a history painter.

Despite all the restrictions, there were certainly advantages for women artists who became academicians. Aside from the prestige of the appointment, and access to important art world networks, perhaps the greatest benefit was the opportunity to exhibit in the Academy's Salons. These public exhibitions, held biennially at the Louvre, were immensely popular and allowed artists to present their latest works to large audiences, including art critics and prospective customers.

A studio of one's own

With the Academy gatekeeping entry, women needed alternative spaces in the art world. For most women artists in eighteenth-century France, the studio was a far more important space for establishing an artistic career. All artists' studios in this period were part of the home. As private spaces – beyond institutional control and public sanction – the studio was therefore a crucial environment in which women could practice independently, to create art, to network with clients, and even to serve as teachers.

A vision of the studio's role in this sense was captured by Labille Guiard in her celebrated self-portrait with two students, Marie-Gabrielle Capet (1761–1818) and Marie Marguerite Carreaux de Rosemond (1765–1788).

Yet even the studio was a complicated space. In a patriarchal society where women's property rights were limited and where few women lived independently, most women's access to a studio depended on male relatives granting them space, permission, and resources. It is no coincidence that so many women artists were part of artistic families, where a studio was available and support was offered. This is why we find many instances of artist couples – such as Giroust, who married the academician, Alexander Roslin (1718–1793) – shown here working together – and Reboul, who married Joseph-Marie Vien (1716–1809).

It also explains many artistic sisterhoods – like the Horthemels sisters (Louise-Magdeleine, 1686–1767, Marie-Nicole, 1689–1745 and Marie-Anne-Hyacinthe, 1682–1727), all of them engravers; or the trio of painter sisters, Lemoine, Villers and Marie-Élisabeth Gabiou (1761–1811).

In fact, Lemoine's painting of The Interior of a Woman Painter's Studio is believed to be a self-portrait alongside her younger sister Marie-Élisabeth. More significantly, she also shows herself in the act of creating a history painting. Lemoine wasn't an academician, so she wasn't able to exhibit this painting at the Paris Salon until 1796, following post-Revolutionary art-world reforms that increased opportunities for women artists.

The Interior of a Woman Painter's Studio

1789, oil on canvas by Marie Victoire Lemoine (1754–1820)

Family connections weren't always direct. Marguerite Gérard, for instance, gained access to a studio at the age of eight, when her sister married the academician, Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806).

A Young Lady and a Little Girl

c.1785–1790

Marguerite Gérard (1761–1837) (attributed to)

Gérard trained in her brother-in-law's studio from the age of 16 and ended up collaborating with Fragonard throughout their careers, while also developing her own successful independent practice. They were even known to work together on the same paintings, like The Reader, attributed to both Fragonard and Gérard.

Studios were educational spaces, but they were also social spaces. This was especially so for portraitists, who hosted clients for sittings and sometimes created influential social networks as a result. Vigée Le Brun and Labille Guiard were two painters who ended up boasting some of the most glittering figures of eighteenth-century Paris among their clientele. We see this in works such as Labille Guiard's portrait of the Duc de Choiseul, the First Minister of State, and Vigée Le Brun's portrait of the Duchesse de Polignac, best friend of queen Marie-Antoinette.

Etienne-François (1719–1785), duc de Choiseul-Stainville, at His Desk

1786

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749–1803)

Martine-Gabrielle-Yoland de Polastron (1745–1793), duchesse de Polignac

1783

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842)

Aside from the commercial benefits of commissions like these, painting the portraits of such powerful figures also brought great prestige and social capital. During their portrait sittings, artists such as Vigée Le Brun and Labille Guiard had the ears of some of the most powerful people in the kingdom.

Despite the success of women artists in eighteenth-century France and the collective movement they started, momentum was slow to take hold. In fact, over the next generations, things progressed very little. Throughout the nineteenth century, women artists continued to face many of the same struggles when it came to institutional restrictions and access to studios.

A century later in the 1880s, for instance, at the peak of Berthe Morisot's (1841–1895) career, this celebrated Impressionist had no studio of her own. It wasn't until the very end of her life, after her husband's death, that she finally established her own studio. Those revolutionary decades of the eighteenth century started the promise of change, but it was just the beginning of a much longer struggle.

Dr Hannah Williams, Reader in the History of Art at Queen Mary University of London

This content was supported by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation