One day in the 1990s a man was out for a sorrowful walk around the rubble of his former workplace. He saw a face he recognised, smiling faintly, looking up from a skip.

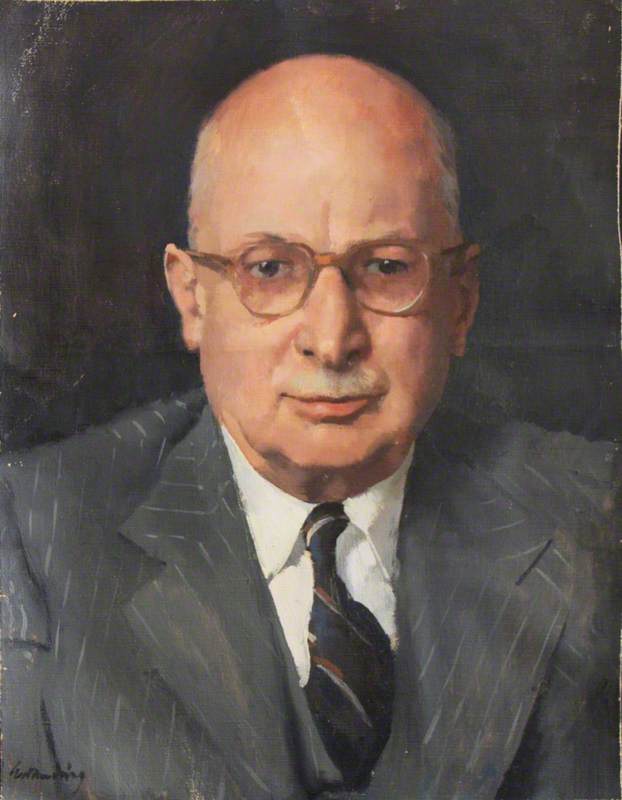

When the portrait of Oscar Viney went on display at the Royal Academy in 1958, immaculate in his grey pinstripe suit – apart from, endearingly, a tie very slightly askew – he was the very model of a sleek and prosperous home counties businessman. It would take the combined talents of the Buckinghamshire County Museum and Art UK's Art Detective to puzzle out the origins and fate of his portrait, and the downfall of his workplace.

Colonel Oscar Vaughan Viney (1886–1976), TD of Hazell, Watson and Viney Ltd

exhibited 1958

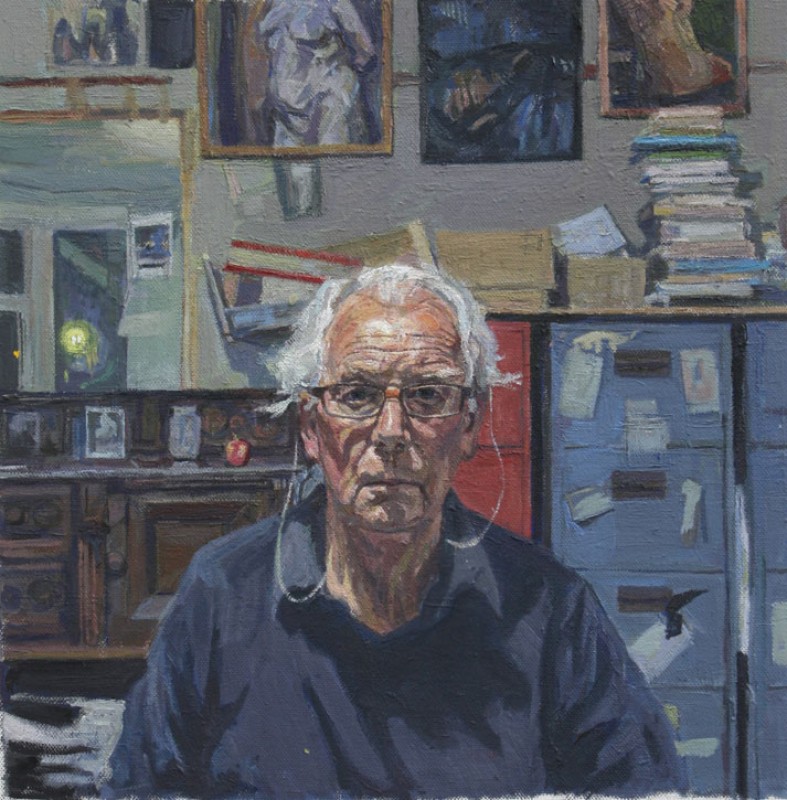

William D. Dring (1904–1990)

Viney was a decorated war hero, a former Commander of the Bucks Light Infantry, High Sheriff of Buckinghamshire, and chairman of one of the county's leading industries, Hazell, Watson and Viney printers. Within a generation, the handsome works buildings on the outskirts of Aylesbury would be rubble, and his own portrait, with those of his senior partners which had hung together on the boardroom walls, would be cut from its frame and dumped into a skip in the wasteland.

The man who found them, and wishes to remain anonymous, was a former printer who had been an employee of Viney’s. He couldn't bear to leave the portraits to rot, so he rescued all four, and later donated them to the Bucks County Museum. He also salvaged the frames, but by then they were battered beyond being accessioned.

Although the paintings were tattered, Melanie Czapski, curator of art and studio ceramics, says the museum was delighted to accept such a key piece of local history.

The firm's earliest known printing order, soon after it was founded in London in 1839, was for modest trade cards for a Victorian laundryman in London, one M. L. Turner, a 'clear starcher and ironer and

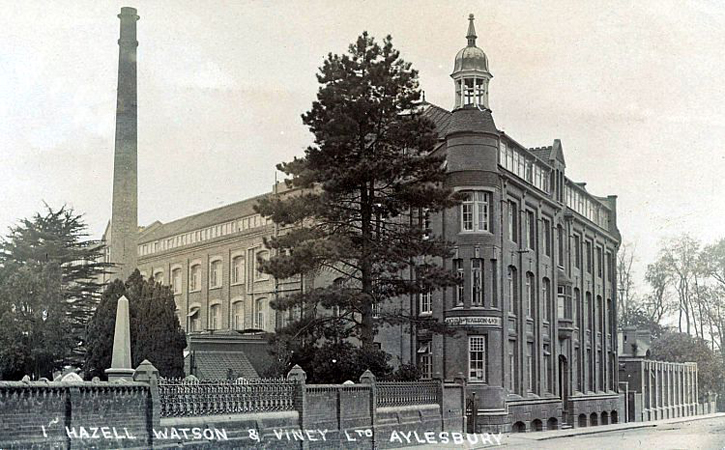

Hazell, Watson and Viney building in Aylesbury

The Aylesbury connection began when it was bought by a Bucks printer. The firm was particularly known for illustrated magazines and books, and the official company history took special pride in the sets of Dickens novels which still turn up in second-hand bookshops all over the country – in one 16-week period in the early twentieth century they printed 300,000 16-volume sets.

At its height in

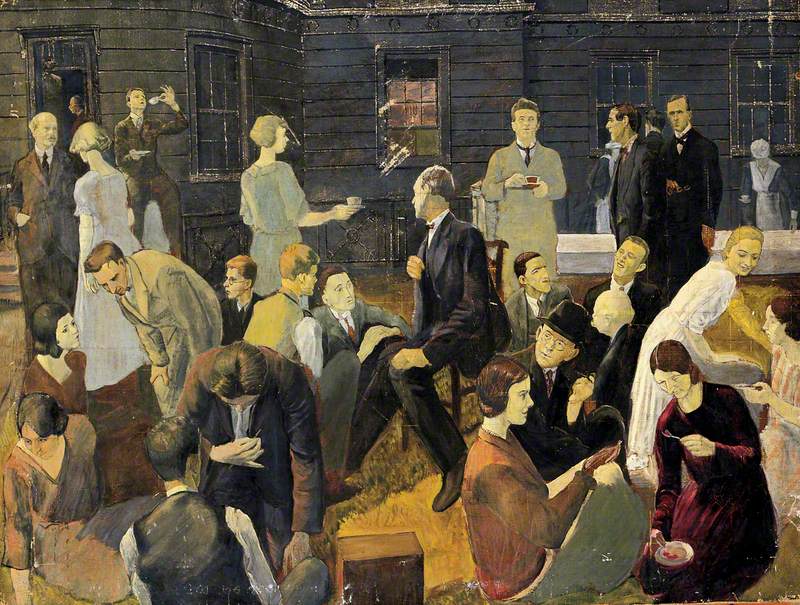

When the paintings came to the museum the staff knew nothing of them, except for a 1920s photograph in the history which showed the boardroom with portraits on the walls. The quality was extremely variable, the condition dire, and the magnificently bearded George Watson Junior seemed to have been copied from an engraving in the book.

Oscar Viney

However, they recognised Viney, unquestionably the best picture and in the best condition, from photographs in their own collection, which had been donated by his family along with his sword and gorgeous dress uniform. The portrait and uniform, normally kept in store, were on display in the main museum for a 1914 centenary exhibition, which recorded the rather unglamorous injury which brought Viney back from the front after he slipped and fell into a trench.

Will Phillips, keeper of social history, with Colonel Viney's dress uniform

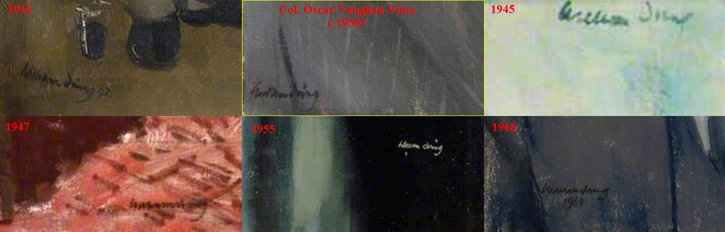

The curators could make nothing of the signature, and it took the Art Detectives to puzzle it out when it went up on the site. Grant Waters beat Osmund Bullock to the identification by eight minutes: Waters recognised the artist immediately, Bullock the mouth.

Comparison of Dring's signatures

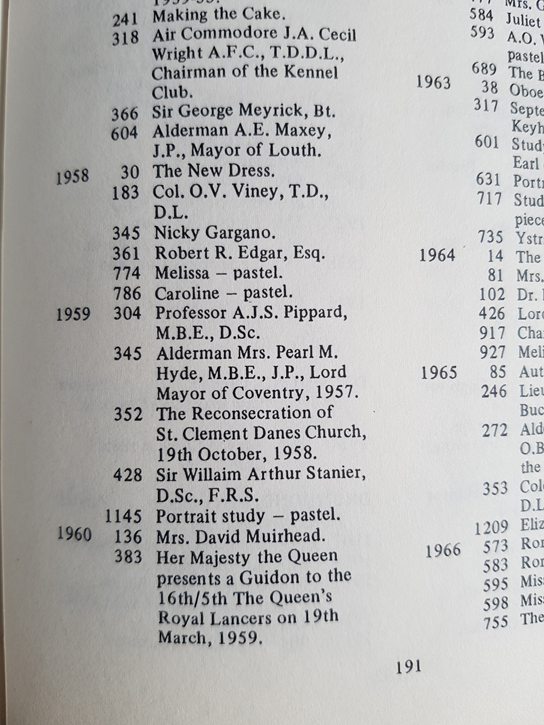

The portrait, it is now clear, was the work of William D. Dring (1904–1990), RA, very well known in his day, now almost forgotten, partly because so many of his works were commissions for private collections. The Imperial War Museum has many examples of his work, and an archive of correspondence about his dealings with the War Artists Advisory Committee of the Ministry of Information, for which he worked extensively in the Second World War. He left a teaching job at Southampton School of Art to take up a salaried post with the WAAC, mainly as an Admiralty portrait artist, under constant threat of being called up if his contract was not renewed. His work continued as a prolific portrait painter after the war, and Waters believes the picture must be the Col. O. V. Viney TD DL which Dring exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1958.

The catalogue entry for the Royal Academy showing Dring's portrait of Viney

It was not the signature but the distinctive mouth, with the slight sweet smile, which Bullock recognised: Viney died in 1976, but Bullock had known his son Lawrence, a good friend of his own father. He still remembers the gentle kindness of Lawrence, then frail and walking with the aid of two sticks, when he insisted on coming to his father’s funeral.

Melanie Czapski says the museum is delighted with the wealth of extra information gleaned by the Art Detectives. The Viney collection may one day go on display again, as Will Phillips, keeper of social history, is considering an exhibition on the printers. In the meantime, the stores can be visited by appointment, for which there may be a small charge, but with enough

Maev Kennedy, writer