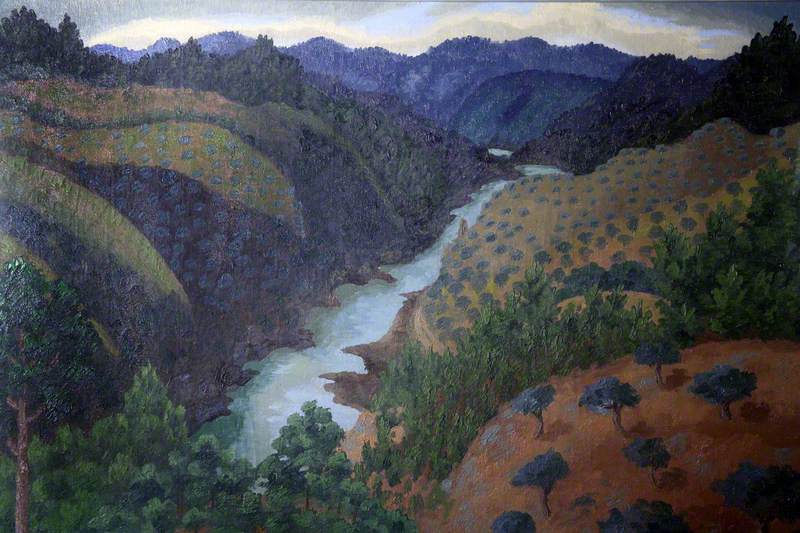

Portugal has always been popular with British tourists. During the military dictatorship (the Estado Novo) of 1933–1974, the British were some of the few Europeans to visit the country regularly. Naturally, this included artists, especially in the mid-century. Through these works, we can see how the modernist eye was turned towards a country which is less familiar in art history than other Mediterranean countries such as France, Italy, Spain and Greece.

The Welsh painter Cedric Morris evidently first visited Portugal as early as 1950. He returned frequently, noting down his observations on the country (as well as Spain) which were published posthumously in 1985. One painting from his trip in 1959 depicts the Marquês de Pombal's eighteenth-century palace at Oeiras, near Lisbon.

By this time, Morris was around 70 years old, and his botanical interests were equally established besides painting (his gravestone is even inscribed 'Artist/Plantsman'). With this dual interest in plants and the visual arts, Morris juxtaposed unruly palm trees with the formal linearity of the European palace. The classical busts in the immediate foreground, like spectators to the scene, reveal that Morris painted the palace from atop the elaborate Cascata dos Poetas (Poets' Waterfall), with its four busts representing Tasso, Homer, Virgil and Camões.

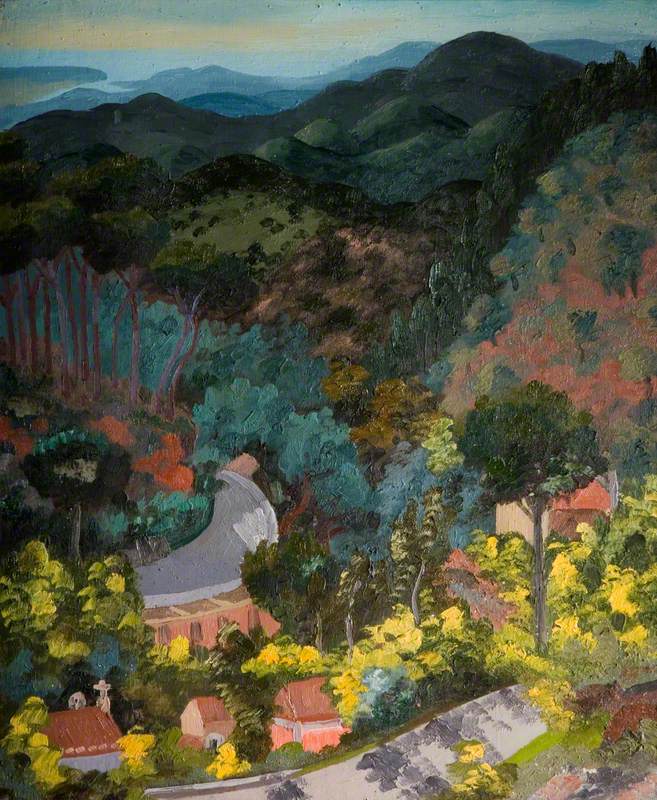

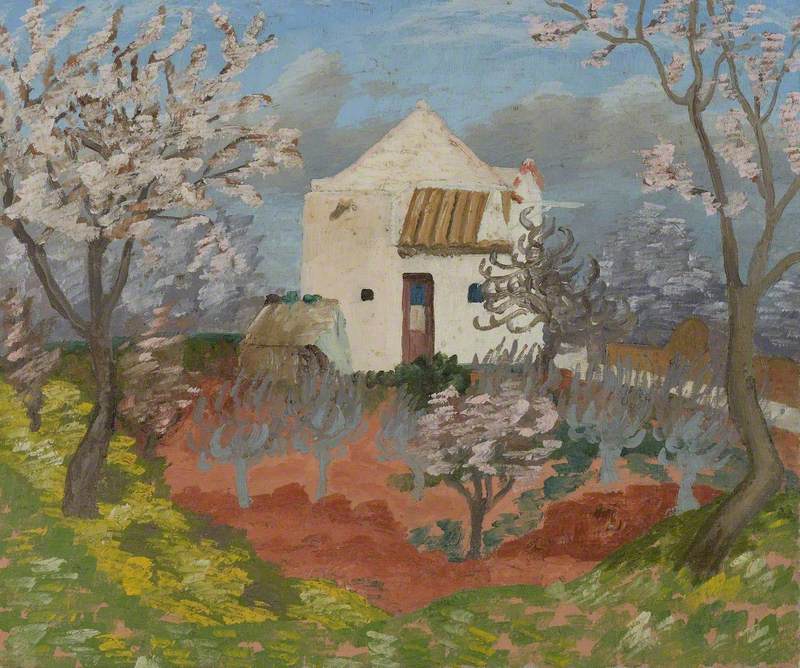

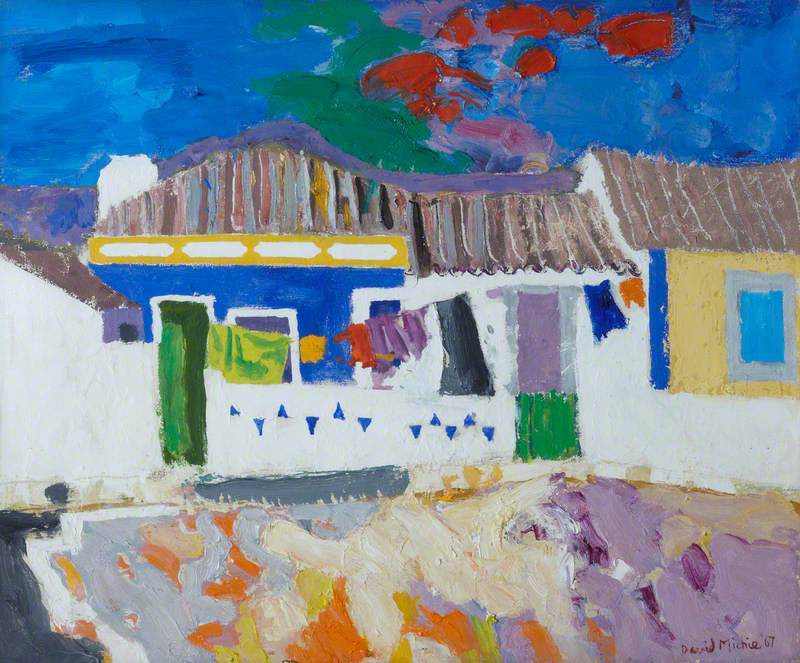

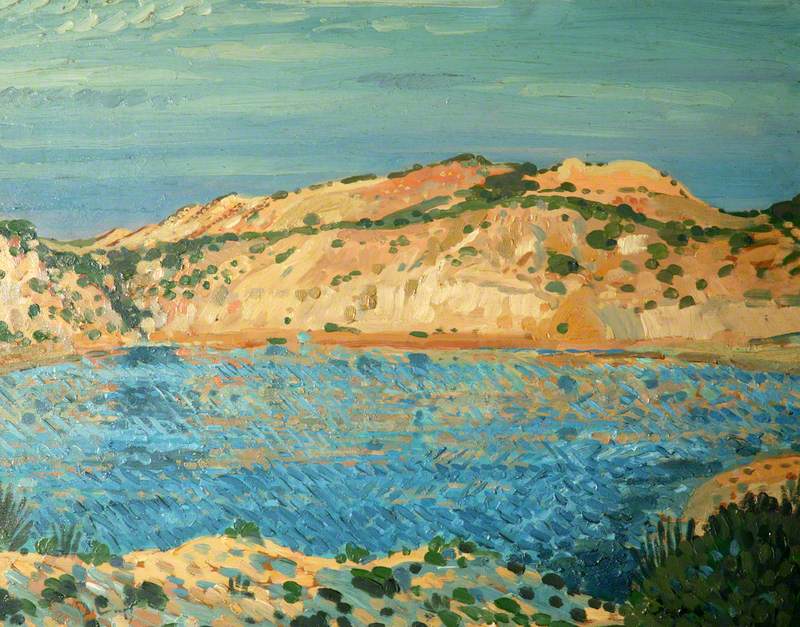

If Morris's painting presents Portugal's austere Baroque buildings, works such as Near Portimão, Algarve shift the focus to its vernacular architecture – a labourer's dwelling, rather than a palace. The combination of whitewashed walls and terracotta roof tiles clearly appealed.

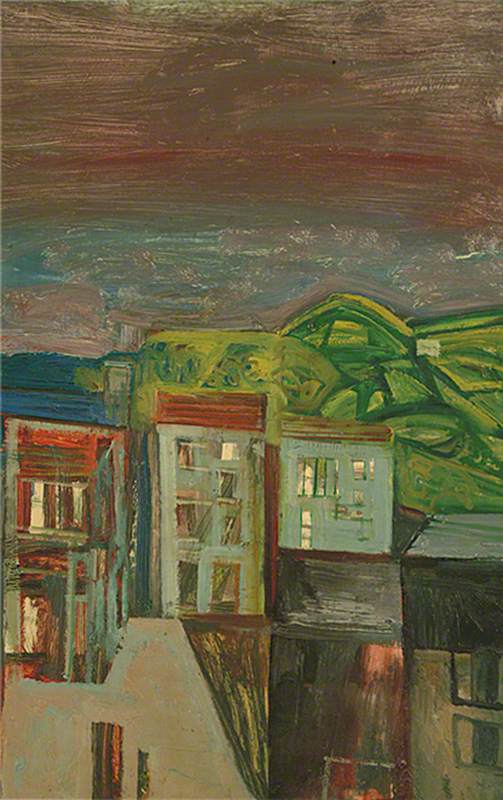

Indeed, Portuguese buildings of all kinds were attractive to other British travellers, and everyday houses appear just as frequently as the opulent churches and monasteries for which the country is famous. The Scottish painter David Michie's vibrant depiction of a row of houses, complete with washing line, calls our attention to similar architectural elements which Morris painted near Portimão in the 1950s.

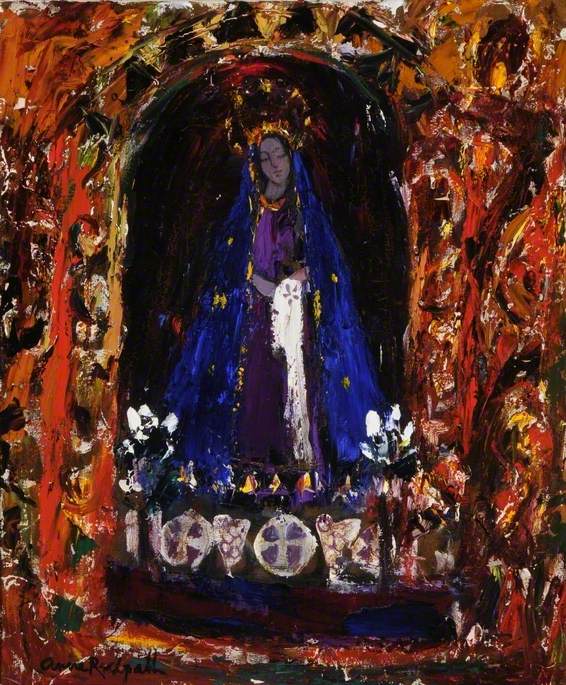

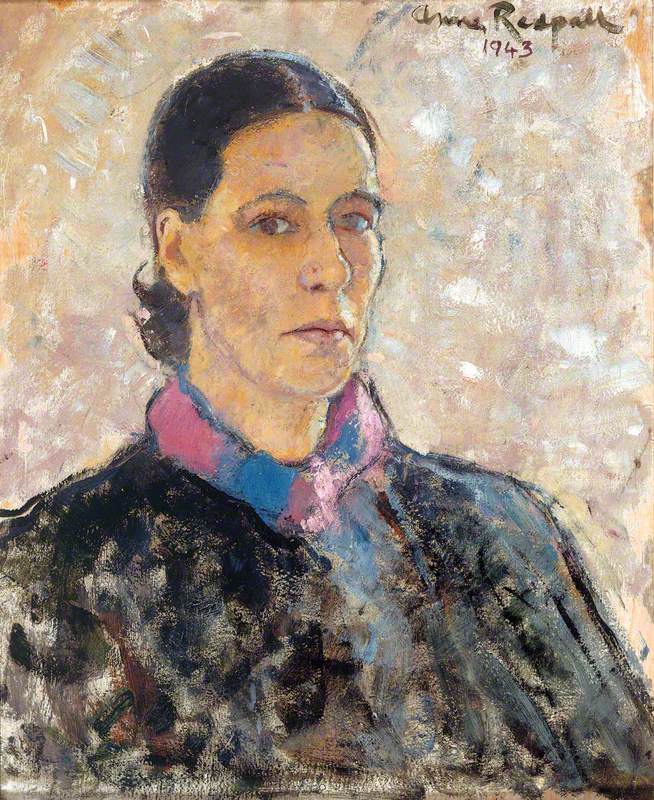

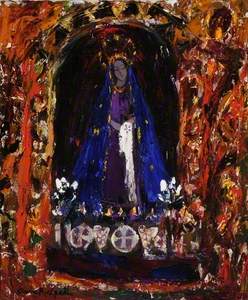

This was painted in 1967, and Michie was following in the footsteps of his mother, Anne Redpath, who first went to Portugal six years earlier. Like Morris, Redpath was well established as a painter by this time, particularly of still lifes. Her extraordinary series of paintings of Portuguese and Spanish church altars includes this one of a Holy Family group, which was first exhibited at the Lefevre Gallery in 1962.

Redpath was raised a Protestant in Scotland, but in the early 1960s she became fascinated with Iberian Catholic imagery. In her Portuguese trompe-l'œil above, it is not immediately clear if we are looking at a painting within a painting, or a painting of a sculpture; it is in fact the latter, as Redpath's picture resembles a specific retable in the church of Santa Maria de Belém (in the Jerónimos Monastery) in Lisbon.

Through a flattening of perspective and intense focus on decoration, Redpath reworks the sculpture into the appearance of a religious icon. These later church paintings mark a significant shift in Redpath's style which relied more on heavy applications of paint and vibrant colour. Before the 1960s, her work rarely contained Christian references – Portugal and Spain therefore inspired a striking new direction in her art.

Redpath's interest in Portuguese visual culture led her to paint this still life of a breakfast table, also in 1962. The Rooster (Galo) of Barcelos, the well-known symbol of Portugal, appears alongside a hand-painted ceramic coffee pot of the kind which is produced in Alcobaça. Redpath died only three years later, in 1965, aged 70.

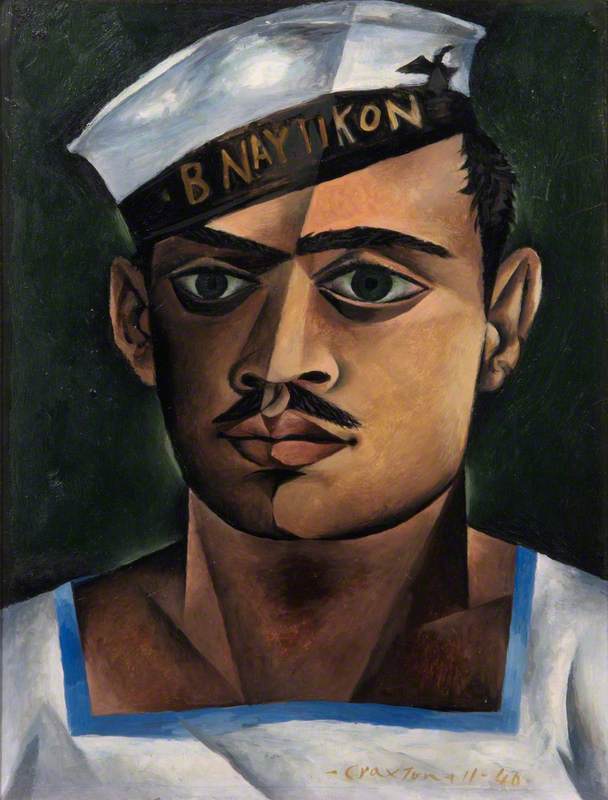

Another Scottish painter who travelled to Portugal was Elizabeth V. Blackadder, in 1966. The trip provided her with material for a large series of paintings such as the one below, which depicts the chapel of Santa Marta in Ericeira, a seaside town. Blackadder later recalled being inspired by the churches' 'strong shapes and colours' and the fishermen's 'colourful costumes' in equal measure.

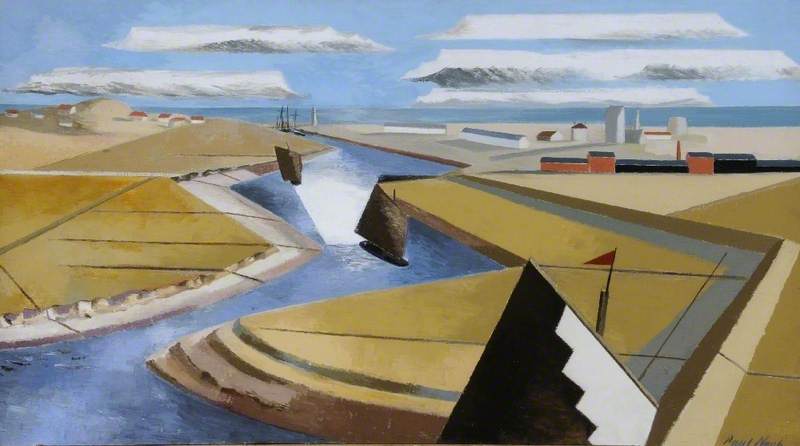

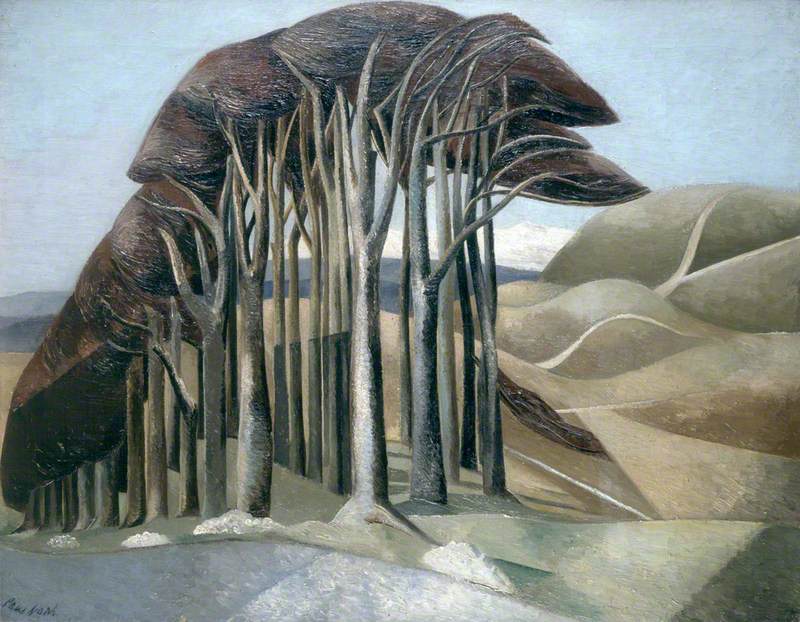

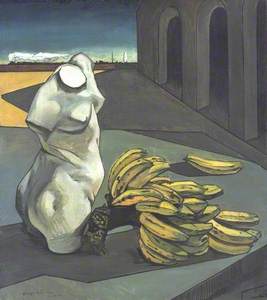

Tristram Hillier, the English surrealist painter and member of the Unit One group led by Paul Nash, first went to Portugal before Morris, Redpath and Blackadder, in the summer of 1947. He had already been to Spain and described the Iberian Peninsula in his autobiography as 'neither European nor Asiatic in character, a land set apart from all others, but one pre-eminently to inspire a painter'.

Portugal provided an immediate new direction for Hillier's work, and he embarked on a series of views of deserted squares enclosed by the country's striking historic architecture.

As art historian Martin Ferguson Smith has shown, this small painting of the church of the Misericordia in Viseu was likely based on a photograph which Hillier acquired in the town in June and July 1947. Although Hillier made some sketches of the church during his visit, Smith concludes that he 'relied on photographs to a greater extent than usual' on this occasion, as the church's architecture was particularly challenging to paint.

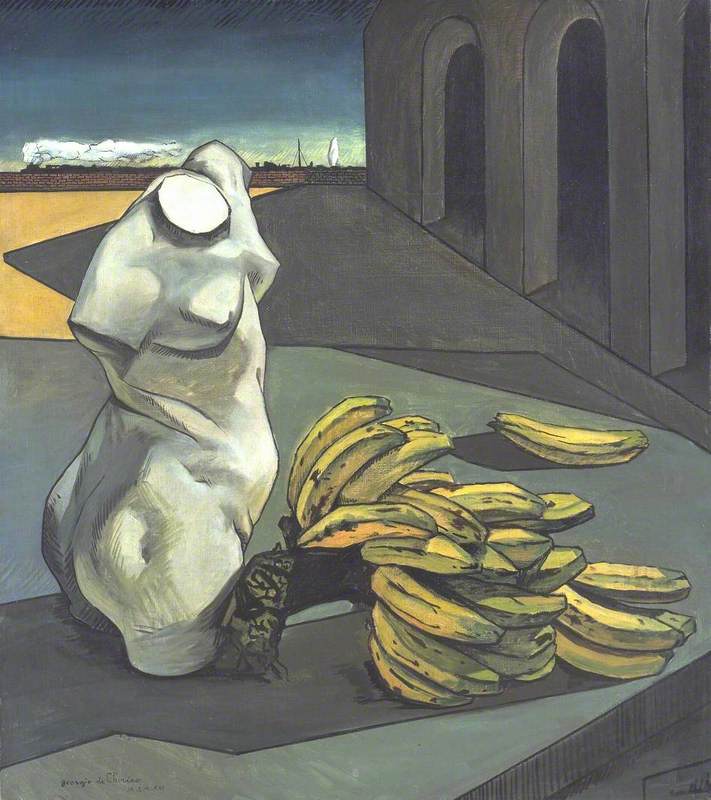

Also in 1947, Hillier completed the above painting of Viseu; the church of the Misericordia, now seen from behind, is visible on the left of the picture. The resemblance to Giorgio de Chirico's work is clear, with its arrangement of geometric architectural forms around a vacant public square.

An exhibition of Hillier's Portuguese pictures was held at Arthur Tooth & Sons in London in the spring of 1948. Like Morris, Hillier returned to Portugal many times, regularly passing the summer months in the countryside near Portalegre in the 1960s.

Another holidaymaker in Portugal in the 1960s was Edward Bawden, resulting in several linocuts which were printed especially for the Motif art journal in 1962. His interest in the country's ornate Baroque architecture is expressed in a print depicting the statuary in the Jardim do Paço in the city of Castelo Branco. The garden's ornamental hedges are presented as an abstracted mosaic around the figures.

To conclude, here is a curious little painting by Duncan Grant, which shows the unassuming entrance to a building – perhaps a train station – in Lisbon.

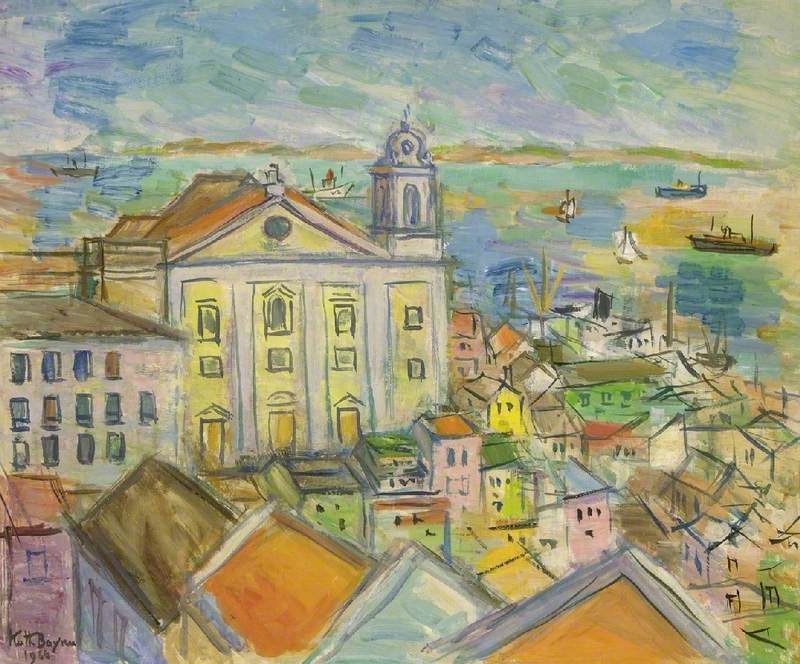

It was painted during Grant's holiday to Portugal in 1972, in company with the painter Keith Baynes (below) and the critic and historian Richard Shone. According to art historian Frances Spalding, Grant, who by then was in his late 80s, also produced drawings and pastels during his holiday.

British artists' fascination with Portugal during this period is relatively underexplored, although, of course, the country itself remains enduringly popular with British tourists generally.

Robert Wilkes, independent art historian based in São Paulo

This content was supported by Jerwood Foundation

Further reading

Eva Maria Marques Milheiro, 'A revolução militar portuguesa de 1974 e suas implicações no turismo nacional', in Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, vol. 15, no. 2, 2017

Motif: A Journal of the Visual Arts, no. 9, 1962

Richard Morphet, Cedric Morris, Tate Publishing, 1984

Martin Ferguson Smith, 'The first visit of Tristram Hillier (1905–1983) to Portugal', in The British Art Journal, vol. 20, no. 1, 2019

Frances Spalding, Duncan Grant: A Biography, Pimlico, 1998

Christopher Woodward, 'Cedric Morris' Winter Journeys', Garden Museum, 2017