One year ago, in March 2020, a lost portrait of Millicent Fawcett was discovered at Royal Holloway, University of London. Today we think of Fawcett as a suffragist and campaigner, and president of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). But she was also a published author and lecturer on the subject of higher education for women. In 1899, Fawcett received one of the first honorary doctorates awarded to a woman, a moment of great celebration for the suffrage and women's education movements.

Millicent Fawcett (1847–1929)

Millicent Garrett Fawcett (1847–1929)

c.1898

Theodore Blake Wirgman (1848–1925)

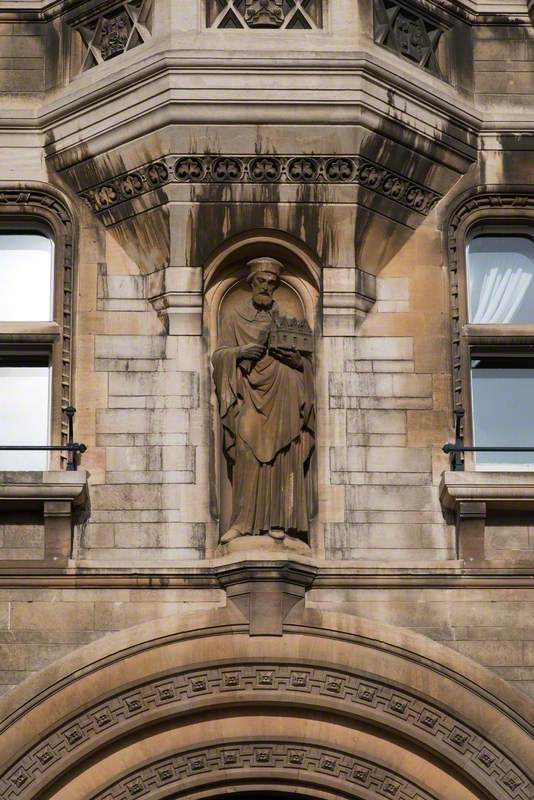

Fawcett is portrayed as a studious, simply dressed young woman, who looks up as if interrupted in her reading. In the gloomy background over her right shoulder, a pile of books emphasises Fawcett's status as a scholar, drawing on traditions that go back to Renaissance depictions of studious thinkers like Saint Jerome. British-Swedish artist Theodore Blake Wirgman had used these tropes before, in earlier portraits of male sitters. Yet in a portrait of Fawcett, a woman and a known campaigner for women's rights, such visual traditions would have seemed rather more contentious.

With the foundation of colleges for women's higher education, such as Bedford College in 1849 and Royal Holloway College in 1886, artists were increasingly called upon to paint women who were educated and involved in the education of others. New colleges wanted portraits of their principals, intended as symbols of institutional continuity and collective identity at a time when women's higher education was still considered controversial. These paintings strike a delicate balance between conservatism and innovation, as painters found new ways to paint 'thinking women': professional women employed as leaders in a new sphere, who wished to be painted as such.

Matilda Ellen Bishop (1842–1913)

Miss Matilda Ellen Bishop

1897

James Jebusa Shannon (1862–1923)

Colleges commissioned portraits from the leading society portrait painters of the day, such as James Jebusa Shannon. He became rather a favourite among women's colleges like Newnham College and Lady Margaret Hall, for whom he painted a number of 'thinking women'. In 1896, Shannon painted Matilda Ellen Bishop, the first principal of Royal Holloway College. Bishop had not had a university education herself. She was employed to manage administration and guide the students' pastoral care. Her elegant tea-gown, with its large puffed sleeves and frothy lace, is presented with the feminine flounce of one of Shannon's society ladies, captured with his loose, flamboyant brushwork.

Shannon was a founder member of the New English Art Club, a group interested in the innovations of contemporary artists in France. To prospective students and their parents, Bishop's portrait would have been recognisably fashionable in its French aesthetic, but also undeniably unthreatening. Her profession is deliberately downplayed to emphasise her ladylike respectability.

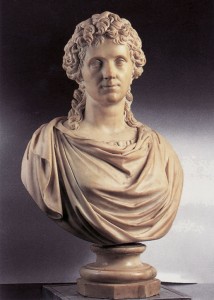

Emily Penrose (1858–1942)

Dame Emily Penrose (1858–1942)

1907

Philip Alexius de László (1869–1937)

The opposite can be said for Philip de László's portrait of Bishop's successor Emily Penrose, who moved from the principalship of Bedford College to Royal Holloway in 1898. This portrait was commissioned in 1907, when Penrose left the college to become the principal of Somerville College, Oxford, where she had studied Classics as an undergraduate. De László had recently moved to England, where he became the most sought-after portrait painter of his day, but he probably received this commission from Royal Holloway thanks to his wife's cousin, Elizabeth Maude Guinness, who was the vice principal at the college.

De László presents Penrose as an educational visionary, gazing into the distance in the manner of a classical muse or allegorical figure. The sweep of her academic hood across her body evokes a Roman senator's sash or the drapery of a neoclassical portrait bust, an appropriate allusion for Penrose as a classicist, which had also been used in eighteenth-century portraits of the Bluestockings Society. Like Shannon, De László became rather a favourite among the women's colleges, and he went on to re-use this sartorial device in later paintings of pioneering professional women wearing academic dress, such as Bertha Philpotts, Helen Gwynne-Vaughan and Dr A. Maude Royden.

Dr A. Maude Royden (1875–1956)

1932

Philip Alexius de László (1869–1937)

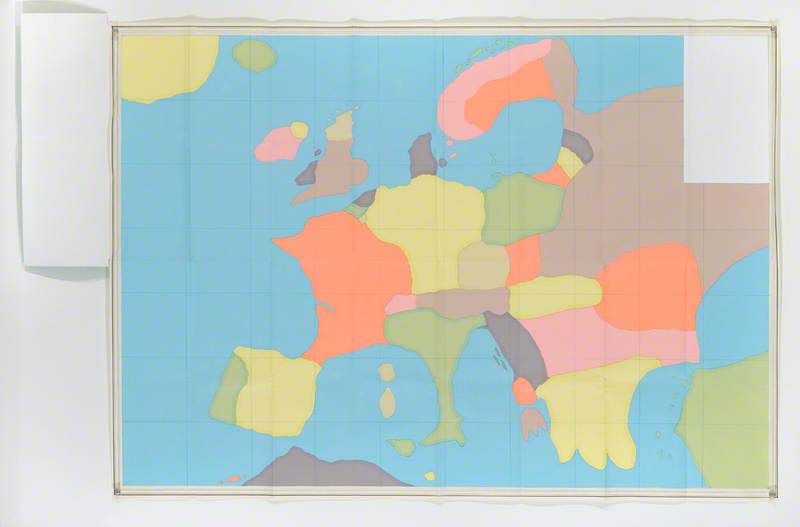

Emily Penrose was one of the first women's college leaders to have studied at university herself, and these portraits of women wearing academic dress were more controversial then than they might appear now. While some universities, including the University of London, had allowed women to receive degrees from 1878, others, Oxford and Cambridge among them, deferred until after 1920. Women like Penrose were not permitted to graduate or to wear the academic gowns of their alma mater. Many in this generation of women instead received their degrees from Trinity College Dublin, which briefly offered degrees to women who had studied at Oxbridge. De László, who liked to paint his sitters wearing the garb of their rank, painted Penrose wearing the distinctive black gown and blue-lined hood bestowed upon the so-called 'steamboat ladies', who travelled to Dublin to receive their degrees.

Henrietta Jex-Blake, Principal (1909–1921)

1921

Philip Alexius de László (1869–1937)

Francis Helps' portrait of Penrose and De Laszlo's portrait of Lady Margaret Hall principal Henrietta Jex-Blake commemorate the distinctive red silks they received with their honorary Master of Arts degrees in October 1920, when these two pioneers finally graduated alongside the first cohort of female graduates.

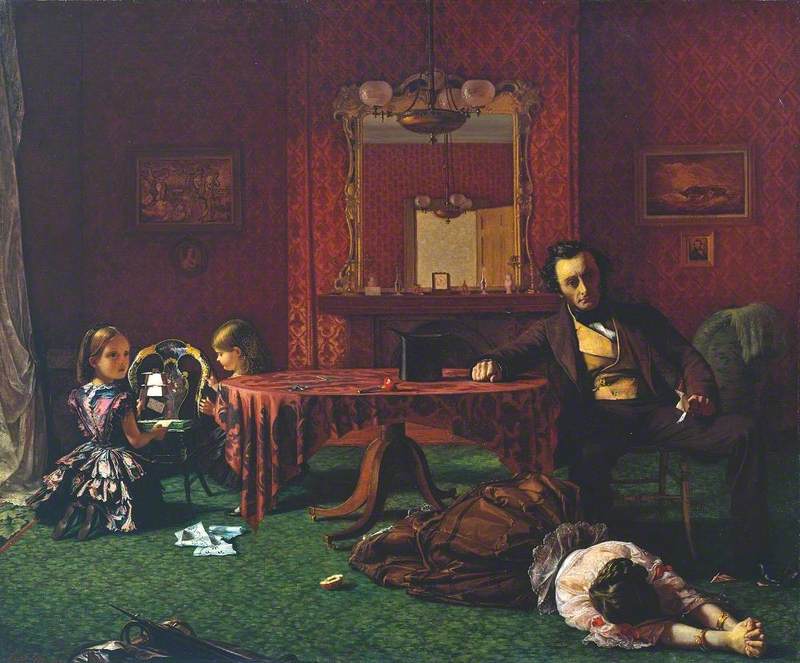

Ellen Charlotte Higgins (1871–1951)

By 1925, when William Orpen accepted a commission to paint the longest-serving principal of Royal Holloway, women's higher education was no longer controversial. Indeed, Royal Holloway was perceived as rather old-fashioned in its methods, as was Ellen Charlotte Higgins herself. In some comic verses written on the occasion of her retirement, another staff member joked that this 'Scottish Chief of manly mien' would never give up the long skirts, shirt and tie that had been fashionable in her student days. But this costume worn under her academic hood and gown, together with her imposing stance and direct gaze, suggests the gravitas of a military commander, and Orpen certainly draws on the conventions for painting uniformed leaders. This standing pose is rather unusual among portraits by Orpen, who was famously short and preferred to paint his sitters seated. It seems likely that Higgins requested this feature herself, probably thinking of the painting's eventual position on a wall beside De László's portrait of her statuesquely standing predecessor Penrose.

Margaret Janson Tuke (1862–1947)

Dame Margaret Janson Tuke (1862–1947)

1934

Francis Dodd (1874–1949)

Personal preference was a decisive factor in the planning and execution of Francis Dodd's portrait of Margaret Janson Tuke, principal of Bedford College. Painted on the occasion of her retirement from the college, this was Tuke's second portrait. The first, a three-quarter-length portrait by Reginald Grenville Eves, in which Tuke wears the distinctive academic gown and hood of the 'steamboat ladies', had not been considered a successful likeness of the sitter, and Dodd's portrait was intended to redress this.

Dame Margaret Janson Tuke (1862–1947)

1914–1915

Reginald Grenville Eves (1876–1941)

Dodd draws on conventions used in Renaissance painting, particularly the work of Giovanni Bellini and Lorenzo Lotto, in his inclusion of the fictive parapet, trompe l'oeil letter with Dodd's signature and the green curtain. The portrait is even painted on panel and framed in an eighteenth-century Italian frame. This was all very appropriate for a portrait of Tuke, a linguist specialising in Italian who would have understood Dodd's playful pastiche of Venetian Renaissance painting. Unfortunately, this Italianate portrait did not please the subscribers of Bedford College, who were again divided as to the veracity of its likeness to Tuke herself. Nonetheless, the portrait demonstrates that by the 1930s 'thinking women' no longer needed their academic gowns as proof of their achievements.

You can find out more about the lives of these extraordinary women and their portraits in the Art UK Curation and recent book Modern Portraits for Modern Women: Principals and Pioneers in the Royal Holloway and Bedford New College Art Collection.

Imogen Tedbury, art historian, curator and author of Modern Portraits for Modern Women