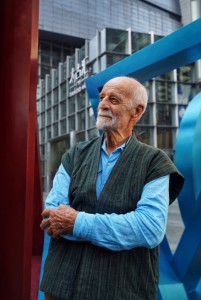

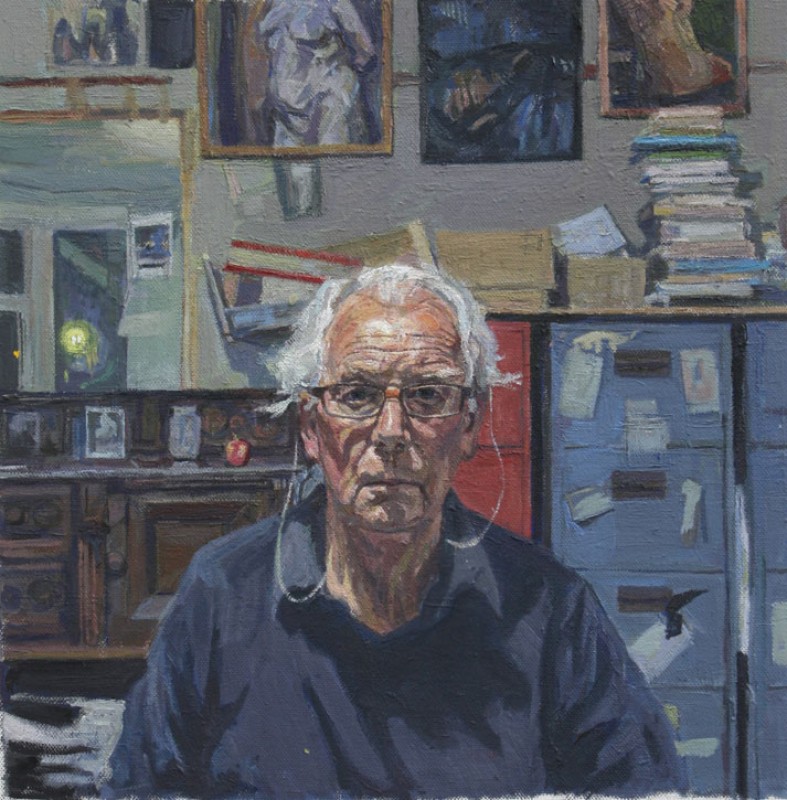

There is undoubtedly a romantic element attached to the rediscovery of a 'lost' artist, righting the injustice of a creative talent that never received enough recognition. What to make, though, of a twentieth-century painter who curtailed his career not long after establishing a name for himself, and despite finding the support of important institutions, galleries, and collectors? This was the case with the London-based painter Keith Cunningham (1929–2014), who during the 1950s was seen as an equal to the likes of Frank Auerbach, once a fellow art-school student.

Despite not having any work shown in public between the late 1960s until only eight years ago, Cunningham has now been awarded the honour of a major show at Newport Street Gallery, 'Keith Cunningham: The Cloud of Witness' (until 21st August 2022), an exhibition that seeks to reaffirm the status of a figure whose oeuvre has been ignored for almost half a century.

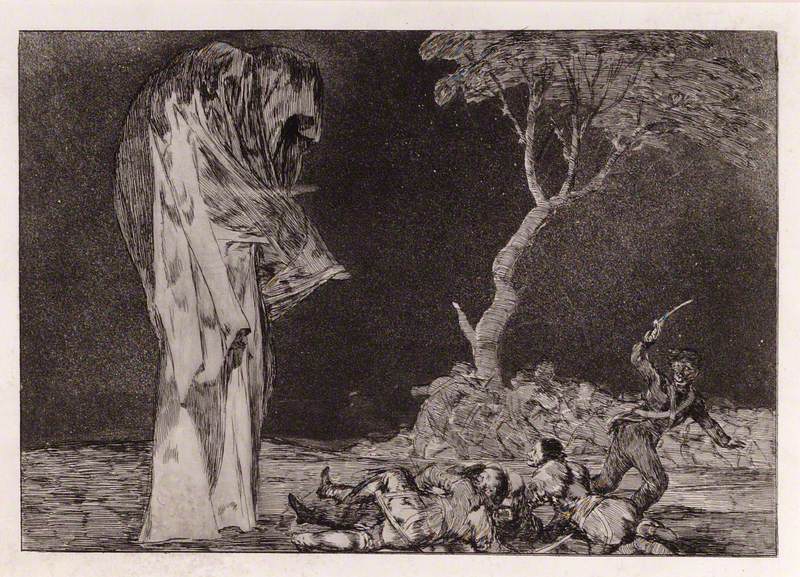

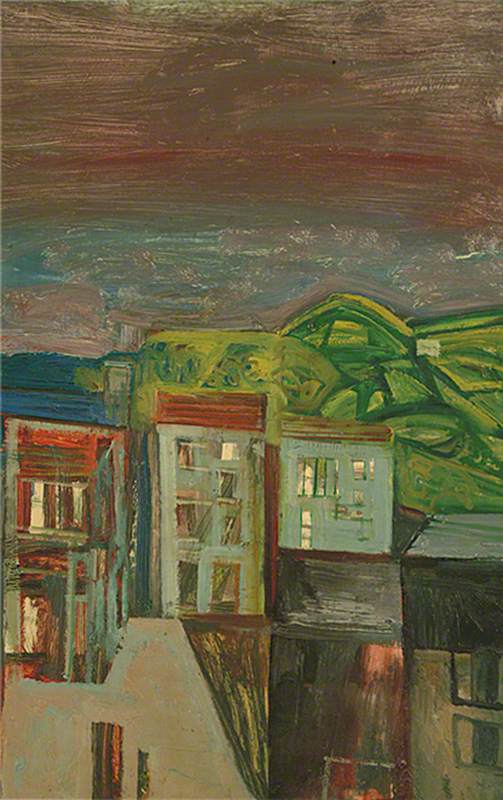

Dogs

1956, oil on canvas by Keith Cunningham (1929–2014)

While it is easy to mythologise lone artists, an air of mystique still surrounds Cunningham, who refused to explain why he abandoned a promising career. His work is also suffused with a dark romance, allusions to death and despair seemingly baked in a hot, rather un-English sun.

In common with his classmates and teachers, the Newport Street Gallery exhibition explains that Cunningham sought to push the limits of figurative painting, 'transforming the reality of everyday life into loose, slowly disintegrating forms'. However, this Australian native's background was very different to the homegrown talents and European refugees he studied with. Born in Sydney, from the age of 15 Cunningham left school and worked in the creative team of a department store, while harbouring ambitions to become a painter.

Aged 20, Cunningham moved to England, where he secured a place to study graphics at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, London between 1949 and 1952. His mentor at the time was another Australian emigré, the designer Gordon Andrews, with whom he worked on murals for the 1951 Festival of Britain (they are now sadly lost). He also met Bobby Hillson, the then fashion student who became his wife and has been instrumental in reviving interest in his work.

In 1952, he joined the fine arts course at the Royal College of Art, where he became a contemporary of Joe Tilson, Auerbach and Leon Kossoff. Cunningham soon emerged as a talent to watch, with painter and tutor John Minton remembering him as an especially promising student, calling the young Australian 'one of the most gifted painters to have worked at the Royal College'.

Auerbach was also impressed by his classmate, describing his early efforts as 'very distinguished... full of nervous life'. In a letter to the Hoxton Gallery, London, which hosted a recent exhibition of Cunningham's work, his friend also pointed out an air of mystery around him, highlighted by one particular idiosyncratic habit: he would leave life drawing classes early to finish compositions elsewhere, painting from memory. Hillson recalled, 'Frank said he was always a bit mysterious. He didn't talk about his work, he talked about other things.'

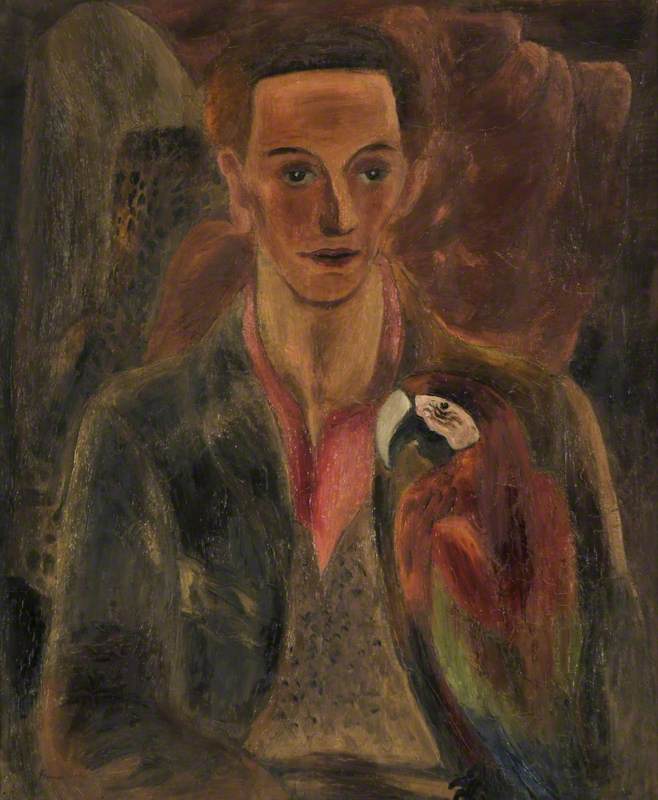

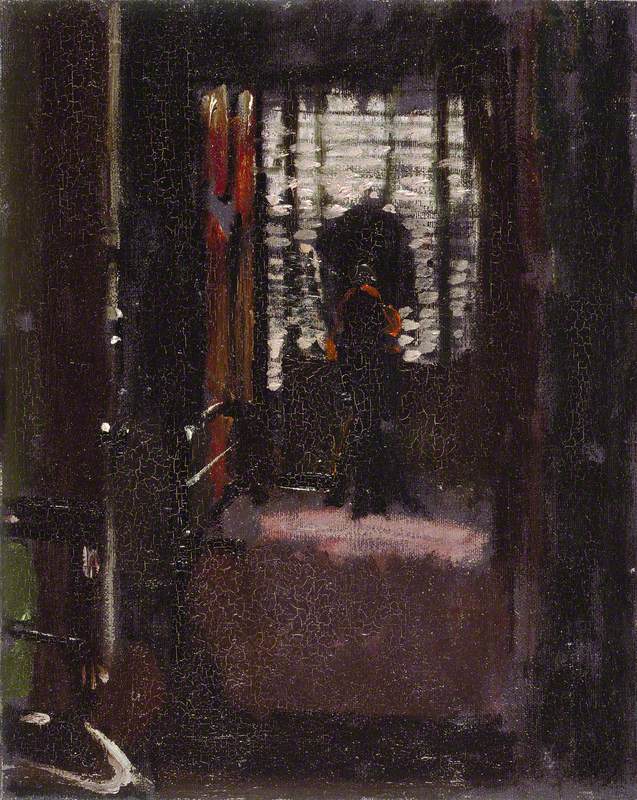

Red Portrait of Frank Bowling

1956–1957, oil on canvas by Keith Cunningham (1929–2014)

Certainly, in terms of his figurative work, Cunningham was less interested in capturing individual personalities than conjuring distinct emotions. The artist rarely attributed full names to any of his sitters, a rare example being his portrait of fellow artist Frank Bowling, which is more silhouette than careful representation.

Access to the Old Masters in European collections was also key to Cunningham's development and following graduation he was awarded a grant to travel to Spain and continue to paint, something that had a huge effect on his style. Similarly to peers such as Auerbach and Kossoff, Cunningham worked with texture: many of his forms appeared as partly abstract, their outlines hidden under thick layers of paint. Yet his works came with a more exotic sheen thanks to a parched palette seemingly inspired by time in the Iberian heat, Hillson believes.

Dogs in Sunlight, Spain

1955, oil on canvas by Keith Cunningham (1929–2014)

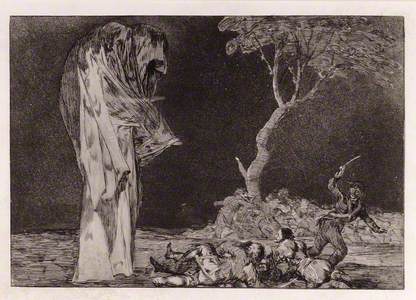

Although she was unable to travel to Spain herself, the then Vogue magazine fashion illustrator was convinced Cunningham had fallen under the spell of the Spanish masters, notably Francisco de Goya, who was also preoccupied with death and decay. 'I don't think there was ever a conscious influence from anyone,' she told Apollo magazine in 2016. 'But unconscious influence, certainly. When you see the whole lot of paintings, there was something very Spanish about it.'

Alongside his indistinct portraits, Cunningham regularly portrayed animals and birds, more often dead than alive: sheep heads, chickens or fish laid out on a table. Sinister dogs appear alone or in packs, often playing or more likely fighting over something. As ever, these forms were created with powerful strokes applying dark pigments.

On his return to London, Cunningham made an instant impact on the art world. His work was accepted for the Royal Academy's Summer Exhibition and appeared in a group show at the influential Beaux Arts Gallery. He became sought after by high-profile collectors, including Hans and Elsbeth Juda, who ensured he became known internationally.

Two Hanging Chickens

1956, oil on canvas by Keith Cunningham (1929–2014)

Cunningham twice exhibited paintings with the prestigious London Group, yet in 1960 when invited to become a member of the artists collective he declined. Seven years later, he abruptly gave up life as a professional artist, refusing all further invitations to exhibit. Instead, he embarked on a successful career as a graphic designer, while also teaching the subject at London College of Printing.

Hillson has been unable to explain why her husband stepped back from the art world, saying, 'Nobody knows why. He never, ever said. But he carefully kept these paintings all his life.' Certainly, it would have been a precarious living early on. Cunningham lacked his own studio space, having almost completed the conversion of a former chapel near the couple's Battersea home that he had been forced to give up. Without ready money to buy canvases or paints, design would have been a safer option.

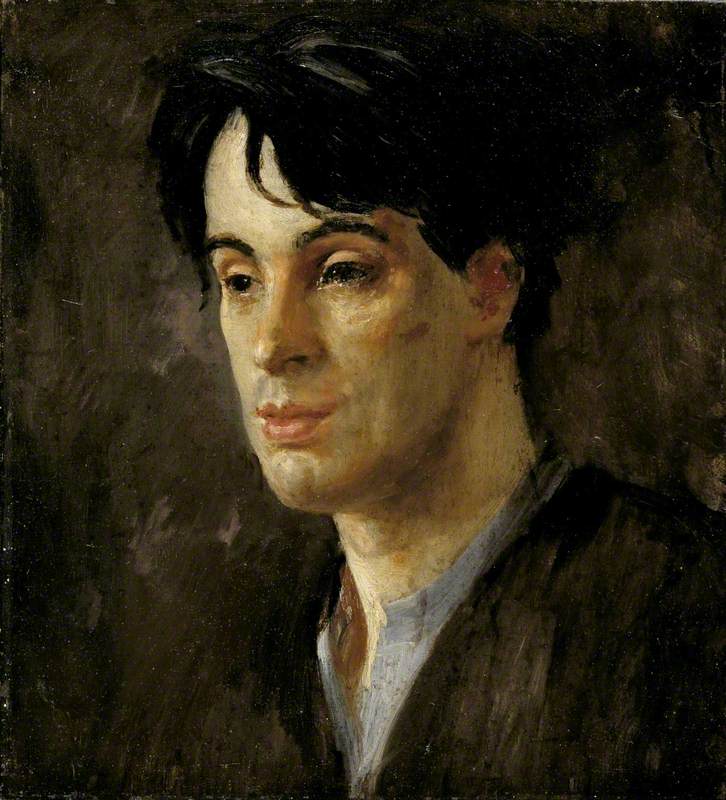

Woman Looking Down

1956, oil on canvas by Keith Cunningham (1929–2014)

Cunningham continued to paint, though, apparently visiting his studio on a daily basis. Following his death in 2014, he left 150 works in oil along with drawings and watercolours. Two years later, his widow helped curate an exhibition, 'Unseen Paintings 1954–60', at the Hoxton Gallery that started the process of rebuilding his profile. The show focused partly on the attention Cunningham gave to heads and skulls.

For the former, the artist preferred to sketch people he saw round London either while travelling on buses or sitting in cafes. The gallery noted the influence of Rembrandt van Rijn in their intensity and sombre palette. An introduction to the show states: 'They are all deeply psychological, evoking a raw humanity that in some works is harrowing.'

Dark Sheep Skull

1957, oil on canvas by Keith Cunningham (1929–2014)

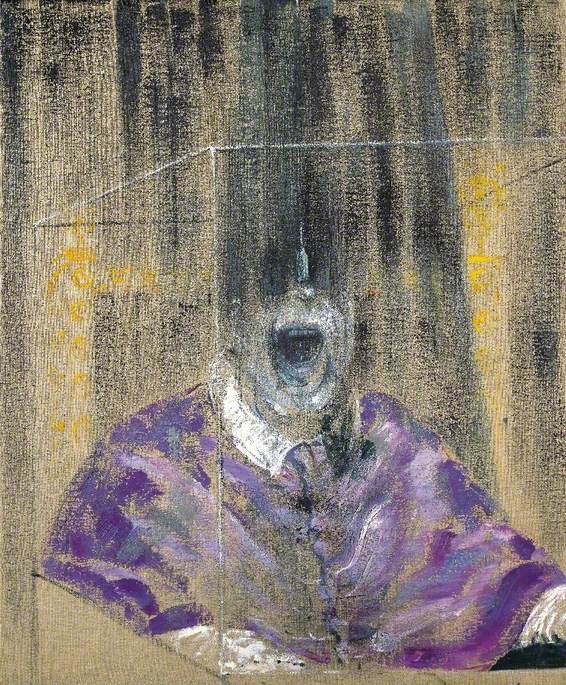

Now the role of celebrating Cunningham's career has passed to Newport Street, currently presenting an exhibition of 70 works that seeks to assert his role in the London art scene of the bohemian fifties. Pointedly, this display coincides with a Royal Academy show dedicated to a more celebrated post-war artist with a fascination for animal forms: Francis Bacon. Whether Cunningham deserves to be spoken of in the same breath as Lucian Freud and Bacon may be a moot point, but the distinctive character of his oeuvre – and the mystique around him – means his work deserves its own place in the sun.

Chris Mugan, freelance writer

'Keith Cunningham: The Cloud of Witness' runs at Newport Street Gallery until 21st August 2022