Posh.

The word can roll off the tongue in art galleries. Synonymous with fine art, the word is loaded not just with class prejudice but also speaks to us of wider sociology at play in the art world. As art holds a mirror to society, so too does it illuminate deeply personal, political or economic expressions of ourselves.

Class is a nebulous term, herding vast swathes of us into categories we may or may not ascribe to socially and economically. We know class exists within British society – indeed arguably it's within the very DNA of our nation. Yet often it's unspoken. Art formed within, acquired during, or made by British history is inherently a product of class systems – consciously or not. How do we articulate conversations on class in art history? And for what purpose?

Grayson Perry is a powerful example of the artist's fascination with exploring class narratives. Crashing into the conversation with bold beauty, Posh Art (1992, in Victoria Art Gallery, Bath) greets us with the classic archetype of the urn, resplendent and consciously reaching for grandeur.

We visually read this as elite, reflective of wealth, upper-class lives – perhaps harking back to the eighteenth-century Grand Tour for young aristocrats. Carved into and adorned with the faces of royalty, we see the one per cent of history set in imagery akin to the ancient past. Look deeper though, and proportions shift. It's not symmetrical, regulated or controlled in its expression. Meaning overlaps, building to the typography that dominates this piece.

It self-proclaims, draws attention to and bellows intent. To be posh, to be within a class system is unavoidable in this work as a theme. As class narratives in our society may be linked to notions of struggle, this artwork arguably positions itself so loudly that we would struggle to avoid the message. It proclaims conversations on class are both real and valid.

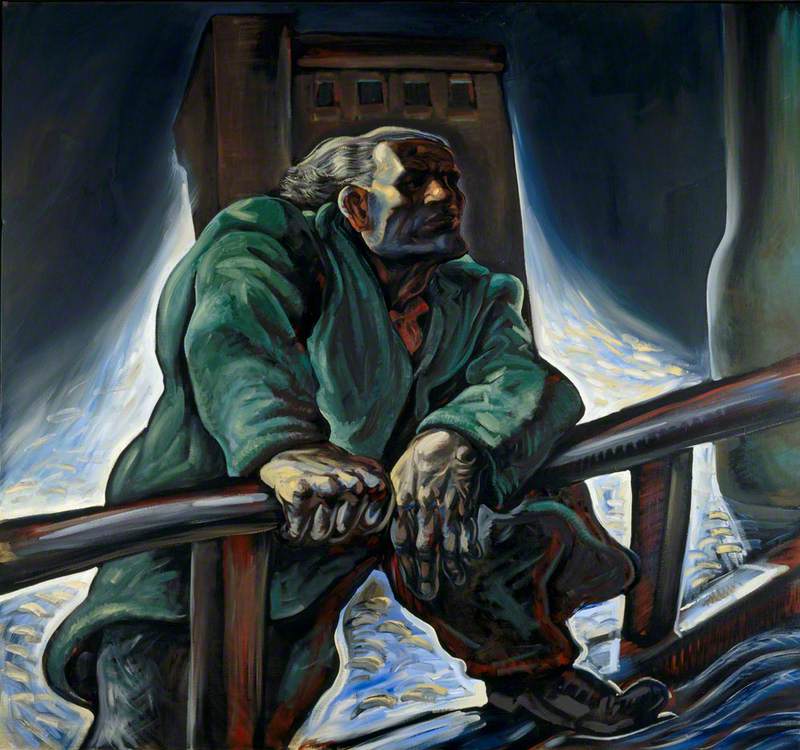

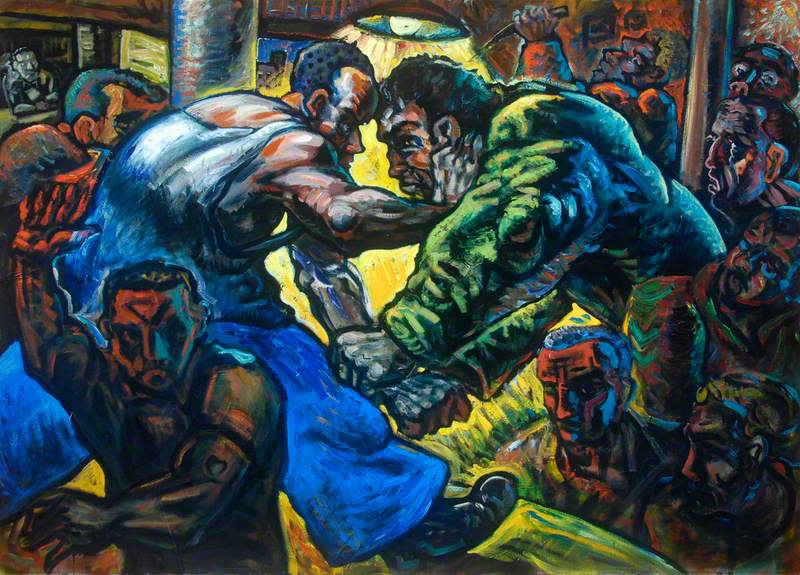

Pair this work with The Heroic Dosser by Peter Howson from 1987 and class identity and language takes on monumental proportions.

The central figure here is based on a real person Howson encountered in an area near homeless hostels in Glasgow. Leaning on the rail, half-hidden in shadow stands our figure to which we literally look up. Dramatic lighting and shading build both power and intensity. It manifests strength, offers visual readings on dignity, yet ultimately denies us the identity of the individual pictured – an everyman in many respects.

Look up 'dosser' in the Oxford English Dictionary and you'll find:

dosser noun (derogatory)

1. a person who sleeps rough: a tramp

2. an idle person

Painful and derogatory language? Or has the artist included it here as a moment of empowerment, advocacy and to draw attention to our figure? Here we see language and imagery combine viscerally to express class identity.

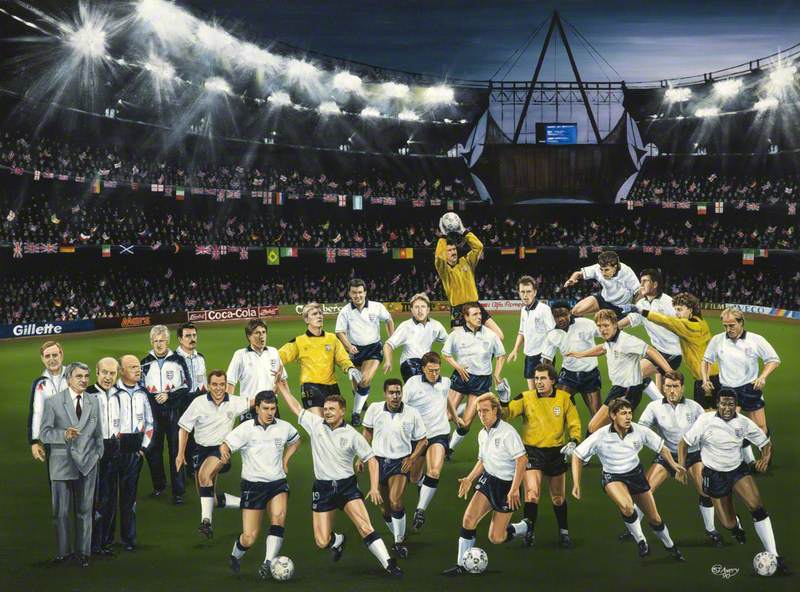

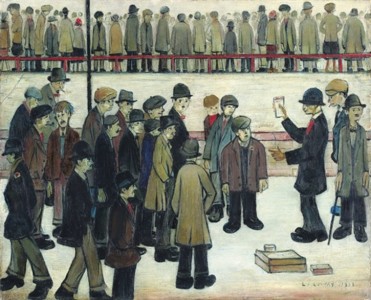

Art can also document class action manifested as a physicality – Marching Out (2001) by George Robson is a beautiful example.

From a mining community himself, Robson worked for the National Union of Mineworkers at their headquarters in Durham for 30 years. After retiring in 1993, he focused on this work and lived experience as an artist, depicting mining communities of North-East England as a central theme of his work. Pictured here we see the Durham Miners Gala, a regional fixture since 1871.

The image carries a powerful weight. It represents not just tradition; but the mobilisation of a working community inexorably linked with trade unionism, industrial action and the violent politics of the 1980s which decimated trades such as mining. Marching Out shows class action manifest, granulated and almost abstracted in monotone to give the impression of energy and emotion, yet it deliberately denies us fine detail.

Class narratives can and do manifest with subtly, though with no less impact or emotion. Take, for instance, A Peasant Boy Leaning on a Sill by Murillo from c.1675–1680.

A Peasant Boy leaning on a Sill

1670-80

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617–1682)

Read for class studies, this piece is searing in terms of objectification. We are greeted with a smiling child, radiant with health. He leans on the stone, allowing the loose-fitting (hand-me-down?) clothing to fall carelessly over the shoulder. It's deliberately charming. A work of incredible talent, idyllic – and deeply flawed in perception.

Consider the child is framed as a peasant, in poverty, of lower class or living on the breadline perhaps. Yet his teeth are pearly and gleaming, his skin radiates health. The ragged clothing is pristine. This, arguably, is not a picture of the trappings of struggle or deprivation – a life of financial insecurity, limited resources, possibly hard physical labour and the effect this has on the body. Would the child have presented like this in real life, or is sanitised editing at play?

Murillo painted for the middle class and those with wealth. Do they want to see a searing reality of poverty, or instead poverty on their terms and within their framework of privilege? Is this work in support of the peasantry, or objectifying their reality for leisure, morality, or perhaps escapism? Seen through this lens, it's deeply uncomfortable to consider the portrayal and purpose of the piece. It's a telling example that when we see class narratives unfold, cases such as this are seen through the perception of privilege, a perception we in turn inherit unchallenged.

Apply this to The Beggar Boy by John Opie and the narrative of the idyllic child living in poverty reminds us that class conversation is part of a whole genre in art.

As the luminous eyes of the child ask us for aid, is this work in support of the child or objectifying the emotion of their socio-economic state? Interesting to consider here is that we know, in the case of Opie, he demonstrated care for the provision of those living in deprivation – opening a school he himself taught at in support of children living in poverty. Does that knowledge enrich our reading of this artwork in terms of class studies?

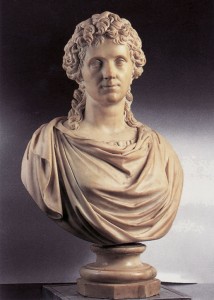

It's important to remember that class narratives are not fixed in art history, but document shifting states. This is especially powerful in consideration of those who step outside of historical societal norms. Mistresses, courtesans, and sex workers, for example, illustrate rapidly shifting identities in class. This portrait of a lady is possibly Margaret 'Peg' Hughes – actress and mistress of Prince Rupert of the Rhine. It is a radiant example of opulence.

This lavish image of (presumably) Peg is codified in class straight away by her appearance. Dishevelled and without visible corsetry or modestly, it aligns with the late seventeenth-century upper-class vogue of drapery signifying social status, not seen in middle- or working-class depictions. Peg herself is noted as one of the first actresses of the English stage as legalised by Charles II.

From perceived lower-class origins and the association of being an 'orange seller' or perhaps sex worker, she rapidly accelerated class distinctions on becoming the mistress of the king's cousin, Prince Rupert of the Rhine. The birth of their child cemented her, for want of a better term, transitory class status. She would never again live a working-class life.

Yet simultaneously she remained the mistress and professionally 'other', as an actor performing a role. Whilst she occupied the visual trappings and lifestyle of the aristocracy, she was never or would never be one of them. Arguably Peg, in stepping out of her origins, became classless. Middle class? Pseudo upper class? No fixed term fully applies.

As in art, society continues to evolve and shift rapidly. Are our perceptions of class rooted in art history? Recent media dialogue offers telling insights into contemporary class narratives and their effect on art. Rapidly shifting economic perception increasingly dictates the nature of how we self-identity in terms of class, competing with perceptions of class as defined by the communities we grew up in and the inherited values within.

As with all art subjects, context is key. Alfred James Munnings explicitly asks us a question in one of his works titled Study of One of Selfridge's Young Ladies, in a Pink Selfridge's Dress, for 'Does the Subject Matter?'.

Study of Miss Patricia Potter, in a Pink Selfridge's Dress, for 'Does the Subject Matter?'

Alfred James Munnings (1878–1959)

The frothy, elegant, dream-like state of the women, pictured in mid-twentieth-century splendour, aches with glamour. Yet it's inescapable she is wearing a Selfridges dress, and her being able to wear that brand, or afford that lifestyle, associates privilege.

Who, then, are the new class identifiers in art collections? Interestingly, the New Stateman suggests, in one of its polls, that according to wealth, premiership footballers are increasingly seen as the new social elite by their status, income and influence. It leads us to wonder: when considering class studies, should look to the gilded masterpieces of historical aristocratic life, by artists such as Van Dyck? Are they still relevant?

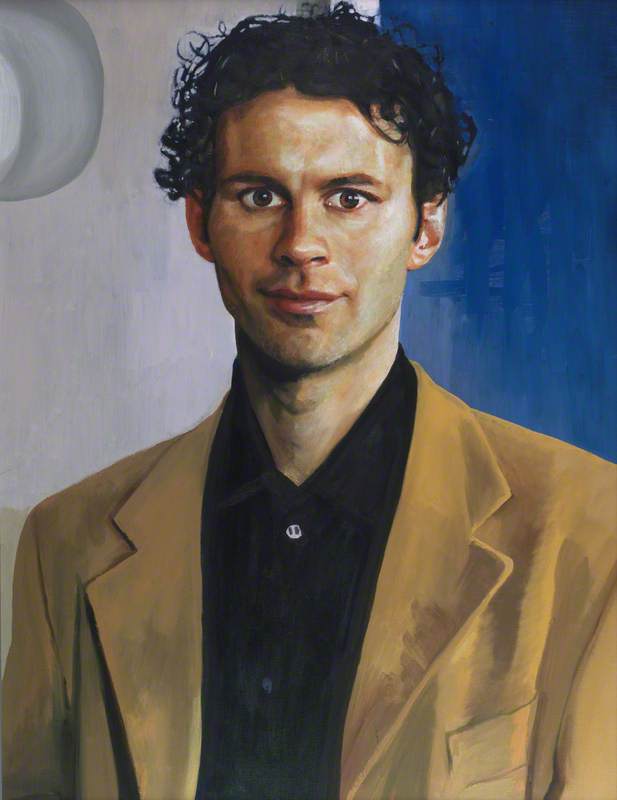

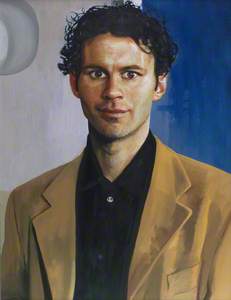

Or perhaps instead, should we look to contemporaries such as Peter Douglas Edwards and his depiction of footballer Ryan Giggs as seen in The National Library of Wales?

Jon Sleigh, freelance arts educator