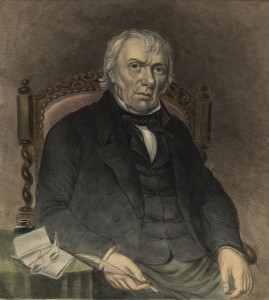

John Parry (1710–1782) was a musical celebrity of his day. A popular performer, composer, and musical publisher, his talent on the triple harp helped establish it as a national icon for Wales, and his legacy lives on in the work of contemporary harpists today. But his achievements are often framed in relation to his blindness, which earned him the nickname Parri Ddall (Blind Parry).

Was he the only blind harper from Wales? No. But he was the most famous, and his huge success paved the way for others, like Will Penmorfa, to rise through the ranks.

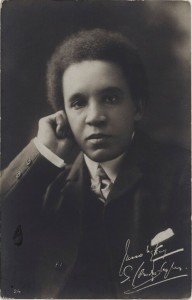

The Blind Harpist, John Parry (1710?–1782)

c.1770

William Parry (1742–1791)

Many stories about John Parry's life speak of how he 'overcame' blindness to achieve extraordinary success. This narrative ventures dangerously close to stereotypes of the 'supercrip', which goes something like: 'this person has overcome the hardship of their disability to achieve exceptional things – what an inspiration!' It is most often seen in athletics, but also creeps into cultural fields like music and the arts.

At first, this might not seem problematic – he was hugely successful, and that's worth celebrating, right? But the supercrip trope sees the disability first, rather than the person. It sets an unrealistic expectation for other disabled people, suggesting their lives are only worth celebrating if they achieve exceptional things. And it values the disabled person in terms of their ability to inspire non-disabled people.

This is reflected in accounts of John Parry's life. Despite his many achievements as a performer and composer, he was just as famous as the inspiration behind The Bard, an epic poem written in 1757 by English poet, Thomas Gray.

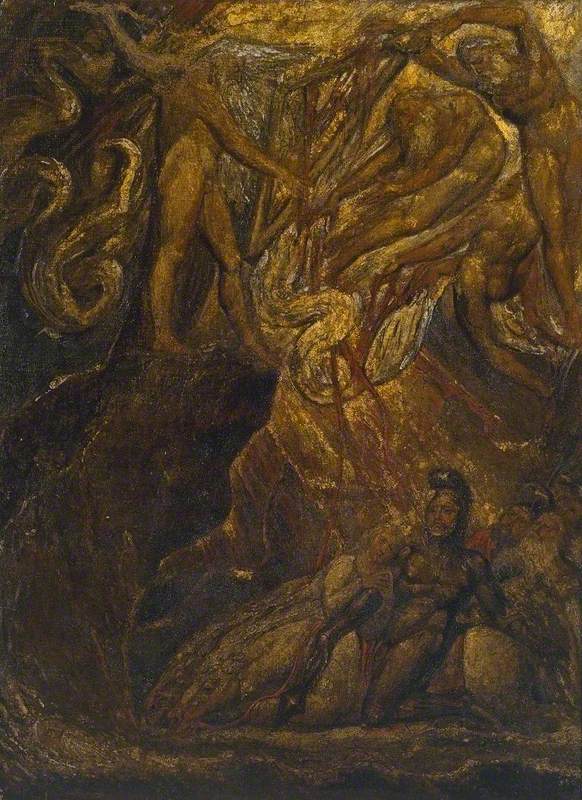

Gray was moved almost to tears listening to Parry's 'ravishing blind Harmony', and this compelled him to write a long and melodramatic ode exploring grand themes of national identity, heroism, prophecy, language and loss. The Bard was seen as a masterwork of the Celtic Revival. It inspired many other poets, artists and musicians to delve into the bardic history of ancient Britain and explore the figure of the bard in their work.

These are often Romantic visions of hoary old men with flowing white beards – think Dumbledore – usually posed in dramatic circumstances. In Thomas Jones' iconic painting The Bard at National Museum Cardiff, the last bard of Wales is poised at the edge of a cliff in Snowdonia, being persecuted by Edward I and his troops. The bard casts a final curse on the English throne before throwing himself into the churning water below.

Note how Gray wasn't struck just by Parry's talent – it was specifically his 'blind Harmony' that inspired him to write The Bard.

There's a long-standing association between bards and blindness. The 'blind seer' has become a common trope, as though the lack of physical sight is necessary to develop a divine inner vision. Homer, Tiresias and Ossian have all been imagined as blind prophets, wise men foretelling the future to the sound of their lyres.

Homer Singing His Iliad at the Gate of Athens

1811

Guillaume Lethière (1760–1832)

Blind musicians are often used in art and literature as a device to stir an emotional reaction. Hope by G. F. Watts, is imagined as a blind figure, crouched over their lyre, plucking forlornly at the strings – an image designed to stir pity and pathos.

Similarly, E. D. Clarke, describing a blind female harper at Aberystwyth, wrote 'with trembling hands... she told us the sad tale of her own distress... deprived of her sight, friendless, and poor, she had wandered from place to place' ('A Blind Harper', Northern Whig, 8th June 1837).

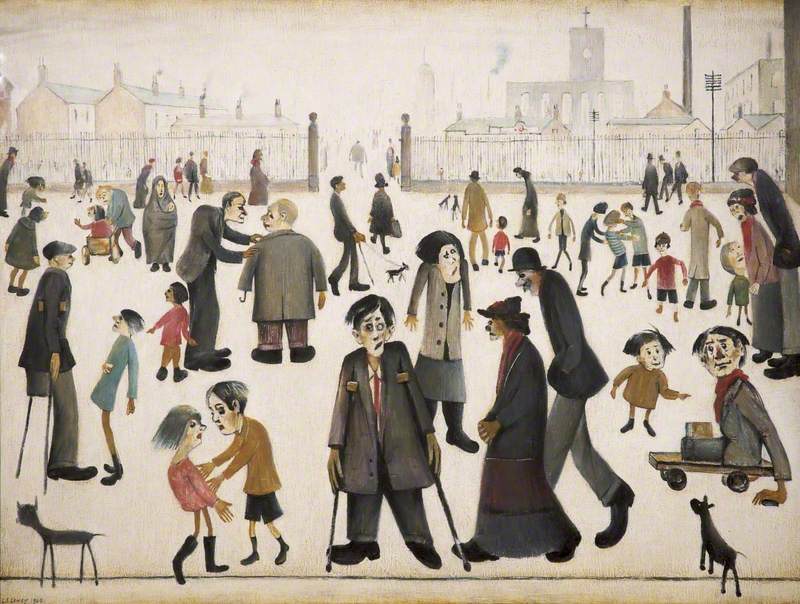

In genre painting, blind musicians are often associated with poverty and loss. They may be shown as beggars, playing on a street corner or in a pub, hoping a kind stranger will toss a few coins their way.

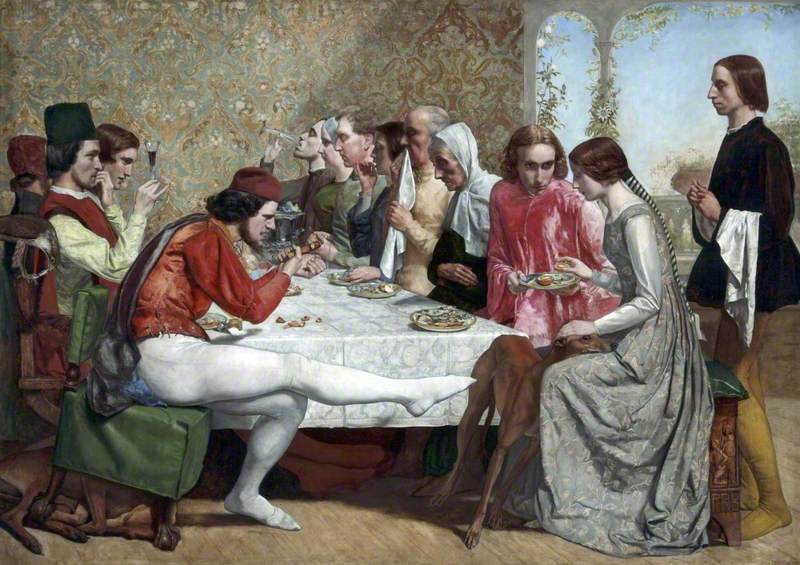

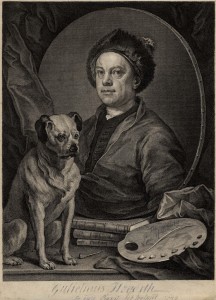

Sometimes they are associated with sin. The blind harper in Hogarth's A Rake's Progress: The Orgy is tucked away in the corner of an inn, playing as the room descends into chaos and sexual debauchery. This links to the harmful idea that disability was a punishment from a god for past sins or transgressions – a concept that held strong for centuries, and is rooted in fear and ignorance about the disabled experience.

These stereotypes – from the blind seer, to the friendless wandering minstrel – tell us little about the lived experience of blind people or the condition of being blind. It reduces the blind person to a trope: a figure that non-blind people project their own emotions and anxieties onto. This has led to harmful ways of thinking about and treating people with disabilities, which continue today.

So what happens when we flip the script? Take John Parry for example. What happens if we consider how his blindness enabled and contributed to his success, rather than being a burden he had to overcome?

There are no known accounts in Parry's own words which describe what being blind meant to him. We don't know how his sight was affected. But we do know it was a lifelong condition that he probably had since birth. In the eighteenth century, many blind children were encouraged to learn to play an instrument as one of the few ways they could later make a living for themselves. So for John Parry, learning to play the harp was probably because of his blindness, not despite it.

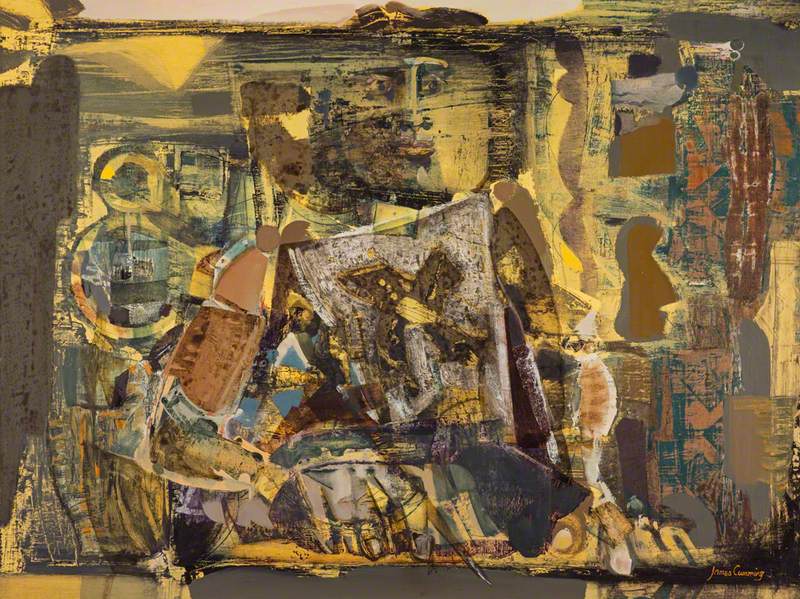

John Parry the Blind Harpist, with an Assistant

1770–1780

William Parry (1742–1791)

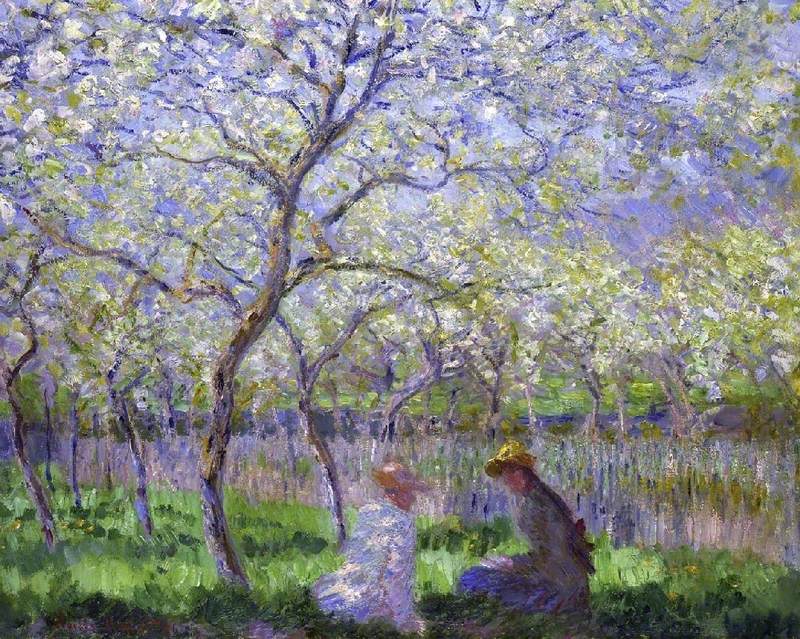

We also know that John Parry had some influence over how his blindness was represented. His son, William, was a portrait artist who painted his father a number of times in the 1770s. These portraits show him as a gentleman, refined and well-dressed – a world apart from the stereotyped images of poor blind harpists common in genre paintings.

Tate's Portrait of John Parry Holding his Harp has more in common with Thomas Hudson's portrait of Handel, which shows him as a distinguished and cultured musician. Handel, too, was blind at this point. In John Parry, the Blind Harpist with an Assistant, Parry is playing Handel's famous coronation anthem, Zadok the Priest – a case of one blind musician paying tribute to another.

As the eighteenth century progressed, there was an increase in doctors and oculists trying to 'cure' people of their blindness, and some of these cases captured public attention – like William Taylor, a young boy from Kent, who became famous after his sight was restored in 1751. Sight restoration procedures were increasingly being advertised in London, and Denbighshire, where John Parry lived and spent most of his time. It is very likely he was aware of these, but there is no record of him ever attempting surgery.

William Taylor, a boy born blind, gazing into a mirror after having his sight restored by surgery

1751, engraving by T. Worlidge

More significantly, John Parry used his blindness to elevate his cultural status, by taking advantage of the association between bards and blindness. He claimed that his popular publications of Welsh folk music were the 'remains of those originally sung by the bards of Wales.' To his contemporaries in the cultural elite, John Parry became a living embodiment of these ancient bards, and his blindness added legitimacy to this claim.

It's important to note that John Parry was the exception and not the rule. He benefited from the support of one of the richest families in Wales, the Williams-Wynns of Wynnstay, and this gave him a level of financial security and a cultural platform that was out of the reach of most blind harpists of the time.

His unique example shows that perhaps the biggest barrier facing blind people at the time was not blindness itself – and that with the right circumstances and support, blindness could be more of a benefit than a burden.

Steph Roberts, Art UK Commissioning Editor – Wales

This content was supported by Welsh Government funding

The original research stems from an Understanding British Portraits network fellowship award 2022/2023, supported by Amgueddfa Cymru. The project sought to use portraits of blind harpists from the Museum's collection to challenge outdated ideas about blindness in museums.

Further reading

Moshe Barasch, Blindness: The History of a Mental Image in Western Thought, Routledge, 2001

Miles Wynn Cato, Parry, published by the author, 2008

Georgina Kleege, More than Meets the Eye, Oxford University Press, 2018

Chris Mounsey, Sight Correction: Vision and Blindness in Eighteenth-Century Britain, University of Virginia Press, 2019

Mark Paterson, Seeing with the Hands: Blindness, Vision, and Touch after Descartes, Edinburgh University Press, 2016

Steph Roberts, The Blind Harpists: Another Look, Celf ar y Cyd, 2023