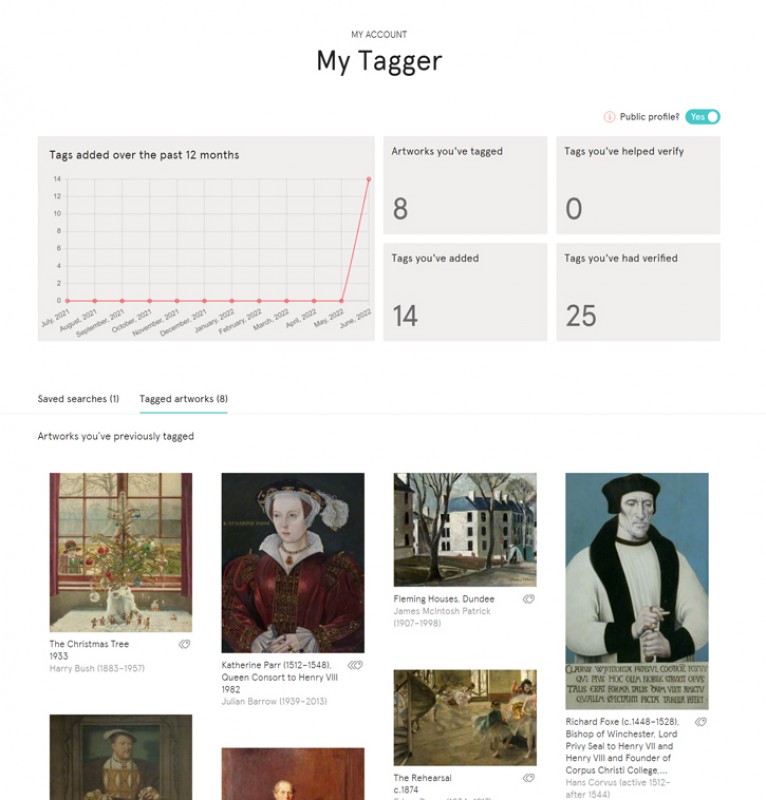

On 11th November, hundreds of thousands of people all over the UK take part in ceremonies to remember those who have fallen during the two World Wars and in subsequent conflicts. 2018 held special significance, however, as it marked the 100-year anniversary of the end of the First World War.

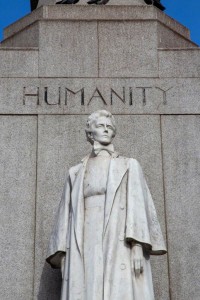

In the years immediately following 1918, countless war memorials were erected all over the country. Indeed almost all of the nations who were represented in the conflict erected collective memorials to their dead. These ranged from simple village crosses and plaques to monumental edifices involving the most renowned sculptors and architects of the time.

The impracticality of returning war dead to their families and hometowns caused widespread anger and resentment and one of the functions, particularly of the governmental memorials, was to provide a place where families and communities could mourn, through rituals of collective memory, and grieve for those that they had lost. They also served as places to remember those whose bodies were never found, or never identified; in Kipling's words, 'A soldier of the Great War known unto God' – the inscription used on Commonwealth War Graves Commission headstones.

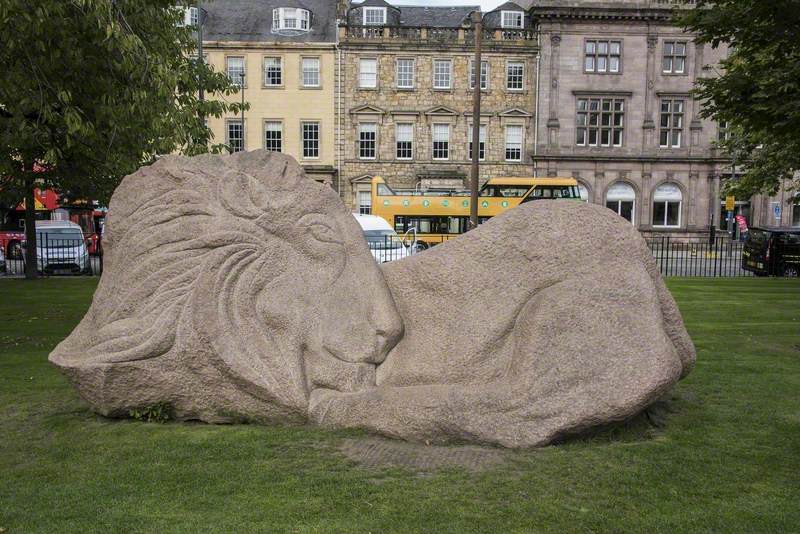

Image credit: Tracy Jenkins / Art UK

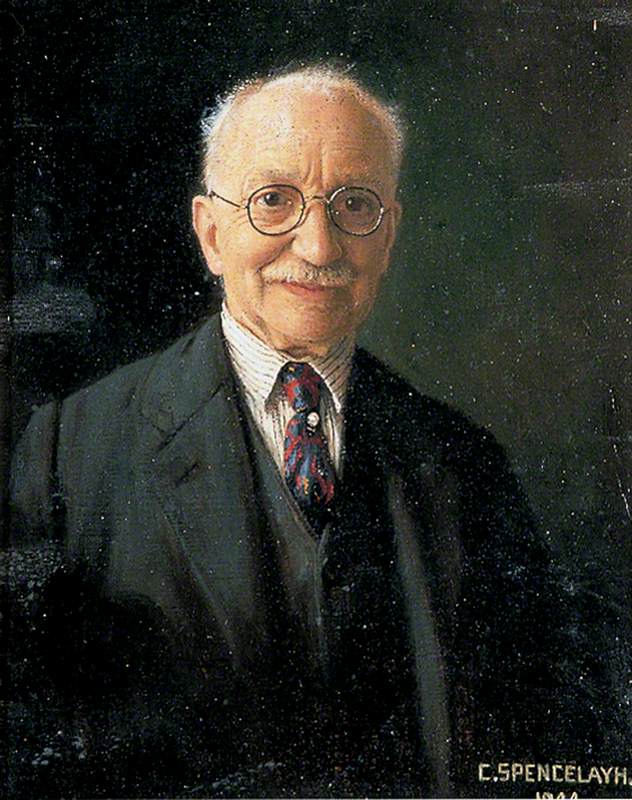

Edwin Landseer Lutyens (1869–1944) and Holland, Hannen & Cubitts and Francis Derwent Wood (1871–1926)

Whitehall, WestminsterWar memorials took many forms and the iconography varied. The Cenotaph in Whitehall, London, by Sir Edwin Lutyens (1869–1944) and unveiled on 11th November 1920, became the UK's official national war memorial. Constructed as a simple, and elegant pylon with very few design features, the word 'cenotaph' comes from the Greek, literally meaning 'empty tomb'. Many other memorials featured a range of allegorical statues, a 'Winged Victory', for example, or statues of Saint George vanquishing the dragon, symbolising the victory of good over evil.

Image credit: Iridescenti, CC-BY-SA-3.0, from Wikimedia Commons

Royal Artillery Memorial at Hyde Park Corner, London

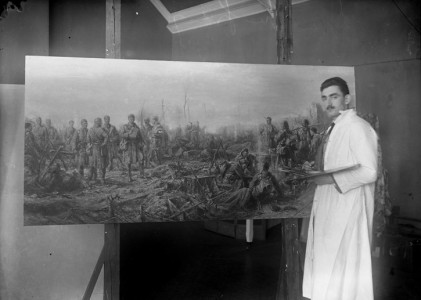

The Royal Artillery Memorial at Hyde Park Corner, London, a Grade I listed monument, took a realist approach in its design, creating both controversy and, indeed, continued debate. It was designed by the sculptor Charles Sargeant Jagger (1885–1934) and architect Lionel Pearson (1879–1953) and includes a giant sculpture of a BL 9.2-inch Mk I howitzer upon a large plinth of Portland stone, with reliefs depicting battle scenes.

Image credit: Tracy Jenkins / Art UK

Royal Artillery Memorial 1921–1925

Charles Sargeant Jagger (1885–1934) and Lionel Pearson (1879–1953)

Hyde Park Corner, WestminsterFour bronze figures of artillerymen are positioned around the outside. The inclusion of a life-size prone statue of a fallen soldier is particularly dramatic and was in complete contrast to other memorials created around the same time. It was unveiled on 18th October 1925. Jagger was himself a veteran of the conflict and a recipient of the Military Cross. Soon after creating the memorial he was awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal Society of British Sculptors and made an Associate of the Royal Academy.

There are other significant First World War memorials that feature realistic and dramatic depictions of the battlefield. Oldham War Memorial on Church Street, Oldham, a Grade II* listed monument, is surmounted by a highly detailed, group statue in bronze, of five infantrymen going 'over the top'.

Designed by Staffordshire sculptor Albert Toft (1862–1949), and Oldham architect Thomas Taylor, of Taylor and Simister, it was unveiled on 28th April 1923.

© the copyright holder. Image credit: Gallery Oldham

Unveiling of the War Memorial, Oldham, Lancashire, 28 April 1923

James Purdy (1900–1972)

Gallery OldhamThe Lancashire cotton town suffered enormous casualties during the war, with official estimates suggesting 2,688 people lost their lives.

The memorial has several notable features. The base contained a 'sacred chamber' with two sets of bronze doors, which was a space containing the Rolls of Honour for the local 'pals' battalions, and where visitors could quietly pray.

Image credit: Pamela Jackson / Art UK

War Memorial

Albert Toft (1862–1949), Yorkshire Street, Oldham, Greater Manchester

In the mid-1950s the doors on the south side were replaced with a glass covered mechanical Roll of Honour. The dedicatory names are unusual in that they include that of Mabel Drinkwater, a First World War nurse who died on the operating table during routine nasal surgery at Oldham Royal Infirmary.

Toft used the model for the topmost figure in several other war memorials that he designed, including the Royal Fusiliers' Memorial in Holborn, London.

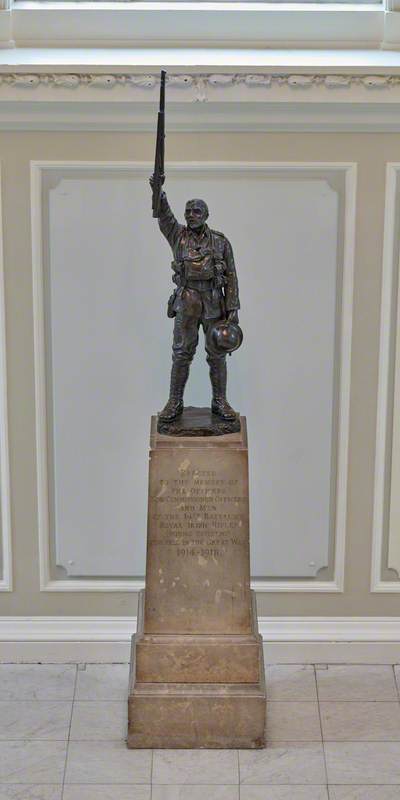

Many towns and cities erected memorials to specific local regiments, faithfully recreating every detail of their uniform in bronze or stone. The 3rd Battalion of the Monmouthshire Regiment was based in Abergavenny and a particularly beautiful memorial to that battalion was unveiled there on 29th October 1921. Situated on Frogmore Street, the Grade II listed memorial was designed by the sculptor Gilbert Ledward (1888–1960).

© the copyright holder. Image credit: Paul Kirby / Art UK

Monmouthshire Regiment Memorial 1921

Gilbert Ledward (1888–1960) and A. B. Burton (active 1874–1939)

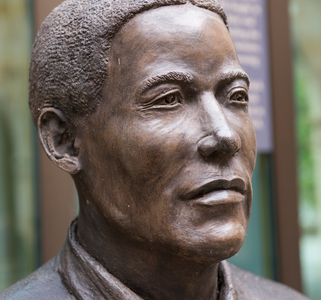

Frogmore Street, Abergavenny, Monmouthshire (Sir Fynwy)Again, approaching his subject with emotive realism, Ledward chose to depict a soldier exhausted after a recent battle. The soldier, in full kit, is leaning on his upturned rifle.

Image credit: Paul Kirby / Art UK

Memorial to 3rd Battalion of the Monmouthshire Regiment, Frogmore Street, Abergavenny

Ledward had served in the Royal Garrison Artillery during the conflict and was subsequently a war artist. Throughout the 1920s he was professor of sculpture at the Royal College of Art and was later elected a Royal Academician.

Image credit: Paul Kirby / Art UK

Memorial to 3rd Battalion of the Monmouthshire Regiment, Frogmore Street, Abergavenny

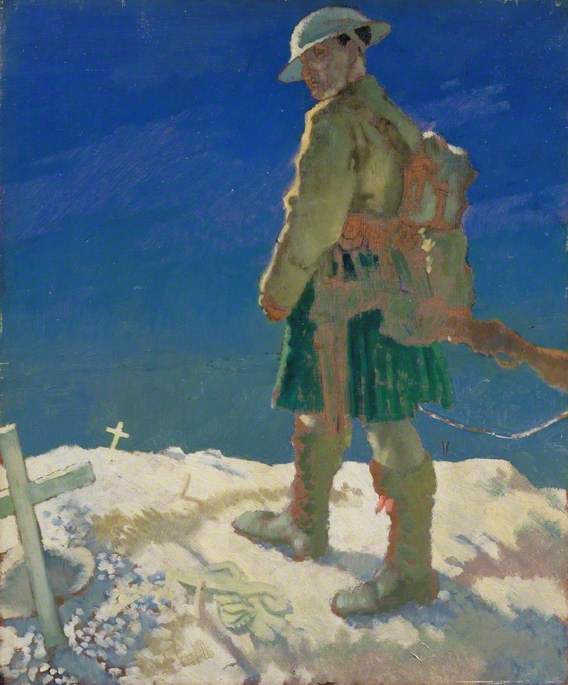

Another fine example, dedicated to local Scottish regiments, can be seen in Inveraray, Argyll and Bute. The Glasgow sculptor William Kellock Brown (1856–1934) created a beautiful bronze of a kilted Highland infantryman wearing a tam o' shanter, for the memorial set on the banks of Loch Fyne. The work was unveiled on 20th August 1922.

A granite plinth carries the poignant dedication:

'In memory of those young loved lamented here who died in their country's service... these are they which came out of great tribulation.'

Image credit: Peter Amsden / Art UK

Inveraray War Memorial, Loch Fyne, Inveraray

Interestingly, during the 1920s the 10th Duke of Argyll built a church tower nearby, as a memorial, to commemorate local losses in the First World War, especially members of the Clan Campbell. The Duke's Tower is some 39 metres high, and, with ten bells weighing nearly 8 tonnes, is said to have the second heaviest peal in the world.

Although the larger, monumental memorials can be incredibly powerful and moving, perhaps the most poignant are those that speak to a more personal and identifiable loss. One such work is the family memorial to the Kennedy brothers in Holy Trinity Church, Cuckfield. Erected by grieving parents after losing three of their sons, it comprises beautiful portrait statuettes of the young men.

All three were captains and each is depicted in his regiment's uniform with a battle scene in relief in the background and individual inscriptions underneath. The memorial was created by the Italian sculptor Filippo Lovatelli.

Archibald, the eldest, a captain in the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, was killed in the first month of the war, while Paul died in 1915 at Aubers Ridge, where his mother subsequently erected a large calvary where he had been last seen. Underneath his portrait statuette, she had inscribed a biblical quote from 2 Samuel: 'My son, my son, would that I had died for thee, my son, my son'; a sentiment undoubtedly shared by thousands of parents who suffered similar losses. The third and youngest brother, John, was killed in the last year of the war, and again, the Latin inscription resonates with the sense of collective grief that many families and communities shared, which translates as: 'The purpose of life with others was the reason why they enjoy companionship now.'

The commemorations relating to the Great War over the past four years have resulted in many new sculptures and memorials. On 11th March 2017, a new statue by Ray Lonsdale was unveiled on Main Street, Witton Park, Bishop Auckland. Again, this work commemorates the loss of specific individuals from the local community.

Titled The Ball and the Bradford Boy it depicts a returning soldier being handed a football by a friend – the ball symbolising the endeavour to return to a previous life before the conflict, what the artist calls 'a reset for his soul'. Lonsdale was also the sculptor of Tommy on the seafront at Seaham.

Image credit: Elaine Vizor / Art UK

The Ball and the Bradford Boy

Witton Park, Bishop Auckland, County Durham

This new statue forms part of a commemorative scheme to recognise the sacrifice of four brothers from the local Bradford family, who between them, were awarded two Victoria Crosses, two Military Crosses and a Distinguished Service Order. Only one of the brothers returned from the war.

Roland Bradford (awarded the Victoria Cross) died at Cambrai in 1917. James (awarded the Military Cross) died of his wounds on the Somme, in 1917. George (also awarded the Victoria Cross) was killed on his 31st birthday in 1918 at Zeebrugge. Thomas (awarded the Distinguished Service Order), the eldest brother, survived the war and was knighted in 1939. George and Roland Bradford were the only brothers in the entire conflict to both be awarded the Victoria Cross.

Image credit: Elaine Vizor / Art UK

The Ball and the Bradford Boy

Witton Park, Bishop Auckland, County Durham

The catastrophic loss of life during the First World War generated a new-found realism about war in the literary and visual arts. The construction of war memorials not only served to help a nation remember and mourn its dead but provided an astonishing sculptural heritage that saw some of our greatest sculptors, architects and craftsmen engaged in their production. These artefacts of cultural memory can teach us much about conflict, loss, and grief but also evidence the incredible skill of those craftsmen and their ability to capture the act of remembrance in stone and bronze.

Anthony McIntosh, Public Sculpture Manager, Art UK